A glorious run: Jim Lampley recalls his career with HBO Boxing

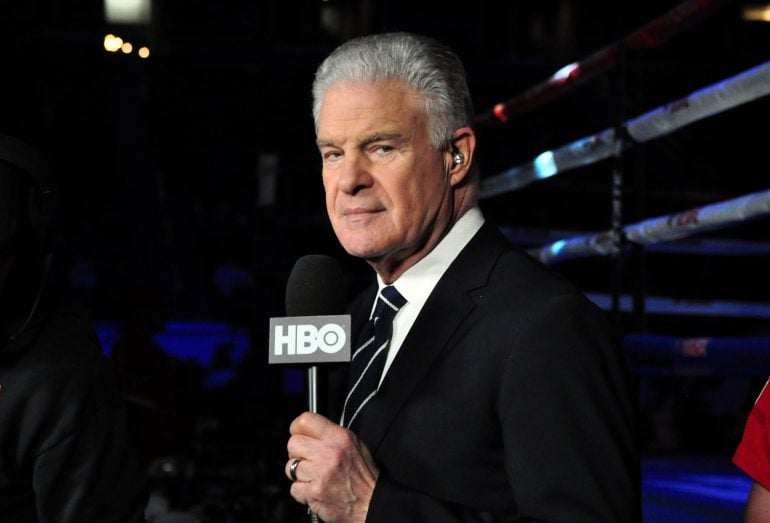

HBO Boxing hung up its gloves on Saturday night, and Jim Lampley, the hall-of-fame broadcaster who has become the voice of the subscription cable network over the past three decades gave it a proper eulogy after the final bell and post-fight interview.

“Here at HBO Boxing, the end has come. We thank you for watching. We urge you to turn elsewhere, to continue your support of this purest and most human of all competitive sports. Most of all, we thank the people who poured forth their bodies and their souls to write our 45-year history in the ring: The Fighters. They are uniquely precious, and the life lessons they provided for us are timeless and indispensable.”

It goes without saying who articulated the final send-off, because his voice is synonymous with HBO Boxing. It also goes without saying that he got emotional. For the past 30 years, Lampley has been that embodiment as the blow-by-blow commentator for the network, and if there was ever a wonder of what drives his sentiments, all one need do is disregard the facade and truly listen to what he’s trying to say.

A little more than 24 hours before the final broadcast, Lampley had just conducted his final pre-fight interview at the host hotel near LAX. Every hotel conference room looks the same, but it is in these rooms around the globe that Lampley has succumb to the wildly different stories over the years, only to relay those emotions before, during or after the fighters leaves a piece of themselves in the ring.

“The world comes and sits and front of me, and then, the following day, I go to the arena and they show me their arts,” Lampley told RingTV.com, holding back tears, even with just one writer in the room. “They take off their clothing, and eventually – to a certain degree – they take off their skin, and they show you everything about them, inside and out. There is no other sport that reveals people the way this one does.

“One thing I like to say to myself and to others is that I have seen and heard the whole world through boxing, sitting in these rooms, talking to these people. What an incredible privilege.”

Cecilia Braekhus – the undisputed female welterweight champion of the world – was the last subject, and the closing main attraction of a legacy that started with George Foreman vs. Joe Frazier on January 22, 1973, a tape-delayed heavyweight championship from Kingston, Jamaica billed as the “Sundown Showdown.”

“From a sort of textbook standard it feels inappropriate, but within the context of everything that we’ve experienced it feels appropriate,” Lampley said about the final card, which featured two females and a Mexican super flyweight. “It’s a portrait of a changing world and, to a certain degree, everything we’ve done for 45 years was a portrait of a changing world. So, it’s kind of fitting, that the last telecast we do is something that we do for the first time. There had been a whole lot of those. There’d been so many firsts and onlys in HBO Boxing’s history, in my career, etc., etc., that it’s absolutely appropriate that the last thing we do is something that we haven’t done before.”

Lampley wasn’t there for the first 15 years of HBO’s glorious run. He was well into an established broadcasting career at ABC before signing a contract with HBO in 1988. During the course of the previous 13 years, Lampley had rose from being a feature reporter to a key figure in bi-yearly Olympic coverage to a studio host for ABC’s “Wide World of Sports” and the same designation for the most prominent college football programming at the time. Lampley even called boxing for ABC, but not until later in his tenure thanks to a thought-up glass ceiling constructed by the ego of Howard Cosell, who dominated telecasts by himself ringside without need or want of another along with.

“I had it in my head that if I even mentioned the word in the building, I would be beheaded,” Lampley recalled. “I had purposely stayed away from boxing and never had anything whatsoever to do with it until the summer of ‘85. I went to an in-house, private, network screening of Hagler-Hearns. I stood next to the executive who was in charge of the boxing telecast in house – a guy named Alex Wallau – and we talked boxing for those three rounds, and at the end of the three rounds, he turned to me and said, ‘Jesus. You know a hell of a lot about boxing, why have you not sought to be involved in this telecast?’ I just kinda gave him a blank look like, ‘C’mon, why do you even ask that question – you know the answer to that question.’”

Eventually, Lampley did get tabbed by Wallau to call fights for ABC, and the experienced gained, along with the relationships he built, were viable toward getting hired by HBO. One such affiliation was having called a few early fights of Mike Tyson on ABC, before the teenage heavyweight sensation became the youngest champion ever, and seemingly took over the world. It was no coincidence Lampley’s first call on HBO was Mike Tyson’s second-round destruction of Tony Tubbs in Tokyo, Japan on March 21, 1988.

Tyson at his peak. Photo by THE RING Archive

“It was very appropriate,” Lampley said about his HBO debut. “Because I was conscious that when I had signed a contract to do boxing for HBO, replacing Barry Tomkins, that what HBO was buying, to a certain degree, was my link to Mike. The fact that I had done Mike’s first several network television exposures at ABC, and there was already a base from which a certain percentage of the audience could link my voice, my style, my calls, to Mike Tyson from those exposures at ABC.

“I was known commodity. I was a pro with a big background, and if you go back and look at the very first on-camera I did with Ray Leonard and Larry Merchant – ringside in Tokyo – my hand shook on the microphone. And my hand shook so visibly that the director Marc Payton had to tighten the shot so that it would not be distracting to viewers that I was so nervous. When I look back later thinking, ‘Oh my God, how in the world did that happen? What in the world was it that caused me to be so nervous at that moment in my career after everything else that I had done?’ It was about HBO. And it was about the reverence that I felt for this network – not just relative to sports – but relative to everything that this network did and also relative to boxing, and my place in boxing. I knew that I had, in my own personal view, graduated to another level. I don’t believe in 44 years of on-camera network television work that it ever happened any other time, but that day, my hand shook.”

With his dream job in hand, Lampley eventually got over those jitters and proceeded to narrate a glorious run on HBO, where the network would eventually become the gold-standard in boxing production, if it wasn’t already. Several different eras and precedents on HBO Boxing came and went, and when asked to point out his favorite time on the network, Lampley couldn’t just pick one after pointing out the obvious.

“It’s hard to resist the glamour of the Tyson Era, and the education and the cognitive reality of the dissolution of the Tyson Era,” Lampley said. “The dissolution of that era and the destruction of his glamour forced people to recognize boxing is a sport about styles. Both competitive styles and human styles. There were certain things that Evander and Lennox had that Mike would never have, just as he had certain things that they didn’t have. I think it was all a big learning process for the audience if you paid attention, as the fighters certainly did, to what was going on during that period. But I also loved the

Barrera vs. Morales I. Photo by John Gurzinski/AFP/Getty Images

evolution toward greater and greater understanding and exposure of Latino fighters. What went down between (Marco Antonio) Barrera and (Erik) Morales, and later Juan Manuel Marquez, those are amazing stories that taught us a great deal about life and about boxing. I loved, even though a lot of people were resistant to it, I loved the rise of the Eastern European fighters. I remember when the political change came, and the wall came down and the Soviet Union collapsed in the early ‘90s, I told many of my friends, ‘Wait 20 years and you will see a huge wave of Eastern European fighters because boxing follows poverty, and that’s what’s going to happen here.’ Sure enough, it happened just the way I explained it and just the way I laid it out to people, and everybody thought at first that meant Russians, and for a longtime people insisted on calling Ukrainians or Poles, Russians because they were from Eastern Europe. Then I think everybody gradually got more educated and understood the cultural differences among those people as well and we all got a little bit smarter and learned from that. The whole thing fits together for me, and it’s hard for me to separate out one era and say, well this is a distinct era that I loved during HBO Boxing, because I loved it all, and I loved everything we learned from it.

“It was global, it was all encompassing, it was every culture in the world, it was every kind of person, and I can’t separate anything out from that. It’s all the same experience to me.”

As for HBO’s crowning achievement over the years, Lampley was humble before stating the obvious.

“I think it would be way too self-glorifying to say that we did anything groundbreaking, other than simply to utterly immerse ourselves in the sport, and in the human values of the sport,” he said. “I think that we, because we had no commercials, because we stayed on the air between rounds, because we had time as much as we wanted to create feature pieces and develop profiles, etc., that we were able to cover the sport much more extensively than commercial television ever had. I think one of the things you’re seeing in this transition into a new way of distributing the sport to the audience is, that people don’t realize it until they see it, but when they watch a telecast go away between rounds, they realize they’re missing something. They’re missing a part of the story that became a continuing and very meaningful part of the story during all the years when people consumed mostly from HBO and Showtime. Because on HBO and Showtime, you didn’t go away for commercials, you stayed there, and you followed what  happened between rounds, and those people who are so vitally important to the personality imprint of the sport – the trainers, the cut-men, everybody whom you see in the corners in between rounds – they all became characters. And that makes it a far, far richer narrative than is the case when you’re seeing three minutes, going away for a minute, and then seeing another three minutes, and you don’t know what conversation took place. So, I think we introduced a certain depth and breadth to the audience in the way that we covered the sport, and we focused on humanity. We focused on personalities, and all of that was vital to people’s understanding of what I always say is the most human of sports. The one that will most rip off whatever facade you’ve created and show the world who you really are.”

happened between rounds, and those people who are so vitally important to the personality imprint of the sport – the trainers, the cut-men, everybody whom you see in the corners in between rounds – they all became characters. And that makes it a far, far richer narrative than is the case when you’re seeing three minutes, going away for a minute, and then seeing another three minutes, and you don’t know what conversation took place. So, I think we introduced a certain depth and breadth to the audience in the way that we covered the sport, and we focused on humanity. We focused on personalities, and all of that was vital to people’s understanding of what I always say is the most human of sports. The one that will most rip off whatever facade you’ve created and show the world who you really are.”

In reverting back to the underlying theme, Lampley would immediately say that last part was the thing he loved most about boxing. More than anything, his career in the sport has been an education as much as it was a fascination. When confronted with the idea of HBO Boxing going the route of the typical aging fighter – announcing its first retirement before clambering back into the ring to no one’s real shock – Lampley wasn’t quick to use that word. Just another something he’s learned over the past few decades, and it happened to be from the first fight he ever called, one which none of the public got to hear.

“It would surprise me – I will stay away from the word shocked,” Lampley answered about the idea of HBO returning to boxing. “Long ago I got rid of being shocked by boxing. It’s funny because I mentioned to you that – back at the beginning – the first thing ABC did was to say, ‘Okay we want you to call a fight into a tape machine – call it in a can – to show us that you can be a credible fight caller.’ I went down to Atlantic City alone. I think this is January of 1986, and I went to Atlantic City by myself, and into a tape machine I called a fight that Wallau had picked – a heavyweight fight between Smokin’ Bert Cooper, who was a rising unbeaten prospect at that moment, and a journeyman named Reggie Gross. Alex explained to me before the fight that Cooper was the heavy favorite and Gross was cast in the role of the opponent, and even though Gross was bigger and might look as though he had an advantage cause he was bigger, and Cooper was better and faster, etc., etc., and I should understand that most likely the fight was going to be dominated by Bert Cooper. Sure enough, for the first eight or nine rounds, Bert Copper batted Reggie Gross around the ring like a tennis ball. Then in the last round, Reggie Gross landed a pretty good right hand on the ear of Bert Cooper, and Cooper turned to the referee and quit. Shocked doesn’t even begin to describe. I’m sitting there saying, ‘What!? This makes no sense at all’ – Bert Cooper has dominated the first nine rounds, obviously winning them all – Reggie Gross lands one punch and now Cooper has quit. Later I learned that Cooper had massive personal problems that were ultimately going to get in the way of being the successor to Joe Frazier, which is what he looked like because he was a smaller left-hooker with power. Reggie Gross never did anything of meaning in the sport, other than to land that one punch, and I learned that night, something that Larry Merchant would harp on years later: Theater of the unexpected – don’t be shocked by anything. It was a tremendous lesson to learn that first time. So, then I went from there, to Glens Falls, New York – February 16, 1986 – to call my very first fight between Mike Tyson and Jessie Ferguson. Tyson struggled a little bit in the first few rounds, and then I think it’s round five when he lands a tremendous uppercut on Ferguson, and then he knocks him out. Famously in the post-fight interview with Wallau, Alex asks him something about the uppercut, and Mike says, ‘Cus D’Amato taught me that the purpose of the uppercut is to knock the opponent’s nose bone into his brain. And I was trying to knock his nose bone into his brain.’ I’m sitting there at ringside like – ‘Oh my gosh.’ Alex throws it back to me and I sign off, Wide World of Sports goes off the air, and I had a brown leather portfolio, and that portfolio was sitting on the table in front of me at ringside. As I got up and got ready to leave, I reached for the brown portfolio and I saw something sitting on the middle of it, that at first I took to be a strawberry. And I’m like – ‘Why is there a strawberry on my leather portfolio?’ Then I looked closer and I realized that wasn’t a strawberry, that was the inside of Jessie Ferguson’s nose. Gelatinous material, blood, maybe some flesh, all from the inside of Ferguson’s nose, landed right in the middle of my portfolio at the end of that first fight. That was the other reminder – going along with what happened in Atlantic City – never to be shocked by anything I saw in a boxing match.”

HBO’s final live boxing broadcast featured the reuniting of hall of famers Larry Merchant and Jim Lampley.

Lampley’s sign-off on Saturday night didn’t go without thanking the long list of people he’s worked with over the years, and he couldn’t help but smile all the way through an interview with Larry Merchant, who made an appearance on the telecast for the occasion. Just after the one-on-one interview in the L.A. conference room concluded, Lampley casually mentioned he was hoping not to cry the next night and did so while wiping the already-dried tears on his face that flowed minutes earlier. He was worried about the last four names of his thank yous putting him over the edge – prominent figures who were no longer with us – and sure enough, Lampley got choked up during that part, which led into the last portion announcing that the end had come.

Befittingly, in his case, Lampley’s final call on HBO’s final night came 28 years to the day Tyson last fought on the network. The triple-header came and went without event or fanfare, even in an outdoor venue that seems to conjure up drama in virtually every boxing card it hosts. There was barely a crowd there at Stub Hub Center in Carson, California, on a cold, cloudless night where another boxing card on another network overshadowed it. It was abundantly clear in the surroundings that their time was up, and after the live broadcast ended. Lampley raised an arm in the air while getting an applause from the small crowd of people gathered around the HBO set-up. He said he was merely waving to the crowd, but it was almost as if, for once, Lampley – the representing figure of HBO Boxing – basked in the glory just like any fighter would. Perhaps that was another fitting notion to end it all, because just as those fighters would reveal themselves organically, Lampley would follow suit ringside, unmasking himself in the heat of their moments.

***