COVID-19 isn’t the first pandemic to halt boxing

At a time when boxing is on more channels and platforms than ever before, it felt eery to have a weekend pass without a significant boxing event. The biggest show to make it to American airwaves was the ShoBox card in Minnesota, which saw Brandun Lee pummel an overmatched Camilo Prieto in front of a few dozen friends and event personnel in a ballroom that was already built like a television studio.

Given the calls for “social distancing” and avoiding large crowds amid the spreading COVID-19 pandemic, it’s understandable that sports leagues like the NBA and NHL have suspended their seasons. Boxing has also been impacted, with California calling for all events of 250 or more to be canceled, and New York shutting down events with 500 or more being sidelined.

Among the shows postponed were Shakur Stevenson’s scheduled first defense of the WBO featherweight title, nixed two days before Saturday’s fight night, just hours after Top Rank announced that show, and the St. Patrick’s Day show at the Hulu Theater at Madison Square Garden, would take place without fans in attendance.

Mick Conlan, the unbeaten featherweight who was to headline the show on Tuesday, admitted he was uneasy during last Thursday’s press conference, speaking face-to-face with reporters at a time when the U.S. has been slow to conduct testing (estimates as of March 11 show that only 23 tests per million had been conducted in the U.S., compared to 3,692 per million for South Korea).

“We don’t know who has the virus. You could have no symptoms and still have it,” said Conlan, who had increased his hand washing during his time in New York, and even wiped down the seats on the plane with antiseptic wipes while boarding.

The Nevada State Athletic Commission has taken a wait-and-see approach, canceling the western qualifiers amateur tournament, set for March 21-28 in Reno, with a March 25 meeting scheduled to decide on future events. Japan has canceled all boxing events through the end of April, while the Philippines has suspended events for the foreseeable future. The uncertainty has put the boxing world on hold, with more postponements and cancellations expected.

This pandemic is something most of this generation hasn’t seen, nor the previous, nor the one before that. But the one before that could have told you about the Spanish Influenza outbreak of 1918-1919, which is considered one of the worst public health crises in recorded history. An estimated 500 million – or one-third of the planet’s population – was infected, with 20 to 50 million people dying, sometimes within hours of their first symptoms. The flu spread quickly, expedited by the mass transportation of troops during the first World War, and the unwillingness of governments to acknowledge the outbreak, lest they appear vulnerable to enemies abroad.

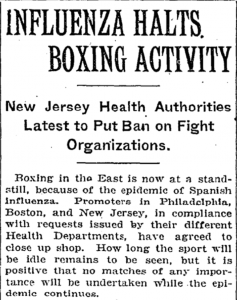

Boxing on the east coast was brought to a “standstill,” according to the October 13, 1918 edition of the New York Times, with promoters in Philadelphia, Boston and New Jersey complying with requests from local health authorities to call off the bouts. “How long the sport will be idle remains to be seen, but it is positive that no matches of any importance will be undertaken while the epidemic continues,” the story read.

Among the bouts affected by the sudden shuttering of boxing clubs was the bout between Jack Dempsey, then a rising a heavyweight contender, and reigning light heavyweight champion Battling Levinsky, which had been scheduled for early October in Philadelphia. The bout finally happened on November 6, with Dempsey knocking out the light heavyweight contender in three rounds, clearing the way for Dempsey to win the heavyweight championship the following year.

News reports at the time also show gathering bans impacting boxing shows in Detroit, Sacramento and Portland, and an article in the October 24 edition of The American Guardian newspaper in Oklahoma City noted that the midwest had been particularly hard hit, with boxing venues in cities like Milwaukee, Toledo and Peoria, Ill. having to delay their openings.

Boxing served as a form of amusement to the troops, and to raise funds for the war effort, and enlistees watched fights while wearing face masks at ringside. “Some have been stopped through the influenza, but on the whole the recruits like to have their boxing whether there is illness or not,” read the article.

While the new coronavirus has shown its worst effect on older patients, the Spanish Flu outbreak was particularly lethal to otherwise healthy adults aged 20-40. That meant a number of boxers, many in the primes of their lives, were among the dead.

The highest profile boxer to lose his life was “Battling” Jim Johnson, the New Jersey-born heavyweight who traveled the U.S. and Europe fighting the other top black heavyweights of his time, including Joe Jeannette, Sam Langford and Harry Wills. Johnson did get a crack at the world heavyweight championship, in 1913, battling Jack Johnson to a draw in Paris in 1913.

A thirteenth meeting with Langford, which was to take place in Lowell, Mass., was postponed due to the moratorium on fights. Johnson contracted the flu while in the state, and died in Boston on Nov. 6, at age 31.

In a few short weeks, a number of popular fighters who filled venues across the country had succumbed. What’s most staggering are their ages.

Among them were Terry Martin (47-25-13, 29 KOs), a Norway native based in Philadelphia who had battled former world welterweight champion Joe Walcott and the legendary Harry Greb, who died on October 14 at age 33; heavyweight Jim Stewart (21-7-1, 19 KOs) of Brooklyn died on September 26 at age 31; Joe Tuber (10-2, 9 KOs), bantamweight from Philadelphia, died at age 21; Matty Baldwin (84-27-55, 28 KOs), a lightweight from Boston, died October 9 at age 33; Baltimore Dundee (10-1-3, 4 KOs), a bantamweight born Samuel Ranzino, died on December 31 at age 17.

A story in the November 13, 1918 issue of the Des Moines Tribute underlines the frequency of boxing deaths during the flu pandemic.

Other boxing figures who died in the pandemic were Lorenzo Snow, founder of the Trinity Boxing Club in lower Manhattan, and Paddy Carroll, a boxing promoter and manager out of Chicago, who died at age 59.

The biggest names impacted were those who survived.

Tommy Burns, the Canadian who held the heavyweight championship from 1906 before losing it to Jack Johnson in 1908, was hospitalized in Vancouver, Canada after contracting influenza while serving as a sergeant in the 1st Depot Battalion at Hastings Park in the Canadian Army. “It is reported that his condition is serious, the malady having attacked him in its most violent form,” read the October 21, 1918 edition of the Edmonton Journal, just a month after his fourth round KO win over Bob Bracken.

Burns, then 37, made a “remarkably quick recovery,” according to the October 25 edition of the Vancouver Daily World. Burns fought just once more, being stopped in 7 rounds by Joe Beckett in 1920, and lived to age 73.

Another former heavyweight champion who contracted the virus was James J. Jeffries, who had knocked out the likewise mythical Bob Fitzsimmons in 1899 to win the championship. Jeffries hadn’t fought since 1910, when he came out of retirement in a failed attempt to wrest the title back from Jack Johnson in their infamous match, and was residing in Los Angeles when he fell ill. Jeffries was described as “dangerously ill,” and physicians anticipated he would die, but he made a quick recovery, according to the Nov. 6 issue of the Boston Post.

In time, the flu subsided, and both boxing and life resumed. The lessons learned led to the development of vaccines, and improvements in treatment which have reduced death tolls in subsequent flu outbreaks. The same will happen for COVID-19, as medical professionals brush aside personal risk to provide heroics, and researchers scramble to develop treatments.

The handshakes that have been replaced by elbow bumps will return, as will the crowds that inspire fighters to rise to feats of bravery in the ring.

But just like a counterpuncher waiting for an opening, patience is the key.

Ryan Songalia is a member of the Boxing Writers Association of America and part of the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism Class of 2020. He can be reached at [email protected].