Samuel Vargas knows he’s always one punch away from upsetting Amir Khan

TORONTO – There’s a little more than a month to go before Samuel Vargas steps into a ring with Amir Khan, in Birmingham, England, but the seeds for this match-up had already been planted three years ago.

In 2015, Khan had stopped in Toronto for a few days, on his first trip to the city. Lee Baxter, a local tattoo shop and night club owner-turned-boxing promoter, had been asked by a friend to look after the former unified junior welterweight titlist. Walking inside a night club, Baxter introduces Khan to Vargas, then an unknown fighter with a 20-1-1 record.

“I said, ‘Yeah, he’s a welterweight as well. (Khan) goes, ‘There’s no way; he’s too big. He must be a super welter,’” remembers Baxter.

“I said, ‘Yeah, he’s got a pretty good record. I think you guys will fight one day.’ And he said, ‘You think?’ I said, ‘No, I know.’

That conversation near the front of a night club was forgotten about until late-June, when Vargas and team walked into the Arena Birmingham, in the United Kingdom, to meet reporters where they’ll meet at center-ring on September 8.

“I think what really happened is, (Khan) didn’t even put two-and-two together, when he approved Vargas, until we got to the press conference, and then he goes, ‘Oh shit; it’s you guys.’”

Much has changed since those prophetic words were spoken. Vargas, 29, has had two shots at the upper-crust of the division, against Errol Spence Jr. in 2015 and Danny Garcia in 2016, losing by stoppages in both. Against Garcia, Vargas said he was bleeding from one of his ears when the corner and referee intervened simultaneously in the seventh.

“They taught me the biggest lessons in my career,” said Vargas, who has gone 4-0-1 since the Garcia fight.

“When you get up there, it’s a whole different ball game, and it’s gonna happen. Everything happens quick; it’s all up in your face. A lot of times, you think you’re mentally ready for that moment but you’re really not.”

Khan, 31, has had it rough of late, as well. In May of 2016, he made a surprising choice to move up to middleweight, and did well until he wasn’t doing well at all, getting knocked out cold with one right hand from the much larger Canelo Alvarez. He was inactive for nearly two years before returning last April, stopping another Toronto resident Phil Lo Greco in just 39 seconds.

“I don’t call that a comeback. It was a show really; it wasn’t really a fight,” said Vargas. “If he’s expecting the same 40 seconds, it’s a different fight right now.”

For Khan (32-4, 20 knockouts), Vargas represents another hurdle to clear before he re-enters the big fight realm. For Vargas (29-3-2, 14 KOs), the fight represents something much more significant.

“For me this is all or nothing. I either win this or wither,” said Vargas, a father to an eight-year-old son.

The Hardknocks Boxing Club in downtown Toronto has become a hub for activity for the growing Ontario fight scene. The single-ring gym is owned by Baxter, who first met Vargas when he came into Baxter’s shop to get a tattoo. The two became close friends, with Baxter going from sponsor to manager before eventually becoming Vargas’ promoter.

“I’d never even been to a boxing fight,” said Baxter of when he first met Vargas. “When I checked it out, I saw that there was a big void in the industry. Like how were a lot more people not knowing about this?”

Baxter has been a very active promoter since 2015, and says he’s in year two of a five-year plan to make Toronto one of North America’s biggest boxing towns. Among the bigger shows of which he’s been part are the Adonis Stevenson-Badou Jack light heavyweight title fight in May, and the upcoming co-promotion with Evander Holyfield for the Jose Sulaiman Cup semifinals on August 25.

Seated on the ring apron unpacking his lunch is Chris Johnson, once among the most decorated amateur boxers in Canada’s history, having earned a bronze at the 1992 Olympics and 1991 World Championships, as a middleweight, to go along with the gold he won at the 1990 Commonwealth Games and silver at the 1991 Pan American Games.

He was a good pro too, training with Bill “Pops” Miller (who also trained James Toney) and facing Antwun Echols, Herol Graham, Reggie Johnson and Antonio Tarver before trading in his gloves for punch mitts. Among those he coached were Steve Molitor, whom he led to two tours with the IBF junior featherweight title.

Johnson was the first trainer to put gloves on Vargas when he was 16. Vargas, who came to Toronto from his native Colombia at age 14, found himself in the streets getting in trouble. His mother sent him to Johnson’s gym in nearby Mississauga, and the sport finally gave him a place where he felt he belonged in his new country.

“I always thought Sammy was special because of his work ethic and his heart. He’s one of those kids who had no quit in him,” said Johnson of his first impressions of the young Vargas. “You can build skill – I’m a skill builder – but there’s certain things you can’t build. You can build power to an extent, but you can’t build heart.”

Johnson guided Vargas through a brief 10-fight amateur dalliance, assessing early on that he didn’t have the sort of hand and foot speed to succeed at the international level of the unpaid ranks. He figured Vargas, whom he nicknamed “The Bull, ” would be better served in longer fights in which his pressure can wear out opponents.

“I wouldn’t expect him to go to the Olympics,” said Johnson.

Vargas never cared much school, found it to be “robotic.” He had entertained the thought of joining the Army but wasn’t yet a citizen of Canada. Instead he turned pro in 2010, and went unbeaten in their first 13 pro fights before splitting. Vargas had been training with Philadelphia’s Billy Briscoe in recent years, having his hand raised most of the time, when fighting at home, but falling short in his two shots at the top level in the United States, and a decision to Pablo Munguia in Mexico back in 2013.

When the Khan fight was made, Briscoe suddenly found himself with a full roster of fighters in Philly. Instead of taking the trip across the border, Vargas made arrangements to resume work with the trainer who knows him better than anyone else.

“We have a connection that’s always been there,” said Vargas.

Camp started last Monday, and Johnson will only have about seven or eight weeks to work. His work will primarily be on focusing on tactics, and making small adjustments from what he observes. And above all, Johnson stresses the importance of leaving the setbacks of yesterday behind, and focusing on the fight in front of them.

“Bumping his confidence,” said Johnson of one area of focus he’ll be working on. “He’s got to know that he’s a lot better fighter than he is, and just putting that into his head and letting him know that he’s at the level that he’s supposed to be at. It’s no luck; it’s his God-given talent, and God-given right to be there.”

It isn’t long into analyzing the challenge Khan brings to a fighter when the focus turns to the matter of his punch resistance. Khan has been on the wrong end of three bad knockouts in his career, and had been on the floor by several other fighters. Every fighter has a puncher’s chance against the Olympic silver medalist from Bolton, England, and the combination of his vulnerability and star power makes this a unique opportunity.

Johnson boils Vargas’ mission to one simple task.

“We’ve got to punch him right in the fucking mouth,” said Johnson. “We have to go out, and in the first two, three rounds, we have to hit him as hard as we can. When we hit him as hard as we can, we’ll know right then and there what Khan has.

“He got knocked out real bad in his second-to-last fight with Canelo, and those type of knockouts, at this point in your career, are usually career-ending knockouts. Perhaps it was destiny for Sam to come at this time because I think it’s gonna be Sam’s time to shine.”

Vargas knows the “glass chin” is an attractive target, and that, though Khan has speed he’s not likely to have seen before, he isn’t facing a puncher as big as Garcia or Spence were.

“Genetically we’re not supposed to receive that much punishment and get back up. Your body can only take so much. Maybe this is the fight for him. He’s older, he’s received a lot of punishment and mileage on him. I just have to go out there and expose him,” said Vargas.

Vargas got a taste of the partisan support Khan would enjoy in Birmingham at the press conference but he also heard from the locals who were rooting for Vargas to win – or rather for Khan to lose. And should Vargas win, he’d validate himself as more than just a local favorite who falls short on the world stage.

When asked what happens if he does as Johnson implores him to and connects with Khan’s chin, Vargas pauses before letting out a smile from behind his sunglasses.

“He goes down. His feet are gonna go all over the place, and I’m gonna hit him again, hit him again, hit him again,” said Vargas, as if that scenario was playing on the insides of his shades.

“If I touch him, he’s going down. That’s a guarantee; left or right, you choose. It’s there; everyone knows it’s there. I just got to land one.”

Ryan Songalia is a member of the Boxing Writers Association of America and can be reached at [email protected].

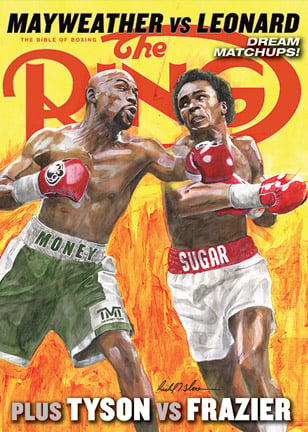

Struggling to locate a copy of THE RING Magazine? Try here or

Subscribe

You can order the current issue, which is on newsstands, or back issues from our subscribe page.