Josh Taylor-Jose Ramirez continues revival of undisputed world champions

On Saturday, Jose Carlos Ramirez and Josh Taylor will attempt to produce an undisputed champion at 140 for the second time in less than four years. On August 19, 2017, WBC/WBO titlist Terence Crawford stopped WBA/IBF counterpart Julius Indongo in two rounds to become boxing’s first “four-belt” world champion since July 2005 when Jermain Taylor dethroned Bernard Hopkins. Ramirez-Taylor marks the continuation of a most welcome trend in boxing — the probable coronation of undisputed champions.

Saturday’s showdown represents the latest in a series of recent four-belt unifications that include Aleksandr Usyk-Murat Gassiev at cruiserweight, Claressa Shields-Christina Hammer at middleweight, Claressa Shields-Marie Eve Dicaire at super welterweight and the first Katie Taylor-Delfine Persoon match at lightweight. If one recognizes the legitimacy of the WBC’s “franchise” title — which this scribe doesn’t for a reason listed in the next paragraph — Teofimo Lopez’s points triumph over Vasiliy Lomachenko last October could be added to a steadily growing list.

Barring unforeseen circumstances, boxing will crown its fourth (or, in some eyes, its fifth) undisputed champion — the Ramirez-Taylor winner would join Lopez (with a caveat considering the presence of WBC “full” titlist Devin Haney, who is obligated to make timely WBC-mandated title defenses while Lopez is not) and female monarchs Taylor, Jessica McCaskill and two-division designee Shields (who has since vacated her WBA 154-pound title while keeping her other belts at 154 and 160). Better yet, the sport could add four more by the end of the year: Tyson Fury-Anthony Joshua at heavyweight, Saul Alvarez-Caleb Plant, Franchon Crews-Dezurn-Elin Cenderoos at super middleweight, and Jermell Charlo-Brian Castano at junior middleweight. Last week, Matchroom’s Eddie Hearn announced his intent to conduct a tournament to determine a new undisputed champion among the women at 140. Other divisions are in the process of consolidating title belts — six of the 15 female weight classes and 10 of the 17 divisions among the men feature at least one partially unified titlist — and The Ring ratings currently include nine world champions.

For the past several decades, fans, writers and some fighters have clamored for a return to a single world champion in every weight class, but that ideal has never been realized because the sport’s power brokers — promoters, managers, broadcast networks and sanctioning bodies among them — have profited mightily from the current system. Could it be that boxing is poised to achieve a happy medium in which a fighter can be the one and only champion in a given weight class while the powers-that-be retain the framework that has generated billions of dollars over the years? That remains to be seen, but it is clear that “the Sweet Science” is going back to the future when it comes to defining exactly what constitutes genuine supremacy over one’s peers — and over one’s era.

Here’s how: For the first several decades of the modern age, the mark of true greatness in boxing was a fighter’s ability to rule over a single weight class for years on end. The phrase “cleaning out the division” was a common one because that was the goal of the lone person sitting atop the division. Those who succeeded were looked upon with special favor, an impression that continued long after their retirements. Joe Louis recorded 25 consecutive title defenses in a reign lasting 11 years 255 days while featherweights Abe Attell and Johnny Kilbane produced back-to-back decade-long tenures, Archie Moore retained an iron grip on the light heavyweights for nine years and Benny Leonard and Jimmy Wilde dominated the lightweights and flyweights for more than seven years. All are enshrined in the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

The landscape began to change in August 1962 when the National Boxing Association became the World Boxing Association and when the World Boxing Council was created in 1963. With that, the era of perpetually divided world titles began, and while many fighters were able to produce years-long reigns over their jurisdictional slice, their legacies were somewhat clouded by the absence of fights against the “other” champion. How much better would it have been had WBC bantamweight champion Lupe Pintor and WBA counterpart Jeff Chandler fought, if WBC heavyweight champion Larry Holmes and WBA king Gerrie Coetzee followed through with a June 1984 superfight, had Carlos Zarate’s fourth-round KO over Alfonso Zamora in April 1977 had been an official bantamweight unification match instead of an “over-the-weight” contest or if Merida natives Miguel Canto and Guty Espadas Sr. had united their WBC and WBA flyweight titles before family, friends and the rest of the boxing world?

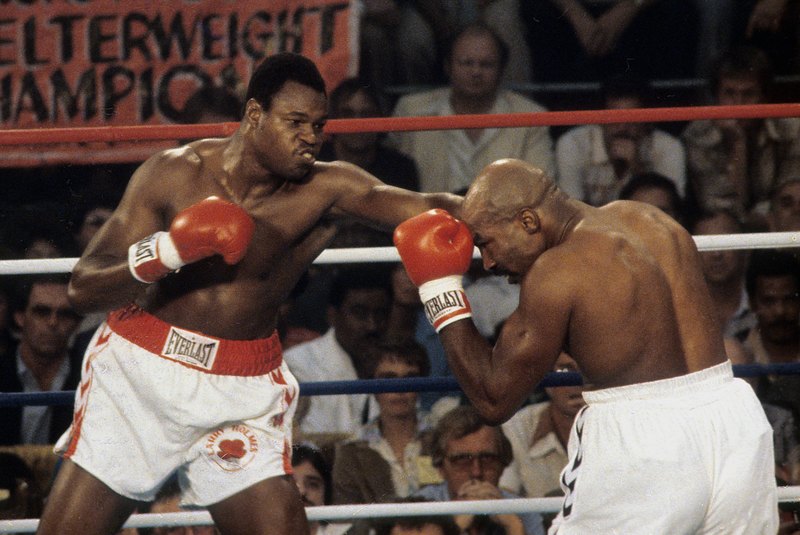

Larry Holmes (left), seen here against Earnie Shavers in their 1979 rematch, was the king of the heavyweights but never reigned as undisputed champion. Photo from The Ring archive

Because the WBA and WBC actively discouraged unification fights, a new definition of greatness emerged in 1981 when Wilfred Benitez and Alexis Arguello captured their third divisional championships within 28 days of one another thanks to Benitez’s 12th-round KO of WBC junior middleweight titleholder Maurice Hope on May 23 and Arguello’s comprehensive 15-round decision over WBC lightweight king Jim Watt on June 20. Incredibly, Benitez was the first to become a triple champion since Henry Armstrong turned the trick nearly 43 years earlier, and the rarity associated with their twin triumphs allowed “El Radar” and “El Flaco Explosivo” to separate themselves from their contemporaries. After all, Benitez and Arguello joined a roll call that had previously consisted of only four legends — Bob Fitzsimmons, Tony Canzoneri , Barney Ross and Armstrong.

The enhanced attention Benitez and Arguello received from fans and media delivered a powerful message to the rest of the sport: If one wants the same treatment, one must capture world titles in as many weight classes as humanly possible. That task became immeasurably easier with the arrival of the IBF and WBO (which were spawned from the ugly aftermaths of WBA conventions in 1983 and 1988 respectively); since Arguello’s win over Watt nearly 40 years ago, 51 fighters (male and female) have won widely recognized belts in three weight classes, 23 have done so in four, seven have earned titles in five, three in six divisions and two — Amanda Serrano and Manny Pacquiao — have done so in seven. If one counts The Ring featherweight title (and many do), Pacquiao is history’s only eight-division champion.

The sheer gaudiness of the numbers — and the ridiculous proliferation of secondary title belts — have greatly cheapened the value derived from chronic division-hopping. It happened so often that one had to strain to produce a measure of luster to the feat; for example, when former 122 and 126-pound king Carl Frampton challenged WBO junior lightweight titleholder Jamel Herring in April, one of the selling points was that “The Jackal” was attempting to become the first from Northern Ireland to win titles in three weight classes. Had he succeeded, he would have been justifiably feted back home, but in a global sense, becoming a three-division king is no longer what it used to be.

Although Adrien Broner can claim to be a four-division titlist — a designation that once was treasured by Arguello and Thomas Hearns, the man who eventually became the first to do so — the worth of his accomplishment is largely pooh-poohed in part because it is no longer unique. Leo Gamez, another four-division champion (105, 108, 112, 115), has yet to be elected into the IBHOF despite having been on the ballot for years. Would his fate have been better had he, and not Hearns, finished first in the race to four divisional belts?

In recent times, being named the pound-for-pound No. 1 was viewed as the ultimate status symbol — especially when fighters such as Julio Cesar Chavez, Pernell Whitaker, Roy Jones Jr., Floyd Mayweather and Manny Pacquiao held that crown for years on end — but because that designation is so heavily dependent on public opinion, which is rarely unanimous, the sport is in the process of returning to the classic definition of greatness: Undisputed champion.

There is a majesty that comes with being the one standing atop the mountain, for that person becomes the sole focus of those who want the crown for themselves, of the fans who follow the sport, and of writers and historians who chronicle it. While it is true that fighters over the past couple of decades have repeatedly expressed a desire to unify in post-fight interviews, such fights were rarely made. But thanks to those fighters occupying the top rungs of the sport in recent years — Terence Crawford, Vasiliy Lomachenko and Saul Alvarez — they not only talked the talk, they walked the walk and fought the fights. In fact, they demanded them.

Alvarez, The Ring’s No. 1 pound-for-pound fighter and the sport’s biggest non-heavyweight moneymaker, made clear that his primary goal is to become the undisputed champion at 168 before the end of the year, and his eighth-round corner retirement victory over Billy Joe Saunders has gotten him three-quarters of the way in the alphabet world and four-fifths of the way when one adds The Ring championship. He has declared, in no uncertain terms, that his next target is IBF counterpart Caleb Plant, and he will use his considerable influence to make that fight a reality. When WBO middleweight titlist Demetrius Andrade crashed the Alvarez-Saunders post-fight press conference and challenged Alvarez to fight him, “Canelo” made it clear — in two languages — that he would not take any detours.

Canelo Alvarez (left) is one step away from achieving undisputed status at 168 pounds after dethroning Billy Joe Saunders. Photo by Michelle Farsi/ Matchroom

If boxing is to complete the process of merging the past with the present in the most ideal manner — and, in the process, create a new definition of fistic greatness — another element must be encouraged and executed: The extinction of the one-or-two-fight per year schedule among the sport’s elite.

Given the huge purses the biggest stars earn, it’s easy to figure why fighters of recent vintage chose this approach. It’s the result of human nature and economics: Sugar Ray Robinson, Archie Moore and Harry Greb surely would have emulated today’s fighters had they earned millions of dollars every time they stepped between the ropes, and, conversely, today’s fighters would be forced to fight more than once or twice per year if they had been paid like Robinson, Moore and Greb were in their day. Most of us would prefer to take the path of least resistance if at all possible, and with professional boxers it goes a step further: They are taking the path of least pain.

Alvarez’s recent burst of activity proves that top-flight fighters can maintain a vigorous schedule against challenging opponents without suffering undue duress. His last three fights, all waged within a 140-day span, were against then-undefeated WBO titlist Callum Smith — regarded by many as the best in the weight class at the time — WBC mandatory Avni Yildirim (who Alvarez had to fight or else be stripped of his belt) and the previously unbeaten WBO titleholder Saunders, whose southpaw stance, mobility and ring intelligence prompted many to believe he could have posed a viable challenge. If the No. 1 pound-for-pound fighter in the sport can do it, why not the rest of the field?

In 1997, a prime Oscar De La Hoya — who entered the year as The Ring’s No. 2 pound-for-pound fighter — proclaimed that he would fight five times in a calendar year and he made good on that declaration by beating Miguel Angel Gonzalez in January, Pernell Whitaker in April, David Kamau in June, Hector Camacho in September and Wilfredo Rivera in December. Not surprisingly, “The Golden Boy” grabbed the top spot after defeating Whitaker and kept it for another two-and-a-half years. More recently, Tevin Farmer engaged in five world title fights between August 3, 2018 and July 27, 2019 while Emanuel Navarrete notched five successful title defenses between May 11, 2019 and February 22, 2020 — including two within 28 days, tying Wilfredo Gomez’s all-time divisional record for shortest turnaround between title bouts.

Oscar De La Hoya’s activity in 1997 is unheard of in today’s era. Photo from The Ring archive

Yes, ladies and gentlemen, it can be done and it has been done. All that is needed is the drive to make things happen and the cooperation of multiple parties to make it so.

If boxing wants to produce — and especially sustain — undisputed champions beyond a fight or two, and if it is to regain its rightful place as a big-time, perpetually prominent sport in the mainstream media on its merit and not on circus-like elements, two things must happen. First, the boxers must be willing to fight at least three times per year to keep their names in the headlines and to satisfy the demands of the various sanctioning bodies. And second, the sanctioning bodies must be more accommodating to the boxers in terms of dictating who their champions must fight next by declaring one agreed-upon mandatory challenger at a time.

Case in point: When then-WBO light heavyweight champion Dariusz Michalczewski defeated Virgil Hill to add the WBA and IBF belts in June 1997, the WBA arbitrarily stripped “The Tiger” for daring to display its belt alongside the hated WBO’s and the IBF forced him to surrender its belt when it demanded, via court order, that he defend against mandatory challenger William Guthrie a little more than a month after he fought Hill. As a result, Michalczewski remained the WBO titleholder and would go on to assemble a reign that numbered 23 defenses and lasted more than nine years.

Conversely, Cecilia Braekhus became an undisputed champion in September 2014 after adding Ivana Habazin’s IBF welterweight title to her other belts, and there was enough agreement among the sanctioning bodies regarding her challengers for “The First Lady” to record 10 successful defenses and produce a four-belt reign that lasted nearly six years.

Let’s say it again: It can be done and it has been done.

And it can be done again.

The surge in unification fights is proof that the sanctioning bodies are willing to cooperate with one another in terms of permitting these bouts, and given the huge sanctioning fees generated by big-money fights involving big-time champions, the ruling bodies can be motivated to transform the landscape if the right champions decide to accelerate their schedules as Alvarez has done in recent months. This system would never work under the “one-or-two-fight-per-year” era because of the obvious logjam that would result from chronic inactivity, but if enough elite fighters follow “Canelo’s” lead and step up their activity, and if the sanctioning bodies do what is necessary to cut through the red tape, a “new normal” could be created — a normal that would benefit everyone concerned as well as the sport of boxing. The void that is now being occupied by exhibitions involving stars of yesteryear and fights involving non-boxing celebrities would be filled.

The penultimate verse of the song “Everything Old Is New Again” certainly wasn’t talking about the fight game, but its message could be applied to the paradigm that is the process of emerging:

“Don’t throw the past away

You might need it some rainy day

Dreams can come true again

When everything old is new again.”

Ramirez vs. Taylor will be broadcast live on ESPN + in the U.S. and will stream live in the U.K. on FITE for £9.99 (coverage begins at 1:30 a.m. U.K. time).

*

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, West Virginia. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 19 writing awards, including two first-place awards, since 2011. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics” (available on Amazon) and the co-author of “Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers” (also available on Amazon). To contact Groves about a personalized autographed copy, use the email [email protected] or send him a message via Facebook or Twitter (@leegrovesboxing).

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE