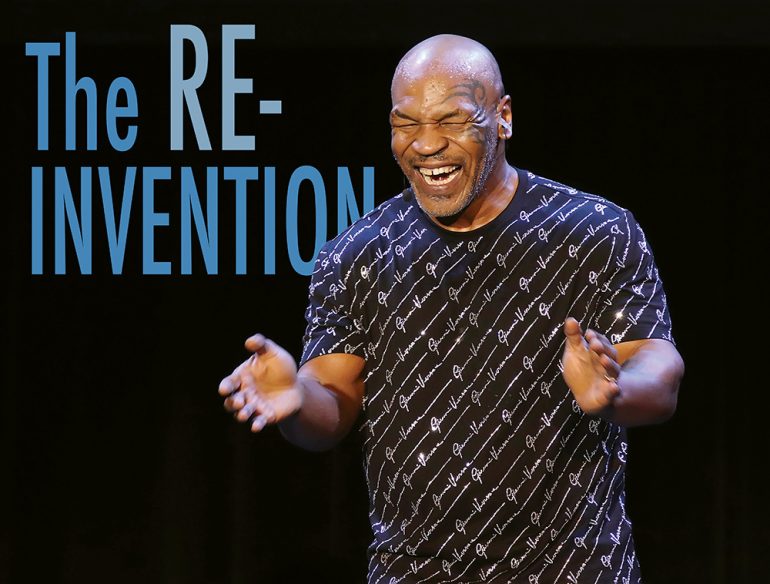

The Reinvention

The following story originally appeared in the September 2020 issue of The Ring Magazine. It recently received first-place honors for “Feature Under 1,500 Words” at the BWAA 2020 awards.

FROM CANNABIS ADVOCACY TO SHOWBIZ, MIKE TYSON HAS MATURED, MELLOWED AND THRIVED IN HIS POST-BOXING LIFE – AND THE PUBLIC IS AS HOOKED AS EVER

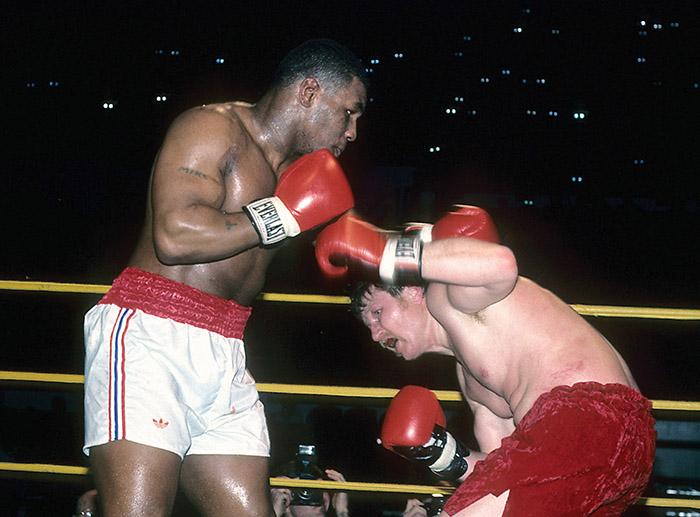

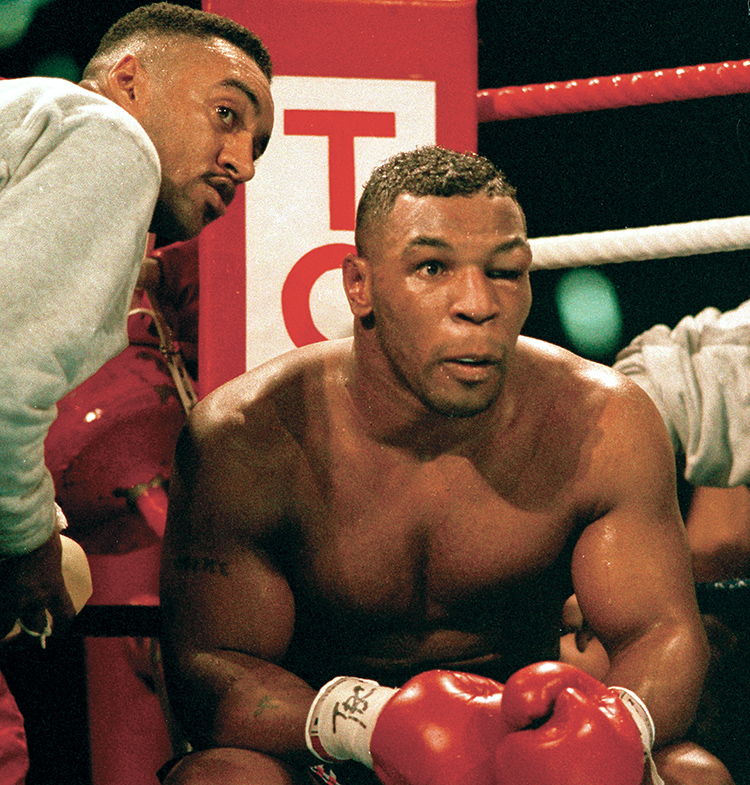

Tribal face tattoo. Crunching uppercuts. A bit of head movement, remarkably quick hands. Yes, it was Mike Tyson, looking sharp on Instagram after being gone from the ring for 15 years. Though he hinted he was getting in shape for some charity exhibitions, the story snowballed into rumors of a full-fledged comeback. When Tyson was eventually seen horsing around with some professional wrestlers on TNT, a groan was heard across the land. Had we been played? Still, the sight of Tyson working the pads again had a delirious effect on the less-than-rational social media gang, something akin to film scholars learning that Akira Kurosawa was not only still alive, but working on an alternate cut of Seven Samurai. Whatever one thought of the 53-year-old Tyson’s alleged mission – whether he would, as some believed, mount an assault on the heavyweight class, or end up getting hurt – the general reaction was a triumph for Tyson, the final proof of his reinvention.

The amending of the Tyson image has been an ongoing effort in the past decade. His transformation from prizefighting psychopath to white-bearded cannabis tycoon was inspiring to observe. After all, he’d lived a tabloid-ready life and at one time seemed destined for a tabloid-ready death. But Tyson’s new mellow persona – the vegan capitalist blissed out on weed – was at odds with his legacy as a tough guy. A recent episode of his merry podcast, Hotboxin’ with Mike Tyson, saw him turn emotional as he recalled his violent heyday. He was tired, he said, of feeling like “a bitch.” Under the pot haze, the old tiger still prowled.

A gray-bearded Tyson interviews Sugar Ray Leonard on his popular podcast.

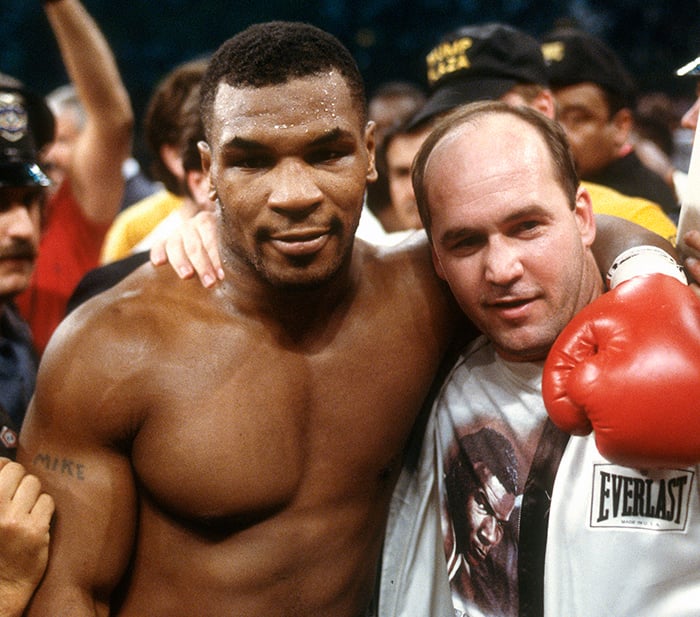

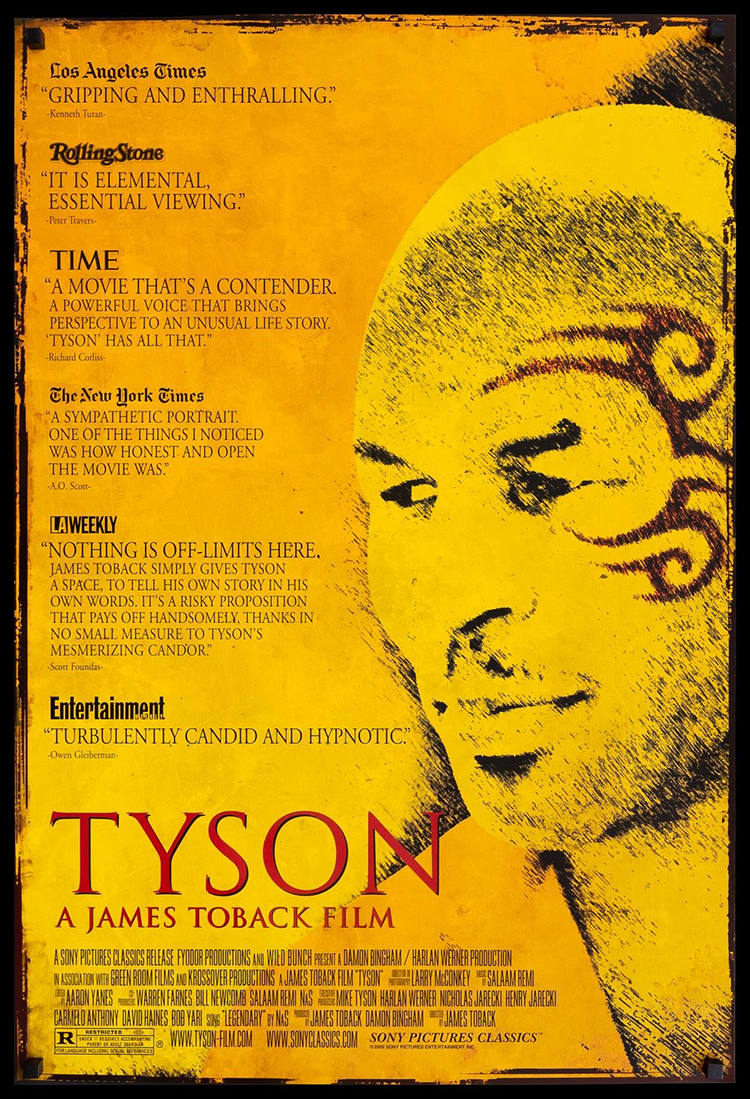

Though details of his comeback remained murky, it didn’t appear to be driven by money. In the 2010s, Tyson worked constantly, rebuilding himself as a sort of roving raconteur, an idea possibly inspired by his candid turn in James Toback’s 2008 documentary. That movie, which bore only Tyson’s last name as its title, wowed the film festival circuit and proved the Tyson saga had legs. Since then, whether promoting his ghostwritten autobiographies or working himself into a lather during his one-man stage show (later presented as an HBO special), Tyson developed a storyteller’s gift for turning his past into shtick. One moment he’s recalling the time he nearly beat up Brad Pitt, then he’s telling about offering a zookeeper $100,000 because he wanted to fight a silverback gorilla. Talking keeps Tyson flush.

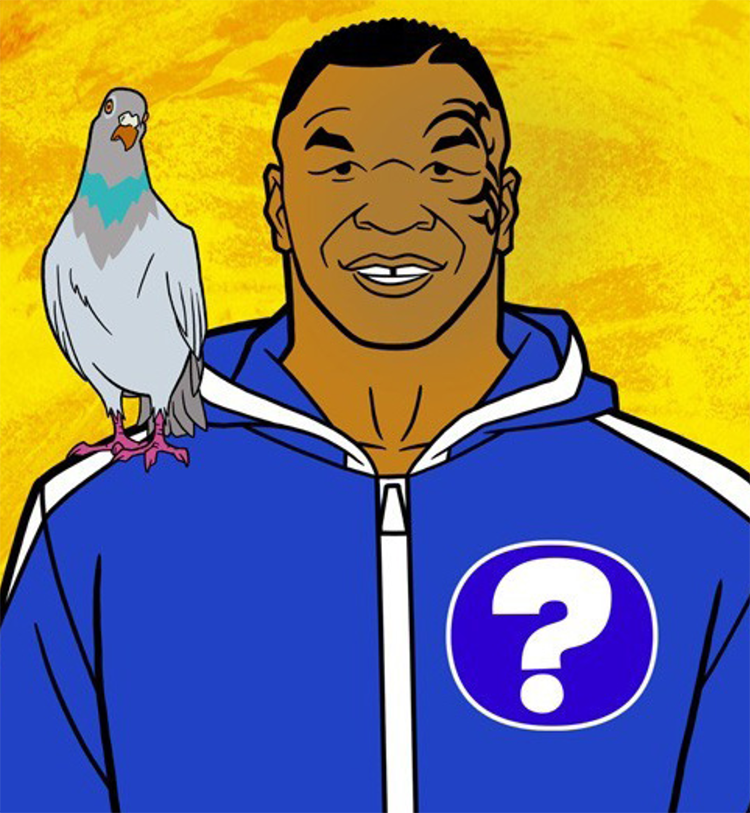

As if to counterbalance the harrowing tone of his more serious work, Tyson has also shown a comical side in movies, commercials and television programs. Perhaps the most intriguing development in this regard is Mike Tyson Mysteries, an animated series where Tyson and some pals investigate crimes, a la Scooby-Doo. As of 2020, there have been 70 episodes of the Tyson cartoon; to put this in perspective, there were only 68 episodes of The Huckleberry Hound Show and a meager 16 of Josie and the Pussycats. Strange as it is to see Tyson as part of Cartoon Network’s nighttime lineup, it’s another example of the creative and versatile way he’s thrived in retirement. There’s little he won’t do. He once appeared on Italian television to playfully spar with a young girl, and even inhaled helium on Jimmy Kimmel Live!, changing his voice into a Gollum-like croak.

Of course, part of Tyson’s charm is that he’s still a bit of a rube. During a New York Public Library event, for instance, he was asked why so much of his first autobiography was printed in italics. “I don’t know,” Tyson said. “What are italics?” On his podcast, where guests range from Mickey Rourke to Eminem, Tyson is occasionally so baked that he appears sleepy. Sometimes the conversation veers clumsily into something like group therapy; when Ray Leonard was his guest, the two kept weeping over incidents from their turbulent pasts. Tyson’s co-host, former NFL player Eben Britton, often provides positive reinforcement with lines like, “You’re such a good man, Mike.”

Of course, part of Tyson’s charm is that he’s still a bit of a rube. During a New York Public Library event, for instance, he was asked why so much of his first autobiography was printed in italics. “I don’t know,” Tyson said. “What are italics?” On his podcast, where guests range from Mickey Rourke to Eminem, Tyson is occasionally so baked that he appears sleepy. Sometimes the conversation veers clumsily into something like group therapy; when Ray Leonard was his guest, the two kept weeping over incidents from their turbulent pasts. Tyson’s co-host, former NFL player Eben Britton, often provides positive reinforcement with lines like, “You’re such a good man, Mike.”

Something must be working. Five and a half million Twitter followers couldn’t be wrong.

Tyson’s post-career appeal is due to a knot of factors. First, the untamed party monster who has survived to tell the tale satisfies the gawker in all of us. Second, our fetish for youth, and the belief that the youngest heavyweight champion in history was somehow more special than someone with a longer apprenticeship. Third, our obsession with bad boys – our forgiving nature is hopelessly intertwined with our innate ability to recall criminal behavior as merely rebellious, where even a sex fiend and serial ass-grabber is remembered as just a rascal. Fourth, nostalgia for the 1980s, a tumultuous and scary decade that seems rather fun in retrospect. Fifth, a generation brought up in the era of political correctness and an unsteady economy sees Tyson the way our great-grandparents saw figures of the Old West: as a symbol of freedom and reckless bravado. Sixth, a fascination with vulgarians; give $300 million to an uneducated street kid and see what happens. And seventh, the audience’s nervous appetite for public meltdowns: Charlie Sheen, Lindsay Lohan, Tyson. All of these strands created a silky veneer around a fellow with a deplorable history.

It’s not all down to Tyson being a reformed carnival act. His life has the effect of a heroic fairy tale, one where a boy is plucked from obscurity by a wise old sensei named Cus D’Amato and trained to become a warrior, only to fall prey to wicked women and ruthless businessmen. It was a fizzy mix of Joseph Campbell and Jerry Springer, with a Public Enemy soundtrack. There was a prison sentence he insists was unjust, drug abuse, financial ruin and the personal tragedy of his 4-year-old daughter, Exodus, dying in a household accident. Tyson’s ability to withstand calamities and dig his way out of disasters is no doubt part of the public’s fascination with him, and possibly explains why at this year’s big boxing event between Tyson Fury and Deontay Wilder, Tyson received a much heartier ovation when introduced alongside Evander Holyfield and Lennox Lewis, two of his conquerors.

READ: Mike Tyson’s Comeback Isn’t for Legacy or Money, but for His Soul – by David Greisman

Of course, fighters have remade themselves ever since John L. Sullivan became a temperance speaker. Jack Dempsey became a successful restaurant owner, George Foreman a friendly TV pitchman. Mickey Walker’s primitive artwork was displayed in galleries around the country, and Muhammad Ali went from being one of the most controversial men in America to one of the most beloved. But Tyson’s relaunch has been alarmingly multi-faceted. We’ve had comedy Mike, confessional Mike and contrite Mike. We’ve had Broadway Mike, animated Mike and Mike the gentle stoner.

It is debatable whether these various versions of Tyson were deliberate efforts to change his persona – he’s always possessed a conman’s knack for shapeshifting – or were simply the natural result of his maturing. When he tweets “being kind to others allows me to be kind to myself,” it sounds like a line pulled from a cheesy self-help book. Obviously, portions of his makeover have been carefully orchestrated; he’s understood the importance of image and sound bites since the earliest days of his career. Yet he seems comfortable in his current incarnation. As an advocate for love and unity and meditation, he’s surprisingly likable. If nothing else, he’s a walking advertisement for the calming effects of marijuana.

I’m a Bad Boy for Life. Watch #BadBoysforLife now on DVD Blueray @realmartymar #willsmith #stillthebaddestmanontheplanet pic.twitter.com/R9Zmz19GFm

— Mike Tyson (@MikeTyson) May 1, 2020

Of the many comeback scenarios proposed, the one that sounded feasible was an exhibition for charity. Dempsey, one of Tyson’s heroes, fought exhibitions around the country to help his bank account during the Great Depression. Dempsey’s tour drew crowds and made people happy, as he gave a tired America a taste of the old Jazz Age. Could Tyson do something similar? Could a country gutted by the coronavirus and civil unrest be temporarily buoyed by memories of parachute pants and Mike Tyson’s Punch-Out!!?

When Tyson boxed an exhibition with Corey “T-Rex” Sanders back in 2006, customers in Youngstown, Ohio, jeered. Not only were they bored at the sight of two overweight men lurching around the ring, but it was too soon after the debacle of his last fight, an embarrassing loss to Kevin McBride. That night ended with Tyson walking back to his dressing room under a rain of beer cups, literally giving fans the finger as he slinked away. It will be interesting to see the reaction this time around, should he really try the exhibition route.

There was something poignant about the now famous Instagram clip of an aged Tyson practicing a boxing drill. He was like an old showbiz trooper rehearsing a time-step, just in case he gets the call to perform. It also proved that Tyson’s grip on the public’s psyche never completely loosened. He’s no longer living his life out there on the edge, and there are probably badder men walking the planet, but he remains an indelible part of pop culture. He hovers above us like a parade float.

And how did the exhibition go? Read Dan Rafael’s recap.

THE TYSON TIMELINE

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE