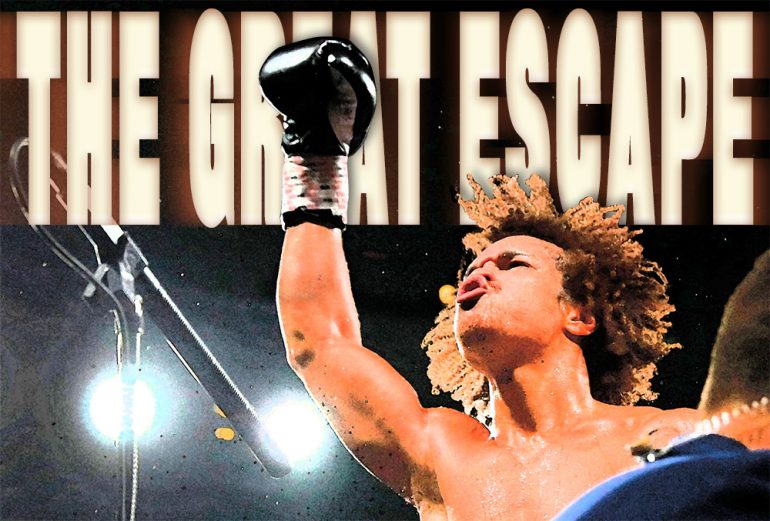

The Great Escape

BLAIR COBBS LITERALLY LOST HIS IDENTITY IN THE CHAOS SURROUNDING HIS FUGITIVE FATHER, BUT HE REBUILT HIMSELF IN THE BOXING RING

Blair “The Flair” Cobbs wasn’t about to do that. He wasn’t about to judge the man seated across from him, because hell knows the man had been judged enough. This time, they weren’t talking on a phone separated by sepia-toned, inch-thick prison Plexiglas. This was more intimate, more visceral, just Blair and his father, Eugene, in the living room of Blair’s three-bedroom Las Vegas apartment, having a deep, cathartic conversation – finally – about a cloud that hovered over both of their lives.

Their eyes didn’t miss each other. There was no tension in the air like before a fight.

They agreed, father and son, that nothing will change the past – and damn, what a past. They agreed, father and son, that they have the present and could have an even better future.

Eugene Nicholas Cobbs, who was also known as Eric Wiggins and Marquis T. Munroe, was sentenced in June 2010 to 151 months in prison, followed by five years of supervised release for his role in a nationwide cocaine conspiracy, ending in an airplane crash in December 2004.

Yes, that Eugene Nicholas Cobbs, the man who was released from a Phoenix-area halfway house on August 28, 2019, after an escape from a minimum-security federal prison in 2013 tacked on additional time to his original sentence.

A hardened man who was seeking forgiveness from his son. Eugene was remorseful for the times he abandoned Blair and his sister, Ashley, and forced them into a life on the run, which led them to Guadalajara, Mexico, where Blair found his lifesaver, boxing.

“Yeah, how twisted it sounds. Who knows where I would be without boxing, and if my father didn’t lead the life he led? Who knows if I would have even found boxing?” admitted Blair, 29, a rangy 5-foot-10½ welterweight southpaw. In his most recent fight, Blair (13-0, 9 knockouts) stopped Carlos Ortiz Cervantes in six on the Canelo Alvarez-Sergey Kovalev undercard on November 2 in Las Vegas, stealing the show with his crazy post-fight celebration.

For once, it was good to know who he was – and is. For once, it was good to know he was on stable ground.

“I was about four or five different aliases when we were living in Guadalajara, but you live and you lie so much, you forget who you were and who you are as a person,” Blair said. “That was a hard lifestyle, to the point where I had to remember all of the lies. Identity early on for me was a crisis. But I was a kid. I didn’t know or care. I just wanted to die. I knew my father had something to do with drugs.

“I mean it. I wanted to find a way out of that life. There were thoughts of it. It wasn’t the worst idea to die, in that particular time of my life, in that particular environment. There was no stability. You think about suicide, just thoughts. It wasn’t the worst idea, because we were dealing with a series of things that could have happened that really weren’t good.”

“There were dark times when I thought there was no reason to go on, and now with boxing in my life, it has saved me.”

Blair, who was signed to Golden Boy Promotions in 2019, a year that saw him win four bouts against solid opposition, was born in Philadelphia on December 30, 1989. He lived with his mother until she shipped him and his sister out to Los Angeles when he was 14 to live with their father. By then, his parents had been separated for seven years. Blair couldn’t believe it. He moved into a luxurious mansion in the Hollywood Hills. He attended Beverly Hills High School. Eugene possessed Bentleys, airplanes, you name it.

Authorities questioned it.

The Cobbs family was living “the life,” yet no questions were asked as to how they were doing it. Eugene never had what could be defined as discernable income. He told local law enforcement that he was a plumber and that the money he accrued was his life savings.

It seemed suspicious.

And gradually, authorities began slowly tightening their circle around Eugene Nicholas Cobbs.

Over the next few years, Blair lost his mother to a crazy circumstance, when she and numerous others died of carbon monoxide poisoning during a party on a yacht. Around that same time, his maternal grandmother died of cancer.

(Photo by Tom Hogan/Golden Boy/Getty Images)

One day arriving home from school in 2004, Blair’s reality became quite different. The mansion was turned over. Law enforcement had ripped through the house, leaving everything disheveled. Eugene Cobbs was gone.

Blair and Ashley didn’t know what had happened.

On December 18, 2004, Eugene took off from Compton Airport in a 1977 twin-engine Piper Aerostar with 525 pounds of cocaine, worth $24 million on the street, on a cross-country run to Philadelphia. He refueled in Blanding, Utah, and then Cameron, Missouri. Attempting to land again in snowy weather, he overshot the runway at Wheeling-Ohio County Airport in West Virginia and ditched the plane in a nearby wooded ravine.

Eugene, who already had a criminal record, walked away unscathed. He threw a wad of cash at a passing Good Samaritan and was dropped off at a motel. Eugene used one of his aliases to check in, made arrangements with one of his minions and got to Philadelphia. From there, now knowing he was back on law enforcement’s radar, he fled to Guadalajara, got in touch with his wife in Los Angeles to get the kids packed and ready, and off they went.

“We just knew it was something bad, and we moved into this small, two-bedroom house in Beverly Hills to finish out the school year,” recalled Blair, who’s known for his over-the-top wrestling persona – complete with Ric Flair’s signature “Woo!” – and untamed hairstyle. “We didn’t even ask questions. My father was gone. My mother was gone, my grandmother was gone and my stepmother couldn’t stand me or my sister.

“A month later, we just left, packing one duffel bag each, and left the country. We got fake IDs and kept going south. I have no clue how it all worked out. But we got to Guadalajara, where we met my dad.”

There, Blair was introduced to boxing through close friend Rodney Pineda.

Pineda, now 29, first noticed Blair playing basketball; he was a rarity – an African-American teenager in Mexico. Something else, Pineda felt, was an oddity: He never went to Blair’s house; they always went to his.

“We busted it up, playing one-on-one, and one day another friend told us about this boxing gym called El Lobo, which was really far,” Pineda remembered. “We went in there the first day and we both found out that boxing is a hard fucking sport. They put us in the gym right away. We found a local gym, and within the first month we were going to both places and sparring pros.

“We grabbed some money from our parents and drove out there at a young age. The cops stopped us and I would ask them how much the ticket was. They would say 200 pesos, which is like 20 dollars. I would pay them right there and tell them I had to hurry because I was late for work. Blair loved it. I remember him hitting the bag and how angry he seemed to be. Blair really found discipline in the ring.”

There’s plenty of room to grow, however. Cobbs is an aggressive, wild swinger, and that can lead to trouble, creating holes in the southpaw’s defense.

“Blair is good right now, but he could be great because of his athleticism and his ability,” said Clarence “Bones” Adams, a former 122-pound titleholder who met Cobbs when the fledgling fighter was living out of his car in Las Vegas and now partners with Brandon Woods as his co-trainer. “But Blair is going to be Blair. He holds himself back. He needs to step back and learn and take our advice. Like the last fight (when he beat Cervantes), he wouldn’t box the way we wanted him to. He boxed the way he wanted to.

“It made us look bad as trainers, like we’re not doing our job. Blair is a phenomenal, fantastic young man, and he’s so athletic. But what happens when the athleticism runs out? We’re trying to prevent that and trying to make sure he does everything properly. Blair has the potential to be great, he really does. I believe in him. He’s very strong and athletic. I just wish he would listen some more.”

One thing Cobbs doesn’t lack is personality. And he’s certainly entertaining. His major disadvantage is that he’s a 29-year-old “prospect.” Time is vital.

Mexico was bad, but when Blair moved back to Philadelphia, it got worse. He found out his father had been arrested by Mexican immigration authorities on December 5, 2008, and extradited to Houston, then brought to West Virginia. A news report let Blair know his father was in custody, which actually turned out to be a relief. “I thought my dad was dead,” Blair said.

Eugene wasn’t through dodging manhunts, though. On April 10, 2013, he escaped the Federal Correctional Institution in Morgantown, West Virginia, and was caught once again trying to enter Mexico a year later. By then, Blair was 3-0 as a pro.

“I don’t know what allowed me to open up to my father again,” Blair said. “It was important to see him there in the crowd (for the Cervantes fight in November). I have no time to hold on to old wounds. Someone like me, I still think something will happen to me, so I got over it with my dad. We had a heart-to-heart and he said he was sorry for all of the things that he’s done. I was able to visit him in jail. It was awesome seeing me work and seeing him there in the crowd. I felt like I was the show, even when Canelo and Ryan Garcia were fighting. I started with my ‘Wooo’ and the rest of the crowd ‘Woooed’ me back.”

Eugene Cobbs didn’t see his son after the fight. Blair was told his father was too emotional to see him.

“There were dark times when I thought there was no reason to go on, and now with boxing in my life, it has saved me,” Blair said. “I don’t know where I would be and if I would be alive if not for boxing. I want to inspire people. And I have to forgive my father. We’re talking; we’re hopefully going to move forward together.

“I always thought my father cared, but we didn’t always have a great relationship. For a long while, I used to think he didn’t really love me. But he prepared me to fight in this ugly world. I have to give him credit for that. With everything I’ve been through, sometimes I feel like I can’t die.”