Muhammad Ali-Leon Spinks II: 40 Years Later

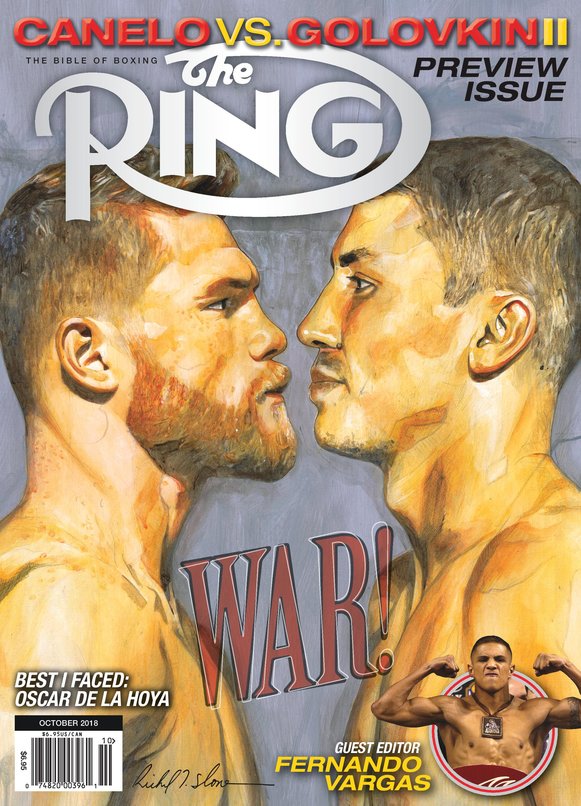

This feature originally appeared in the October 2018 issue of The Ring Magazine.

“In 25 years of sports, I’ve never heard such a crowd,” said ABC’s Howard Cosell. “Never!” It was a Friday night in New Orleans, September 15, 1978, and Muhammad Ali was giving Leon Spinks a lesson in boxing. By the later rounds, as Ali appeared to be dancing away with the victory, Cosell was quoting Bob Dylan’s “Forever Young” and praising Ali for his legendary career. “What an extraordinary man he has been in every way,” Cosell said, his all-too-familiar voice competing with the “deafening din” inside the cavernous Superdome.

The rowdy atmosphere continued when Ali, the winner by unanimous decision, left the ring. “The crowd,” novelist Ishmael Reed observed, “began swaying and moving like a papier-mâché dragon,” while dozens of celebrities, including John Travolta, Sylvester Stallone and Liza Minnelli, followed after Ali as acolytes might a savior. Prior to the bout, Spinks’ trainer, George Benton, had spoken of Ali in almost supernatural terms. “It’s like there is a mystical force guiding his life,” Benton said, “making him not like other men.” Ali, now the first fighter to win the heavyweight title three times, returned to his dressing room and talked about his penchant for shocking the world. “I am from the House of Shock,” he said.

Forty years later, it’s easy to forget that Ali-Spinks II was one of the biggest sports stories of 1978, and how their first bout, won by Spinks and chosen as The Ring’s Fight of the Year, had seemed like the continuation of a longstanding tradition, that of the aging champion losing to a younger challenger, a passing of the torch that usually resulted in the older fighter’s exit from the profession.

Seven months earlier at the Las Vegas Hilton, it had been obvious as early as the first round that something odd was happening. Spinks, a 24-year-old barely out of the Olympics, a young fighter who’d had only seven pro fights and hadn’t looked too good in any of them, was muscling his way through Ali’s high guard and landing uppercuts. Ali tried to box, but Spinks won the round on sheer hustle – what Hunter S. Thompson dubbed his “pure kamikaze style.” At the bell, Spinks patted Ali on the shoulder and walked briskly to his corner, upbeat. This was unheard of. Ali went to his own corner and remained standing, an old-timer’s trick to make the other guy think he wasn’t tired. But Ali had to know that he was in for a long night.

He no longer moved quickly, in the ring or out. He walked casually, like the boss cat in a pride of lions. Since regaining the heavyweight title a few years earlier from George Foreman in Africa, he had grown to hate training, often getting by on nothing but his experience and ring generalship. Yet he was enjoying a kind of fame unmatched by any fighter before or since. From children to the elderly, from citizens of the poorest countries to talk show hosts and world leaders, Ali was adored. There were cynics, of course, who resented Ali as just another greedy, overexposed celebrity. Endorsements for candy bars, bug spray and deodorant, plus appearing as himself in a Hollywood movie of his life, were just the most recent examples of a stardom that had turned increasingly gaudy.

Now the boss cat struggled. With each round, a growing sense of gloom permeated his corner; it was clear to Ali’s handlers that the raggedy-looking challenger was beating their meal ticket. Spinks, an ex-Marine from St. Louis, had a ring style best described as “busy,” all pumping shoulders and head moves, like Joe Frazier without the burning edge. The biggest thing in Spinks’ favor was that he didn’t fear Ali.

“I was very serious during the fight,” Spinks said at the time, “but I also had a lot of fun. He kept saying things to me, trying to make me mad, but all he did was make me laugh. It was like he was telling me jokes. One time he called me a dirty name. I said, ‘Oh, Ali, how could you say such a thing?’ Can you imagine your idol calling you a dirty name?”

Ali tried dirty names and so much more, but Spinks was tireless. Ali rallied in the 10th, knocking Spinks wobbly with combinations, but he couldn’t maintain the attack, not with Spinks hurling himself forward like an unruly dog. After the 15th round, a stormy three minutes chosen by The Ring as Round of the Year, Ali was exhausted and bleeding from the mouth. When the decision was announced – a split in Spinks’ favor – Ali merely walked through the wild celebration in Spinks’ corner, caught the new champion’s attention, and winked. Then he was gone.

Mike Marley, reporting for the Las Vegas Sun at the time, recalls the fight well. “It was a stagnant promotion,” he said. “No one was excited about it. Ali viewed it as drudgery, just another day at the office. A prime Ali would knock Leon out in two rounds. But he wasn’t up for it. He was mentally vacant. He’d been through a very tough fight with Earnie Shavers and he wanted an easy opponent.” Spinks, though, seemed galvanized by the opportunity. “Leon was a little sad at having to beat his hero, but Leon deserved it. I was glad the judges didn’t screw him. The only person who thought Ali won was his brother, Rahman. In the dressing room he told Ali, ‘You were robbed.’ Ali said, ‘Shut up.’”

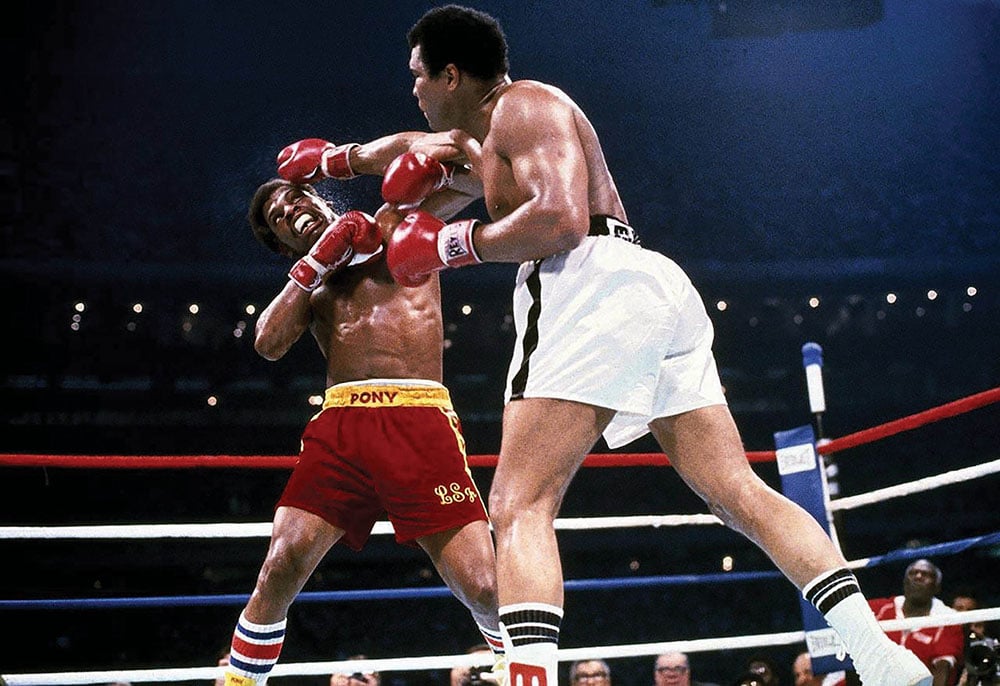

Muhammad Ali was playful at the press conference for his rematch with Leon Spinks, but he was all business during the fight – the last victory of his legendary career.

Muhammad Ali was playful at the press conference for his rematch with Leon Spinks, but he was all business during the fight – the last victory of his legendary career.

Within weeks, Ali announced his plans to regain the championship. “I will drop bombs on Spinks,” he said. “I’m gonna bury him.”

And so, after goodwill trips to Russia and Bangladesh, Ali prepared to meet Spinks again.

Ali was solemn as he trained for the rematch. There was talk of his punishing regimen this time, but no amount of running or calisthenics would bring back the magic. The greatness, the speed, the ability to pull fights out of the fire, had been drained from Ali by fame, by women, by being the most important boxer in the history of the business. He was only 36, but he seemed weary and depleted. As he’d done many times in the past, Ali promised this would be his last fight.

“I’ve been doing it for 25 years, and you can only do so much wear to the body,” Ali said. “It changes a man. It has changed me. I can see it. I can feel it.”

What did he have left? He still had a jab. It was no longer quick, blinding or stinging, but he still had it. He had a right hand. Not the chopping right that had cut and KO’d so many fighters, but it was still useful. His legs were only good for a few rounds, and his reflexes were no longer sharp; all he had was a jab and a right hand, the first punches taught to him by Officer Joe Martin back in Louisville. Would this be enough?

“Greg Page, Tony Tubbs, and Michael Dokes were his sparring partners,” Marley remembered. “Three guys who would become champions. He would just rope-a-dope and let them pound on him. I don’t think that did him any good.” There was also the job Ali did on his own psyche. “He’d mesmerize himself. He’d keep talking about winning the title for the third time. That’s all he would talk about, until we were all sick of hearing it.”

As for Spinks, he may have won the championship, but he didn’t know how to be a champion. One alphabet group had already stripped him, leaving him with only the WBA belt. There were driving mishaps, a cocaine bust, silly behavior; he’d become a national joke, providing fodder for comedians ranging from Richard Pryor to Johnny Carson. During the week of the rematch in New Orleans, he spent his nights in seedy bars getting drunk. “I’m surprised,” promoter Bob Arum said, “he didn’t wind up with a knife in him.”

The rematch was anything but stagnant. It was a kind of pop cultural phenomenon. An estimated audience of 90 million watched the event in some 80 nations. The bout drew a 46.7 rating, meaning nearly half of the televisions in America were tuned in. The attendance was 63,350, which at the time was the largest indoor attendance ever for a boxing match. Most were on their feet from the beginning, chanting, “Ali! Ali!”

Once again the focus of a major event, Ali was buoyed by the vibe, by the sheer hokey spectacle of it all. Looking as somber as a judge, he entered the ring to “When The Saints Go Marching In,” while Spinks came in to “The Marine’s Hymn.” After much ballyhoo, the year’s biggest boxing drama began its second act.

The early rounds were close, each fighter trying to scratch out some territory, but by the sixth, Ali’s confidence was growing. He jabbed and circled, threw enough rights to keep Spinks off-balance and controlled the action. If Spinks lunged forward, Ali merely grabbed him and held on. It was, as Pat Putnam of Sports Illustrated described, “a demonstration by an old master educating an inexperienced youngster in the fine points of the craft.”

It helped that pandemonium reigned in Spinks’ corner. Benton departed after a few rounds, angry that Spinks’ other handlers were shouting him down. Spinks fought hard, but he looked unhappy. Ali’s trainer, Angelo Dundee, teased Spinks without letup. At one point, Dundee shouted, “Goodbye, Leon!”

The fight played out in a series of mini-skirmishes, which Ali would get the best of before wrestling Spinks into the ropes. It wasn’t a beautiful display of boxing, but it worked. Most surprising was Ali’s movement; the old legend could still float like a butterfly. At various times, Ali stopped mid-ring to do a quick shuffle, bringing the customers to a roar that shook the ceiling of the Superdome. This was Ali, risen from the ashes to stick and move across the universe. The scorecards – 10-4-1, 10-4-1 and 11-4 – were almost unnecessary.

Beating Spinks wasn’t on par with his most dramatic victories, but it was an important part of the Ali saga. And like all sequels, Ali-Spinks II wasn’t quite as exciting as the original. However, like a sequel can sometimes be, the rematch was fun. It had a character we liked, and an ending that, though predictable, was satisfying. Order was restored; the king was back on his throne.

Spinks fought on for many more years, but his upset win over Ali would remain the highlight of his career. “Ali is still my idol,” he said after losing the rematch.

Much has been forgotten since then, such as actress and Playboy model Edy Williams doing a striptease during the undercard; the accusation by Ali’s camp that Spinks had been energized in the first bout by the contents of a mysterious brown bottle; Joe Frazier singing the national anthem in New Orleans; the intense row among promoters and investors after the rematch, with Ali claiming his payday was short by a million dollars; and how 1978 marked a turning point in heavyweight history, with WBC president Jose Sulaiman stripping Spinks for not fighting Ken Norton, which led to Larry Holmes winning that organization’s belt, forever splintering what had once been the most cherished title in sports.

As for Ali, he had two more fights, lost both, and then went on to a life of health problems. If he’d stopped in 1978, maybe things would’ve been different. Of course, he probably felt invincible after winning the Battle of New Orleans. But in his quiet moments away from the crowds and the cameras, he knew nature always takes the last round.

He could see it. He could feel it.

Struggling to locate a copy of The Ring Magazine? Try here or

Subscribe

You can order the current issue, which is on newsstands, or back issues from our subscribe page.