Mzonke Fana is still the ‘Rose of Khayelitsha’

During a bustling morning in Cape Town, I find myself ringing the doorbell of a Muay Thai Gym on Bree Street. I have often driven past it but never gave it much notice because it doesn’t read “boxing” on the building. Today I am here for an important interview but the ringing doorbell provokes no reaction.

After some minutes have elapsed, two buoyant young men with telltale Eastern-style tattoos come half-striding, half-jogging down the street and stop at the door. They give me a once over and no doubt, noticing my expanding waist line, ask, “Are you coming here to train with us, dude?” I reply that I am here to meet a certain former boxing world champion. Their faces light up. “Oh, you are here to see Mzonke!” one exclaims. “And in this corner, the reigning and defending champion of the world, the ‘Rose of Khayelitsha,’ Mzonke Faaana!” his friend bellows, doing his best Michael Buffer impression.

There aren’t many roses in the thorny world of boxing but South Africa has two. There is the “Rose of Soweto,” the popular former lightweight and super middleweight champion Dingaan Thobela and then there is the Rose of Khayelitsha, the two-time IBF junior lightweight beltholder Mzonke Fana. Both are named after from where they came, in Fana’s case Khayelitsha, one of the townships surrounding the actual city bowl. Cape Town has never been known as a boxing hotbed although there have been some popular fighters over the years. Slam-bang welterweight Gary Murray held a fringe title and Nika Khumalo twice came close to beating WBO welterweight titleholder Manning Galloway, with two split decisions not going his way. Fana remains the only champion from Cape Town, when you narrow it down to the four recognized sanctioning bodies.

The Muay Thai dudes don’t have a key and the gym owner finally arrives to open for us. “Just hang around; Mzonke will be around any time now,” he informs me. I receive a message on my phone from the champ telling me he is on his way. In Africa, time often passes in big seconds and I happily settle myself on the ring apron while I go through my notes. It is your typical crossover gym, popular among the twenty-somethings these days. There are some exercise mats and a variety of bags and kettle bells complementing the ring and various posters of Muay Thai events adorning the walls.

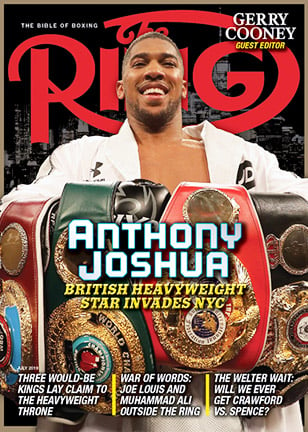

Join DAZN and watch Joshua vs. Ruiz on June 1

Fana enters the gym with that grace of a dancer typical of many fighters, his teenage daughter Buhle, dressed in her school uniform, in tow. Neatly dressed in a red sport shirt and cap topped off with dark-rimmed spectacles, he resembles an upmarket personal trainer, which, I assume, he probably is these days. After the exchange of social niceties, Buhle wanders off in typical disinterested teenage fashion while we start our interview.

His first love as a kid was soccer but his friends’ sport of choice was boxing. “Most of my friends were boxers. I was a soccer player. One day, I followed a couple of them to the gym.” That was back in 1985 in Khayelitsha and a long amateur career followed. Turning pro was surprisingly not on top of his mind. “My coach, in fact, forced me to turn pro in 1994.”

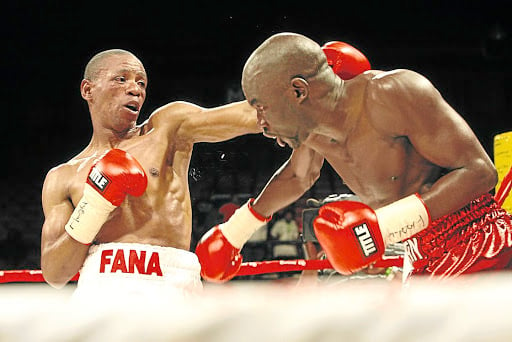

Mzonke Fana (left) vs. Cassius Baloyi. Photo credit: Antonio Muchave

His pro debut was against his stablemate and fellow debutant Siyabulela Manikevane, which he won on points. After running up eight straight victories, the challenged Mkhuseli Kondile for the South African junior lightweight title in 1997 but came out on the wrong end of a split decision. Sixteen months later, he got another chance, this time for the vacant title against Matthews Zulu and took the decision.

Over the next four years he made seven successful defenses of the title and not just against anyone, he is quick to point out: “All of them (title defenses) were against number one contenders.” The national title was a big deal back then, a hurdle you mostly had to cross if you were going to challenge for world titles. I remember those fights well, since I watched all of them. There was the dangerous Sakhumzi Magxwalisa, who would go on to win a minor belt in Thailand, then had two bouts against highly-touted amateur star Irvin Buhlalu and a war against Wiseman Jim. He kept hanging onto his belt and then there was also a victory over then-undefeated and future three-time lightweight title challenger Ali Funeka. I ask Fana about him. “Ali Funeka as well as Irvin Buhlalu were very tall for their weight. First round, Funeka caught me with a hard right and I went down. I got up and won the fight,” he shrugs. Why did the very talented Funeka never win the big one? “I don’t know. Sometimes you must have the right opponent at the right time. I think he just had bad luck,” he opined.

Between defending his national title, Fana also dipped his toe into the international pond. In his first try, he dropped a 12-round decision to Dean Pithie in England for a WBC international title, in December of 1999. He took that as a learning experience. “I lost but not badly. Remember, after all my losses, I went back and won those titles,” said Fana. That would be his last loss for a long while and he recorded several wins against international opponents, which culminated in a WBC final eliminator against undefeated 21-0 Filipino Randy Suico in 2004.

A war ensued. “What a fight,” he remembers, shaking his head with a whimsical smile. “He dropped me in round two and again in round four.” Fana got up each time and simply continued to box, using his skills to bank enough rounds to win a split decision, to the delight of his supporters. A world title shot was finally on his doorstep.

There was only one problem: At the time, the WBC titlist was Marco Antonio Barrera. It didn’t turn out well for Fana. In the second round, Barrera landed a flush left hook. Fana went down hard and referee Laurence Cole waved the fight off without a count. Did the magnitude of the occasion simply get to him?

Fana is adamant that it did not, “I was ready, well-prepared for the fight, until that round. I think my mistake was to take my eyes off my opponent. Barrera caught me almost below the belt. When that punch landed, I looked at the referee and (Barrera) caught me right after that.” Fana was widely expected to use his jab and movement to box the Mexican star. Instead he seemed quite unintimidated and willing to trade. I ask him about that. “In my mind, I was thinking that he was expecting me to jab and move and I decided to switch it up: box, fight, box, fight,” he stated.

Afterward, predictably, the consensus was that he had been shown his place in the pecking order: a solid national champion and fringe contender, nothing more. Fana, however, was as steadfast as they came and stoically soldiered on. Two international wins and he was a mandatory challenger once again, this time for the IBF version of the world title.

Here is where things got interesting: Countryman Cassius Baloyi had won the belt, which was previously owned by another South African great, Brian Mitchell, by stopping Manuel Medina in the United States. Baloyi then unexpectedly lost it to unheralded Aussie Gairy St. Clair. They were going to have a rematch; Baloyi got injured and St. Clair, in turn, dropped the belt to last-minute substitute South African featherweight champion Malcolm Klassen, who jumped up a weight division for the unexpected opportunity. This was the start of a time period that saw South African fighters play musical chairs with the IBF junior lightweight strap.

Fana liked his chances from the get-go, “(Klassen) was a young man fighting at featherweight. I didn’t even know how he got to junior lightweight and suddenly he is a world champion.” In the build-up to the fight, there was a lot of pressure heaped onto the shoulders of the Rose of Khayelitsha. The general opinion was that if Fana didn’t prevail in his second title shot, which was held right in his backyard, in April of 2007, then boxing in Cape Town was truly dead.

Klassen was far from an easy touch however. In a nip-and-tuck affair that ebbed and flowed between the aggressive, swarming Klassen, with his trademark body attack, and the smooth boxing Fana, with his accurate jab, movement and straight rights, Fana edged a split decision and was finally a world champion. He gives props to his opponent: “He fought well, very tough guy that Malcolm Klassen.”

Fana successfully defended the title with a ninth round stoppage of Javier Osvaldo Alvarez four months later and then came a mandatory defense against Baloyi. It was not Fana’s night. He struggled with his taller opponent and, for a change, he was the one stuck at the end of someone else’s jab. “Baloyi had a very good game plan. I was well-prepared but, in that particular fight, he turned into a jabber. He jabbed me all night long,” Fana admitted. Despite losing a majority decision and his title, he learned from the loss and remarks that sometimes giving one’s opponent his own medicine works out.

Baloyi’s second championship reign didn’t last much longer than his first. In his second title defense, he was completely outfought by a fired-up Klassen, who battered him to a seventh round stoppage defeat to regain the title, in April of 2009. I ask Mzonke whether he was surprised by the dominant nature of Klassen’s victory. He nods, “I was expecting Malcolm to beat Baloyi but not by knockout.”

In turn, Klassen ventured Stateside and lost the title to Robert Guerrero, four months later, while both Fana and Baloyi kept winning. When Guerrero ventured all the way north to welterweight to chase the Floyd Mayweather Jr. sweepstakes, Baloyi and Fana were matched for the second time to contest the vacant title, in September of 2010.

Fana appeared reinvigorated and his trademark jab was on target, as he steadily outhustled a bewildered Baloyi. “I did things totally different for this camp. I had good preparation, working with trainer Gert Strydom and it worked. I out jabbed him this time and beat him easily,” Fana beamed. He won by a wide margin on all the cards, and two years after losing the title, he was once again the IBF junior lightweight titlist.

It should have been a time to bask in the glory and cash in on some well-deserved paychecks. Instead it kicked off a dark period in his career which saw Fana stripped of his title for not making a mandatory defense against Argenis Mendez. He clearly doesn’t like to dwell on it but offers an explanation: “My promoter (then Branco Milenkovic) was supposed to negotiate on my behalf for the purse money. He seemed to negotiate for the challenger instead and when I didn’t agree with him on my purse, that is when the trouble started. Then he gets it into his head that I am not ready to fight.” Fana remains adamant that this couldn’t have been further from the truth and he was simply not in agreement with the money on offer, expecting it to be thrashed out in the negotiating process. Instead he was surprised when his promoter petitioned the IBF to postpone the fight. “It was not a week after that and then I heard I was stripped of the title.”

After almost two years out of the ring, Fana returned in 2012 but his form was never quite the same. He fought on for another five years with mixed results. There was a decent win over former IBF 122-pound titlist Takalani Ndlovu; he won another South African title at lightweight, reversing a previous defeat to Sipho Taliwe in the process and added various sanctioning body regional belts to his trophy case. On the flipside, there were also losses to Paulus Moses, Xolisani Ndongeni and Emanuel Tagoe, as well as a wide decision loss to Terry Flanagan in a challenge for the WBO lightweight title, in July of 2016. He finally retired in 2017 with a record of 38-13 (with 16 knockouts).

I ask Fana what he’s up to these days. “Nothing!” he exclaims, laughing before checking himself. “I am helping here in the gym. I just help out any boxer that needs my services.” I ask him how it feels to have been the only big-name boxer from Cape Town for such a long time and being part of a legendary South African rivalry. Fana replies, “It is something special but I look forward to seeing another boxer from Khayelitsha become a two or even three-time world champion. If I can play a role in their development, it would be good. I would love to be a part of that.”

Mzonke and Buhle Fana. Photo credit: Droeks Malan

There are some incrementally positive changes happening on the Cape Town scene with a few emerging prospects like Thembani Mbangatha, Lunga Sitemela and Emile Kalekuzi headlining club shows, so I ask Fana if he has any advice for the up-and-comers. “They should keep themselves grounded, stay focused and respect themselves,” he offered. “Discipline and dedication are the keys in boxing and life in general. Stay who you are today; don’t become big-headed. Training is the most important thing. You can be clever; you can be talented but if you are not training, it all falls apart.”

Buhle pops in to let her dad know that he needs to take her somewhere. I convince her to pose for a photo with her old man before we end our interview. Outside again, I watch them get swept up by the foot traffic and am reminded that even world champions have to deal with the pressures of everyday life.

Will the Mother City sprout another rose among the thorns? Only time will tell.

Struggling to locate a copy of The Ring Magazine? Try here or

Subscribe

You can order the current issue, which is on newsstands, or back issues from our subscribe page.