George Foreman now realizes he is boxing’s January Man

It may be happenstance, but certain fighters sometimes tend to be associated with particular months. For Evander Holyfield, that month is November; not only did all three segments of the “Real Deal’s” classic trilogy with Riddick Bowe take place during that annual 30-day window, but so did his electrifying stoppage of Mike Tyson in their first fight, his avenging of a previous loss to Michael Moorer and his stirring comeback from a near-knockout scare against underdog Bert Cooper. And if all that weren’t enough, Holyfield made his pro debut in November of 1984, against Lionel Byarm.

December’s preferred poster boy is the late, great Archie Moore. “The Mongoose” was born and also died in the last month of the calendar year, which also is highlighted by his long-awaited crowning as light heavyweight champion on a points nod over Joey Maxim and his incredible 11th-round knockout of challenger Yvon Durelle in Montreal, a roller coaster ride in which he had to get up off the canvas four times, three in the first round.

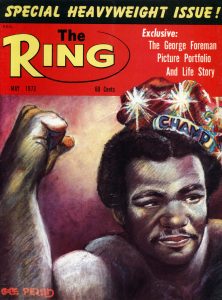

Following that train of thought, I sought to find out from George Foreman how he felt about his unofficial status as the fight game’s January Man, especially since his 72nd birthday occurred on Jan. 10. Interestingly, Big George told me he hadn’t given any previous scrutiny to a month otherwise chock-full of events of significance in his legendary career. In chronological order, Foreman ascended to the heavyweight championship for the first time by flooring favored titlist Joe Frazier six times en route to a second-round knockout on Jan. 22, 1973, in Kingston, Jamaica; overcame two knockdowns himself to pull out a fifth-round KO of Ron Lyle on Jan. 24, 1976 (The Ring’s Fight of the Year) in Las Vegas and, on Jan. 15, 1990, legitimized his comeback after a 10-year retirement from boxing by blasting out fellow power puncher Gerry Cooney in two rounds in Atlantic City.

Following that train of thought, I sought to find out from George Foreman how he felt about his unofficial status as the fight game’s January Man, especially since his 72nd birthday occurred on Jan. 10. Interestingly, Big George told me he hadn’t given any previous scrutiny to a month otherwise chock-full of events of significance in his legendary career. In chronological order, Foreman ascended to the heavyweight championship for the first time by flooring favored titlist Joe Frazier six times en route to a second-round knockout on Jan. 22, 1973, in Kingston, Jamaica; overcame two knockdowns himself to pull out a fifth-round KO of Ron Lyle on Jan. 24, 1976 (The Ring’s Fight of the Year) in Las Vegas and, on Jan. 15, 1990, legitimized his comeback after a 10-year retirement from boxing by blasting out fellow power puncher Gerry Cooney in two rounds in Atlantic City.

“Boy, January had some gifts for me, didn’t it?” said George (full disclosure: he furnished the foreword to my 2020 anthology, Championship Rounds) when he returned my call, as he always does. “You know, I hadn’t really thought about any of that until you mentioned it. But now that I am thinking of it, January has been especially good to me. Three of my children (daughter Michi and sons George III, a former pro heavyweight known as “Monk” who was 16-0 with 15 KOs, and George V, “who we call ‘Red’”) also were born in January. Those were happy times, for sure.”

So, George, let us take a stroll down memory lane for your recollections of the three January fights that are among your four most obvious signature victories in a 76-5 (68) Hall of Fame career, the other, of course, being the stunning, one-punch putaway of Michael Moorer in the 10th round on Nov. 5, 1994, in which you reclaimed the heavyweight crown, at age 45, nearly 22 years after you first won it. Oh, and if you don’t mind, please toss in a few musings about your just-as-momentous eight-round KO loss, as a huge favorite, to Muhammad Ali on Nov. 30, 1974, in the “Rumble in the Jungle” in Kinshasa, Zaire.

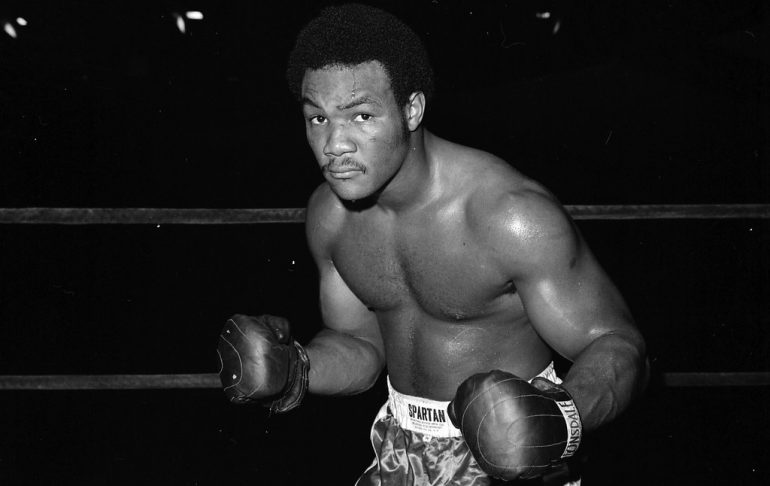

Despite coming into his first confrontation with Frazier (whom he also defeated, via fifth-round stoppage, on June 15, 1976) with a 37-0 record that included 34 very emphatic knockouts, Foreman was a 7-2 underdog against the left-hook specialist from Philadelphia, whom Big George now says is the only opponent he truly feared.

“(Dick) Sadler (Foreman’s manager) would always tell me, `This guy doesn’t have a chin,’ or `This other guy can’t punch,’” Foreman told me for a story I did six years ago and which also appeared in Championship Rounds. “He made it seem like everybody I fought had a big chink in his armor. But he and I both knew Frazier was as real as it got in boxing. You couldn’t talk bad about him because who would believe it? I was afraid, maybe because for once Sadler had nothing to say. He had too much respect for Joe Frazier to call him a bum or somebody who had no chance to beat me.

“All of a sudden I’m beating a guy like Joe Frazier, who could punch like he could and would never stop coming at you? I left there thinking, `Nobody can stand up to me.’ I just believed that if I caught anybody with a right uppercut or a left hook, he’d be gone. I could knock anybody out with either hand. It seemed impossible to me that I could lose.”

For this updating, nothing has changed in the way Foreman has come to view that fight, forever commemorated by ABC commentator Howard Cosell’s call of “Down goes Frazier! Down goes Frazier!” after the first of the six knockdowns.

Frazier-Foreman set the stage for epic heavyweight encounters.

“No, no way. Not with Joe Frazier,” he said of the six-pack of floorings that had Smokin’ Joe bouncing up and down off the canvas as if he were a dribbled basketball. “But I was accustomed to finishing guys off when I got them hurt, and I hurt Joe early. But you have to remember, everybody was fearful of Joe back then, me included. I wondered if he’d be the one to hurt me first. Did I expect what happened to happen the way it did? No way did I expect to knock Joe Frazier down that many times.”

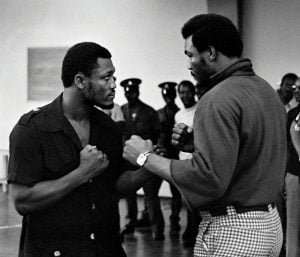

And if Foreman didn’t expect to do unto Muhammad Ali what he had done to Frazier, the same apparently can’t be said of Dick Sadler and cornerman Sandy Saddler, the two-time former featherweight champion, for the Africa showdown that demonstrated that sometimes an immovable object can withstand an unstoppable force.

Foreman said several mistakes were made in his preparations for Ali, not the least of which was his disinclination to study film of his fellow all-time great, or any other prospective opponent for that matter.

“I never watched any film of Muhammad Ali,” Foreman said. “When I came back after the 10-year layoff, before I accepted any fight I asked for film on the guy so I could study him. Why didn’t I do that with Muhammad? Because we were all so overconfident I would knock him out in two or three rounds. But Ali … man, he could take anything you gave him. You might be able to beat on him for 15 rounds, but he was nearly impossible to knock out. Nobody knocked Muhammad out, not even Joe Frazier. Joe knocked him down (in the 15th round of their first fight), but he didn’t knock him out.”

Anticipating another knockout victory as a matter of course proved to be a fateful miscalculation. “Sadler sent me out to put Ali away in the first round. I didn’t,” Foreman recalled. “He sent me out in the second round to do the same thing. I didn’t. Same deal in the third round, the fourth round. Sandy Saddler kept telling me, `You got him! You got him!’ I just tried to do what they were telling me to do.

“If I had to do it all over again, I’d do things differently. Even in the Joe Frazier fight, the first couple of minutes, I was out-boxing him. I could box better than a lot of people thought. But there were times when I got caught up in my own hype. After the third round with Muhammad, they should have had me trying to out-jab him, outwork him, all those things. If I had only stepped away from him and made him come to me, I could have lured him into a knockout punch rather than try to beat him into a knockout punch.”

A chastened Foreman didn’t have another fight that actually counted for the next 15 months, his only ring activity during that time an ill-conceived exhibition in Toronto where he took on five second- and third-tier heavyweights, one after the other. That hardly prepared him to swap haymakers with tough guy Lyle, an ex-con who arrived at the Caesars Palace Sports Pavilion convinced he could land the takeout shot against Foreman before Big George could scrape off any accumulated ring rust.

Lyle – whose record at that time was 31-3-1, with 22 KOs – came ever-so close to making his vision reality. He staggered Foreman with a big right late in the first round, announcing to the 4,100 on-site spectators and an ABC Wide World of Sports audience that he had ample firepower of his own. The two-way action was ratcheted way up in the fourth round, in which Foreman went down twice and Lyle once. At ringside, Cosell was yelping into his microphone, “This isn’t artistic, but it is slugging!”

Foreman was wobbled again by a right uppercut in round five, but Foreman fought back, again knocking down Lyle with a flurry of big shots with Lyle’s back against the turnbuckle in his own corner. Lyle pitched forward onto his face, where he was counted out by referee Charley Roth at the 2:28 mark. In addition to its Fight of the Year designation by The Ring, the “Bible of Boxing” also cited both the fourth and fifth as its co-Rounds of the Year.

“This fight could have gone either way,” Foreman admitted during his post-fight interview with Cosell. “When I was knocked down, I thought of Joe Louis. Joe Louis was knocked down in his career, and he got up. I figured if he could get up, so could I. So I got up and won.”

For a bout UPI boxing writer Dave Raffo had cleverly dubbed “Geezers at Caesars,” Foreman, who had turned 41 five days earlier, was putting his gradually increasing credibility on the line against Cooney, 33, a recovering alcoholic who was coming off a 2½-year retirement. It was, most agreed, a make-or-break bout for both big hitters, each of whom was to receive a $1 million purse. The winner, especially if the victory was accomplished with vintage blunt-force trauma, might be in line for more major paydays, specifically one against the biggest and most bankable star in the sport, Mike Tyson. The loser presumably would be consigned to shadowy irrelevance. And while Foreman sported a spiffy 64-2 record with 60 wins inside the distance, 18 of his 19 triumphs during his four years on the comeback trail were against what one skeptical writer (all right, so it was me) described as “never-weres, never-will-bes and overstuffed cruiserweights.”

There were out-of-the-ring story lines that also commanded attention, not the least of which was Cooney’s alliance with new trainer Gil Clancy, who had history with Foreman, having previously worked Big George’s corner for seven fights. Clancy said he had improved Cooney’s balance and had tightened up his most dangerous weapon, the left hook, thus making him less susceptible to counter rights.

“In the history of boxing, a good left hooker will always beat a good right-hand puncher,” Clancy pointed out. “The left hand is a lot closer to the opponent, for one thing. It doesn’t have to be thrown from as great a distance. If George Foreman starts winging those wide right hands, the way he does, and he gets caught with a left hook inside it, the fight could be over with one punch.”

Adding to his assertion that Cooney was new and improved, Clancy also noted that, while Foreman was “a terrific guy, I worked with him for seven fights, and there are no mysteries to George.”

Clancy was correct, in one respect. The fight, for all intents and purposes, was over with one punch. That punch was a left uppercut to the point of Cooney’s chin in the second round, resulting in the first of Gentleman Gerry’s two crash-landings. After Cooney arose on unsteady legs, Foreman, again the devastating finisher of his youth, delivered another crushing left uppercut followed by a clubbing right. This time, referee Joe Cortez didn’t bother with the formality of a count. The official ending came after an elapsed time of 1:57 in round two, but Cooney was out for nearly two full minutes before he could be helped onto a stool. He immediately announced another retirement, one that would stick.

What Cooney may not have known is that he had delivered the same kind of message to Foreman that Lyle had 14 years earlier. “Gerry Cooney hit harder than anybody I’ve been in with,” Foreman said at the time, describing the force of a Cooney first-round hook that landed on George’s fleshy upper arm. “He hit me so hard, even when I was covered up, the blow went through my arm to my chin. I was dizzy, but I couldn’t let a young guy know it. I said, `If I let him know he’s hurting me, this young guy – as far as I’m concerned, he’s still wet behind the ears – is going to tear me up.’

“So I just started loading up with power punches. No more sending out my jab. Gil Clancy had him prepared for my jab. I started to lead with the right hand and the fight started to change.”

It was a signal that the crusher of Clancy’s memory, the one who scarcely bothered to strategize or execute a fight plan, had morphed into, well, something of a sweet scientist. “Clancy, after the fight was over, asked me, `George, what are you doing?’” Foreman said for this story. “I said, `I’m just boxing.’ And he said, `No, no, no, you aren’t the same George. You come on like waves now.’ I’ll never forget that. He was saying that if you hit me, I’ll come right back at you, like waves on the ocean. What Clancy told me was the greatest compliment I ever got.”

Foreman (right) stops Lyle in five. Photo/ THE RING

The big question now is whether the septuagenarian January Man is the most devastating heavyweight puncher of all time, or just one of a fistful of contenders for that designation, a list that includes, among others, Tyson, Earnie Shavers, Rocky Marciano, Joe Louis, Max Baer and, most recently, Deontay Wilder.

“I never do think like that,” he replied. “But I did figure if I could just hit somebody, I’d knock him out. I never thought of it in terms of me being the hardest puncher, or somebody else being the hardest puncher.”

So while the man himself is somewhat noncommittal, take these endorsements from beyond the grave for what they’re worth.

Joe Frazier: “Ain’t no man ever hit me harder than George did. Ain’t no man ever hit anybody harder than George could hit ‘em.”

Muhammad Ali: “If you take any heavyweight you could think of, and multiply (their punching power) by two, that’s George Foreman.”

READ THE MARCH ISSUE OF THE RING FOR FREE VIA THE NEW APP NOW. SUBSCRIBE NOW TO ACCESS MORE THAN 10 YEARS OF BACK ISSUES.