Muhammad Ali: People’s Champ

The memories are personal. They continue to gather in a deep and endless collection of moments in an elevator, or on the street, or at a ballgame. Muhammad Ali’s legacy is in how people recall that single moment when he whispered in their ear, or threw a playful jab in their face.

Ali was a People’s Champ, for sure. But he was more, oh-so-much more. In death, he has been resurrected. The world’s collective memory of him is inexhaustible and sometimes imaginative. It’s also hard to explain.

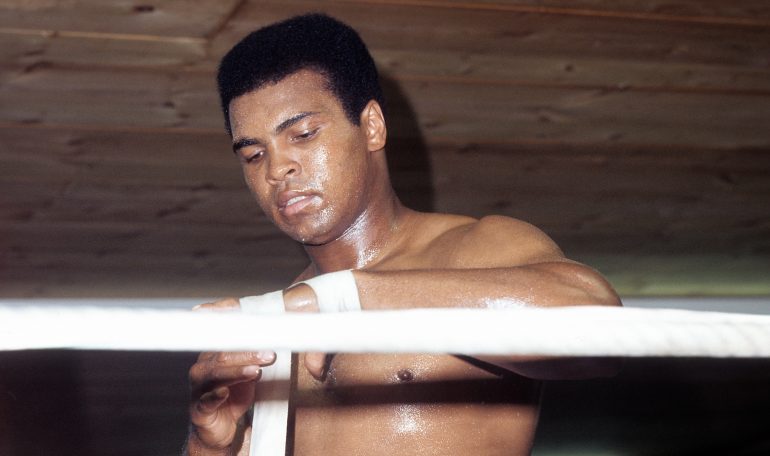

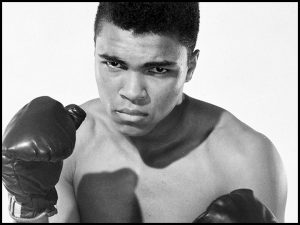

There’s the young man who rumbled and the old one trapped within Parkinson’s’ terrible silence and everything in between. It’s as if his face is a collage of what people see – or hope to see – in themselves.

In the days since Ali died, age 74, at 9:10 p.m. Pacific Time on June 3 at a hospital in Scottsdale, Arizona, he has been called transformational, fearless, humane, controversial, a visionary, cruel, scary, a puncher and a poet Larry Merchant, who was at ringside as a sportswriter for defining Ali fights in New York, Zaire and Manila. “An improvisational genius, kind of a Mark Twain with boxing gloves on.”

There’s something for everyone in who he was, who he became and who he still is. Ali did what nobody would have ever predicted when he was at his polarizing best as a heavyweight champion with as many opinions as punches during the divided 1960s. He became a unifying force.

How that happened is the overriding theme to what Merchant calls his uniquely American character. Ali always changed and – more important perhaps – was never afraid to.

He embraced change in himself and was transformational because the people he challenged and fought on both sides of the ropes eventually changed too.

There’s no better example than George Foreman. Foreman was the Mike Tyson of his time before he faced Ali in the 1974 Rumble in the Jungle in Zaire. Foreman was feared, an angry man who used to bully people on the streets of Houston’s Fifth Ward.

“I really was a monster,” Foreman said.

Few gave Ali any chance at beating Foreman. If anything, there was fear for what might happen to Ali in the face of Foreman’s lethal power, which bounced Joe Frazier off the canvas like a soccer ball with six knockdowns within two rounds in a 1973 title fight in Kingston, Jamaica.

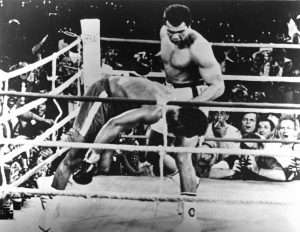

Yet on Oct. 30, 1974, Ali surprised his corner with the rope-a-dope, a tactic then and an enduring metaphor now. Ali endured punishment from one of the biggest power punchers in history.

Ali (right) finishes off Foreman in Zaire. Photo by THE RING

It was a risk and perhaps a reason for the Parkinson’s that would show up a decade later. But the fearless Ali did it anyway, exhausting and taunting Foreman before knocking him out in the eighth round to win the second title in his three lineal championships.

The loss, Foreman’s first, shattered his confidence. He had lost his title. Lost his identity. Foreman returned to the ring in 1976 and fought six times, losing the sixth bout to Jimmy Young. That’s when he quit. He preached on street corners and wondered what had happened to him on that night, Halloween’s eve, in Zaire.

Foreman finally figured out Ali had changed him. For the better.

“Just my association with him transformed me,” Foreman said.

In 1987, Foreman resumed his career. Physically, he was slower, but his personality was more agile than it had ever been when he was an angry young man. The sullen heavyweight of the 1970s was reborn as a celebrity with quips about cheeseburgers. He had become a hugely successful businessman with a grill to sell. And he had an ambition to become the oldest heavyweight champ in history. On Nov. 5, 1994, in Las Vegas, Foreman, then 45, achieved the boxing goal, scoring a 10th-round stoppage of Michael Moorer at the MGM Grand.

None of it would have happened, Foreman said, without Ali.

‘’We were like one guy,’’ Foreman said on the morning after Ali’s death. ‘’But this morning I realized that the greatest piece of us all was Muhammad Ali.’’

In Ali, Foreman experienced what so many seem to have found in the legendary fighter, who bragged about being The Greatest, yet also displayed a common touch and reassuring charisma.

Within the rap-like lyrics that included the promise of how and when he’d knock out Frazier or Foreman or whomever else was next, there was never the fear of losing.

Like anybody else, Ali didn’t seek defeat. But there was always the sense that he understood its inevitability. Ali was prepared for it, first in the ring and then over the final 32 years of his life battling Parkinson’s.

It can be argued that the substance to his claim on being The Greatest rests in how he responded to defeat. In this era of the wealth gap, the one percent has insulated itself from loss in much the same way that the unbeatenF loyd Mayweather Jr. Protects his “0” and claim on being TBE – The Best Ever. Instead of challenging Gennady Golovkin, Mayweather talks about a circus charade against mixed martial arts star Conor McGregor.

Without defeat, Ali would never have confronted the truest test of character. It rests in dealing with loss, coming back from it, especially in a sport so defined by adversity.

Ali won his third lineal title on Sept. 15, 1978, a unanimous decision over Leon Spinks in a rematch of his split-decision loss to Spinks seven months earlier.

He beat Foreman for the title in his 15th fight since losing to Frazier in 1971’s so-called Fight of the Century at New York’s Madison Square Garden. The 15-fight run included a 1974 victory by unanimous decision over Frazier and a 1973 rematch in which he scored a split decision over Ken Norton, who beat him and broke his jaw in their first one. He called himself The Greatest, and he proved it – again and again – by coming back.

His toughest loss, perhaps, came about as the result of a three-year, four-month suspension – June 28, 1967 to Oct. 26, 1970 – for refusing to be drafted into the Army. He opposed the Vietnam War.

“I ain’t got no quarrel with the Viet Cong,” he said then, famously or infamously, depending on the perspective.

Here’s a personal story, my Ali moment: A couple of years before Ali said no to the draft and was subsequently convicted in a case overturned by the Supreme Court, I was a kid, an Army brat, living in base housing at Schofield Barracks in Hawaii.

It’s where I first got interested in boxing. In my early and mid-teens, I’d wander over to the barracks and watch battalion smokers. It was also where and when I first heard about Ali. He had beaten Sonny Liston in 1964 for his first title and then changed his name from Cassius Clay to his Muslim name.

Then I started seeing the famous Neil Leifer photo of Ali standing over a fallen Liston, celebrating a victory in their May 1965 rematch, on the walls of young African- American troops who lived in the barracks. That December, those same troops, all part of the 25th Infantry Division, began to deploy to Vietnam. Within weeks, I began to see some return in body bags.

When Ali refused to be drafted, I thought of those body bags. I was offended, angry. But not as angry as my father, a career soldier who had fought his way across Europe in World War II.

My dad and I used to watch the Friday night fights on a black-and-white television. He was a Joe Louis fan. He was part of the generation that could tell you exactly where they were when they heard about Louis’ first-round stoppage of Max Schmeling in their 1938 rematch. He admired Louis as a fighter and for his military service. What Ali did enraged him. Then, in 1968, he went to Vietnam.

Thirteen months later, he came back a changed man. He didn’t talk much about Vietnam, if at all. He didn’t talk about Ali, either. In my conversations with him, I never mentioned Ali, although by then I had come to admire him for his stand even though I was still uncomfortable with the memory of the body bags.

My dad is gone now. But I think of him, especially now in the wake of Ali’s death. I don’t think my dad could ever have been an Ali fan. But I have a hunch he would have developed a grudging admiration for him.

Ali didn’t serve but he paid a real price in giving up his prime years and the money that would have been there for him. His hitch would have been two years in a unit that would have used his charisma and celebrity in a mission to boost morale. He would not have had to fight the Viet Cong.

Photo by THE RING

My dad, like Ali, knew hypocrisy when he saw it. Ali’s opposition to that war was his way of saying that American wealth and blood, much of it African-American, was being wasted in a civil war in Southeast Asia while an American war over civil rights was still underway in Birmingham and Selma. It wasn’t that Ali didn’t want to serve his country. He just wanted to serve in the right place. And right time. He did.

In the end, my dad probably would have been a lot like Foreman. Ali would have changed his mind. Arizona Senator John McCain is another example. McCain is also a former military man, an ex-Navy pilot and American hero who spent 5½ years as a prisoner of war after his fighter jet was shot down over Hanoi on Oct. 26, 1967, nearly four months after Ali refused to be drafted.

McCain, a former amateur boxer at the Naval Academy, would go on to write federal legislation in an attempt to reform boxing’s business practices. McCain named it the Muhammad Ali Boxing Reform Act.

“He was a friend and a longtime hero of mine for his trademark dedication and fearlessness, both in and out of the ring,” McCain said.

The fearlessness was always there, before Parkinson’s and throughout the long fight against the disease. Over the last three decades of his life, Ali moved away from some of the controversial causes that defined him as a fighter.

Throughout many of the eulogies and memories of Ali, there’s a repeated mention of a cruel streak. A fighter without one isn’t much of fighter. But that cruelty was expressed mostly in how Ali treated Frazier, a proud African-American and a sharecropper’s son whom Ali managed to turn into an Uncle Tom.

Before Ali won their punishing rubber match in Manila in 1975, he used rhetoric that wounded Frazier in a way Frazier would never forget. In the pre-fight hype, Ali said the bout would be a “killa and a thrilla and a chilla when I get that gorilla in Manila.” Ali also came to regret the insults, telling the New York Times in 2001 that he was sorry for the slurs.

“I said a lot of things in the heat of the moment that I shouldn’t have,” he said. “I apologize for that. I’m sorry.”

Frazier resented Ali for many years, including 1996 when he mocked Ali’s shaking hands before the stirring moment when he lit the torch at opening ceremonies for the Atlanta Olympics.

But old enemies often become old comrades and it looked as if that’s where the Ali-Frazier relationship was headed before Frazier’s death from liver cancer on Nov. 7, 2011. Ali attended Frazier’s funeral.

“I will always remember Joe with respect and admiration,” Ali said then.

In some ways perhaps, Frazier taught him the first real hard lesson about dealing with defeat. Ali was never afraid to confront adversity throughout a life that, first and foremost, told everybody that it’s OK to lose as long as you always come back.

Ali has always come back, thanks to all the moments – big and small – remembered by so many.

“Even if boxing disappears from this planet, Muhammad Ali will be remembered, loud and clear,” Foreman said.

Rest in peace, Champ.