Marvelous Marvin Hagler-Alan Minter: Victory violated 40 years on

Forty years ago today, Marvelous Marvin Hagler confirmed the veracity of his moniker with a vicious yet clinical demolition of Alan Minter to seize the undisputed middleweight championship. Unfortunately for him and the approximately two dozen Hagler partisans inside London’s Wembley Arena, Hagler was given precious little time to celebrate the end of what had been an arduous, years-long journey to the top of the middleweight mountain, for moments after dropping to his knees and bowing his head in thanksgiving, the first of what would be several beer bottles crashed into the ring. Their heavy thumps indicated many were still filled with liquid, and some of them hit their targets, including a bottle that struck Goody Petronelli, Hagler’s chief second, as well as a beer can and a bottle that hit BBC broadcaster Harry Carpenter.

The blitzkrieg of bottles prompted a group of ringsiders to surround Hagler and guide him toward several helmeted bobbies positioned just outside the ring. The shield they formed held up just long enough to hustle the Americans into a tunnel that led straight into police headquarters. Hagler was long gone from ringside by the time he was officially proclaimed the new champion.

Hagler later stated he felt more like a thief than a newly crowned world champion, but it was he who was robbed — robbed of his one and only chance to fully experience the initial flush of excitement his mountaintop moment earned him.

Hagler celebrates before things turn very nasty. Photo from The Ring archive

Every child who aspires to become great silently projects himself to that culminating slice in time when the thousands of hours of hard work finally bears fruit. It is a dream that is lived countless times inside the minds of numberless hopefuls but a precious few ever get to experience it before thousands of witnesses. The explosive mixture of elation, elevation and accomplishment only lasts a few seconds, but that wondrous feeling creates an imprint that lasts a lifetime. But the actions of a furious few cut short that process for Hagler, and over the next six-and-a-half years he used that bitterness to craft one of history’s greatest middleweight championship reigns. Even to this day, however, the scenes produced by that horrid aftermath remain seared into the minds of Hagler, his family, his team, and the millions who either saw it live in the arena or on worldwide television. One of those millions was a 15-year-old from Friendly, West Virginia who watched the fight — and the ensuing spectacle — on ABC.

For that teenager — and for everyone else old enough to have viewed it as it happened — the images of that fight, and that era, remain vivid. As you will read, boxing during that time was different in some ways yet similar in others.

On September 27, 1980 boxing’s administrative structure at the world level was far simpler. The WBA and WBC were the only two entities that awarded widely recognized world championships, and, unlike today, only one person at a time reigned as its champion. Any thoughts of creating multi-tiered hierarchies of “super,” “regular,” “interim,” “gold,” or “emeritus” titlists were decades away, and Minter, who began this day as the titleholder, was the only fighter in the sport who owned both the WBA and WBC championships.

In fact, the middleweight title had been undisputed since June 26, 1976 after WBA titlist Carlos Monzon outpointed WBC counterpart Rodrigo Valdes in Monaco to become the one and only champion for the second time (he was stripped of the WBC share he had held since November 1970 in 1974 after refusing to meet Valdes at the time of the sanctioning body’s choosing). He retained the belts against Valdes in what would be his final fight 13 months later but instead of splitting the belts upon Monzon’s retirement, the WBA and WBC agreed that a match between Valdes and Bennie Briscoe should be for both championships — an almost unthinkable notion in today’s world. Valdes outpointed Briscoe over 15 rounds to become Monzon’s successor on November 5, 1977 in Lombardy, Italy but was dethroned in his first defense against Argentina’s Hugo Corro the following April in San Remo, Italy. Corro notched successful defenses against Ronnie Harris (split W 15) and Valdes (W 15) before being toppled by Vito Antuofermo June 30, 1979 in Monte Carlo.

Following Antuofermo’s triumph, Hagler, who had been calling out Corro by name in post-fight interviews and in various boxing publications, turned his attention to “Vito the Mosquito,” and thanks to his frequent TV appearances — and impressive ring performances — Hagler was deemed Antuofermo’s mandatory challenger. To his credit, Antuofermo bypassed any “voluntary” defenses and immediately signed to fight Hagler, who was installed as a 4-1 favorite to win the championship November 30, 1979 at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas.

Hagler’s road to his first championship opportunity was pockmarked with adversities, both in and out of the ring. A native of Newark, N.J., Hagler and his family moved to Brockton, Mass. because part of the $11 million in property damage resulting from the 1967 Newark Riots included the building that housed the Haglers. Two years later, a 14-year-old Hagler — masquerading as a 16-year-old — began boxing in amateur tournaments, and his skills earned him numerous championships, including the 1973 National AAU and 1973 National Golden Gloves titles. Soon after that, Hagler turned pro and went 25-0-1 (19 knockouts) before traveling to Philadelphia to take on Bobby “Boogaloo” Watts and Willie “The Worm” Monroe, two members of what Hagler called “The Iron.” Hagler dropped a disputed majority decision to Watts in January 1976, then, two fights later, comprehensively lost to Monroe over 10 rounds. Entering the Antuofermo match, Hagler had won 20 in a row — 18 by KO — and was expected to dominate the shorter, squatty champion.

Antuofermo was lucky to retain the title on a disputed draw with Hagler in 1979. Photo from The Ring archive

The fight followed form in the early rounds, but after the midway point Antuofermo — who was suffering from bronchitis — somehow mustered enough energy to stage a robust rally. While Duane Ford’s 145-141 card for Hagler reflected conventional wisdom, he was negated by Dalby Shirley’s 144-142 score for Antuofermo. In the end, Hal Miller overruled both of them as his card read 143-143, a draw which meant the Brooklyn-based Italian would remain champion.

In other words, a disputed decision allowed Antuofermo to stay undisputed.

The result only added to Hagler’s fury, and it ultimately served as the foundation for how he approached the remainder of his career.

“All this does is add to the bitterness in me,” Hagler said. “But I’m going to keep it there because it will make me even meaner and tougher and inspire me to work even harder so the next time I’ll come out as the champion.”

While Antuofermo indicated a willingness to give Hagler an immediate rematch, he was ordered to face Minter next.

Unlike the switch-hitting Hagler, Minter did all of his fighting from the southpaw stance, and his long-range, jab-heavy style piled up points as well as victories. After the native of Penge, Bromley, Kent, England won the 1971 ABA middleweight title, Minter earned a spot on Great Britain’s 1972 Olympic team. He advanced to the medal round thanks to wins over Reginald Ford of Guyana (KO 2), the Soviet Union’s Valery Tregubov (W 3) and Algeria’s Loucif Hamani (W 3), but while many observers thought he did enough to defeat West Germany’s Dieter Kottysch, the 3-2 decision for the home country fighter denied him his chance to compete for the Olympic championship. While Minter settled for bronze, Kottysch went on to win gold with another 3-2 verdict against Poland’s Wieslaw Rudkowski, making Kottysch the only German boxer to complete the tournament unscathed — at least officially.

Minter turned pro with a sixth-round TKO over 35-fight veteran Maurice Thomas 53 days after his Olympic disappointment and he rolled to an 11-0 (8 KOs) record before meeting journeyman Don McMillan at London’s historic Royal Albert Hall. Minter had his way with McMillan for most of the contest — he was well ahead on points thanks to the three knockdowns he scored — but the fight was stopped in Round 8 due to a gash on Minter’s right eyebrow. The result was a TKO loss, the first of what would become many due to his sensitive scar tissue.

The McMillan loss ignited a turbulent period in which Minter went 3-3 with one no-contest. All the losses were on cuts, including back-to-back defeats to Jan Magdziarz in fights that were held just 42 days apart, far too short a gap for the gash over Minter’s right eye suffered in fight one to properly heal. Following an eight-round points win over Tony Byrne, Minter’s brows failed him yet again, this time against 24-22-2 Bronx product Ricky Ortiz, and he followed with a fourth-round no-contest against Magdziarz in which referee Harry Gibbs disqualified both boxers for, as Boxrec put it, “not giving of their best.”

Despite the hardships, disappointments and struggles, Minter soldiered on and achieved sustained success. Minter won his next 13 fights, a stretch that included two 15-round decisions over Kevin Finnegan, the first to capture the vacant British middleweight title and the second to retain it. He then added wins over onetime world title challenger Tony Licata (KO 6) and 1972 Olympic gold medalist Sugar Ray Seales (KO 5) to certify his elevated standing. But the troubles regarding his facial tissues resurfaced as he lost on cuts to Ronnie Harris (KO 8), then Gratien Tonna (KO 8) thanks to a vertical slice on his forehead. Sandwiched between those bouts was a 10-round decision over the legendary Emile Griffith, a result that prompted the 39-year-old future Hall of Famer to announce his retirement.

Just 47 days after losing to Tonna, Minter commenced his definitive drive toward his championship opportunity by beating Finnegan for the third time over 15 rounds to retain his British championship, the first of what would be eight straight victories. This string included triumphs over Tonna (KO 6), Doug Demmings (W 10) and Italy’s Angelo Jacopucci, a bittersweet victory if ever there was one. That’s because while Minter became the new European champion, Jacopucci died of his injuries three days after the bout, which, according to the New York Times, led to a second-degree manslaughter conviction against ringside physician Ezio Pimpinelli that resulted in an eight-month jail sentence and a $14,000 payment to Jacopucci’s widow.

The outcome almost produced another result: The end of Minter’s boxing career.

“I’m not a killer; I was there to win, not to injure,” Minter said in an article written by Steve Bunce in The Independent. “I sat down after I found out about his death and I asked myself about fighting on. I thought, it was him, but it could have been me. I knew then I would continue. There is one thing — and I’m not bragging — but I wanted Jacopucci’s children to be able to say that their dad lost to a champion and not just some mug.”

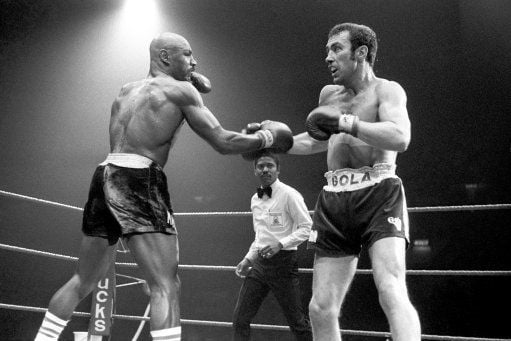

Minter looks to score against Vito Antuofermo in the first of their two undisputed middleweight title fights. Photo from The Ring archive

The Demmings victory led to the title fight against Antuofermo March 16, 1980 at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas. The local bookmakers installed Minter as a 2-to-1 favorite, probably because of the unpopularity of the champion’s draw against Hagler, but Minter — cheered on by more than 1,000 countrymen who crossed the pond — outboxed Antuofermo over the first four rounds. Antuofermo appeared to find his timing starting in the fifth and, from there, the bout was fought at a torrid pace with each man enjoying slices of success. Given both men’s propensity to cut, Antuofermo versus Minter was expected to be a bloodbath, but while each man suffered cuts in Round 12, both injuries were well controlled by their respective corners.

Late in Round 14, Antuofermo scored the bout’s only knockdown — and the first of Minter’s pro career — with a snappy hook to the chin. In the end, however, the tumble had no bearing on the final result: A split decision for the winner….and new champion.

Most observers believed the fight to be closely contested, and the scorecards of Chuck Minker (144-141 Minter) and Ladislao Sanchez (145-143 Antuofermo) reflected that conventional wisdom. But the scorecard of England’s Roland Dakin — 149-137 for Minter — was heavily criticized. When asked to explain his scoring, Dakin reportedly replied that he was able to count the number of punches landed by each man and found that Minter, in his view, had demonstrated an extreme level of superiority.

Few, however, bought that story, and that scorecard was used to justify an immediate rematch, this time in Minter’s backyard of London. Their second meeting on June 28, 1980 was a bloodbath — albeit a one-sided one — as a succession of needle-sharp blows opened a cut over the former champion’s right eye a little more than two minutes into the fight. While Antuofermo continued to fight bravely, his cause was rendered all but hopeless from that point onward as a crimson-free Minter opened a gash over the left orb in Round 2, then skillfully picked away at the wounds until Antuofermo’s corner stopped the fight between rounds eight and nine.

While Minter and Antuofermo were engaged in their back-to-back title fights, Hagler continued to build his case as the “next man up” by crushing Loucif Hamani in two rounds in February, avenging his previous loss to Watts with a vicious two-round knockout in April and out-pointing veteran Marcos Geraldo over 10 rounds in May. By beating the Mexican middleweight champion, Hagler was now poised to take on the world middleweight champion. This time, however, he would have to do so in heavily pro-Minter territory — London’s venerable Wembley Arena, the site of Minter-Antuofermo II.

For a while, however, there were questions as to whether Minter’s titles would be at stake. At the weigh-in — staged inside the ring at Wembley just hours before the match — Hagler initially scaled a half-pound over the 160-pound limit, then, after removing his underwear, three ounces over. The challenger was given two hours to shed the excess poundage, but Hagler needed only 35 minutes to hit 160.

“I weighed myself in this morning and I was 160,” Hagler told Carpenter. “I was surprised at the difference on this scale (in the ring). It don’t surprise me; I’ve been through this before and everything’s experience for this fight. I’m just going to take it out on Minter now.”

For the record, Minter weighed 159.75.

Although Hagler was viewed as the favorite in America, the British bookmakers viewed it as a much closer contest: Minter was a 4-5 choice while Hagler was an even-money proposition.

Minter became a national hero upon winning the championship, and the atmosphere before the Antuofermo rematch oozed with patriotic pride. But the pre-fight buildup for Minter-Hagler featured a far more sinister element that would play a large role in the fight’s aftermath — race-based rhetoric.

According to Sports Illustrated’s Clive Gammon, the hard feelings between the combatants was sparked by an incident that took place in the ring shortly before Hagler’s challenge of Antuofermo. After the dignitaries were introduced, Hagler allegedly refused to shake hands with Minter. The memory of that reported rudeness moved Minter, now the champion, to declare before a group of reporters that “I am not letting any black man take the title from me.” Adding to the pre-fight tension was Finnegan’s story that Hagler, in refusing a handshake, said “I don’t touch white flesh.”

Both parties attempted the lower the temperature a bit; Minter said the actual quote was “I am not letting that black man take the title from me” while Hagler said he refused to shake Minter’s hand because he never extended that courtesy to any potential future opponent regardless of skin color, but would be willing to do so after the fight. But their efforts proved futile, for on fight night the throng that gathered inside Wembley Arena was boisterous, drunken and, for some, fueled by an ugliness of spirit.

The pre-fight pomp and circumstance followed the same pattern as was practiced before Minter-Antuofermo II, right down to the trumpet fanfares given to champion and challenger but while Antuofermo’s arrival was greeted with indifference, Hagler’s was showered with boos. The throng chanted Minter’s surname even before the fighter emerged from his dressing room, and once he did, Carpenter marveled at “the great crescendo of sound” that marked his arrival. Union Jacks were everywhere in the Minter entourage; Minter even wore a pair of flag-themed underpants at the weigh-in while the two flag bearers wore suits bearing the tell-tale pattern.

While most in the crowd respectfully listened to the “Star Spangled Banner,” some elements emitted whistles and boos, but the playing of “God Save the Queen” was accompanied by the thunder of 10,000 voices — including that of the reigning middleweight champion.

Photo by S&G and Barratts/EMPICS Sport

To the surprise of many Minter, the points-oriented long-range boxer, began the fight by holding his ground and moving forward behind his jab while the bobbing Hagler patiently probed for openings. A sharp left following two soft jabs forced Hagler to take a step back and caused the crowd to roar in appreciation, but Hagler responded moments later with his own right to the face following a missed left. After the action returned to ring center, Hagler connected with several spearing jabs that set up a clean right hook to the face.

It didn’t take long for Hagler to prove he could land punches with ease, and it took him less than 90 seconds to create the first wound, a cut under Minter’s left eye. The injury forced Minter to return to long range but Hagler, a shorter man blessed with a mammoth 75-inch reach, repeatedly drilled jabs into the champion’s face while expertly blocking and slipping Minter’s return fire. By the time Minter returned to his corner his left eye had picked up additional damage in the form of redness and swelling.

Told by his corner to “settle down,” Minter attempted to comply at the start of Round 2 by focusing on the jab. The composed Hagler countered Minter’s jabs with his own, then crossed a left over the top. Moments later, Hagler answered a missed Minter jab with a cross-hook that created a cascade of crimson from the champion’s nose as well as a tsunami of anger. As if a switch had been flipped, Minter’s previously blank face curled into a snarl as he beckoned Hagler to “come on” with his right glove and he backed up his tough non-verbal cues by recklessly charging at the challenger. Hagler responded with a heavy right-left that snapped Minter’s head and soon blood was pouring from Minter’s nose and his right orb now had a slice underneath it. The crowd tried to lift the champion’s spirits by chanting his name but their sonic support could do nothing to reverse an increasingly negative tide.

Minter tried his best to turn that tide himself, and in the round’s final moments he managed to pin Hagler to the neutral corner pad thanks to a brief burst of power shots, but a closing left uppercut-right hook to the face closed out what had been a superlative round for Hagler.

The challenger’s excellent form continued in the third as his right hand connected as if magnetized to Minter’s face. A leaping right hook drove Minter backward and as he tried to slap on a clinch the challenger landed a scything uppercut. A brief mill on the inside was broken with another right-left that knocked out Minter’s mouthpiece.

The degree of Minter’s duress increased exponentially with each passing second and his facial expression communicated that reality. The championship for which he worked so hard was slipping away in front of thousands of supporters and the hostile transfer of power appeared mere seconds away. Conversely, Hagler’s focus was steely, his punches were powerful, and his emotions were firmly under control.

Another massive right hook buckled Minter’s legs and caused him to totter toward the neutral corner pad, and for the first time in the fight Hagler went for the kill as he overwhelmed the champion with a fusillade of blows.

With his face now covered in red, Berrocal stepped in and asked for Minter’s injuries to be examined. Before that could take place, Minter’s cut man asked the Panamanian referee to stop the fight, and at 1:45 of Round 3 Marvelous Marvin Hagler was declared the new undisputed middleweight champion of the world.

With a crouching Goody Petronelli to his right and Berrocal to his left gripping his upraised arm, a kneeling Hagler began the task of processing this life-changing moment. Unfortunately for Hagler — and for history — he was granted just seven seconds.

That’s because the crowd that included members of the National Front — Britain’s equivalent of the Ku Klux Klan — and the sight of Hagler’s triumph was too much for them to swallow. A hailstorm of debris was hurled into the ring and a collection of authorized ringsiders formed an impromptu tent around Hagler. The bobbies then shepherded the new champion and his team to safety. Amazingly, Minter remained in the ring to receive treatment for his injuries.

Moments after Minter departed, ring announcer Bernard Sullivan spoke for most of the world when he sternly rebuked the rioters.

“This scene around the ring could have killed somebody,” he declared. “I say that those involved should be ashamed of themselves! And no matter what goes on, that was disgusting!” The British Minister of Sport agreed as he called the incident a “disgrace,” and promoter Mickey Duff later issued a public apology to Hagler on behalf of British boxing.

But while Hagler’s in-ring celebration was woefully cut short, he fully savored his accomplishment once he reached the dressing room.

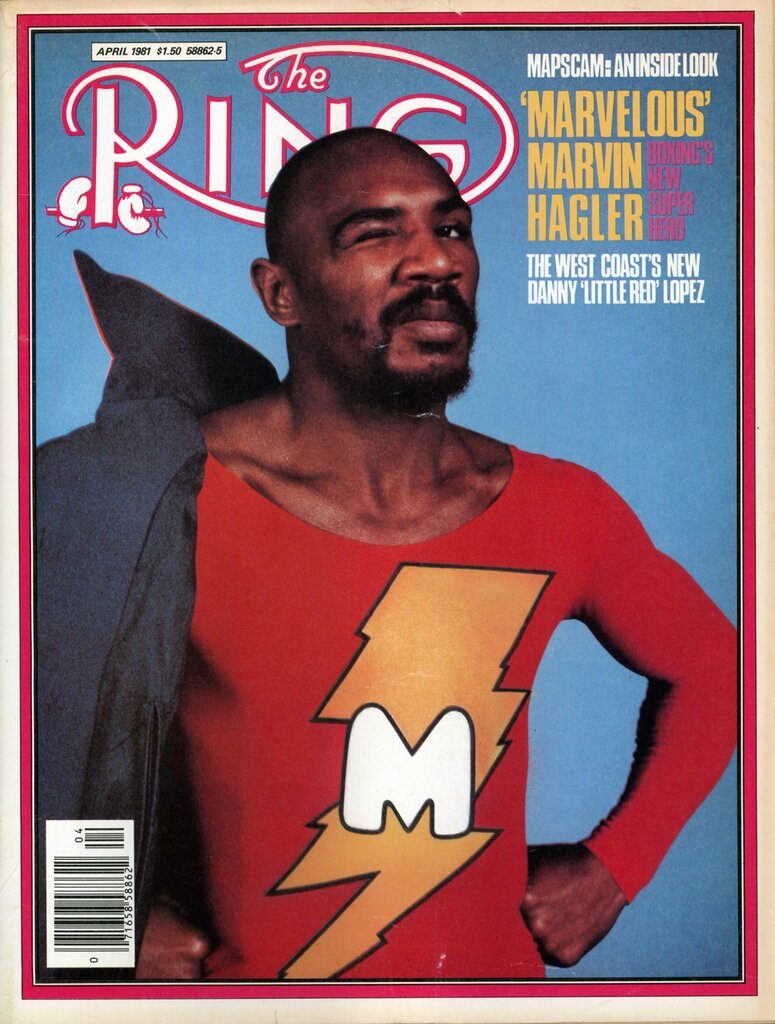

April 1981 issue

Speaking to ABC’s Howard Cosell, Hagler, wearing a makeshift golden crown, declared “It’s sweet, Howie; it brings a tear to my eye. I knew that one day I would be here, and all the roadwork and the boxing all paid off. I felt as though that I learned a lot from the Antuofermo fight; I wanted it real bad and I think that’s what I did. This time, my motto was ‘take it from him’ and that’s exactly what I did. I only had two things on my mind and that was ‘destruction and destroy’ and bring the championship back home.”

Three days later, Hagler returned to Brockton and received a hero’s welcome, a welcome that, according to the Associated Press, included a motorcade-turned-parade and a celebration whose guests included Rocky Marciano’s widow and Hagler’s attorney Steve Wainwright, who kept his promised to shave his own head if Hagler won the championship.

“I’m shaking all over,” he said after he was presented a key to the city. “I’m shaking from my knees to my shoulders just being with you beautiful people. I can’t express my true feelings; I just want to say ‘thanks God, from my heart.’”

One crucial item was missing from this event — Hagler’s newly won title belt. Thanks to the post-fight disturbance, British officials were forced to cancel the customary presentation.

Hagler would go on to become one of history’s greatest middleweights as he logged 11 successful title defenses, earned two Fighter of the Year awards from The Ring in 1983 and 1985 (the latter of which was shared with Donald Curry) and exit the ring with a sterling 62-3-2 (52 KOs) record.

As for Minter, he blamed himself for not following his original game blueprint.

“I never boxed to plan,” he told Carpenter in his dressing room. “All through my training sessions — not just my corner men but other people — were saying to me ‘whatever you do, do not get involved with this guy for the first five or six rounds.’ (After that) then start pressing forward and try to take him out. I blew it, really. It was definitely my fault for having a fight with the guy.”

Minter said the desperation he felt after being cut in the fight’s opening moments forced his hand — or, more precisely, his hands.

“I got cut early, and when you don’t know how bad it is you think, ‘right, I’m cut and I’ve still got 14 rounds to go. I’m going to see if I can take him out.’ That’s what enters your mind. If I never got injured, maybe I would’ve kept it at long range.”

But he did get injured, and the cuts required 17 stitches to close. While Minter’s wounds eventually healed, the stain left behind by one of boxing history’s most shameful incidents remains.

Minter would fight just three more times following the Hagler loss: A 10-round unanimous decision over Ernie Singletary on St. Patrick’s Day 1981, a 10-round split decision defeat to Mustafa Hamsho in June 1981 and a third-round TKO loss to Tony Sibson three months later. Minter retired with a record of 39-9 (23 KOs), the honor that comes with being a champion at all levels during a challenging era and making his mark in life. That life ended on September 10, 2020 following a battle with cancer. He was 69 years old.

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, West Virginia. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 19 writing awards, including two first-place awards, since 2011. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics” (available on Amazon) and the co-author of “Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers” (also available on Amazon). To contact Groves, use the email [email protected] or send him a message via Facebook.

READ THE MARCH ISSUE OF THE RING FOR FREE VIA THE NEW APP NOW. SUBSCRIBE NOW TO ACCESS MORE THAN 10 YEARS OF BACK ISSUES.