Best I Faced: Armando Muniz

Mando Muniz was a popular welterweight and four-time world title challenger during the 1970s.

Born Armando Muniz in Chihuahua, Mexico, on May 3, 1946 he was the second eldest of eight children. His family decided to move to America for a better way of life when he was just five years old. Muniz’s father worked for an American company that was building the American Highway from El Paso to the south of Mexico. They eventually settled in the Los Angeles area.

Muniz liked boxing from the age of 12 and regularly watched on television. As a youngster he saw an advert in the local paper for the Golden Gloves and decided to apply without his parents knowing. He duped his mother into signing the required papers, letting her think the documentation was for school. At the time you had to be 14 years old to enter but Muniz was several months younger and lied about his age.

“I lost my first fight,” Muniz told The Ring. “I hadn’t had any training whatsoever. I did some running and made a heavy bag at home. The only thing I lacked was sparring and maybe coaching [laughs].”

Muniz had found his niche and went on to win several national titles, all the while attending Cerritos junior college from 1964-66 as part of the wrestling team.

Muniz flanked by Sugar Ray Robinson (left) and Muhammad Ali (right). Photo courtesy of Armando Muniz

When he began school in 1967 he was trying to keep his student deferment so the he could finish school before being drafted into the U.S Army.

“At that time the Vietnam War was very intense so I was scared of being drafted,” he admitted. “Wrestling season was usually from October to January so I would stay involved with my amateur boxing endeavors to make sure I would be ready.

In February 1968, Muniz won the western regional Olympic trials in San Francisco. That qualified him to fight at the Olympic trials in Canton, Ohio, in the August. However, he had a sizeable problem to overcome first.

“It dawned on me that I was not a U.S citizen yet” he said. “In the March I applied for citizenship and passed the test easily.

“Reality sort of set in when I got a letter from the Department of the U.S. Army congratulating me for being drafted in to service. I had to report for duty on July 16. At that time my wife and I had been engaged for almost two years. We ended up quickly planning our marriage for July 6 and I was determined to take her on our honeymoon to Delicias, Chihuahua. We got back on July 14 just in time to report for duty.”

A 22-year-old Muniz went on to reach the quarter-finals of the Mexico 1968 Olympics before leaving the army on June 15, 1970. He exited the amateur code with a record of roughly 58-6.

“I had always wanted to be a college graduate and I didn’t think I would get a chance to finish college being in the army,” he explained. “I had fought as an amateur and I was already 24 years old. (Ever) since I was a kid I wanted to be like Emile Griffith, a Carmen Basilio, like Floyd Patterson. I had that in my mind and I thought if I don’t do it now, I won’t do it later. I wanted to say I fought pro at the Olympic Auditorium which was the center of boxing in California.”

Muniz registered at the California State University in Los Angeles and graduated the following year with a BA. He continued at school until he achieved his teaching credentials and stayed for his Masters degree.

During this time, Muniz had begun his professional boxing career. He moved quickly and after just 16 months stopped the vastly more experienced Clyde Gray to become the NABF 147-pound titleholder.

Muniz (left) at war against Emile Griffith. Photo by The Ring Archive

In his very next fight he took on future Hall of Famer Emile Griffith. The former champion used all of his experience and know-how to outpoint Muniz, handing him his first loss. It was a painful lesson.

“I think Emile took it easy on me in that fight,” revealed Muniz of the January 1972 encounter. “He already had 80-something fights and had been world champion five times. I was stepping up and I might have gone too early.”

Over the next few years, Muniz lost a few more times, notably to two-time former junior welterweight champion Eddie Perkins and future 147-pound titleholder Angel Espada. He remained in contention, however, with victories over Ernie Lopez and Hedgemon Lewis. The latter positioned Muniz for a welterweight title shot against Jose Napoles.

“El Hombre” traveled to the country of his birth, challenging Napoles in Acapulco in March 1975.

“I wasn’t tactical like him,” Muniz said. “That fight, I was in the best shape of my life. As the fight wore on I was getting hit, but I was trying to be the aggressor. In the 10th round he got a little cut over the right eye and my manager told me to target it. I fought more aggressively and he started fighting dirty.

“The doctor came in and said the fight needs to end and his corner persuaded the commission to let Napoles continue. We went into the 12th round and he started throwing low blows, it was incredible. They stopped the fight and I thought I’d did it. I went to the corner and the referee, who I heard was compadres with Jose, announced Napoles had won. The announcer had refused to call the scorecards and walked out.

“I look up to the sky and go, ‘Why me? Why me? What did I do?’

The controversy in fight one led to a direct rematch four months later in Mexico City.

“He stayed away a little more, he was more careful and I guess he trained a little bit more because he wasn’t as tired,” Muniz said. “He knew he was in a fight. In the eighth round I got caught by a left hook and the next thing I know the referee is counting, ‘four, five…’ I got up and thought, ‘Now I’m going to kick your arse.’ I settled down and fortified myself.”

In a bloody affair, Napoles dominated with the jab to win a hard-fought 15-round decision.

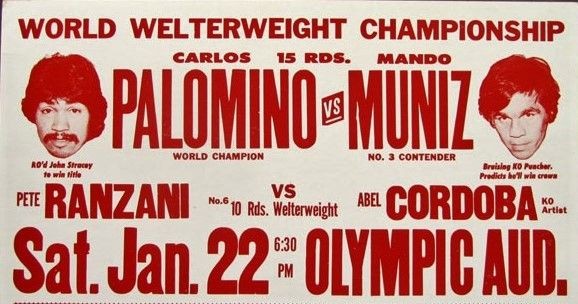

Following that setback, Muniz won four fights in 18 months to earn a third opportunity, this time against Carlos Palomino in January 1977.

Following that setback, Muniz won four fights in 18 months to earn a third opportunity, this time against Carlos Palomino in January 1977.

Both men touched down in a close fight but it was Muniz who was heartbreakingly stopped with just over 30 seconds left in the 15th and final round. The fight had been evenly poised on the scorecards, with two officials having each man up narrowly and the third having the bout level.

“It could have gone either way,” Muniz said. “I was totally aware in that fight. I wasn’t hurt, I looked at the clock and told the referee, ‘Please let it go’ but he stopped the fight.”

Muniz had to wait 16 months for a rematch with Palomino who, this time, won a unanimous decision.

In the fall of 1978, Muniz was offered the opportunity to face rising superstar Sugar Ray Leonard.

“Real quickly I found out I have the energy, the guts, but I don’t have the speed and it’s not there anymore,” acknowledged Muniz. “That thing that makes you want to fight, I didn’t have it anymore.”

The former four-time world title challenger retired after being stopped for only the second time in his career (in Round 6).

“I felt embarrassed, how could I let this happen,” Muniz asked rhetorically. “On the way home I just said, ‘This is it.’ I promised my wife I would do it when the time was right and I wouldn’t fight any more than I had too. I didn’t want to end up like other fighters who end up being hurt.”

His final career record was 44-14-1, 30 knockouts.

Muniz later appeared in an episode of popular sitcom Taxi as well as the 1980s movie Midnight Run.

He put his previous hard work in college to good use as a teacher at Rubidoux High School in Riverside, California, where he taught mathematics and Spanish. He was also the wrestling coach for over 20 years before retiring in 2008.

Muniz has been married for 50 years, has three children, five grandchildren and enjoys being part of the community.

He graciously took time to speak to The Ring about the best he fought in 10 key categories.

BEST JAB

EDDIE PERKINS: Oh gosh, it would be between Emile Griffith, Jose Napoles, Eddie Perkins and Angel Espada. Emile had been doing it so long, he knew the jab would land. He was near over-the-hill, but he still had a great jab. Napoles’ jab was different in that it was as good as a right hand punch; it was almost a power punch, you could feel it. He developed that over the years. Eddie Perkins was a boxer who could handle you in many ways and one of them was with the jab. Perkins was a hard guy to catch; his jab kept him away, I followed him all over the ring, he had the jab and did good. Like an idiot I didn’t stop and try to figure it out. Espada was very shifty, but along with that he’d throw a jab and catch you all the time, he wouldn’t be there when the jab was thrown. I’d say Perkins had the best jab; he figured me out real quick and carried me. I was always on top of him, trying to get in there, but his jab was always stopping me.

BEST DEFENSE

SUGAR RAY LEONARD: Sugar Ray Leonard maybe; I couldn’t find a place to hit him. He had a good defense. It was tough to realize in the middle of the ring that I was being used as a stepping stone and how nice it must be to have the networks, promoters and the whole system of boxing behind you. He moved around pretty good. He was very fast, he had a fast jab, fast right hand, he moved around, back and forth.

FASTEST HANDS

LEONARD: Leonard would be one of them for sure, Angel Espada was pretty good; he was a helluva boxer. When I fought Clyde Gray for the NABF welterweight title, I only had 16 fights. He had more knockouts than I had fights and I knocked him out. He threw jabs and real fast punches; at one time he was pretty good. I have to say Sugar Ray Leonard. It was a blur but I have to say when I fought Leonard I was near the end so everything would seem fast [laughs].

BEST FOOTWORK

PERKINS: Leonard, Clyde Gray and also Eddie Perkins. Perkins was an accomplished boxer; that’s why he became a champion, and I would include Jose Napoles. I’d have to say Eddie Perkins. He was hard to hit and the reason was because he was never there to be hit.

BEST CHIN

RUBEN VAZQUEZ ZAMORA: There was this little Middle-Eastern guy [Eltefat Talebi] I met when I was coming up. I know he was put there for me to win, but I was hitting him and I was like, ‘Jesus Christ, I’m going to kill this guy.’ I hit him so hard. There was another kid I fought twice from Mexico [Ruben Vazquez Zamora]. This guy took punches galore. I’d hate to see him now because I hit him hard and he had a lot of fights. And how many fights did he have with guys like me? Other guys that took a punch real well, Oscar Albarado for one, [Ernie] “Indian Red” Lopez, he finally withered down. Napoles wasn’t too bad, he took a lot of shots too. Ruben Vazquez Zamora could take a shot like a son of a gun, oh my God!

SMARTEST

JOSE NAPOLES: He had a knack of being right next to you, he would slip and you could not hit this guy. Next to Napoles was Eddie Perkins and Emile Griffith, they had their trade down crazy. I thought I could do it good, but I guess I couldn’t do it as good as them.

STRONGEST

EMILE GRIFFITH: I have to say probably because of his experience, Emile Griffith. That is the one I can remember being physical. (Ernie) Lopez worked his career as a carpenter and he had strong arms.

BEST PUNCHER

ANGEL ESPADA: Angel Espada when I fought him. He was the boxer and I was coming at him, he’d hit me and I’d go, ‘Son of a Gun, I’ve got to watch out.’ But I kept doing it. I’d say Espada, he made your whole body shake.

BEST OVERALL SKILLS

NAPOLES: I’d say Jose Napoles; he was well-trained, he had everything, he could slip and slide, jab, uppercuts. I’d say Jose Napoles was the No. 1 guy as far as boxing skills.

BEST OVERALL

NAPOLES: He had real fast hands, slippery, he was an excellent boxer. He had supreme vision, that’s why they called him Butter Man, ‘Mantequilla’.

Questions and/or comments can be sent to Anson at [email protected] and you can follow him on Twitter @AnsonWainwright

Struggling to locate a copy of The Ring Magazine? Try here or

Subscribe

You can order the current issue, which is on newsstands, or back issues from our subscribe page.