The IBHOF Class of 2019 – How I voted and why: Part two

In Part One, I detailed my thought process as I considered the ballots for Non-Participants and Observers for the International Boxing Hall of Fame’s Class of 2019. In this installment, I tackle the even more difficult task of determining which names I will check for the Old-Timers and Moderns.

As is the case with all ballots, voters are allowed to use a maximum of five checkmarks but are not obligated to use all of them if he or she feels there aren’t enough deserving candidates. That’s what I ended up doing on the Old-Timers ballot, which, this year, lists fighters whose careers ended no earlier than 1943 and no later than 1988. (Next year we will consider fighters whose careers ended no earlier than 1893 and no later than 1942.) In the end – as was the case when I voted on this ballot two years earlier – I believed only two fighters rose to the standard I set: Onetime featherweight champion Davey “Springfield Rifle” Moore and longtime 115-pound titlist Jiro Watanabe.

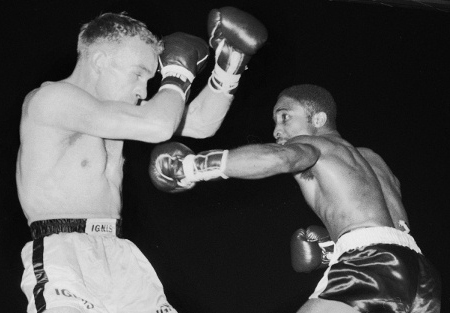

Why did Moore make the cut? That’s a good question considering that Moore accumulated only five successful title defenses at featherweight, a division that boasts many titlists with far larger totals. Normally such a low number would remove him from my radar but Moore’s case was unique. First, Moore passed the “eye test” when I watched video of him. I noticed that, despite standing just 5-foot-2 1/2, he was an excellent long-range fighter who possessed extraordinary timing, as well as exceptional two-fisted power. Second, an article written by Boxing.com’s Mike Casey proved persuasive, as respected historians Dan Cuoco and Mike Silver sung Moore’s praises.

“Like his lightweight contemporary Carlos Ortiz, he could do it all – box, punch, in-fight, feint and counterpunch,” said Silver. “Davey methodically broke down an outstanding fighter when he won the title from the formidable Hogan (Kid) Bassey. I think ‘methodical’ is a good word to use in describing Davey’s style but that is not to infer he was ever boring to watch. He was always poised and smooth in his delivery – what we used to call a picture book boxer,” adding that he thought no featherweight in 2012 would last more than three rounds and many would be taken out in one.

“Davey Moore adopted a style to overcome these deficits (of height and reach),” Cuoco stated. “His aggressive counter attack which featured an excellent left jab, ripping body punches and effective pinpoint counterpunching made him one of the most dangerous pound-for-pound fighters competing in the 1950s and early 1960s.”

Davey Moore (right) vs. Olli Mäki

In addition to his back-to-back championship victories against Bassey, Moore, between April 1957 and February 1963, had won 36 of 37 fights, with the only loss coming to unbeaten Venezuelan Carlos Hernandez, who broke Moore’s jaw, scored six knockdowns and forced a corner retirement after round seven. That run of dominance was certainly a factor in my decision.

That streak – and ultimately his life – was ended by future Hall of Famer Ultiminio “Sugar” Ramos in Los Angeles. Moore, who entered the fight a two-to-one favorite, despite experiencing weight-making issues, was only 29 years old when, during a knockdown, the back of his neck struck the bottom rope and caused the brain injury that would kill him 75 hours later. We’ll never know what would have happened had the accident never occurred; we as voters can only go by what happened and how he performed. To me, he performed well enough.

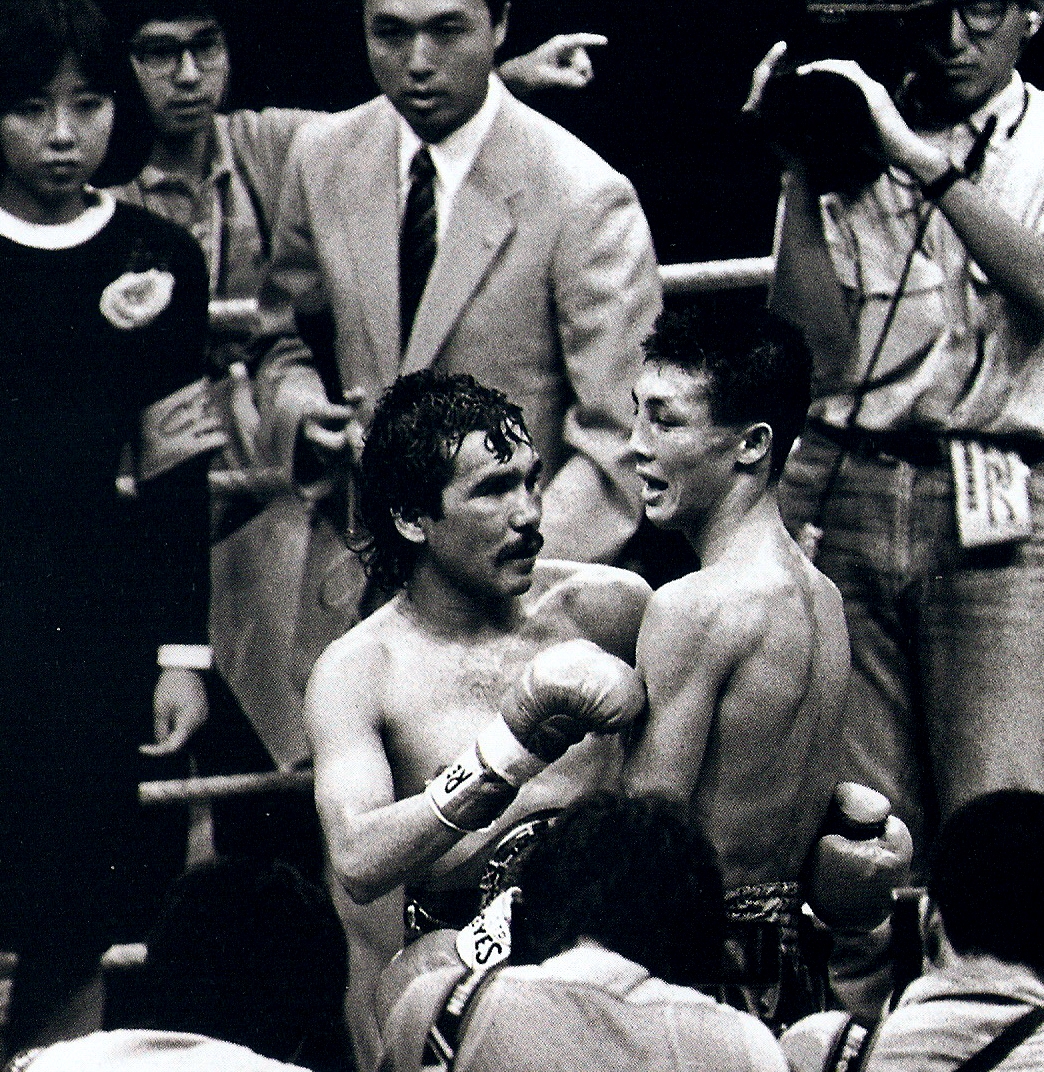

Like two years earlier, I affixed a checkmark beside longtime 115-pound titlist Jiro Watanabe, who was one of the fighters I included among my IBHOF “Deserving Dozen” in a November 2003 article I wrote for MaxBoxing. My reasons then are my reasons now: He, along with Gilberto Roman and Khaosai Galaxy, helped legitimize the 115-pound weight class with a reign that extended nearly four years and 11 defenses, as well as featured successful defenses against Gustavo Ballas (57-1-1 at the time), former flyweight titlist Shoji Oguma, the 33-1-1 Luis Ibanez, future champion Soon-Chun Kwon, the 16-0-1 Celso Chavez and Payao Poontarat twice, the first to unify the WBA and WBC belts. (He stopped Poontarat in the rematch.) He lost his belt to Roman, who would go on to achieve his own greatness. The only minus is that Watanabe never unified with Galaxy, who won the WBA belt stripped from Watanabe because the Japanese opted to unify with Poontarat instead of fulfilling his mandatory with Galaxy.

During this voting cycle, two fighters emerged as sentimental favorites: Tony DeMarco for the Old-Timers and Donald Curry for the Moderns. Although I had not voted for either in past years, the respective campaigns prompted me to revisit their candidacies. Again, at least for me, they fell short and the reasons remained unchanged.

One part of me really wanted to place the checkmark before DeMarco’s name. For one, DeMarco was one of his era’s most exciting fighters and his explosive left hook was one of the sport’s most dangerous weapons. It was dynamite personified. His two brawls with Carmen Basilio were instant classics and the rematch was named The Ring Magazine’s Fight of the Year. As a 21-year-old up-and-comer, DeMarco staged a dramatic come-from-behind rally to defeat the favored Paddy DeMarco by split decision and he stopped reigning lightweight king Wallace “Bud” Smith in a non-title affair. Finally and most compellingly DeMarco is now 86 years old – boxing’s second-oldest living world boxing champion behind the 87-year-old Robert Cohen – and his dream is to be inducted into the IBHOF while he can still fully enjoy the experience. Worse yet, if he fails to make it this year, his portion of the Old-Timers ballot won’t be voted on for another two years.

Tony DeMarco

Based on what I’ve heard from other voters, I believe he will be enshrined. If he is, I’ll be very happy for him and for his family, friends and fans. Other thrill-a-second fighters such as Arturo Gatti, Rocky Graziano and Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini have been enshrined, so there is precedent for DeMarco to be elevated. However in order for him to do so, he’ll have to get across the finish line without my vote. Here’s why:

One of the measures I use in selecting inductees is dominance over ones peers and the best measure of that is how he performs in championship fights. If one includes DeMarco’s two fights for the Massachusetts version of the world welterweight title against Virgil Akins, “The Boston Bomber” went 1-4 in championship fights – and all four defeats were by knockout. Yes, DeMarco showed a fighter’s bravery by choosing to defend his newly-won championship against Basilio just 70 days after winning it from Johnny Saxton. More than that, he did so in Basilio’s backyard of the War Memorial Auditorium in Syracuse. Yes, he twice came within an eyelash of becoming the first man to stop the legendary onion farmer, who, after winning the title from DeMarco, returned the favor by defending against DeMarco before the challenger’s home fans in Boston. Yes, his four fights with Basilio and Akins were incredible slugfests that featured numerous knockdowns and other plot twists. Those fights and others, such as his one-round annihilation of Chico Vejar between the two Basilio bouts and his victories over an aged Kid Gavilan and the 50-3 Vince Martinez, helped him get onto the ballot. For that alone, DeMarco advanced further than 99.999% of the people who ever dared to compete in the professional ranks.

All that said, boxing is a bottom-line business and so is voting for the Hall of Fame. Fairly or unfairly athletes in all sports are judged by their wins and losses in championship competition and, for boxers, that involves how they perform in championship fights. For me, consistent victories on the biggest stages count heavily as a Hall of Fame voter and while it is unquestionably true that DeMarco possessed Hall of Fame-level heart, it also is unquestionably true that he didn’t put together a Hall of Fame-level resume.

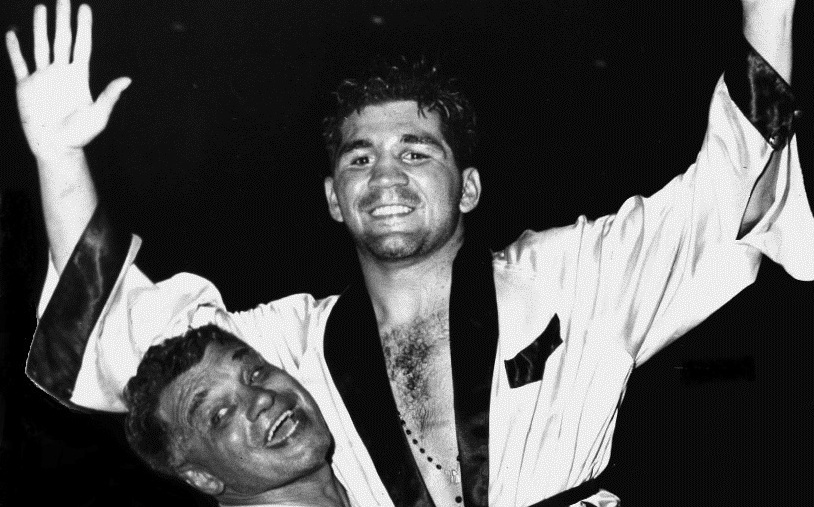

My explanation for my non-vote for Curry should serve as a transition to my deliberations concerning the Modern ballot. So why did I turn down Curry’s candidacy? I can say that “The Lone Star Cobra” was, without doubt, on his way to “shoo-in” status during his run as welterweight champion. Pre-title victories over Bruce Finch, Adolfo Viruet and Marlon Starling were noteworthy and his 147-pound title run featured excellent victories over Jun-Suk Hwang, back-to-back-to-back fights against Starling, the 31-0 Elio Diaz and the 58-1 Nino LaRocca and his smashing title unification blast-out of Milton McCrory.

Had Curry’s career ended at that point, he would have had a good chance of being a first-ballot inductee. As it was, he was poised to make a run toward a belt at 154, then a head-to-head showdown against No. 1 pound-for-pound king – and undisputed middleweight champion – Marvelous Marvin Hagler. Based on how Curry looked at the time, one had every reason to believe he could go all the way and reach his triple championship summit.

It wasn’t to be and because Curry’s fall was so steep – and so unexpected – his candidacy, in my eyes, also fell apart. A weight-weakened Curry was crushed in six rounds by massive underdog Lloyd Honeyghan and, three fights later, he was on the wrong end of a one-punch knockout by WBA junior middleweight titlist Mike McCallum, who Curry was favored to beat. Three fights later, Curry did capture a 154-pound belt by beating longtime titlist Gianfranco Rosi in Italy but, just when it appeared he had righted the ship, he lost the championship in his first defense against unheralded Frenchman Rene Jacquot, the second time Curry was victimized by an earthshaking upset loss. In fact, The Ring Magazine deemed the Honeyghan and Jacquot defeats as its “Upsets of the Year,” a measure of Curry’s high level of respect entering those fights, as well as the shocking nature of his losses. Two more KO defeats in back-to-back title shots against Michael Nunn at 160 and Terry Norris at 154 effectively finished Curry’s run near the top levels of the sport.

Lloyd Honeyghan (right) vs. Donald Curry. BoxRec. Image courtesy of www.BoxRec.com

So while Curry’s star shone brilliantly during his best days, I couldn’t ignore the flipside when assessing his worthiness for enshrinement. That’s why I left his space blank.

If Curry didn’t make the final five, who did? Two of my checks were instantly devoted to Dariusz Michalczewski and Gilberto Roman and here are the reasons I voted for “The Tiger”:

* Michalczewski’s 23 consecutive defenses of the WBO belt are just two behind Joe Louis’ all-time record and his reign of nine years and one month is the longest in light heavyweight annals.

* Nineteen of Michalczewski’s 23 defenses ended inside the distance and his 14-fight title-fight KO streak between October 1997 and March 2003 is second behind Wilfredo Gomez’s all-time record of 17.

* The four title fights that went the distance were won with plenty of points to spare and the most important of those came in a three-belt unification against IBF/WBA king Virgil Hill (118-110, 117-112, 116-113), who was fresh off his own title unification triumph against Henry Maske.

* Michalczewski ran his record to 48-0 but, like others before him, fell short of Rocky Marciano’s magical 49-0 mark, when he lost on points to Julio Cesar Gonzalez. Still, 48-0 is 48-0 and when one wins 25 title fights to reach that rarified air – including winning the WBO cruiserweight title from Nestor Giovannini right after dethroning WBO light heavyweight king Leeonzer Barber, a belt he never defended – that’s pretty special.

* Michalczewski is often compared to title counterpart Roy Jones Jr., who won the WBA and IBF titles after Michalczewski was stripped for not defending against both their mandatories within an absurdly short period of time. They share five common opponents and while Jones beat the man who beat The Tiger, Michalczewski fared rather well against the others – Virgil Hill UD 12 by Michalczewski, KO 4 by Jones), Richard Hall (TKO 11 and TKO 10 by Michalczewski, TKO 11 by Jones); Derrick Harmon (KO 9 by Michalczewski, TKO 10 by Jones) and Montell Griffin (TKO 4 by Michalczewski, L DQ 9 and KO 1 by Jones).

Dariusz Michalczewski (right) vs. Virgil Hill

That said, I believe Michalczewski’s candidacy has suffered for two reasons. First, he, the owner of the line of succession because he was the three-belt champion before Jones was, never faced Jones to unify the titles, and (2) had they met, many believed Jones would have destroyed Michalczewski. Unfortunately we can only speculate what would have happened but that alone shouldn’t negate The Tiger’s considerable accomplishments at the championship level. Those accomplishments are why I’ve placed a check by his name every year he’s been on the ballot and why I will reserve a check for him every year until he’s elected.

As for Roman, I voted for him because:

* He is one of the best 115-pounders who has yet lived and is one of boxing-rich Mexico’s most prolific and successful champions. His 11 defenses over two reigns ties him with Omar Narvaez and Jiro Watanabe and ranks only behind Johnny Tapia’s 13 and Khaosai Galaxy’s 19.

* He won his first belt from the long-reigning Watanabe in Japan and he also won title bouts in France, Argentina, Thailand and the United States.

* Although he was officially 1-1-1 against Santos Laciar, a strong case can be made that he could have won all three had he not been stopped on cuts in their second meeting.

Gilberto Roman (left). Photo courtesy of www.wbcboxing.com

* He defeated Laciar’s conqueror Sugar Baby Rojas twice (both by unanimous decision) and other victims include lanky southpaw Edgar Monserrat, former flyweight champs Antonio Avelar (in fight two) and Frank Cedeno, future 122-pound titlist Kiyoshi Hatanaka and Juan Carazo, who beat Laciar to earn his chance against Roman. He also scored good wins against onetime bantamweight title challenger Paul Ferreri and flyweight contender Antoine Montero.

* Finally Hall of Fame trainer Ignacio “Nacho” Beristain thought so much of his pupil that the “Roman” part of his Romanza Gym is named for him.

For the other three checks, the competition was fierce between nearly a dozen viable names. In times like this, I chafe under the five-checkmark maximum but, until they are changed, the rules are the rules. Here is who made the cut and why:

Ivan Calderon – This is his second year on the ballot and, as was the case last year, he made the cut for the following reasons:

* During his prime, he was considered one of the very best defensive fighters of his time.

* He held a world title almost continuously for more than seven years (the WBO strawweight belt from May 2003 to April 2007 and the WBO junior flyweight strap from August 2007 to August 2010), an especially difficult feat for those campaigning in the extreme low weight classes because such fighters age quicker.

Former RING/WBA/WBO junior flyweight champion Giovani Segura (left) and Ivan Calderon. Photo credit: Joel Colon/PR Best Boxing

* Calderon recorded 11 defenses at 105 and six more at 108, while beating nine men who had held a title at some point of their careers: Eduardo Ray Marquez, Alex Sanchez, Edgar Cardenas, Roberto Leyva, Daniel Reyes, Isaac Bustos, Hugo Cazares (twice), Nelson Dieppa and Rodel Mayol.

* He boasts a record of 11-3-1 (1 KO) against champions, titlists or Hall-of-Famers, the only fighter among the 32 Modern candidates to boast double-digit wins in this category.

* While commentators criticized his constant movement, his lack of power and the sameness of every round, Calderon was the ultimate ring general who banked round after round on the scorecards. One look at his score lines, especially between 2003-’07, illustrates the degree of his strategic command.

* Because Calderon lacked fight-ending power in either hand, he had to depend on his array of skills to build up insurmountable mathematical leads and keep his aggressive opponents at bay. Calderon’s skills were so advanced – and he was so comfortable amid the heat of combat – that he occasionally executed his moves with a showman’s flair; more than once his duck-under moves ignited shouts of “Ole!”

I’ve always had a soft spot for fighters who succeeded without the safety net of one-punch power such as Willie Pep, Miguel Canto, Nicolino Locche and Hilario Zapata and that soft spot – along with everything else described above – moved me to invest the third check.

Wilfredo Vazquez Sr. – Like the other candidates I’ve listed so far, Vazquez is a repeat choice. He was bumped last year because of the shoo-in candidacies of Vitali Klitschko, Erik Morales and Ronald “Winky” Wright, all of whom were enshrined, but now he has made his return to my Top 5. Here’s why:

* While a select number of fighters have won a world title after losing their pro debut, even fewer have gone on to become a titlist in three weight classes. After losing a four-round decision to William Ramos in his debut (and after losing two bouts to then-WBC bantamweight king Miguel Lora and former WBC flyweight champ Antonio Avelar in a three-fight stretch), Vazquez won the WBA bantamweight title, by knockout, in South Korea, over Chan Young Park, whose only loss in his last 19 fights was a 10-round decision to future Hall-of-Famer Khaosai Galaxy.

* Including the Park win, all three of Vazquez’s championships were won as a road underdog by knockout. After losing the 118-pound belt to Khaokor Galaxy by split decision in Thailand, he lost his next fight to Raul “Jibaro” Perez by decisive 10-round decision, then, three fights later, was stopped in one round by Israel Contreras, himself a future beltholder. Who would have ever expected Vazquez to capture his second divisional title just four fights later from his previous conqueror Perez (who had just won his second divisional belt following a dominant reign at bantamweight) in Mexico, with a smashing third round knockout? Then just three months shy of his 36th birthday, Vazquez won his third belt with a come-from-way-behind 11th round TKO over WBA featherweight king Eloy Rojas on neutral turf in Las Vegas. At the time of the KO, Vazquez was down 100-92, 98-92 and 96-94.

Wilfredo Vazquez Sr.

* Not only did he win belts at 122 and 126, he kept them and he beat quality fighters in the process. His 122-pound reign spanned three years and nine defenses and his best wins came against future titlists Thierry Jacob (TKO 8, KO 10), former 122-pound beltholder Luis Mendoza (UD 12), eye-blink 115-pound titlist Juan Polo Perez (UD 12) and future Hall-of-Famer Orlando Canizales (SD 12) in what was considered a surprise, considering Canizales was (and remains) the all-time record-holder at 118 with 16 successful defenses and he was portrayed as the “A-side” fighter on the HBO broadcast. After dethroning Rojas at 126, Vazquez notched defenses against Bernardo Mendoza in California (KO 5), Yuji Watanabe in Japan (KO 5), Roque Cassiani in New York City (UD 12) and Genaro Rios in Las Vegas (UD 12). Vazquez only lost the title due to politics, for, instead of fighting a mandatory against previous conqueror Antonio Cermeno, he opted to meet WBO king Naseem Hamed for considerably more money and prestige. Even four months shy of 38, Vazquez fought “The Prince” credibly before losing by seventh round TKO.

Yes, Vazquez had some shortcomings and stumbles – four of his nine defeats were by KO and he really struggled with tall speedsters – but, in my eyes, his accomplishments and his ability to overcome career adversities and adverse situations far outweigh his negatives. That’s why he made the grade with me in this most difficult year.

So who got the fifth and final check? From a pool of nearly a dozen credible candidates, I chose someone who possessed an excellent skill set as well as a record of long-term success that I couldn’t ignore:

Chris John – “The Dragon” amassed numbers that rank highly in the history-rich featherweight class: 18 successful title defenses (one behind Eusebio Pedroza’s division record 19) and a nearly 10-year reign that trails only those of Johnny Kilbane and Abe Attell, as far as elapsed time. Also John ran his record to 48-0-3 before losing the final fight of his career to Simpiwe Vetyeka and, like Michalczewski, a sizable chunk of those bouts were waged under championship conditions.

Critics will say John’s 12-round unanimous decision over Juan Manuel Marquez – the biggest name on his record – was the result of friendly judging in Indonesia and there’s a case to be made for that. But afterward John proved himself to be a skilled operator capable of beating challengers on the road with his blend of mobility, high work rate, timely punching and ring generalship. He beat Tommy Browne and Stas Merdov in Australia, defeated Zaiki Takemoto and Hiroyuki Enoki in Japan, beat Shoji Kimura and the 43-0 Chonlatarn Piriyapinyo in Singapore and posted what should have been two decisive victories over Rocky Juarez in the U.S. (The first meeting was deemed a draw while the rematch was a victory.) Aside from the Marquez fight, John’s decision victories were achieved with points to spare, another indicator of his command over his opposition.

Chris John (right) vs. Rocky Juarez. Pphoto credit: Ethan Mille

He is one of four Indonesians to capture world honors (Ellyas Pical, Nico Thomas and Muhammad Rachman) and though his record against titlists is just 3-1, the winning percentage of his title defense victims was .858 (502 wins, 66 losses and 17 draws).

This year’s process took place within a 36-hour time period, of which 13 were spent conducting research, as well as writing and editing this two-part article. Although I hated the fact I had to leave out several worthy candidates, I felt good about the final choices I made on all four ballots.

Of course I am not the be-all and end-all in these matters and robust debate lies at the heart of this process. Good and knowledgeable people can credibly disagree about who should and should not be enshrined but at least I am on the record with my choices and have done my best to explain how I voted and why.

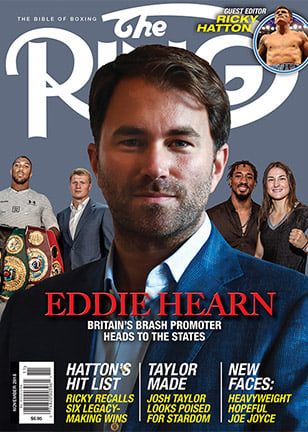

Sometime in December, the IBHOF will announce who will be enshrined next June. Barring ties – which have happened from time to time – the Class of 2019 will include three Moderns, three Non-Participants, two Observers and one Old-Timer. My predictions, which are made with considerable hesitation: Rafael Marquez, Ricky Hatton and Donald Curry in the Moderns; Don Elbaum, Lee Samuels and Guy Jutras in the Non-Participants, Teddy Atlas and Mario Rivera Martino in the Observers and Tony DeMarco in the Old-Timers.

*

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, West Virginia. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 16 writing awards, including two first-place awards, since 2011. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics” (available on Amazon) and the co-author of the newly released book “Muhammad Ali: By the Numbers” (also available on Amazon). To contact Groves about a personalized autographed copy, use the email [email protected] or send him a message via Facebook.

Struggling to locate a copy of The Ring Magazine? Try here or

Subscribe

You can order the current issue, which is on newsstands, or back issues from our subscribe page.