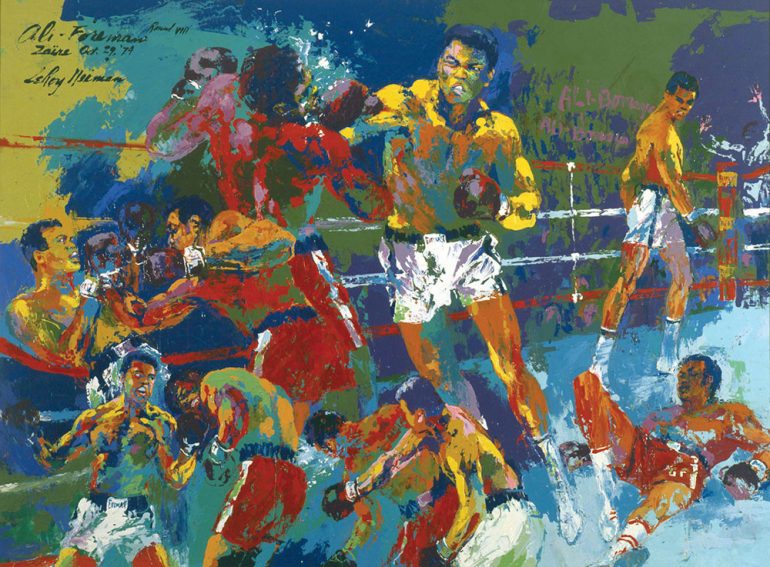

“Rumble in the Jungle” proved to many Ali was greatest of all time

Five years ago today, Muhammad Ali died in Scottsdale, Ariz. at age 74 following a respiratory illness complicated by his decades-long battle with Parkinson’s. The tributes from around the world were voluminous and heartfelt, and the public memorial service staged on June 10 in Louisville, Ky. was watched by an estimated 1 billion people. Ali’s impact on his chosen sport is everlasting, and in honor of his legacy, RingTV.com will present the second of two excerpts from “Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers” written by CompuBox founder and president Bob Canobbio and RingTV.com’s own Lee Groves.

Muhammad Ali’s boxing life is often divided into two parts — the whippet-quick and balletic athlete before the exile, and the wizened veteran of the 1970s who used his imagination (and sometimes friendly judging) to defeat younger men. There is no finer example of Ali’s creativity than his October 30, 1974 “Rumble in the Jungle” against the fearsome George Foreman — a younger, bigger, stronger version of Sonny Liston who had dismissed Ali’s only two conquerors Joe Frazier and Ken Norton with almost ridiculous ease. But Ali’s special brand of magic proved too much for “Big George,” and with his eighth-round TKO victory, Ali’s quest to regain what had been taken from him was now complete.

“Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers” may be purchased on Amazon.com.

***

When Ali emerged from an exile that lasted a little more than 43 months, more than a few believed the 28-year-old would quickly reclaim the throne that had been his during the prime years of his athletic life. That all changed March 8, 1971 when Joe Frazier, the man who seized the crown in Ali’s absence, used his powerful hooks and gargantuan will to win their one-of-a-kind showdown at Madison Square Garden.

That defeat forced Ali to continue what would become a seven-year odyssey to regain the undisputed heavyweight title. But even for a man accustomed to producing sporting magic, Ali couldn’t have fathomed a more theatrical end to his championship chase: Fighting in the heart of central Africa against one of history’s most dangerous punchers in champion George Foreman, Ali reacquired the title — by knockout — with the most extraordinary example of strategic improvisation ever produced inside a boxing ring, a tactic Ali later dubbed the “Rope-a Dope.” The sight of referee Zack Clayton waving off the fight with just two seconds remaining in round eight unleashed a tidal wave of joy that instantly enveloped the globe. The deafening cheers and arm-waving celebrations of the 62,000 souls that jammed into Stade du 20 Mai in Kinshasa, Zaire reflected similar unseen displays at dozens of closed-circuit outlets worldwide. In that moment, because of the weight of his feat and the magnitude of the prize he had just regained, Muhammad Ali the athlete was transformed into Muhammad Ali the icon.

Thanks in part to the machinations of a frizzy-haired ex-con named Don King, Foreman versus Ali was instantly changed from dream fight to reality. Even before financing was secured for the fight, King convinced Foreman and Ali to sign on the dotted line, after which the funds were guaranteed through four entities: Video Techniques, Panama’s Risnella Investment, the British-based Hemdale Film Corporation and Zaire’s dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, who wanted to use the fight to vault his nation into the financial mainstream. (1)

Both fighters were promised a record $5 million purse, twice the amount Ali and Frazier each made four years earlier, but, according to biographer Thomas Hauser, Ali received $5.45 million. (2)

For Ali, the Foreman match must have been a case of deja vu, for while his antagonists were different individuals, they presented a similar set of obstacles. At the same time, however, Ali was forced to address several changes in his own ability level.

In the waning days of his life as Cassius Marcellus Clay, Ali won his first heavyweight championship from Charles “Sonny” Liston, who, coming in, was regarded by many as the most fearsome force the division had ever seen. Against Foreman, however, Ali faced an even more daunting physical and chronological challenge.

The 22-year-old Clay was 11 years younger than Liston and was light years ahead of the champion in terms of hand and foot speed, but against Foreman the 32-year-old Ali was seven years older and was noticeably slower than the version that dethroned “The Big Ugly Bear.” At 6-foot-3 1/2-inches, Foreman stood three inches taller than Liston and sported a more powerful physique. While Liston operated behind an underrated jab, Foreman was a search-and-destroy volume puncher that crushed most opponents in short order. Going into the Ali fight, Foreman’s record was 40-0 and of his 37 knockouts, 21 occurred within the first two rounds — including his last seven fights. Among those seven victims were Frazier and Norton, the only two men to defeat Ali. Not only did Foreman beat them, he pulverized them; he floored Frazier six times and Norton three times before finishing them off in a combined 10 minutes 26 seconds of ring time. Worse yet for Ali, most of their falls were of the spectacular, highlight reel variety. Many Ali fans feared the same fate for their hero.

Foreman was installed as a relatively narrow 3-to-1 favorite but the general sentiment at the time placed even greater odds against Ali. The following quote by the New York Times’ Dave Anderson reflected that conventional wisdom:

“George Foreman might be the heaviest puncher in the history of the heavyweight division. For a few rounds, Ali might be able to escape Foreman’s sledgehammer strength, but not for 15 rounds. Sooner or later, the champion will land one of his sledgehammer punches, and for the first time in his career, Muhammad Ali will be counted out. That could happen in the first round.” (3)

In honor of his mentor Liston, with whom Foreman sparred occasionally, the intrinsically amiable Texan amplified his frightful in-ring performances by projecting a brooding, intimidating persona. He often wore a sneer while giving brief, violence-laden answers to reporters’ questions.

“My opponents don’t worry about losing,” Foreman said. “They worry about getting hurt.” (4)

In his autobiography “By George,” Foreman revealed he contemplated killing an opponent to answer all questions about his worth as a fighter.

“Having demolished Joe Frazier, I didn’t expect to hear doubts about my skill. But there they were. ‘George fought a tomato can’ some people said after the Joe Roman fight. What’s he so scared of?’ I realized such comments were motivated by my growing reputation as the champ you loved to hate. But I couldn’t ignore them. In too many ways I was still the kid from Fifth Ward, fighting to be king of the jungle. I intended to convince every last doubter. ‘I’m going to kill one of these fools,’ I decided. ‘Then everyone’ll shut up.’ The ‘fool’ I chose was Ken Norton.” (5)

The neck-wrenching uppercuts that flattened Norton were a scary sight and after the fight he looked down at Ali, who was doing color commentary for ABC, and said, “I’m going to kill you.” (6) Foreman saw fear in Ali’s eyes that night but the former champ sure didn’t act like it as he proceeded to launch a full-frontal verbal and psychological assault that harkened back to his first fights against Liston and Frazier.

His multi-pronged attack began by ingratiating himself with the local populace through frequent public workouts, humor-filled press conferences and removing all walls between himself and his admirers. Ali repeatedly said that the Zairian people were “my people” and held up their country as a positive example of black leadership. After learning the Lingala word for “kill him” — “bomaye” — he made the “Ali, bomaye” chant a staple of his public appearances.

Another part of the master plan was to dub Foreman “The Mummy” for his heavy-legged stalking and his slow, easily countered punches.

“George telegraphs his punches,” Ali said. “Look out, here comes the left. Whomp! Here comes the right. Whomp! Get ready, here comes another left. Whomp! I’m not scared of George. George ain’t all that tough.” (7)

Foreman wasn’t without his supporters but they were dwarfed by those who threw their full-throated support to Ali. Foreman virtually ceded Ali the “home crowd” advantage by staying in isolation most of the time, and during the rare times he ventured out he was accompanied by guard dogs. Although Foreman long had an affinity for the German Shepherd breed, to the locals it reminded them of the unpleasant days of Belgian colonial rule. (8)

While Foreman dealt with being made into public enemy number one, other parts of the promotion struggled to establish a solid foothold. A fight poster declaring the fight to be “from the slave ship to the championship” had to be replaced following a public outcry and the first set of tickets had to be shipped back and reprinted because Mobutu’s name was misspelled. (9) But those snafus paled in comparison to what happened down the homestretch.

The fight originally was to begin at 3 a.m. September 25 to ensure live prime-time coverage in the U.S. but eight days out the fight was postponed after a stray elbow from sparring partner Bill McMurray sliced open the area above Foreman’s right eye. The fight was rescheduled for 4 a.m. October 30 and both Ali and Foreman remained in Zaire for the duration. (10) While Foreman sulked, Ali took full advantage of the situation by ramping up his already robust PR campaign while also drawing spiritual strength from his African surroundings.

The surroundings inside the soccer stadium hosting the bout spawned a new crisis just hours before the fight was to begin. Ali’s chief second Angelo Dundee and public relations guru Bobby Goodman stopped by the stadium to check out the ring. What they saw horrified them: One side of the ring had sunk into the muddy pitch, the foam rubber padding had become mushy because of the severe heat and humidity and the ropes — which were made for a 24-foot square ring instead of the 20-footer they had — sagged toward the floor.

Seeing this, the two future Hall of Famers became part of an impromptu ring maintenance crew. They placed concrete slabs under the corner posts to balance the ring and placed resin on the canvas to deal with the new surface’s slipperiness.

“(To fix the ropes) we took off the clamps, pulled the ropes through the turnbuckles, lined everything up, and cut off the slack,” Goodman told Hauser. “We took about a foot out of each rope and retightened the turnbuckles by hand so they could be tightened more just before the fight. Angelo even told the ring chief that, right before the first bout, he should tighten the ropes by turning the turnbuckle. And then, before the main event, they were supposed to tighten them again. That never happened. They just didn’t do it, so by the time Ali got in the ring the ropes were slack, but there was nothing underhanded in what Angelo did. In fact, Dick Sadler and Archie Moore, who were Foreman’s corner men, saw us that afternoon in the ring. Angelo and I were sweating our butts off, cutting the ropes with a double-edged razor blade because nobody could find a knife. We were pulling them through, taping up the ends. And we said, ‘come on! You know, you guys can help.’ But it was hot and they wouldn’t give us a hand.” (11)

With massive rain clouds hovering over the stadium and dozens of traditional African dancers and percussionists adding to the exotic atmosphere, Ali, as the challenger, was the first to emerge from his dressing room. Even though he flashed a small smile from time to time as he navigated the lengthy soccer pitch he looked focused and ready to fight. Team Foreman chose to make Ali wait inside the ring for an uncomfortably long time, but once the champion came out he and his team jogged toward the ring. Both appeared in perfect condition as Ali scaled 216.7 pounds to Foreman’s 220, 30 pounds lighter than what the defending champion scaled in August. (12)

Following the introductions, each man tried to secure one final psychological advantage: Ali by chattering, Foreman by fixing a stony stare. That battle went down as a draw but the one that followed had a decisive winner.

Ali’s original plan was to move constantly, use his quicker hands to beat Foreman to the punch and extend the fight to exploit Foreman’s questionable stamina. Although his stick-and-move tactics won Ali the opening round, his surroundings and his opponent’s tactics demanded a dramatic shift in strategy.

First, Ali realized the heavily padded canvas would deaden his legs long before the end of the scheduled 15-rounder. Second, if the canvas didn’t empty his gas tank the oppressive heat and humidity — both of which were in the 80s even at 4 a.m. — would. Finally, Foreman proved himself quite adept at cutting off the ring, which meant Ali would expend more energy getting to his escape routes than Foreman would by blocking them. Even worse for Ali: The available space inside the ropes was 19 feet square instead of the usual 20. (13)

Foreman’s first-round effectiveness was reflected in the statistics, which saw Foreman land 17 of 43 punches, including 14 of 35 power shots. Ali, for his part, attempted only 30 punches, landing nine, and his jab was limited to just 3 of 13.

To Ali, every equation added up to disaster. Thus, Ali’s fertile mind produced an antidote that, on the surface, was suicidal but in practice was a stroke of genius.

One minute into round two, Ali retreated to the ropes and appeared to give Foreman exactly what he wanted — a stationary target ready to absorb massive punishment. Eager to shut Ali’s mouth as well as prove his manhood to all the world, Foreman tore into Ali with ferocious body shots and huge swings aimed at Ali’s head. For Ali’s corner it was their worst nightmare come true and writer George Plimpton, who was seated at ringside, thought he was witnessing a fix. (14)

The stats, however, told a different story. Yes, Foreman still out-landed Ali 18-14 in the second and 24-20 in the third, but Ali was striking the champion with stunning regularity. His sprightly counters enabled Ali to land 41% of his total punches in the second (including 46% of his jabs, 10 of 22) and 57% across the board in the third (20 of 35 overall, 12 of 21 jabs and 8 of 14 power punches). Meanwhile, Foreman, thrilled at the prospect of a stationary Ali, shrugged off the challenger’s blows and kept on firing. Given that Foreman had landed 38% of his power punches in the second and 52% of them in the third, he had good reason to feel that way.

For all of Foreman’s early numerical success, Ali had created a tempting mirage and Foreman, thirsting for another career-defining knockout victory, willingly fell under its spell. No longer the dancing master of the late-1960s, Ali compensated for the ravages of age by learning how to fight off the ropes during numerous sparring sessions. There, he learned how to pick off blows with his arms, pivot his torso ever so slightly to minimize the impact of body blows and formulate the proper counters for the punches coming at him. Those sparring sessions enabled Ali to create an entirely new map from which to operate and he had the confidence — and the bravery — to apply that map during one of the most critical moments of his fighting life.

In retrospect the components of the “Rope-a-Dope” addressed every problem Ali encountered in round one. By staying stationary Ali preserved enough strength in his legs to move only when necessary while simultaneously prompting an overanxious Foreman to drain his gas tank. Second, the looser-than-normal ropes enabled Ali to lean back far enough to remove his head from the plane of Foreman’s bombs. Third, Ali’s energy-saving maneuvers neutralized the effects of the weather for him while exacerbating them for Foreman. Finally, the tactic allowed Ali to exploit Foreman’s predatory mindset, which knew nothing about pacing oneself for a 15-round fight, while Ali, a veteran of long fights, could take his time and assess his options.

“Starting in the second round, I gave George what he thought he wanted,” Ali recalled. “And he hit hard. A couple of times he shook me bad, especially with the right hand. But I blocked and dodged most of what he threw, and each round his punches got slower and hurt less when they landed. I was on the ropes, but he was trapped because attacking was all he knew how to do. By round six, I knew he was tired. His punches weren’t as hard as before.” (15)

Foreman agreed with the principles behind Ali’s inspired strategy.

“When you’re young like that and you’ve had so many knockouts, you don’t want to win by points, you want to knock them out,” Foreman told NBC’s Marv Albert in 1990. “If I had to do it all over again, I’d just win the fight on points and not worry about it. If he didn’t want to come out in the middle of the ring, forget him. If he don’t want the championship of the world… that kind of thing. He fought just like your initial bum, just lay on the ropes and take a whipping. That’s normally what a bum would do. But this time he did it with character. He said, ‘I’m going to weather this storm and I’m going to whip George Foreman.’ (The “Rope-a-Dope” didn’t surprise me at all) because normally when I fight a guy that’s all he can do anyway; just get on the ropes and just hope that he doesn’t get hurt. And if you happen to lay on the ropes, and George Foreman becomes a dope, you win the fight.” (16)

Lying on the ropes alone didn’t win the fight for Ali; it just created the environment by which he could win. As Foreman whaled away with impunity — and growing inaccuracy — a wide-eyed Ali scanned for openings and seized on almost every one of them. Foreman’s ever-wider punches created a causeway down the middle for Ali’s spearing jabs and lightning-quick right leads that snapped the champion’s head and puffed his face.

The fourth round saw Ali out-land Foreman for the first time in the bout (15-12 overall) and his wickedly accurate counter shots connected at a 75% rate (12 of 16). Foreman, however, went all out in the fifth as he landed 26 of his 93 total punches and 23 of his 65 power shots, all fight highs. Statistically speaking, Ali answered Foreman’s surge with stiletto-sharp punching. In round five Ali was 19 of 37 overall (51%) and 10 of 17 with his power punches (59%). But as much as Ali’s punching affected Foreman, his mouth dished out even more punishment. Every time the fighters fell into a clinch Ali leaned in and dug verbal daggers that pierced Foreman’s psyche.

“Hit harder! Show me something, George,” Ali demanded. “That don’t hurt. I thought you were supposed to be bad.” Then, twisting the knife even further, he asked Foreman, “is that all you got?”

“Yep, that’s about it,” Foreman recalled thinking at that moment. (17)

For Foreman, one particular moment in round three inflicted untold psychological damage. During a round that was one of Foreman’s best, the champion landed a series of crunching body shots that he felt would be enough to finish the job.

“I went out and hit Muhammad with the hardest shot to the body I ever delivered to any opponent,” Foreman told Hauser. “Muhammad cringed; I could see it hurt. And then he looked at me, he had that look in his eyes, like he was saying ‘I’m not gonna let you hurt me’. And to be honest, that’s the main thing I remember about the fight. Everything else happened too quick. I got burned out.” (18)

As that round closed, Ali rattled in a right-left-right to the face that allowed him to escape the ropes and a stinging one-two at ring center that landed painfully flush. When the bell sounded, Ali whirled around and fixed a defiant stare that said, “I will not be denied.”

The remainder of the fight was a fast-paced series of skirmishes marked by Ali’s counters, clinches and chatter and Foreman’s increasingly slower and more ponderous punches. Despite his growing exhaustion, Foreman never stopped throwing and at times he looked awkward as he tried to push his gloves past the thicket of Ali’s arms. By the sixth Ali was hitting Foreman virtually at will and by the eighth the older and lighter Ali was able to maneuver the monstrous champion into any position he chose.

Following his peak performance in the fifth, Foreman sagged to 12 of 50 overall in the fifth and 16 of 49 in the sixth. Ali, on the other hand, continued to puncture Foreman with well-aimed spears as he landed 45% of his jabs in the fifth (9 of 20) and sixth (13 of 29) while his power punching was downright surgical (10 of 17, 59%, in round five and 6 of 8, 75%, in the sixth).

The pattern of the fight was stunning and the wisdom of Ali’s strategy was finally dawning on the shocked audience. Despite the crippling exhaustion that enveloped him, Foreman continued to charge in because he knew no other way to fight. In the seventh he out-landed Ali 16-13 only because he nearly doubled Ali’s output (49-26). Meanwhile, Ali continued to strike with impressive precision (13 of 26, 50% overall, 6 of 9, 67% power).

While many believed the fight would not go the full 15 rounds, nearly everyone believed the champion would be the one who would apply the finisher. Now, with Foreman hurtling toward exhaustion, the possibility of Ali emerging victorious in a shortened fight was a growing likelihood.

To the world’s utter astonishment, that likelihood soon became reality.

With 20 seconds remaining in round eight, Ali began his final assault by landing a lancing right that nailed the onrushing Foreman. That was followed by a right to the temple that turned Foreman’s body and left it draped over the top rope. As Ali pivoted toward ring center he landed a third right to the forehead, then a devastating hook-cross to the face that sent Foreman stumbling and falling heavily to the canvas on his right side. As the crowd exploded in celebration, Ali calmly stood in the neutral corner as referee Clayton stood over the champion and tolled his count.

Foreman finally began to stir at six and by eight he managed to climb to a knee. But Clayton, for reasons only known to him, crisscrossed his arms after tolling eight and stopped the fight.

Technical questions aside, the awe-inspiring force of the moment was overwhelming. Members of the “Ali Circus” rushed the ring and Ali’s brother Rahaman tried to lift the new champion in the air, but a clearly agitated Ali slapped his sibling’s arm away with his left glove, then sat on the canvas to get away from the swirl of joy that orbited him. Dozens of spectators flooded the ring and several of them broke into dance. The scene soon spiraled out of control as a ring stool was tossed toward Ali and dozens of white-helmeted riot police struggled to quell the pandemonium.

As a sad, dejected and depleted Foreman exited the ring, the triumphant Ali led another round of “Ali, bomaye” chants.

At the time of the stoppage Ali led on all three scorecards — 70-67 according to Tunisian judge Nourridine Adalla, 69-66 on American James Taylor’s card and 68-66 by Clayton’s account. Foreman’s ferocious, but ultimately futile, attack still allowed him to out-land Ali 138-125 overall and 109-63 in power shots but Ali’s dominant jab (62-29), searing accuracy (48% overall, 40% jabs, 58% power) and ability to block most of Foreman’s bombs (30% overall, 19% jabs, 35% power) created a fusion of circumstance that led to a wondrous and historic victory.

At long last, Ali’s odyssey had reached its end. Ali became only the second man to date to regain the heavyweight championship and unlike many of those who would follow him his claim was undisputed.

As he did after he stopped Liston more than a decade earlier, Ali took time to chide his doubters.

“Everybody stop talking now. Attention!” he said in the dressing room.

“I told you, all of my critics, I told you all that I was the greatest of all times when I beat Sonny Liston. I told you today I’m still the greatest of all times. Never again defeat me, never again say that I’m going to be defeated, never again make me the underdog until I’m about 50 years old.” (19)

Ironically, it would be Foreman who would still be in boxing until nearly age 50. Long after Ali retired, came back and retired for good after back-to-back losses to Larry Holmes and Trevor Berbick, Foreman emerged from a 10-year layoff, lost a stirring challenge of Evander Holyfield at age 42 then, wearing the same trunks he wore two decades earlier in Kinshasa, fired the right hand heard around the world and regained the heavyweight championship from Michael Moorer at the age of 45 years, 310 days. The 20-year gap between championship reigns is — and probably will forever be — the longest in boxing history. But more importantly for Foreman, the victory allowed him to exorcise the ghosts that had haunted him since his nightmarish experience in the African jungle.

Now it was Foreman’s turn to feel the rush Ali must have when he scored his massive upset two decades earlier. The crowd inside the MGM Grand produced noise so cacophonous that it could be heard far beyond its confines. The commotion was at least the equal of the post-fight scene in Zaire and that, in effect, helped close the circle for Foreman.

Armed with his religious faith, the incisive perspective of a middle-aged man who had seen it all and done it all and the peace that came with his historic triumph over Moorer, Foreman — who once had blamed the Ali loss on poisoning — had a different outlook on what transpired against Ali.

“When I look back on it, devastated at that time as I was from losing the fight, I’m just happy that I didn’t win it,” Foreman told “Facing Ali” author Steven Brunt. “I’m just happy that I didn’t land that big shot and knock him out. Boy, am I happy about that. Because you could have changed everything then. The second chances. Even now, with Muhammad Ali being proclaimed The Greatest. Everything could have been messed up.

“It’s harmony to me when I hear people say Muhammad Ali is The Greatest,” he continued. “When they call him The Greatest and he walks around and people give him standing ovations, I’m thinking he deserves it. He deserves it. Life is a rough journey with a lot of problems. A lot of things happen to you. If a person can leave with some applause, amen to them. I think of the Sonny Liston fight, maybe the Joe Frazier Thrilla in Manila, and the George Foreman fight — you take any pieces of that puzzle away and you don’t crown him that. Then I get a second chance to come back because of the devastation with that fight. It forced me to just turn over every stone. ‘What’s wrong? I’m not supposed to lose. Something is wrong here.’ I couldn’t figure that out. And eventually having a fight with Jimmy Young, trying to become the number-one contender, pushing myself to my limits just to go 12 rounds made me fall into the hands of God. And if any one of those little things….it was that fragile, that one little thing (beating Ali) could have messed the whole thing up. And my world could have been totally different. Muhammad Ali’s world, Joe Frazier’s. All of us. The world could have been different for us. Because of the trials Muhammad is going through, he should have that (being called “The Greatest”). I wouldn’t want anyone else to be that, especially myself.” (20)

In that vein, it can fairly be said that, by beating Foreman, Ali had erected the final pillar of his fistic legacy, not just by regaining the championship, but doing so as an older fighter against a younger, stronger and more ferocious version of Sonny Liston. The long march to regain the crown taken from him by outside forces was now complete. The argument of his merit as a fighter was now settled. What he said from the very beginning of his career — even before he had logged one notable accomplishment — still applies now: When one combines in-ring feats with worldwide fame that transcends boxing’s confines, Muhammad Ali cemented himself as the greatest star boxing had ever known — and may ever know.

INSIDE THE NUMBERS: Ali landed 66% or higher with his power punches in four of the last five rounds — 75% in the 4th (12 of 16); 75% in the 6th (6 of 8); 66.7% in the 7th (6 of 9) and 68.8% in the 8th (11 of 16) — far higher than the heavyweight average of 40.8%. Ali landed 57.8% of his power punches in the fight, his second highest percentage of the 47 fights tracked by CompuBox (his 62.2% accuracy in the Cleveland Williams fight was the highest). The weary Foreman landed just 28 power punches in the last three rounds after landing 54 in the previous three rounds.

Footnotes:

(1) “Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times,” by Thomas Hauser, Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, 1991, p. 263-64

(2) Ibid, p. 264

(3) “Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times,” by Thomas Hauser, Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, 1991, p. 260

(4) Ibid, p. 260

(5) “By George: The Autobiography of George Foreman,” by George Foreman and Joel Engel, Villard Books, 1995, p. 98-99

(6) Ibid, p. 101

(7) “Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times,” by Thomas Hauser, Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, 1991, p. 266

(8) “Revisiting ‘The Rumble in the Jungle,’ ” by Josh Peter, USA Today, October 29, 2014, published on the Louisville Courier-Journal website

(9) “Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times,” by Thomas Hauser, Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, 1991, p. 264

(10) “No Ali-Foreman Bout Until Late-October,” by Thomas A. Johnson, New York Times, September 18, 1974

(11) “Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times,” by Thomas Hauser, Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, 1991, p. 273

(12) “Ali Outfought, Outlasted and Outwitted Foreman in a Classic Upset,” by Nat Loubet, THE RING, January 1975, p. 6

(13) Ibid, p. 8

(14) “Shadow Box,” by George Plimpton, Berkeley Publishing Corporation, 1971, p. 303 (paperback version)

(15) “Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times,” by Thomas Hauser, Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, 1991, p. 277

(16) “Greatest Fights Ever: The Rumble in the Jungle,” NBC, aired in April 1990

(17) Ibid

(18) “Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times,” by Thomas Hauser, Simon and Schuster Paperbacks, 1991, p. 277

(19) “Greatest Fights Ever: The Rumble in the Jungle,” NBC, aired in April 1990

(20) “Facing Ali: The Opposition Weighs In,” by Stephen Brunt, The Lyons Press, 2002, p. 188-89