Meet manager Peter Kahn, whose fighting blood was forged from the Holocaust

This is one in a series of backstories on boxing managers who are making an impact on the sport today.

The boys would wonder what grandma Nona was talking about. They would look at each other and often laugh, because to them, it made no sense. The numbers on grandma’s arm didn’t add up.

Peter Kahn was around eight, and his younger brother six at the time. They knew enough to realize that the tattooed numbers on the inside of their grandmother’s left forearm weren’t a phone number.

They didn’t know that those numbers never went away. Those numbers—77761—branded in deep blue, were meant to tell a stark truth no child could comprehend.

Still, the digits caused curiosity.

Bella Cohen would answer her grandsons, “They’re just a reminder of my phone number in case I forget.”

Peter Kahn is a boxing manager. He feels that it’s his calling, because he derives from a family of fighters, starting with his spunky, 5-foot-1, 94-year-old maternal grandmother, who for two years survived the Nazi concentration camps at Auschwitz-Birkenau and Bergen-Belsen.

You can find Bella Cohen’s testimony in the Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C.

You can find her eternal fighting spirit coursing through her grandson Peter.

Aside from the small canard about the tattoo, Bella had no filter with him.

She would tell him graphic stories of what she witnessed. Only she and her sister survived of 13 children. Inside the concentration camps, Bella would steal food for the both of them. The times Bella was caught prison guards beat her hands, feet and skull with clubs.

Bella still has a lump on the top of her head from getting hit by a Nazi SS rifle butt during a death march because she helped someone walk. She would sneak out at night under the barracks planks to sift through the bloated dead bodies looking for relatives for closure.

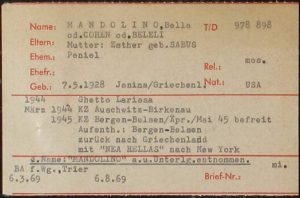

Her head shaved and paper-thin skin showing protruding elbow and knee joints, Bella was finally rescued by the British 11th Armored Division that intercepted a death march from Bergen-Belsen, where Anne Frank died. There is a very good chance, based on certified documentation, Bella Beleli, her maiden name, and Anne Frank were together.

Bella Beleli’s concentration camp paperwork.

Life was a minute-to-minute struggle for Bella between the ages of 15 to 17, skirting random executions for not walking fast enough. Miserable sanitary conditions caused outbreaks of dysentery, typhus, tuberculosis and typhoid fever. When the British arrived on April 15, 1945, they found 60,000 half-starved scarecrows—and 35,000 corpses.

Somehow, Bella survived.

“It’s why I say fighting is in my blood; my DNA is filled with people who have overcome adversity and literally fought for survival,” says Kahn, a 2019 Boxing Writers Association of America Manager of the Year candidate. “I grew up with my grandmother’s stories. It’s apropos, I guess, considering the business in which I work.

“Her story is a part of me. When I was old enough to understand, I was angry, really angry for what they went through. I had no idea that this is what molded their personalities, and how that translated into how they raised my mother. My grandparents were overly protective of my mother.

“My grandmother and all Holocaust survivors never went through therapy. They went through hell and thought a different way growing up. Holocaust survivors are inclined to be very protective. They picked up their lives and moved on like millions of other Holocaust survivors. To this day, I can’t imagine what my grandmother went through—and how she survived.”

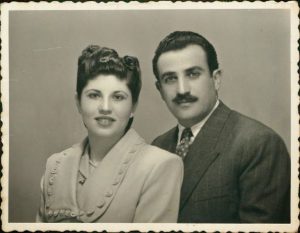

Bella and Peniel Cohen, Peter Kahn’s maternal grandparents. Peniel himself survived Auschwitz.

If there was no Bella, there wouldn’t have been Esther, Kahn’s mother. And if there was no Esther, Kahn wouldn’t be here in this wacky world of boxing.

Kahn, 48, graduated Syracuse in 1994 with a psychology degree. In school, he played for the soccer team as a goalie and competed as an amateur boxer with 40 fights. Upon graduation, he thought about working in the music industry.

His first job out of college was in Manhattan, working for an agency that booked R&B and hip-hop acts. He was a glorified gopher, doing everything from fetching coffee, to running dry cleaning errands, to answering phones at the reception desk. His ambition told him something better was out there.

So, when his parents moved to South Florida, Kahn went with them to contemplate his next move. The switch happened to coincide with someone else’s move to South Florida, Don King.

Kahn, looking like he walked out of a senior prom portrait, had aspirations of having a pro fight. Through a local PAL gym, he became acquainted with some of the regional promoters, fighters and managers.

In early 1995, he had the temerity to make a life-changing cold call to Top Rank’s chief operating officer Brad Jacobs, who in the mid-1990s was the head of USA Network’s Tuesday Night Fights at the time. Jacobs gave Kahn, who he never met before, 90 minutes over the phone.

Jacobs connected Kahn to promoter Mike Acri, who put Kahn in camp with Hector “Macho” Camacho.

That escalated to working on a Don King Showtime fight on May 27, 1995, which featured WBA super middleweight titlist Frankie Liles against Frederic Seillier in the main event.

Kahn wound up doing everything. Airport runs, fighter pick-ups, hotel check-ins, licensing the fighter camps, running fighters for medicals, taking the scale from one end of Fort Lauderdale to the other.

You name it, Kahn did it.

Basically, he was fetching coffee again.

There were 14 fights that night. He ran gloves, he swept the ring, folded the chairs, and brought the fighters back to the hotel. The card began at 2 p.m. Kahn didn’t leave the Fort Lauderdale Convention Center until 2 a.m. the next morning.

He was promised money from a local promoter, who King enlisted to put together the undercard. However, there was a problem. Kahn was never paid. He tried tracking down the local guy. He never got an answer. Frustrated, Kahn began calling Don King Productions. Dana Jamison, who was then King’s vice president of boxing operations, called Kahn in after remembering his work ethic on the Liles- Seillier show.

Kahn’s reward?

He did a $1,000 worth of work for two weeks.

What did he receive? A whole $200.

A 23-year-old Peter Kahn with Hall of Famer Don King. One Kahn’s earliest experiences in boxing came under King.

A few weeks went by when Kahn received a message on his answering machine from Jamison, telling him that he had been hired for a job he never applied for in King’s boxing operations.

Seconds after hearing the news, it seemed, he was on a plane to Las Vegas to work on the Mike Tyson-Peter McNeeley card, Tyson’s first fight back since serving a three-year prison stint of the Desiree Washington rape conviction.

“I did what I was told to do, which meant doing everything,” recalled Kahn, laughing. “I remember reporting to Don King’s office, and in the cubical across from me was Abel Sanchez, and guys like Michael Marley and Marty Corwin were there.

“A lot of relationships in boxing that still exist to this day really started back then. Guys that have grown to do great things. Everyone who wanted to get to Don King had to get to Dana Jamison. And if you wanted to get to Dana Jamison, you had to get to me.”

There was a difference this time to fetching.

This time, he saw a future.

Though he’s closing in on 50, Kahn looks like he’s in his early-30s. He’s about to enter his fourth decade in boxing. “The one thing you can’t shortcut in boxing is experience,” Kahn likes to tell his fighters. “The same goes with managing.”

In March 2018, when Kahn was sitting at the BWAA awards dinner, he made another major choice. He looked around at some of the captains of the boxing world and decided he would commit to managing fulltime. He would get out of the promotion business and begin building his own company.

He had once co-managed IBF junior lightweight titlist Robert “Grandpa” Garcia in 1996. He worked with two-division titlist Randall Bailey, and numerous other belt holders.

“The thing that I realized when I was working for Don King was that the managers made all of the money,” said Kahn, who is managing a diverse group of 16 fighters, among them promising prospects Xander Zayas, Aaron Aponte and Trinidad Vargas. “I realized when these guys were getting signed to five-year contracts, the managers were taking 33.3 percent of their purse monies and basically showing up three times a year to a fight.

Hall of Fame promoter Bob Arum signing Xander Zayas, one of Peter Kahn’s potential future stars.

“I thought that was unconscionable. You have these guys going in taking all of the risk, with the trainer making 10 percent and the manager was making that much, just off a phone call to get them signed? That seemed to me the balance of power was with everyone except the fighter. The fighter was giving up 43.3 percent before they even stepped into the ring. I thought there was something wrong with that.”

Kahn’s model is far different. He takes 10 percent across the board from his fighters. He hides nothing. He values character and trust. He’s part of the new breed, those who aren’t making deals in smoky backrooms.

Boxing can be a creepy business, filled with creeps. Kahn is not one of them.

“I admire the diversity and familial environment that exists in boxing,” said Kahn, whose paternal grandfather, Chaim Kahane, came to the U.S. from Poland as a 9-year-old orphan. When Chaim landed at Ellis Island with his 14-year-old sister, the name was changed to Kahn.

Chaim was the one who initially introduced Peter to boxing, telling him stories about growing up in Jake LaMotta’s Pelham Parkway neighborhood in the Bronx.

“Those stories piqued my interest in the sport,” says Peter, whose maternal grandfather, Peniel, survived the death camp at Auschwitz-Birkenau. “Boxing is like no other sport. Boxing people know what I mean. With all of the inequality that takes place in the world, the boxing ring can be a great equalizer.”

It’s what encouraged Zayas, a potential superstar, to sign with Kahn.

“I call Peter ‘Manager of the Year,’ because he’s always looking out for me,” said Zayas, who took some time out from home work to finish up his high school diploma. “What I liked about Peter was that he took in me and my family. It’s like I’m part of his family. They’re always with me.

“We have a great relationship and good communication. Peter has known me since I was 13. He breaks everything down. That was the most important thing for us. We all trust him. That’s why I signed with him.”

Kahn, whose wife is Colombian, is the father of three boys ranging in age from 18 to 11. His oldest was there at Stoneman Douglas High School in February 2018 when a crazed gunman killed 17. Kahn couldn’t reach him for 70 minutes that day.

A few years ago, the boys became aware of their great grandmother’s plight when the family visited the Holocaust Memorial Museum.

Peter Kahn and his remarkable grandmother Bella, who survived two Nazi concentration camps and just turned 94 in May.

When the British army arrived in Germany, Bella wasn’t much older than her great grandchildren, scavenging for food holed up in a wooded area around a church. British soldiers approached Bella and asked her if she wanted them to kill a captured Nazi SS soldier.

Frail and shivering, Bella told them “No, I’m not like them.”

“I’m involved in boxing, but I don’t think I’ll ever come across anyone who is as brave as my grandmother,” Kahn said. “I think what will always resonate with me and Holocaust survivors is their ability to move forward and not lose their Jewish faith.

“My grandmother is the toughest person I’ll ever meet in my life. It’s why my message is about the fight for life.”

Joseph Santoliquito is an award-winning sportswriter who has been working for Ring Magazine/RingTV.com since October 1997 and is the president of the Boxing Writers Association of America. He can be followed on twitter @JSantoliquito.

READ THE MARCH ISSUE OF THE RING FOR FREE VIA THE NEW APP NOW. SUBSCRIBE NOW TO ACCESS MORE THAN 10 YEARS OF BACK ISSUES.