Thell Torrence remembers Hedgemon Lewis

Day after day, the numbers chronicling the damage inflicted by the coronavirus pandemic continue to mount. As of this writing, more than one million cases have been confirmed, and, of those, nearly 53,000 have perished. One of its victims was Hedgemon Lewis, a former welterweight champion as recognized by the New York State Athletic Commission as well as a valued assistant to Hall of Fame trainer Eddie Futch. Lewis, who had already been weakened by ill health for several years and was residing in an assisted living facility in Detroit, was claimed March 31 due to complications sparked by COVID-19. He was 74.

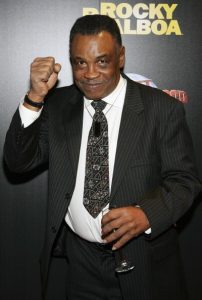

A retired and still healthy Lewis at a party following the Las Vegas premiere of the movie “Rocky Balboa” at the Aladdin Casino & Resort, December 2006, in Las Vegas. Photo by Ethan Miller/Getty Images

One of the men who was there for much of Lewis’ journey through life was 83-year-old Thell Torrence, whose own path was similar to Lewis’ in that he was a onetime fighter (10-3-1, 7 KO according to Boxrec) that extended his life in the sport as an assistant to Futch. Although Torrence had not seen Lewis since the former fighter returned to Detroit in 2002, he said he remained in touch by phone until last year.

“He sounded good, and we communicated quite often, but it eventually got to the point that he had trouble,” he said. He added that he had intended to travel and see Lewis but opted not to go, a decision for which he expressed regret. As for Lewis, he said, he had no reason to feel sorry for anything he did.

“He was a smart kid, academically and in every other way,” he said. “But he loved boxing and that was where his interest was. He earned a real estate license early in his pro career – he took the test and he passed it – and he had a lot of abilities and had a lot of plans, but, like everybody else, when your career is over, it’s hard to execute those plans successfully.”

Inside the ring, however, he excelled. Born in Greensboro, Alabama on February 25, 1946, Lewis began his boxing career at age 12 in Detroit. As an amateur he assembled a 72-6 record, capturing a National Golden Gloves title as a lightweight and winning AAU and National Golden Glove championships at welterweight.

“Back then, if you just went to the Nationals you were a good fighter,” Torrence said. “But if you make the national team and win? That was huge.”

He turned pro with a second-round corner retirement against fellow debutante Arnold Bushman on May 13, 1966 in Cincinnati. Following a six-round decision over Dawson Smith in Detroit’s Cobo Arena that raised his record to 8-0 (5), chief second Luther Burgess brought Lewis (as well as stablemate Lester Felton) to the Hoover Street Gym in Los Angeles in order to be guided by Futch, Burgess’ onetime trainer.

Futch not only was impressed by Lewis’ skills, he was won over by his willingness to listen, learn and execute.

Young Lewis was a Ring-rated welterweight contender for many years.

“Hedge was a brilliant fighter,” Torrence said. “Very smart, very slick, good reflexes and an excellent left hook to the body. He didn’t do a lot of dancing, but he was quick on his feet and a very smart thinker. He understood how to punch, when to punch and where to punch, and his ring generalship was very good. He didn’t waste a lot of punches and every one of them had a purpose. He had a good teacher in Burgess – who was also Eddie’s fighter – so he brought those basic fundamentals with him. But he was also respectful and teachable. You have guys who have a lot of ability, but they aren’t teachable and thus they could not make adjustments. Eddie had no time for fighters like that. But Hedge was teachable; he listened well, and he thought well under pressure. Other kids in the gym would look at him and try to copy the things he did.”

Futch also may have been impressed by what motivated him to succeed.

“He always wanted to make sure he helped his sisters,” Torrence recalled. “He was very close to his sisters and his mom, and he wanted to help put his sisters through college. During his fighting days, that was his number-one goal and to that end he gave them part of his purses.” When asked if Lewis was successful, Torrence said “yes.”

His potential was such that Hollywood heavyweights Ryan O’Neal, Bill Cosby and Robert Goulet agreed to be part of a syndicate designed to provide Lewis financial support. Lewis rewarded their faith by his performances inside the squared circle.

Lewis won his first 22 fights before recording his first loss in July 1968, a ninth-round TKO to number-two rated Ernie “Indian Red” Lopez by ninth round TKO at the Olympic Auditorium in Los Angeles. He won his next six straight – including a decision over future 154-pound champion Oscar Albarado and a revenge points victory over Lopez — before losing the rubbermatch to the older brother of Hall of Famer Danny “Little Red” Lopez by 10th-round TKO.

Over the next two years, Lewis went 12-1 with one no decision and became the number-one contender for world welterweight champion Jose Napoles. The match was staged on December 14, 1971 at The Forum in Los Angeles, the first of two world title bouts on the bill.

Over the next two years, Lewis went 12-1 with one no decision and became the number-one contender for world welterweight champion Jose Napoles. The match was staged on December 14, 1971 at The Forum in Los Angeles, the first of two world title bouts on the bill.

The 31-year-old Napoles was making the first defense of his second reign following three non-title wins against David Melendez (KO 5), Jean Josselin (KO 5) and Esteban Alfredo Osuna (W 10), and once the opening bell sounded it was evident that the 25-year-old challenger had the hand speed, mobility and sharpness to back up his mandatory challenger status.

“Eddie had scouted Napoles leading up to the fight,” Torrance recalled. “I was very high on Hedge because of the way he was handling the welterweights and the middleweights in the gym.”

Lewis enjoyed several good moments in the first half of the contest as he followed Futch’s game plan of staying at long range, using feints to draw leads and countering off those leads. Lewis briefly buzzed the champion in rounds three and five, and he allowed himself a moment or two of showboating after connecting with a series of flush jabs in round seven.

But Napoles began to pull away starting in the eighth thanks to his consistent aggression and heavier punching. In the final seconds of Round 14, however, a stiff counter right to the chin caused the champion’s legs to dip. Concerned that Lewis could steal a close decision, Napoles turned on the jets in Round 15 and closed the show with a champion’s flourish. The decision was close – 8-7, 8-6 and 9-4 under the California scoring system – but Napoles still exited the ring as the world champion.

“I never was hurt but I was mad,” Napoles reportedly said. “He ran around too much to make it a good fight. He jabbed me pretty good in a few rounds and that’s how I got the cut. But he never hit me with a punch that hurt.”

Lewis, of course, disagreed.

“I thought I won it,” he said then. “He might have hit harder, but I got in more punches.”

“It was a good, close fight,” said Torrence. “Maybe we could have gotten the decision, but you’ve got to remember that Napoles was quite the fighter.”

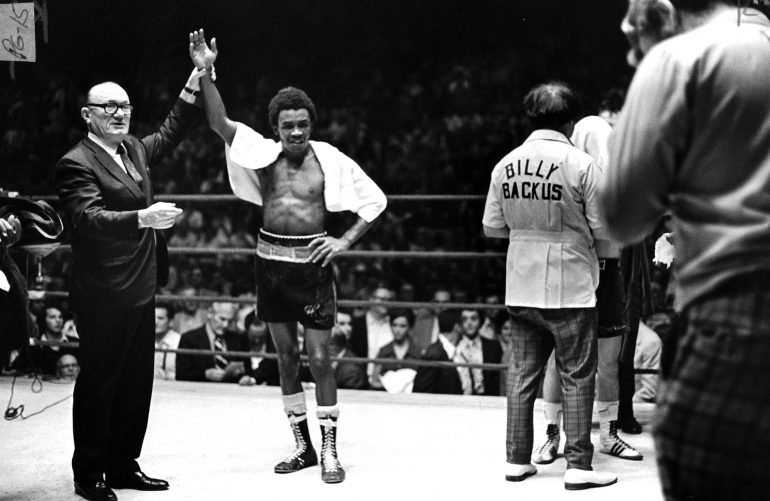

Lewis and Backus at the War Memorial Auditorium in Syracuse, New York, in June 1972. Photo / The Ring Magazine via Getty Images

Just 39 days after scoring a 10-round points victory over Ruben Vazquez Zamora on May 8, 1972, Lewis was paired with former welterweight champion Billy Backus for the NYSAC version of the welterweight championship. The New York-based sanctioning body demanded that Napoles, who had split two previous bouts with Backus, meet the New Yorker for a third time, and when Napoles refused they withdrew their recognition and arranged a fight between Backus and Lewis at Syracuse’s War Memorial Auditorium, located just 25 miles west of Backus’ hometown of Canastota.

But Lewis upset the applecart by scoring a second-round knockdown, then carving out a narrow but unanimous decision victory. Following two non-title wins over Mario Marquez (KO 2) and Jose Luis Baltazar (W 10), Lewis returned to Syracuse to meet Backus. This time, Lewis won much more easily, scoring nearly at will and opening cuts over both eyes en route to a lopsided 15-round decision victory.

According to Boxrec, this was Lewis’ last defense of the NYSAC bauble, but because he was rated first – and because he added six victories between March 1973 and April 1974 – he earned a second shot at Napoles’ crown.

“We were confident and we thought he could do it after seeing the first fight,” Torrence said. “He was at his peak, but we knew that it was going to be tough to beat Napoles in Mexico. We were preparing to fight him in Monterrey but the fight location was changed to Mexico City the week before the fight and that threw everything off. The people were as loud as anything I’ve heard and it seemed like the whole country was against us.”

The 34-year-old Napoles, nearly six months removed from his failed attempt to win the middleweight title from Carlos Monzon, exerted pressure from the start, connected far more frequently than was the case in their first fight, won every round on all scorecards and scored a ninth-round TKO.

“Ryan O’Neal was with us that night and had he won it would have been a great celebration,” Torrence said. “But it was not to be. He was a proud guy, a good guy, determined and wanted to win badly. But that’s boxing for you.”

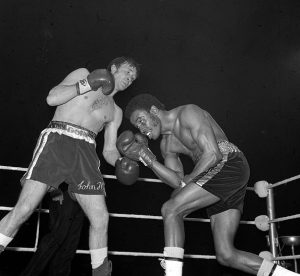

Welterweight champion John H. Stracey and Lewis during Round 4 their title fight at Wembley. Photo by PA Images via Getty Images

Despite going 2-2-1 in his next five fights – including back-to-back draws against future champion Carlos Palomino and the respected Harold Weston in the final bouts of the stretch – Lewis was granted a title shot against WBC king John H. Stracey, who was making the first defense of his title following a shocking, off-the-floor sixth-round TKO over Napoles four months earlier. The 30-year-old Lewis started well, but the fight turned once Stracey shifted his attack to the body. The result was a 10th-round TKO, destined to be the final fight of a nearly 10-year career that saw him compile a record of 53-7-2 (26) with one no-decision.

Thanks to his fusion of aptitude and attitude, Lewis was allowed to make the transition from Futch fighter to Futch assistant.

“Hedge was very close to Eddie; he was a real easy guy to work with and his attitude was good,” Torrence said. “We had a unique program – a program that produced 22 world champions – and assistants were brought in to help maintain the structure that was set up. He wanted to stay in California, and because he had great ability and understood the techniques, he was a benefit to the team and he was absorbed into the camp.”

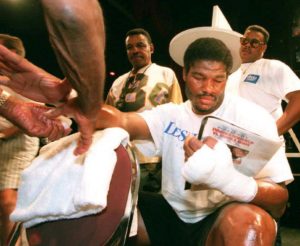

Lewis (center) oversees Riddick Bowe as he is being taped up by Eddie Futch before a public workout session prior to Bowe’s rubbermatch with Evander Holyfield. Photo / John Gurzinski/AFP via Getty Images

Along with Torrence and Futch, Lewis worked with the likes of Ken Norton, Virgil Hill, Mike McCallum, Mike Weaver, Montell Griffin, Marlon

Starling, Riddick Bowe and Wayne McCullough, among many others. Torrence said Lewis remained with Team Futch until he decided to return to Detroit, where he would remain for the rest of his life.

“Hedgemon was a real gentleman,” Torrence said when asked to sum up his friend and colleague. “Very meek, very smart and loved boxing. He started out as a boxer and he became a world champion. He trained and worked with some of the greatest fighters in the world and he was able to accomplish his goals in life. There was nothing he wanted more than to be a great boxer and a trainer, and he doesn’t have anything to regret.”

COVID-19 may have scored a victory over the weakened body of Hedgemon Lewis, but it can do nothing to touch his soul, his accomplishments and the love he earned from those who knew and loved him.

*

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, West Virginia. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 18 writing honors, including first-place awards in 2011 and 2013. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics” (available on Amazon) and the co-author of “Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers” (also available on Amazon). To contact Groves use the email [email protected] or send him a message via Facebook.