The Travelin’ Man goes to Allentown: Part Two

Please click here to read Part One.

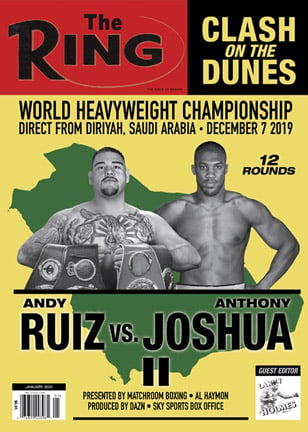

Saturday, February 8 (continued): For three hours 11 minutes in Allentown, Pennsylvania, the live crowd inside the PPL Center and those who chose to watch the proceedings live on Showtime were treated to multiple sides of the boxing game: (1) A thrilling, pulsating title eliminator with multiple plot twists that ended in a controversial split decision, (2) a stunning strategic twist that helped a 39-year-old amateur legend snuff out his 37-year-old opponent’s momentum created by a hellish opening-round assault and (3) a longtime featherweight titlist showing a determined mandatory challenger exactly why he’s held his belt for so long.

The trio of fights lasted the maximum 36 rounds and the audience’s range of emotions covered the gamut: Animalistic, appreciative cheers, throaty boos that expressed anger, frustration and periods of understated anticipation and modest, moderate buzzing that mirrored the action inside the squared circle. In the end, “The War,” “The Master Class” and “The Return of Mr. Russell” comprised quite the roller coaster ride.

The opening fight of the telecast – The War – saw once-beaten Panamanian Jaime Arboleda remain once-beaten (16-1, 13 knkockouts) thanks to a split decision over Jayson Velez (29-6-1, 21 KOs) that some are calling an early candidate for 2020’s Fight of the Year. Like past winners of the honor, Arboleda-Velez was a drama played out in three distinctive acts. The first saw Velez dominate with speed, mobility, energy and ambition; the second produced a substantial and extended rally by Arboleda against a seemingly eroded Velez while the third was the best act of all as Velez summoned a final surge marked by a final-round knockdown. It was marvelous theater but the good feelings were spoiled by a verdict favoring Arboleda that stood in sharp contrast to Velez’s blowtorch finish.

But while the PPL Center crowd vented its anger and Twitter users favored Velez by a 64-36 margin, the numbers revealed why the result ended up being what it was. Most viewers favoring Velez will point to the first three rounds that saw the Puerto Rican get off to a flying start (67-39 overall, 17-12 jabs, 50-27 power) as well as the garrison finish in Rounds 10 (18-8 overall and 16-6 power) and 12, when he produced fight-highs of 41 total connects, 41 landed power punches, 93 total punches thrown and 89 power punch attempts compared to Arboleda’s 14 of 66 overall and 12 of 42 power.

Jaime Arboleda (left) vs. Jayson Velez. Photo credit: Amanda Westcott/SHOWTIME

However Velez’s sterling start and operatic finish overshadowed what Arboleda achieved in Rounds 4 through 9 as well as in Round 11. Arboleda, who appeared beyond his depth in the first three rounds, settled down then cranked up. He followed a respectable 18 of 67 Round 3 with a 30 of 81 fourth that superseded Velez’s 21 of 90 effort. Arboleda then proceeded to sweep the next five rounds by upping his work rate from 58 in the first three rounds to 84.5, then rebounding from a relatively sluggish 10th (8 of 44 to Velez’s 18 of 64) with a strong 11th (25 of 77 to Velez’s 17 of 74).

Velez entered the 12th with narrow leads of 228-225 and 184-169 power to offset Arboleda’s 56-44 lead in landed jabs and Arboleda boasted accuracy edges of 28%-27% overall and 37%-31% power. However Velez’s torrential 12th extended the veteran’s final leads to 269-239 overall and 225-181 power and while he retained his jab accuracy edge (18%-15%), he snatched a 29%-28% lead in overall accuracy while Arboleda’s power precision edge narrowed to 37%-33%. Interestingly the CompuBox round-by-round breakdown of total connects – which has lined up more often than not with the official scoring because it tracks the key judging component of clean punching – had Arboleda ahead 7-5 and with Velez’s knockdown added to the equation, the breakdown would have had Arboleda ahead 114-113 – the same score submitted by judges Bernard Bruni and Eric Marlinski. So to my eyes, the rendered decision – despite the unfavorable optics at the end – was justified.

“Jayson Velez is a great fighter and has a great style,” Arboleda said in Joe Santoliquito’s fight report. “He was trying to use that (style) to break me down tonight. Velez has faced a lot of good fighters and I believe I belong with those fighters. I had him hurt badly a few times but I just got a little bit ahead of myself and didn’t finish.

“It was a clean shot on the knockdown but it happened because I wasn’t doing what I was supposed to stylistically and with my footwork,” he continued. “I was a bit tired but I wasn’t too hurt. I went right back to fighting.” Because of Arboleda’s work in the middle rounds and in the crucial 11th, he did just enough to emerge victorious in his first fight beyond nine rounds.

Velez, who displayed good sportsmanship immediately after the decision was announced, was disappointed but hopeful.

“It was a close fight but I think I won the fight,” he said. “It could have gone either way. I think I knocked him down twice but they didn’t count one of them. It’s OK. I showed that I’m a warrior like always. I have six losses now but I’ve never been knocked out. I’m still here and I believe I’ll be world champion someday.”

*

For most of his 10-year professional career, Guillermo Rigondeaux – like his countryman Yuriorkis Gamboa – has faced a stylistic quandary. His dominant decision victory over then-pound-for-pound superstar Nonito Donaire in April 2013 on HBO should have vaulted him to a higher level in terms of popularity and money-making potential but, like most defensive geniuses, the two-time Olympic gold medalist was criticized by observers and shunned by potential opponents who saw him as the classic high-risk/low-reward opponent. Then came the debacle against fellow two-time gold medalist Vasiliy Lomachenko, the one man capable of out-thinking the ultimate thinker. Lomachenko’s next-level technique plunged Rigondeaux into levels of frustration he had never experienced during his 493-fight boxing life, so much so he chose to retire on his stool between Rounds 6 and 7 instead of heeding the fighter’s code of competing until the bitter end. The sour conclusion that spawned the nickname “No Mas-Chenko” justified the arguments of his critics, who then added the term “frontrunner” to their list of insults.

While Rigondeaux presents himself as proud, tough and defiant in interviews, he has, from time to time, tried to spice up his game in order to draw more favorable reviews. More than once he produced the rarest of rarities – one-shot body-shot knockouts and his wars with Hisashi Amagasa and Julio Ceja were pulsating, action-packed spectacles in which Rigondeaux was forced to access his bag of intangibles. In fact, the Ceja fight saw Rigondeaux come through the kind of acid test demanded of great champions and it was a test the Cuban forced on himself by inviting a trench war that favored his opponent. Round after round, they exchanged heavy leather and, as one might think, Ceja was getting the better of things. In fact, he struck Rigondeaux with 225 total punches, shattering the previous high of 82 connects by a Rigondeaux opponent. (By the way, that opponent was Nonito Donaire.) Despite the pain, anguish and anxiety, the chancellor of the Cuban Boxing School came through in the clutch and scored the eighth round TKO.

The uncharacteristically exciting bout earned the praise Rigondeaux had long sought. In the post-fight report posted on Bad Left Hook, it was written, “Bottom line, it was a very entertaining, all-action fight and if you’re someone who has started to skip Rigo bouts out of habit, this is one you should seek out.”

Fueled by the praise – and fueled by the confidence that a career-long junior featherweight like himself could overpower a longtime 115-pounder in Liborio Solis – Rigondeaux came out swinging in the opening round. But with 61 seconds remaining, Solis struck with a left hook to the cheek that stiffened Rigondeaux’s body and plunged him toward an abyss he had seldom experienced. Solis correctly gunned for the KO and nearly got it thanks to Ceja-like totals of 28 of 95 overall and 28 of 88 power. Rigondeaux was lucky to have escaped the round with the lights still working and, between rounds, he and chief second Ronnie Shields decided to change course. No longer would Rigondeaux play the foolhardy action hero; he would revert back to the ring master that befuddled hundreds of previous opponents but also ignited howls of derision from those who paid to watch him fight.

When Rigondeaux shifts into Shadow Mode, he is nearly impossible to hit cleanly. His fusion of ring positioning, distance control, subtle movement, knowledge, anticipation and muscle memory form his protective shell on defense while his exquisite timing and reflexes on offense produce the jolting, single-shot, out-of-nowhere bombs that deter opponents from recklessly charging ahead. For Solis, the effects of Rigondeaux’s shell game is similar to that of the Jedi Mind Trick portrayed in “Star Wars”; from Round 2 forward, it was almost as if the Venezuelan had forgotten what he had done in Round 1 and, because he failed to follow up his advantage, his cause was severely compromised.

In Round 2, Solis’ totals cratered as he threw 24 punches compared to 95 in Round 1 and 16 power shots compared to the 88 he unleashed in the opening three minutes. Yes, Solis still managed to out-land Rigondeaux 5-3 overall and 5-2 power but while the Cuban might have lost the round on some scorecards, he was wildly (or, given the temperament, mildly) successful in transforming the contest from a firefight into the cold, clinical chess match that favors Rigondeaux’s off-the-charts brain power.

Round after round, Rigondeaux methodically dissected Solis’ defense and by the end of Round 10, he had taken over the lead in terms of total connects (61-56) after amassing a 13-2 advantage. The Cuban’s cause was considerably helped by his performance in the opening minute of Round 7 – when he scored a “but-for-the-ropes” knockdown with a succession of electrifying lefts – as well as what he achieved in Round 8: Avoiding every one of Solis’ 31 attempted punches.

Guillermo Rigondeaux made a successful move down to bantamweight versus Liborio Solis. Photo by Amanda Westcott/Showtime

By the end of the fight, Rigondeaux, having swept the final six rounds in terms of total connects to take an 8-4 lead, assembled leads of 73-59 overall and 22-4 jabs to offset Solis’ 55-51 edge in power punches. The key to Rigondeaux’s statistical success on offense was his 43%-17% gap in power accuracy but the most indicative number was the following: While Solis landed 28 punches in Round 1, he connected just 31 times in the following 11 rounds to Rigondeaux’s 63.

While Don Ackerman favored Solis’ ineffective aggression (115-112), Ron McNair (116-111) and Kevin Morgan (115-112) recognized the value of Rigondeaux’s strategic command and technical dominance.

“I thought I won the fight,” Solis said. “Going backwards is no way to win a vacant title (a secondary WBA strap unrecognized by The Ring). I put the majority of the pressure on him. I’m not going to argue with the judges but I thought I did enough to win. The punch surprised me on the knockdown but I wasn’t hurt. I was ready to fight immediately after. I hurt him in the first round and that’s what caused him to run. I’d like a rematch because I thought I got the better of him tonight.”

To me, a rematch is very unlikely because of the control Rigondeaux showed while in Shadow Mode. Also Rigondeaux has other goals on his mind, one of which is to move down to Solis’ former stomping grounds at 115, whose roster of beltholders includes Khalid Yafai (WBA), Jerwin Ancajas (IBF), Kazuto Ioka (WBO) and especially Juan Francisco Estrada (WBC).

“Like I’ve showed everyone before, I can fight right in the middle of the ring,” Rigondeaux said through an interpreter. “I tried that in the first round but after that round, Ronnie Shields told me to show him some boxing and cut the ring off. Ronnie Shields is the real champion. The preparation that he gave me for this fight was incredible. Ronnie is one of the best.”

He certainly is and Rigondeaux definitely showed Solis some boxing. Some, including me, will argue that he didn’t cut off the ring on Solis because he mainly fought off the back foot but his superlative skills did create the escape paths he needed to retain his preferred distance while also negating the Venezuelan’s best chance of victory. The only reason the fight was close was because Rigondeaux’s offensive output in some rounds was not overwhelming in comparison to Solis’ (3 of 66 to Solis’ 2 of 27 in Round 3, 1 of 20 to Solis 3 of 46 in Round 6, 3 of 38 to Solis’ 0 of 31 in Round 8 and 6 of 36 to 4 of 43 in Round 9).

The message of the Solis fight should now be clear to Rigondeaux: If you choose to slug with opponents, you’ll please crowds but you’ll do so at your own peril. However if you choose to box in the way that served you so well for so long, the audience will boo but the “W” you seek will be within much easier reach. The final decision, as always, will be yours but you were wise to heed Shields’ advice after Round 1 and you’ll be wise to continue heeding it from now on. If a fight with Estrada comes to pass – or perhaps a “unification” fight with WBA champion Naoya Inoue, who is also the IBF titlist and The Ring Magazine champion – the intelligence and the technical talent will be in the red zone and I, for one, would look forward to seeing it – and potentially counting it.

*

At the start of Round 9, Showtime analyst Al Bernstein said Rigondeaux pitched a shutout in the eighth thanks to limiting Solis to 0 of 31 in terms of total punches. So in that spirit, allow me to make a baseball-oriented comparison: If Rigondeaux is boxing’s Greg Maddux due to his otherworldly intelligence and ability to change speeds and strategies at will, then WBC featherweight titleholder Gary Russell Jr. is like a left-handed Pedro Martinez, a smart athlete who also happens to beat opponents with overt hand speed and, at his best, electric power.

In retaining his belt against mandatory challenger Tugstsogt Nyambayar, Russell controlled the game with his output (72.3 punches per round to Nyambayar’s 58.9), his ability to hit his spots with his hardest pitches (26%-21%) and by keeping the Mongolian challenger at the proper distance from home plate thanks to his set-up pitch, a prolific (39 attempts per round) but inaccurate (6%) jab. This time, however, he didn’t show off his knockdown pitches – the ones that dethroned Jhonny Gonzalez and took out Patrick Hyland, Oscar Escandon and Kiko Martinez – but Russell showed Martinez-level command of his tools by keeping Nyambayar, the dangerous right-handed slugger, at the safe distance needed to out-box, out-fox and out-point him.

“The difference was ring generalship, hand speed and boxing IQ,” Russell said following a performance that produced scores of 118-110 (David Bilocerkowec), 117-111 (John McKaie) and 116-112 (Glenn Feldman). “He had only 11 pro fights – of course he was an Olympic silver medalist – but he only had those 11 pro fights. I’ve had over 30 fights (32 to be exact) and I think my experience was enough to overcome and win this fight.”

The numbers favoring Russell were smaller than the scorecards – 134-122 overall, 30-21 jabs, 104-101 power – mostly because Nyambayar was slightly more accurate overall (17.3%-15.5%) and in jabs (9.3%-6.4%), landed more body shots (50-30) and managed to perform better in the later stages as he adjusted to Russell’s tools (he trailed just 86-84 overall in Rounds 7 through 12 compared to 48-38 in Rounds 1 through 6). The result that he scored more runs on offense (he led 8-4 in the CompuBox round-by-round – or, rather, inning-by-inning – breakdown of total connects) and his control was such that even the vanquished recognized it.

Gary Russell Jr. (right) vs. Tugstsogt Nyambayar. Photo by Amanda Westcott/SHOWTIME

“It wasn’t my night. He was the better man tonight,” Nyambayar said. “I didn’t do my work the way I was supposed to. He is a great champion who fought a great fight. I made a mistake by waiting for him during the fight.”

Sounds like the typical opponent of the prime Pedro Martinez; doesn’t it?

As for Russell, he wants to hunt bigger game such as WBA junior lightweight titlist Leo Santa Cruz (which would make for a fascinating style clash between two men known for their above-average volume) or if he can’t get “El Teremoto” into the ring, he wants to compete at lightweight. But while Russell has the guile to compete at higher weights, does he have enough of a punch to make his larger opponents respect him? After all, the 5-foot-4 ½-inch Russell is short even for a featherweight and against Santa Cruz, he will face deficits of three inches in height and five inches in reach. It will greatly help Russell’s cause that Santa Cruz will assume the role of aggressor but what if he decides to box at long range like he did in his rematches against Abner Mares and Carl Frampton, both of which he won on points while also maintaining his trademark volume? What then? Hopefully we will get to see the answer.

What if the Santa Cruz fight doesn’t happen and he ends up facing lightweight champion Vasiliy Lomachenko and beltholders Teofimo Lopez or Devin Haney? Lomachenko remains the only man to have beaten Russell as a pro and while he has the intelligence to compete with anyone, he also has proven his power at 135 by scoring a one-punch body-shot KO against Jorge Linares and a crushing fourth round TKO of former titlist Anthony Crolla. Lopez is one of the division’s hardest punchers and he has the speed, youth, ferocity and confidence to crush most fighters in his path. Haney, who is currently recuperating from shoulder surgery, may first meet the winner of the “interim” title fight between mandatory challenger Javier Fortuna and Luke Campbell. But even if Haney heals and takes care of business, and even if Russell gets in position to challenge Haney, the Washington, D.C. native will face height and reach deficits (three-and-a-half inches and seven inches respectively) as well as a nearly 10-year age gap. For Russell to end up in Canastota one day, he must find a way to confront and conquer these challenges.

*

After packing my belongings, I – with considerable help with building staffers – found my way back to my hotel room, entered the night’s stats into the master database, sent the files to the various Draft Kings employees and did my best to wind down after the show. It was a struggle and, as a result, it wasn’t until nearly 3:30 a.m. when I turned out the light.

Sunday, February 9: If I’ve learned one thing in my 55-plus years on Earth, it is this: Having a positive attitude will work wonders when confronted with negative situations. Even before I arose at 7:30 a.m., I already knew this would be a long travel day as I would have to check out of the hotel before 11 a.m., drive from Allentown to Philadelphia International Airport, wait for my scheduled 4 p.m. flight to Pittsburgh to arrive, then, after landing, drive two-and-a-half hours home. The best-case scenario would have me at the house by 8:30 p.m. but, as has been the case lately, the best-case scenario didn’t come to pass.

At 9:51 a.m., I received a text from American Airlines that my 4 p.m. departure was changed to 5:45, a development that prompted me to leave the hotel earlier than planned. I hoped that I could arrive in Philadelphia early enough to possibly grab an earlier flight, a gambit that has proven successful in the past.

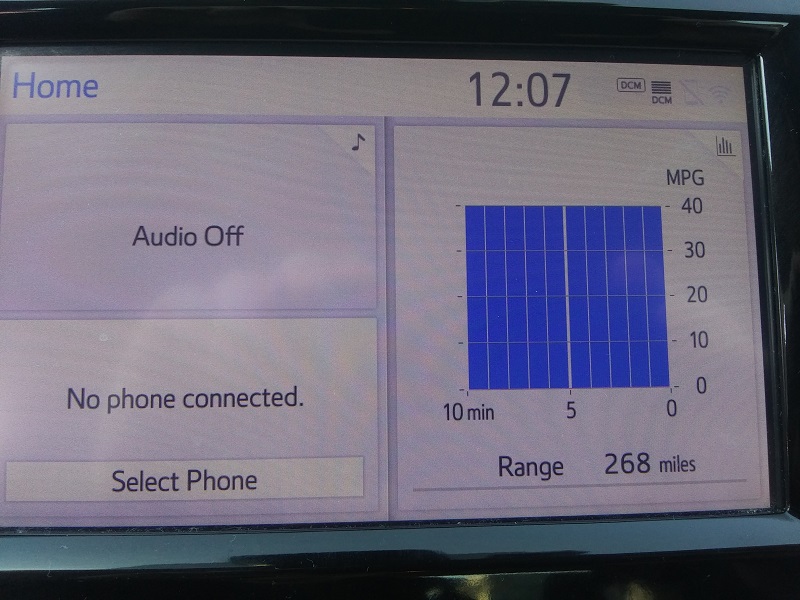

Conditions were great for early February – sunny and a temperature in the mid-30s that eventually climbed into the upper 40s as I worked my way south. As I drove the Toyota Camry on Interstate 476, I noticed that its dashboard included a screen that offered a minute-by-minute breakdown of fuel efficiency – and that I had assembled a streak of several minutes in which I reached the maximum 40 miles-per-gallon reading.

Throughout my life I’ve possessed a strong competitive drive and though my physical abilities have long passed their peak, I still compete against myself on a daily basis. On most days I try to meet – and exceed – the goals I set in terms of completing my various tasks but here I wanted to see if I could string together 10 consecutive minutes of maximum miles-per-gallon readings. My own Subaru has a dashboard feature that gives me a moment-by-moment reading of my driving efficiency, so, over time, I’ve adapted a style that kept me in the green – and in the “green” – most of the time. For that reason, I liked my chances.

I assembled streaks of five, seven and nine minutes but those strings were broken by extended uphill climbs as well as a stop at the Pennsylvania Turnpike toll booth. However as I approached Philadelphia, I knew I had one last chance to “run the table.” That moment came just before I took the exit leading to the airport and by the time I reached the AVIS facility at 12:07 p.m., the string was extended to 14 consecutive minutes.

Lee Groves has always liked a challenge, and during the drive

from Allentown to Philadelphia, that challenge was an environmentally friendly one: Achieve 10 straight minutes of 40 miles-per-gallon driving. This photo, snapped moments after arriving at the AVIS parking lot, is proof that he achieved his goal but, in reality, the string ended at 14 consecutive minutes.

So despite the long wait, I knew I would have to endure before my flight, I entered the airport terminal in an excellent state of mind. Winning does that for you.

After boarding the AVIS bus that would take me to Terminal F, I received another message from American that my flight was still going to depart at 5:45, meaning I would be spending most of the day inside the airport. It would have been easy for me to wallow in self-pity or to lash out in frustration – I’ve seen others in similar spots do just that – but I’ve learned that neither of those responses would make the desired airplane suddenly become the Concorde, slice through the clutter of crap that is the airspace along the Eastern Seaboard and pull into my gate at my preferred time. We as passengers are powerless in many ways, so the best we can do is to make the best of our situation. And I did just that.

I walked to the Terminal F food court, stopped at the Tony Luke’s outlet and ordered a “traditional hoagie cheesesteak” (except they couldn’t include tomatoes because they had run out), plain fries and a diet soda. The sandwich was far larger than I envisioned it to be and the fries were placed inside a small bag. Still, since I hadn’t eaten anything substantive since last night’s crew meal, the big portions hit the spot.

At 2:12 p.m., American Airlines texted me again and the news was bad – my 5:45 p.m. departure was pushed back to 6:28. At first I was perplexed because the weather was sunny in Philadelphia, sunny in Pittsburgh and sunny at home but then I figured the delay was caused by the backlog of delays caused by the bad weather earlier in the week. No matter the cause, I was going to be at the airport for an additional 43 minutes – if all went well.

I spent the extra time writing much of what you’ve read so far at a table located at the food court. I had the laptop out, a bottle of Pepsi Zero at my table and the satisfaction that comes with spending one’s time productively.

Confronted by a long wait at Philadelphia International

Airport, Lee Groves – also known as “The Travelin’ Man” – sets up shop following a relaxing meal at the food court.

I also spent some time chatting with a pilot who happened to be seated next to me and when I told him about what I did for a living, he admitted he did not follow boxing – in fact, he said he doesn’t have a TV – but he knew a boxing trainer in Maine who might have heard of CompuBox.

The pilot and I ended our talk mere minutes before my Pittsburgh flight was to board but, as has been the case lately, the proceedings fell further behind schedule. I settled into my window seat in row six, briefly chatted with my seatmate and read a library copy of Kevin Cook’s “The Last Headbangers: NFL Football in the Rowdy, Reckless ‘70s, The Era That Created Modern Sports.” At 7:03 – three hours and three minutes after the original departure time – American Airlines Flight 5297 from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh finally achieved liftoff.

Our plane landed in Pittsburgh 58 minutes later and, thanks to my unfavorable parking space, I didn’t reach my car until 40 minutes afterward. I pulled into the driveway shortly after 10:30 p.m., bringing the curtain down on a long, changeable, productive yet still enjoyable travel day.

My next journey – the last of three consecutive weekends on the road – will take me back to the Philadelphia area, for, on Friday, Andy Kasprzak and I will chronicle the hits and misses for a “ShoBox: The New Generation” quadrupleheader at the 2300 Arena topped by Thomas Mattice-Isaac Cruz and supported by Raeese Aleem-Adam Lopez, Montana Love-Jerrico Walton and Derrick Colemon-Joseph Jackson.

Until then, happy trails!

*

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, West Virginia. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 16 writing awards, including two first-place awards, since 2011. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics” (available on Amazon) and the co-author of “Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers” (also available on Amazon). To contact Groves about a personalized autographed copy, use the email [email protected] or send him a message via Facebook.

Struggling to locate a copy of The Ring Magazine? Try here or

Subscribe

You can order the current issue, which is on newsstands, or back issues from our subscribe page.