Gray Matter: Errol Spence, Terence Crawford and the destruction of the welterweight division

In May 2017, Errol Spence Jr. came of age with a superb win over then-IBF welterweight titleholder Kell Brook. I was ringside that night at Bramall Lane soccer stadium in Sheffield, England, and the Texas-based lefty put on a brilliant display. Brook fought well, but Spence was superior in every department and scored a punishing 11th-round stoppage. “The Truth” has made five defenses since, added the WBC belt to his collection, and only a $275,000 Ferrari has gotten the better of him.

Just over one year later, Crawford, who had already claimed a plethora of belts at 135 and 140 pounds, made his welterweight debut against WBO titleholder Jeff Horn at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas. It was no-contest from start to finish. Horn was unable to land with anything significant and took a shellacking through the nine rounds that were contested. “Bud” has since made four successful title defenses.

However, immediately after Horn had been disposed of, fans and media began clamoring for a Spence-Crawford showdown. There had been talk of such a bout when both men were operating in different divisions, but Crawford’s impressive arrival at 147 pounds brought it closer to reality. Or so we thought. Two-and-a-half years down the line and Spence-Crawford remains firmly in the fantasy fight section and, speaking freely, that is an absolute disgrace and an afront to the welterweight division’s rich history.

Between November 1979 and September 1981, Sugar Ray Leonard fought Wilfred Benitez, Roberto Duran (twice) and Thomas Hearns. He won his first welterweight title from Benitez, lost it to Duran in his second defense, regained it in a direct rematch, then unified the entire division by stopping Hearns. In 22 months, Leonard, just 25 years old at the time, was already a legend and unanimously lauded as an all-time great.

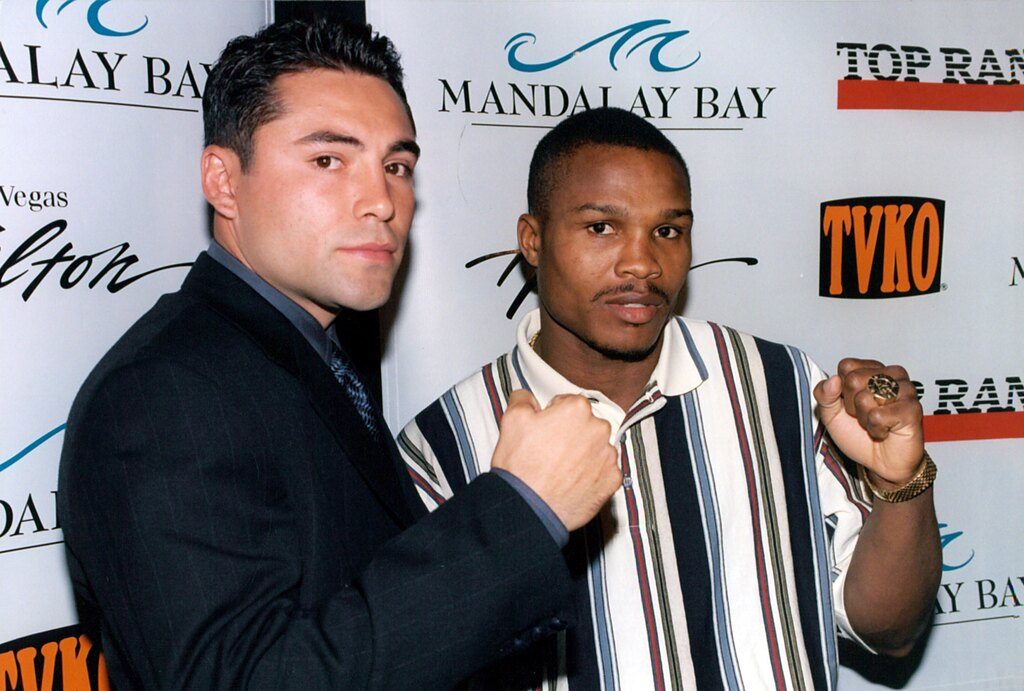

Oscar De La Hoya and Ike Quartey squared off in 1999. Photo from The Ring archive

Like Crawford, Oscar De La Hoya hit welterweight after capturing world titles in the lower weight classes. The 1992 Olympic champion always knew that he would come into his own at welterweight and that his legacy hinged upon superfights within that division. “The Golden Boy” defeated Pernell Whitaker, in his 1997 welterweight debut; Ike Quartey, who was unbeaten; and he lost close decisions to Felix Trinidad and Shane Mosley. De La Hoya’s quest for greatness at welterweight lasted a little over three years.

Look at the names and numbers above and you can see just how shambolic the unending Spence-Crawford saga is.

“Oh, but they’re fighting on different networks!” Who cares? In order to get Leonard and Duran in the same ring, Bob Arum and Don King had to work together when the hall-of-fame promoters had more dislike for each other than the fighters. And that is no exaggeration. Go back to 1980 via time machine and ask King and Arum to appear together in a 7-Up commercial. It’ll be a case of who tells you to “f__k off” first. Bottom line, Leonard-Duran needed to happen and it did – twice. And guess what? When another welterweight collision had to happen two decades later, it was Arum and King who came together to make De La Hoya-Trinidad.

Ironically, it’s Arum who promotes Crawford, although that relationship appears to be on shaky ground. The Top Rank boss recently stated that he is no longer willing to lose money on Crawford, attributing the fighter’s unwillingness to self-promote as the reason why he can’t transform a 37-0 unbeaten record and state-of-the-art skills into comparable dollars. Crawford argues that Arum is the promoter and it’s his job to promote. That sounds good, but it’s total crap. Muhammad Ali wrote the book on self-promotion over half-a-century ago and it’s been followed many times since. Look no further than reigning heavyweight champion Tyson Fury. The enigmatic Englishman knows that his ring performances aren’t enough to secure massive paydays, so he perfumes the pre-fight ballyhoo with his own unique brand of showmanship. Love him or hate him, fans and – crucially – a lot of non-fans want to see Fury fight. It might seem unfair, but unless you have the knockout power of a Mike Tyson, the blazing speed and explosiveness of a peak Manny Pacquiao, or the movie-star looks of an Oscar De La Hoya, then you must put the work in outside of the ring. Spence is no hotshot in this regard himself, which is why the Crawford fight is not the guaranteed financial bonanza that the rival champions perhaps expect.

That’s right, boys, you would be doing this one for legacy. What a bummer! Just because you have world title belts, pound-for-pound talent and the opponent to match, that doesn’t mean you can expect Mayweather-Pacquiao paydays or anything remotely close. If that was the case, Juan Francisco Estrada and Roman Gonzalez would be making a hell of a lot more money than they’ll be getting for their March rematch. And those guys buckled up and ran at each other to make that fight.

Money is a double-edged sword in modern day boxing. On one side, it’s great to see elite-level fighters cashing in after years of sacrifice and dedication. On the other side, many of these fighters have been spoiled and that has created an era of self-entitled prima donnas. Crawford and Spence, and many others, have been making life-changing money without squaring off in the fight that fans want to see. That approach wasn’t always possible.

George Foreman and Muhammad Ali faced off in arguably the most famous fight in boxing history. Photos from The Ring archive

Two-time heavyweight champion George Foreman once explained the past and the present to me as it related to his own division. “The thing that’s really changed is there’s money available for heavyweight champions to fight just about anyone,” he said. “In the 70s, you only made big money by taking on a world champion who put bread on the table. You had to face great fighters. I defended the championship against Ali, and we were guaranteed $5 million apiece. I wasn’t gonna turn that down. Ali had just come off big fights against Ken Norton and Joe Frazier, but he didn’t make that kind of money with them. He got the payday in the title fight against me. Nowadays, a so-called champion can fight anyone and still make big money.”

It’s tough to argue.

Leonard’s guarantee in the first fight with Hearns was $8 million. Five month later, he would make the only defense of his undisputed welterweight championship, against the unknown Bruce Finch, for a guaranteed purse of $1.3 million. This was Leonard coming off arguably the finest win of his career and he accepted over six times less money. In November, Crawford made $4 million for defeating Kell Brook, an 8-to-1 underdog, whereas Spence was guaranteed $8 million for outpointing Danny Garcia, who was a 3½-to-1 underdog. Just for fun, let’s say that Crawford and Spence want six times more money than they got for their most recent fights to face each other. That would give Crawford a $24 million guarantee and Spence would be on double that.

Yes, you’re right, that isn’t happening, and until Crawford and Spence take their focus off A-sides, B-sides, percentages and purse splits, neither is the fight. The sport needs its elite-level players to be realistic in terms of financial demands, particularly in a world that is being ravaged by a pandemic. Now would be the perfect time to duplicate past champions and chase authentic greatness and without that approach, neither Crawford or Spence can be compared to Leonard or De La Hoya in historical terms.

“There were so many great fighters,” Leonard once told me when I asked about his glory days. “I try to tell boxing fans today, but they don’t really get it. It must be like boxing fans from the 50s and the 60s trying to explain to us what it was like back then. You can never express just how great the fighters were in my era. I guess that’s the beauty of it.

“I never even thought about legacy until it became a question. Reporters would say, ‘Ray, this is for your legacy’ and ‘This is what you’ll be remembered for’. If you beat Duran, you’ll be this. If you beat (Marvelous Marvin) Hagler, you’ll be that. If you fight this way, you’ll be admired. Okay, you got knocked down, but you got back up. Those comments made me stronger and made me understand what I was fighting for.”

No, you wouldn’t have caught a peak version of Leonard chasing down a 42-year-old Pacquiao for a payday when there were bigger fish to fry. Sugar Ray would have taken on Crawford and Spence in a heartbeat and probably back-to-back, too.

Tom Gray is Associate Editor for Ring Magazine. Follow him on Twitter: @Tom_Gray_Boxing

READ THE LATEST ISSUE OF THE RING FOR FREE VIA THE NEW APP NOW. SUBSCRIBE NOW TO ACCESS MORE THAN 10 YEARS OF BACK ISSUES.