No, Bernard Hopkins hasn’t forgotten his first time

They say you never forget your first time.

There have been a lot of first times for Bernard Hopkins in both his boxing and non-boxing personas, and he is convinced his memories of all those introductory moments, good and bad, have played a part in who the 55-year-old legend is today. Hopkins, voted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame’s Class of 2020, his first year of eligibility, is a human mosaic, a veritable patchwork of rousing successes and epic mistakes. Decades of self-reflection have convinced him all those personal highs and lows were, in their own way, building blocks upon which his highly improbable life’s journey has been crafted.

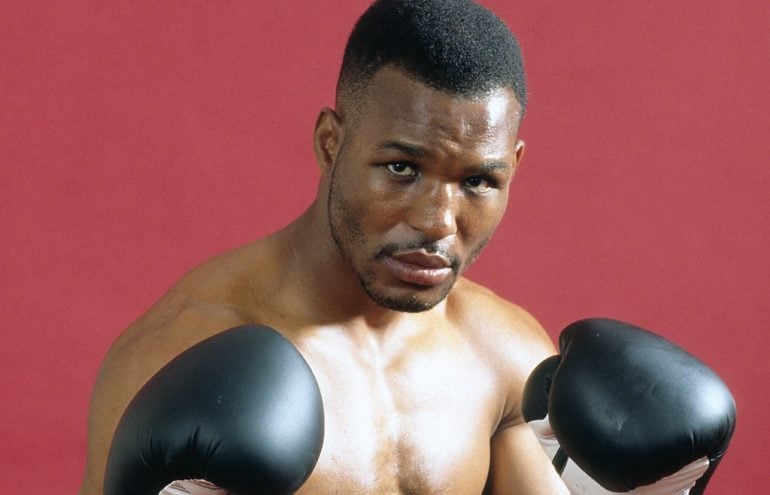

Clinton Mitchell

One of the more important firsts for Hopkins came 32 years ago, on October 11, 1988, when the most unlikely of the fight game’s rags-to-riches tales was birthed in defeat and disappointment. Few boxing buffs had even the slightest inkling as to who the then-23-year-old ex-con from Philadelphia was when he entered the ring at Atlantic City’s Resorts International for a four-round light heavyweight bout against a former New York Golden Gloves champion named Clinton Mitchell. Hopkins, who would go on to become the oldest man ever to win a widely recognized world champion, and whose career as an active fighter would last a jaw-dropping 29 years, was a likely designated victim – an opponent, in pugilistic vernacular – and he was expected to lose, which he did. The four-round majority decision for Mitchell served not only to knock much of the cockiness out of Hopkins, whose bluster regarding his boxing abilities was clearly restored during his rise to and subsequent reigns at middleweight and light heavyweight, it sent him into a funk which saw him refrain from fighting again for 16 months.

So, did the setback to Mitchell do that much damage B-Hop’s confidence as a fighter?

“You know it did,” he told The Ring. “That’s why I was off as long as I was. I was crushed, man.”

At that point, Hopkins could have been just another one-and-done fighter, except for the fact that he hadn’t really performed badly against the highly regarded Mitchell and, even more importantly, there was another battle, outside the ropes, he knew he would have to wage and win within himself regardless of whether he ever tugged on another pair of padded gloves.

“I couldn’t see Shirley Mae Hopkins suffer any more,” Hopkins said of the pain his mother, who had borne seven other children, felt from not only from his 56-month incarceration as prisoner Y4145, but the murder of his younger brother Michael, another senseless victim of the kind of violence that have turned America’s inner cities into something akin to war zones. B-Hop, who began his sentence a few months before Michael was killed, learned of the latest family tragedy during one of his allowable phone calls home. Through the prison grapevine Hopkins later found out that the man convicted of killing Michael would also be going into the general population of the same penal institution, putting them on an inevitable collision course that almost certainly would have left one of them dead.

“When this guy came in, my reputation was on the line,” Hopkins said of the revenge he would have had to seek given the harsh protocols of prison life. “You kill my brother, you come into my prison and I do nothing, what does that say to the other inmates about me? If I don’t kill him, my credibility is shot. I’m a marked man. I’m a dead man.”

Bernard Hopkins under the watchful eye of Bouie Fisher.

But Hopkins’ quest for vengeance was thwarted when he was transferred from now-closed Holmesburg Prison to Graterford State Correctional Institution, where he came under the influence of an older inmate, Michael “Smokey” Wilson, who became his friend, mentor and adviser.

“I’m just glad Bernard didn’t kill no one,” Wilson, who served 46 years on a murder conviction and, since gaining his freedom in 2017, has again become a part of Hopkins’ inner circle, told me several years ago. “To me, he’s the epitome of what rehabilitation is, or is supposed to be. He never came back. He showed what, given the opportunity, an individual – any individual – can do.”

Wilson’s influence and the desire not to give his mom cause to cry again aside, the post-Mitchell Hopkins still was burdened by a felony conviction and seemingly few options if boxing didn’t work out. But by then he had seen enough of the wrong side of life to know that what might seem to be the easy way is almost never the right way.

“I went home after that fight and didn’t know what to do, other than I didn’t want to get into the JBM, the Junior Black Mafia,” Hopkins recalled. “I didn’t want to get into the drug trade. Doing any of that was only going to get me put behind bars again, and I had vowed to myself I would never let that happen. Look, I easily could have taken a kilo of cocaine and flipped it because I knew all the people who were doing that. They were the people I grew up with! When I took my time off from boxing, that was the challenge for me, not to get into any more criminal behavior.”

What Hopkins did get into was long hours, physically taxing and, yes, low-paying labor as a roofer. “I had to get up at 4:30 in the morning to go to the work site and not leave until a quarter to six in the afternoon,” he said. “Oh, man, talk about hard work. I don’t care what season it is, that’s hard work. I remember thinking, `I can’t do this for the rest of my life.’”

It was on one of those roofs that Hopkins every now and then would do some shadowboxing moves and tell his fellow workers that he’d be a boxing champion someday. To which one of his co-workers, Steve Traitz Jr., said, `Aw, man, you ain’t gonna be shit.’ To settle the matter of whose vision of the future was the more likely, the two men traipsed off to Slim Jim Robinson’s gym where, Hopkins said, “I damn near knocked Steve’s head off.” An impressed Traitz, who also tried his hand at boxing, agreed, saying, “This kid actually might have something.”

Roy Jones (left) against Bernard Hopkins in 1993. Photo from The Ring archive

So it was back to boxing, and this time Hopkins demonstrated that he was more, much more, than fodder to be sacrificed to prospects with presumably brighter futures. Hopkins reeled off 22 straight victories, including 16 knockouts, en route to his first shot at a world title, and his first matchup with Roy Jones Jr. He lost, but not very much thereafter in finishing with a 55-8-2 record, with 32 KOs. Hopkins’ 20 middleweight title defenses were a division high, since matched by Gennadiy Golovkin, and his 12-round, unanimous decision over Ring Magazine/WBC light heavyweight champ Jean Pascal on May 21, 2011, in Montreal made him, at 46, the oldest man ever to claim a widely recognized world championship, displacing George Foreman for that distinction.

There isn’t really that much for Hopkins to regret, except maybe for one thing: he never got the chance to settle the score with Mitchell.

“I did some research four or five years ago and found out that he had passed away,” Hopkins said. “I got that information from one of his siblings, a sister. She was shocked that I took the time to seek her out and talk to her about her brother. You know, he was supposed to become what I became. He fell short of that, but it wasn’t his fault. He had some sort of rare disease and has been dead for over 15 years.”

Actually, the disease wasn’t all that rare, according to veteran matchmaker Ron Katz, who claims responsibility for putting Hopkins together with Mitchell. “He became a diabetic, I’m 99.99% sure of that, and if definitely had an effect on his career,” Katz said of the Brooklyn native who took seven years off from the ring after getting the nod over Hopkins.

Katz, who has made hundreds if not thousands of matches during his own illustrious career, has a keen enough memory that he claims to remember details of Mitchell-Hopkins, which was on the undercard of a show headlined by welterweight John Wesley Meekins’ 10-round majority decision over Saoul Mamby.

“It was a very, very close fight,” Katz recalled. “I think the Atlantic City paper had it a draw. Hopkins definitely showed some ability, and toughness.

“You know, I’m the answer to a trivia question. I got Bernard licked in his first pro fight and his last fight (by eighth-round knockout vs. Joe Smith Jr. on December 17, 2016, in Inglewood, California). I put together both those fights.”

SUBSCRIBE NOW (CLICK HERE - JUST $1.99 PER MONTH) TO READ THE LATEST ISSUE