Book excerpt celebrates the best of Muhammad Ali in the 1960s

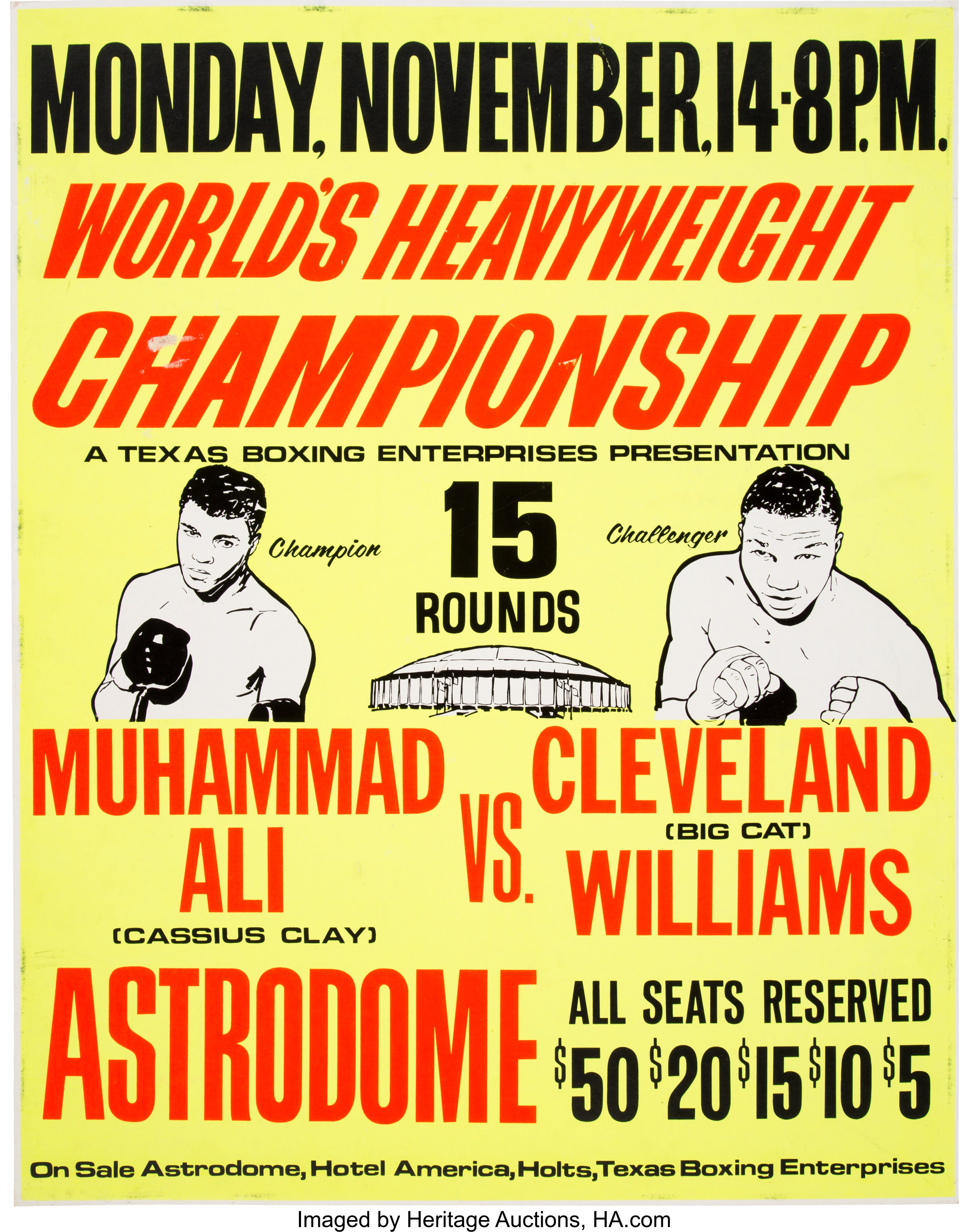

Five years ago today, Muhammad Ali died in Scottsdale, Arizona, at age 74, following a respiratory illness complicated by his decades-long battle with Parkinson’s Disease. The tributes from around the world were voluminous and heartfelt, and the public memorial service staged on June 10, in Louisville, Kentucky, was watched by an estimated one billion people. Ali’s impact on his chosen sport is everlasting and in honor of his legacy, RingTV.com will present two excerpts from “Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers,” written by CompuBox founder and President Bob Canobbio and RingTV.com’s own Lee Groves. This first installment, his third-round TKO of Cleveland Williams, on November 14, 1966, in Houston, Texas, represents the very best of the 1960’s version of Ali – if not the very best Ali ever seen inside a boxing ring. It was a transcendent performance that produced a rare fusion of lightning speed and unassailable power that persuaded even some of his critics that he was a superlative athlete. Without further delay, here is the story of Ali-Williams.

*

Every so often, an athlete — even one who long had been considered elite — will produce a performance that shatters all pre-conceived limits of human accomplishment. At the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City, Bob Beamon’s first leap of the competition, a 29-foot 2 1/2-inch bomb, crushed the previous world record by an astonishing 21 3/4 inches. On March 2, 1962 in Hershey, Pa., Wilt Chamberlain smashed his own NBA single-game scoring record of 78 by pouring in 100 points, a mark that hasn’t been seriously challenged since. And on September 28, 1951, L.A. Rams quarterback Norm Van Brocklin — who that day was subbing for injured starter Bob Waterfield — obliterated Johnny Lujack’s single-game passing record of 468 yards by accumulating 554 yards on just 27 completions, a total that still stands despite the league’s pass-happy approach in recent years. (1)

For Muhammad Ali, the peak was reached November 14, 1966 at the Houston Astrodome against Cleveland Williams. During seven minutes and eight seconds of ring action, the 24-year-old Ali’s already balletic footwork soared to new heights thanks to his frequent use of the newly-created “Ali Shuffle” while his hands produced combinations that landed with stunning power and frequency. At the same time, he transitioned seamlessly between offense and defense to a degree never previously seen. When historians assess Ali’s chances against other all-time greats, it’s the Cleveland Williams fight they use, appropriately, to measure Ali at his best. Of that night, Howard Cosell later declared, “he was the most devastating fighter who ever lived.” (2)

That said, even Ali conceded that the 33-year-old Williams wasn’t the fighter he had been in the late-1950s and early 1960s. That fighter had been one of his era’s most dangerous punchers — and one of its most avoided.

Standing 6-foot-3 and owning an 80-inch wingspan, Williams could look Ali in the eye and also jab from equal distance. But it was his enormous two-fisted power that separated him from the pack as well as separated opponents from their senses. Entering the Ali bout, 53 knockouts adorned his 67-5-1 record, including 18 straight between March 1952 and January 1953. Yes, some of those victims had names like Graveyard Walters (KO 2), Baby Booze (KO 1) and Candy McDaniels (KO 2), but fights are fights, punches are punches and knockouts are knockouts.

While Williams made his bones knocking people out, his two most famous fights were the pair he lost to future champion Sonny Liston in April 1959 and March 1960. While Williams was stopped in rounds three and two respectively, he managed to stun “The Big Ugly Bear” in both bouts.

Since the Liston rematch in Williams’ native Houston, “The Big Cat” had gone 20-1-1 with 14 knockouts. But Williams was a 15-year ring veteran who not only was growing long in the tooth, he also entered the Houston Astrodome ring with a policeman’s .357 magnum bullet in his gut, the result of a confrontation with a Texas highway patrolman on November 29, 1964.

“Williams and three friends, two of them females, were arrested for drunken driving,” wrote THE RING’s Dan Daniel. “Cleve, who, according to (manager Hugh) Benbow, had had only a few beers, pleaded with the cop to let him go. He pleaded that his scheduled match with (WBA champion Ernie) Terrell (which had been announced just nine days earlier) would be in jeopardy if the news of his arrest got out. The patrolman refused and a scuffle ensued. Williams was shot.

“After an operation which lasted five-and-a-half hours, Cleve was sewed up and put to bed,” Daniel continued. “Half an hour later he had to be operated on again, as he had been bleeding internally.” (3)

According to the Associated Press, Williams was in critical condition for several weeks and underwent four operations over a seven-month period. Benbow later revealed that Williams had “died” three times during the initial operation and, during his recovery, his weight had plummeted to 158. (4)

Muhammad Ali vs. Cleveland Williams

In the end, Williams persevered.

“This man has an iron constitution, a body of steel,” the chief surgeon said. “I believe he will be fighting again. But it will take some time.” (5)

That time ended up being a little more than 14 months. Williams’ first fight was a one-round blowout of Ben Black on February 8, 1966, which was quickly followed by victories over Mel Turnbow (an off-the-floor W 10) on March 22, Sonny Moore (W 10) on April 19 and Tod Herring (KO 3) on June 28, all of which were staged at the Sam Houston Coliseum in Houston. While the bout, on paper, appeared heavily tilted toward the defending champion, the matchup proved so attractive that it drew 35,460, which broke an indoor attendance record that had stood for a quarter-century. (6)

Despite the obvious differences in talent, career trajectory and ring wear, no one could have anticipated how severe a mismatch Ali-Williams would end up being.

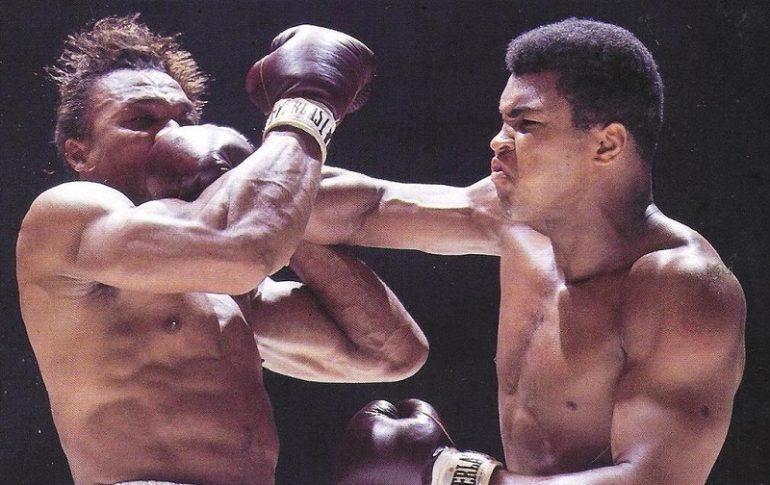

Ali spent the first round on the move, firing a jab that easily sliced through Williams’ guard and shooting power shots judiciously but accurately. Even this study-hall version of Ali left the far slower Williams at a loss, for he only got off 13 punches in the round, landing three. Meanwhile, Ali breezily landed 23 of his 50 total punches, 15 of his 33 jabs and 8 of his 17 power shots.

Of the 548 rounds Ali fought as a pro, round two of the Williams fight ranks as one of his very best. The statistics alone were awe-inspiring as he landed 38 of his 64 total punches (59%), 22 of his 38 jabs (58%) and 16 of his 26 power punches (62%). But the numbers only partially illustrated Ali’s mind-boggling blend of speed and power.

Jabbing to the head, Ali bloodied the challenger’s nose. Then, with 47 seconds remaining, Ali scored the first knockdown with a sudden one-two to the jaw. The determined Williams rose immediately but was soon staggered by a chopping right to the temple and dropped with a pinpoint right-left-right to the face. Again, Williams got up quickly and braced himself for the next wave.

With the end of the round fast approaching, Ali delivered the most picturesque combination of his career — two flush hooks followed by a gorgeous right to the chin that left Williams flat on his back. In most jurisdictions the fight would have ended there, but since there was no three-knockdown rule, the challenger was given the opportunity to rise. Had the knockdown occurred earlier in the round, the semi-conscious Williams probably wouldn’t have been able to do so, but because the bell sounded midway through referee Harry Kessler’s count, Williams’ manager and corner people were allowed to enter the ring and help their man back to his stool.

The 60-second rest only delayed the inevitable; for on this night Ali was unstoppable. As great as the second round was, the third was Muhammad Ali at his white-hot zenith.

It began with Ali jabbing Williams with spears, then, after yet another shuffle, bedazzling him a pair of four-punch combinations that landed hard and flush. An instant later, Ali scored the fourth knockdown with a missile of a right hand. Once again, Williams got up well before Kessler reached the halfway point of his count and once the fight resumed he tried his best to keep the Ali storm at bay.

He could not.

A right to the ear caused Williams to stumble, and after a final right crashed on Williams’ jaw, the referee stopped the slaughter. In those 68 seconds, Ali threw 42 punches and landed 26 for 62% accuracy and connected on 22 of his 31 power punches, which translates to 71%.

Conversely, Williams threw just 12 punches in the round, striking Ali with only three. For the fight, Williams hit Ali 10 times, and eight of those were jabs. The Williams fight was Ali’s fifth title defense of 1966 and his fourth straight knockout.

Ali’s performance left observers awestruck. Many of the 35,460 that generated a $461,780 gate booed and hooted at Ali during his approach to the ring but once they witnessed the full array of Ali’s talent they gave him an ovation upon leaving. (7)

RING founder Nat Fleischer, a longtime ally of Ali’s, called his performance “splendid” and “the best of his career.”

“I have seen, and been with, Clay on all of his foreign trips since the Rome Olympic Games, and at no time have I seen him unleash such power as against Williams,” he wrote. “In contrast to other performances, Cassius was a fighting machine in Houston. Once he unlimbered his heavy artillery, he faced a confused, bewildered, floundering opponent who was baffled by what was taking place. The unexpected had happened and the fans saw a one-sided affair.” (8)

Ali’s display also caused some critics to change their tune.

“I kept saying he was a phony, a clay pigeon, but I take it all back,” declared Benbow. “I apologize. He made a sucker out of me and my boy. He made a believer out of me. He’s the real McCoy. I’m now convinced of his punching ability. He’s a real champion. Let’s not kid ourselves any longer.” (9)

Ali’s most surprising convert was none other than the legendary “Manassa Mauler,” Jack Dempsey.

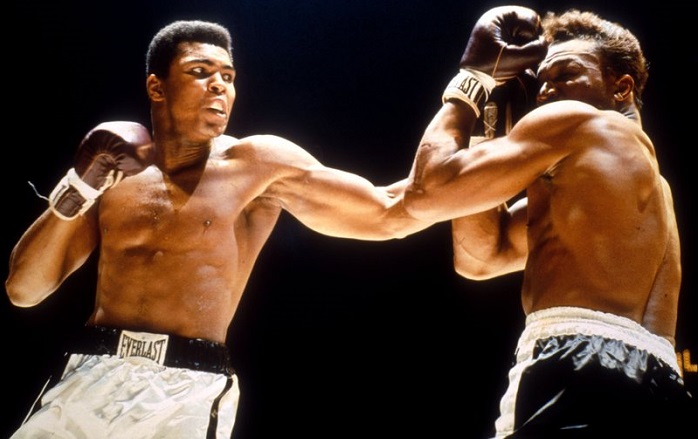

Muhammad Ali (left) vs. Cleveland Williams. Photo credit: Popperfoto

“He is fast, both with his hands and with his feet,” he said. “His reflexes are amazing. You might expect them in a lightweight, but not in a man of his size. He showed he can take a man out. Williams was through when the bell saved him at the end of the second round. I guess we’re lucky to have him around.” (10)

He didn’t win over everybody, however. In the same issue of THE RING in which Dempsey offered praise, Joe Louis opined an “as told to” article in which he detailed “How I Would Have Clobbered Clay.” In fact, “The Brown Bomber’s” article began on page six while Dempsey’s started on page seven.

But while Benbow and Fleischer were amazed, Williams was puzzled.

“I didn’t know what was going on after Clay smashed his right to my mouth in the second round,” he said, “I don’t remember the other knockdowns.”

Asked whether he was ever hit harder, he said, “he was not the hardest hitter I’ve met.” (11) It’s only a guess, but that honor probably still belonged to Liston.

Years later, Williams gave voice to the most common criticism leveled against those who declared this Ali’s best performance — he fought a badly eroded version of the “Big Cat” that had so terrorized the heavyweight class years earlier.

“(Ali) wouldn’t fight me before I got shot, him or Floyd Patterson,” he said in 1979. “But when I did fight him, even a little kid could’ve beaten me.” (12)

Despite Ali’s tremendously accomplished 1966 campaign, THE RING’s editors chose to bypass him — and everyone else — for the publication’s Fighter of the Year award.

“Since 1963, Clay has disqualified himself for a repeat award with these demerits: 1. Cassius allied himself with the Black Muslims, who avowedly are not friendly toward the United States of America, and are not listed as a patriotic group; 2. Clay has entered a protest against his being drafted into the Army, and has laid claim to exemption from service, chiefly on the allegation that he is a student-preacher for the Mohammedan religion; 3. The champion boxer of the world has been guilty of utterances which have not redounded to the credit of boxing and which, arousing the vehement protests of the American Legion, Veterans of Foreign Wars and other patriotic organizations, forced cancellation of Clay’s scheduled fight with Ernie Terrell in Chicago and had other bad repercussions.” (13)

Dan Daniel, who wrote the editorial that appeared in the March 1967 issue, said that denying Primo Carnera of the 1933 award due to the shady nature of his management was adequate precedent for their stance against Ali, a stance which was said to have been received favorably by a 6-to-1 margin in the following month’s edition. (14)

When asked for his reaction by RING founder and editor-in-chief Nat Fleischer, Ali was disappointed.

“I’m a fighting champion,” he declared. “I’m sorry Nat Fleischer’s magazine didn’t award me the honor. My record for 1966 entitled me to be named. My religious belief should have not been considered. It has nothing to do with my fighting ability. Sportsmanship, ring achievement and clean living should decide. In those I know I stood out for the year 1966.” (15)

Fifty years later, a new editor from a new generation opted to alter the record and retroactively bestow the honor on Ali.

“While many took issue with the Nation of Islam — many still do — we feel that athletes under consideration for such awards should be judged by their performance, not their political or religious affiliations,” then-RING editor-in-chief Michael Rosenthal explained in the March 2017 issue. (16)

The Williams fight was the final one of Ali’s 1966 campaign, and when his fighting career was suspended the following year, the Williams fight would stand out as an aching hint of what might have been had history unfolded differently.

Muhammad Ali vs. Cleveland Williams. Photo credit: Neil Leifer/Authentic Brands Group

INSIDE THE NUMBERS: Ali’s numbers vs. Williams were spectacular. He landed personal bests among fights counted for total connect percentage (55.8% — heavyweight average: 34%), jabs (50% — more than doubling the division average of 25.5%) and power punches (62.2%, far above the divisional norm of 40.7%). Meanwhile the bedazzled Williams threw just 43 punches in 7:08 of ring time and landed just two power punches.

Footnotes:

(1) “Still the Biggest Passing Day,” by Judy Battista, New York Times, September 27, 2011

(2) “Was This Muhammad Ali at His Greatest?,” by Matt Christie, Boxingnewsonline.com, November 14, 2016

(3) “Where Do Our Heavies Stand Now?” by Dan Daniel, THE RING, February 1965, p. 6

(4) “Army? Terrell? Where is Clay Headed,” by Dan Daniel, THE RING, March 1966, p. 8

(5) “Where Do Our Heavies Stand Now?” by Dan Daniel, THE RING, February 1965, p. 6

(6) “Great KOs,” by Jimmy Jacobs, THE RING, October 1980, p. 90

(7) “Clay Showed Sock as Well as Science,” by Nat Fleischer, THE RING, February 1967, p. 38

(8) Ibid, p. 38

(9) Ibid, p. 38

(10) “Dempsey’s Startling New Opinion of Cassius: Clay’s Early KO over Cat Prompts Jack to Shift Tack,” by Al Buck, THE RING, February 1967, p. 38

(11) “Clay Showed Sock as Well as Science,” by Nat Fleischer, THE RING, February 1967, p. 38

(12) “Tracking the Cat,” by Mark Seal, Scene Magazine, a supplement of the Dallas Morning News, reprinted in the January 1980 issue of THE RING, p. 50

(13) “No Fighter of the Year: Clay’s Fine 1966 Record Discounted by Refusal to Accept Army Draft,” by Dan Daniel, THE RING, March 1967, p. 6, 58

(14) “Ring Readers Back Bypass of Clay for 1966 Citation,” by Dan Daniel, THE RING, April 1967, p. 28

(15) “Louis Clobber Me? He Must Be Joking — Clay,” by Nat Fleischer, THE RING, May 1967, p. 34

(16) “Belated Justice,” by Michael Rosenthal, THE RING, March 2017, p. 54

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE