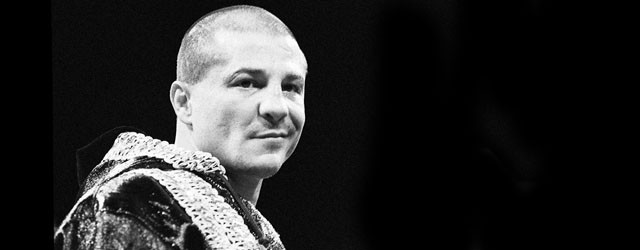

Hall of Fame Class of 2017: Johnny Tapia

A BEAUTIFUL FIGHTER

“I’d soak up all the love of the crowd, my arms raised in the ring, and then I’d go home and crash deep into darkness, a darkness I can barely describe. Pain and emptiness and depression. And that’s when the call of the addiction would come right back on me.”

– from “Mi Vida Loca, The Crazy Life of Johnny Tapia”

When it comes to the bittersweet, few things can match a posthumous induction at the International Boxing Hall of Fame. We wish Arturo Gatti could’ve been there for his induction. He would’ve had fun teasing the critics who didn’t think he belonged there. And Hector Camacho would’ve had a great time; he’d have chosen something special to wear, maybe a gladiator’s helmet.

Continuing in this vein, the fighter we’d most like to see on the podium is the late, great Johnny Tapia. He’ll be enshrined this June as part of the 2017 class. Tapia would be modest. He’d be gracious. He’d be moved, because Johnny Tapia loved boxing as few others do.

We can easily imagine him taking part in the Sunday morning motorcade. He’d sit humbly with his wife and his three sons, waving to the crowd of well-wishers lined up along the sidewalk. He’d have a funny look on his face, as if to say, “I’m just a little guy from Albuquerque. What’s all the fuss about?” But he’d love seeing the other fighters, and he’d say it was an honor to be in their presence. He’d love seeing Marco Antonio Barrera, also part of the 2017 class. They fought each other on HBO in 2002, Barrera winning on points. It was Tapia’s last high-profile fight and his biggest payday. Tapia wasn’t expected to win, but he made Barrera work for the entire 12 rounds. His gallant performance inspired George Foreman to say from his commentator’s perch, “If I got 10 dollars, my last 10 dollars, to spend on a boxing match, the last boxing match I see before I’m called up yonder, I’ll spend it on Johnny Tapia.”

We wish we could interview Tapia one more time. He hid nothing. He talked candidly about everything in his life, going back to when he was a little boy and witnessing his mother, Virginia, being tied to the back of a truck and taken to her murder. He’d tell you all about that nightmare and how he never really woke up from it. That he compiled a ring record of 59-5-2 (30 knockouts) and won five titles (and was 17-1-1 with a title on the line) becomes doubly impressive when you realize he spent his entire career suffering from drug addiction and a bottomless pit of depression.

With one last interview, what would we ask? We’d ask him about the fights. We’d ask about the one with Danny Romero, which was one of the hottest tickets of 1997. Tapia was awesome that night, boxing and clowning and sticking his jab in Romero’s face, winning on points against a younger, quicker guy. Tapia was what the old-timers would’ve called “a beautiful fighter.” Along with knowing every trick in the manual, including the dirty ones, he had a classy style; he used smart footwork, lots of head feints, an excellent command of the basics, a strong jab, a sneaky right hand, and a left hook to the body that could shake the walls of the arena. You could picture Tapia going 20 rounds with Abe Attell or Pancho Villa, the great little men of a century ago, or you could imagine him now, toe-to-toe with “Chocolatito” Gonzales. Tapia would’ve held his own in any era.

With one last interview, what would we ask? We’d ask him about the fights. We’d ask about the one with Danny Romero, which was one of the hottest tickets of 1997. Tapia was awesome that night, boxing and clowning and sticking his jab in Romero’s face, winning on points against a younger, quicker guy. Tapia was what the old-timers would’ve called “a beautiful fighter.” Along with knowing every trick in the manual, including the dirty ones, he had a classy style; he used smart footwork, lots of head feints, an excellent command of the basics, a strong jab, a sneaky right hand, and a left hook to the body that could shake the walls of the arena. You could picture Tapia going 20 rounds with Abe Attell or Pancho Villa, the great little men of a century ago, or you could imagine him now, toe-to-toe with “Chocolatito” Gonzales. Tapia would’ve held his own in any era.

Even in his later years, when he was pudgy and covered with enough tattoos to make him look like an old-time carnival attraction, Tapia was still something beautiful to watch. Nearly a decade after fighting Barrera, he earned a decision over Mauricio Pastrana, who wasn’t an easy night for anybody. A year later, Tapia would be dead at 45, his heart giving out like an engine with too many hard miles on it.

Will we ever stop missing Johnny Tapia? Probably not.

He’d started out like a flash fire, going undefeated in his first 22 pro bouts. A failed a drug test in 1990 sent him into a sort of self-imposed exile that lasted more than three years. Suspended from boxing, he made money by taking on all comers in a local bar for $300 dollars a night and a pack of beer. We’d love to interview him about those lost years and ask about those bar brawls. There’s so much we want to know. And though we wish we could focus solely on the fights, we always return to Virginia Tapia Gallegos and how her death impacted her son’s life.

For instance, was it his mother’s death that cleared the path for Tapia’s boxing career? He hadn’t appeared to be a fighter in the making; he was a self-confessed mama’s boy, slightly spoiled. When Virginia was murdered, Tapia was essentially an orphan – his father, though he resurfaced much later in Tapia’s life, was thought to be dead – so he was raised by his maternal grandparents. Tapia’s grandfather Miguel had been a boxer and was soon teaching Tapia to keep his hands up and his chin down. Tapia’s older cousins would force him into fighting bigger kids in the street and bet on the outcome. Tapia would later say, “I was raised as a pit bull.”

It’s hard to imagine Tapia’s mother letting her precious boy fight in the street like a dog. We’d love to ask him, “Hey, Johnny, what if your mother wouldn’t let you box? Would you have done it anyway?” Granted, with a grandfather who boxed, Tapia would’ve eventually discovered the manly art. But would it become his life’s blood? Would he put so much of his soul into it? His mother’s murder was obviously at the root of his personal problems, but was it also the key to his boxing career?

“Four times they wanted to pull life support. And many more times I came close to dying. But I have lived and had it all. I have been wealthy and lost it all. I have been famous and infamous. Five times I was world champion. You tell me. Am I lucky or unlucky?”

– Johnny Tapia

Examine a fighter’s past and you’ll almost always find some kind of sadness. Tapia’s wife, Teresa, made a telling comment in an interview with BoxingBar.com a year after her husband’s death.

“He would tell me that he believed all fighters are passionate about (boxing) and they fight with all their heart because they’re missing something.” She added, “Johnny felt that boxing was like a little clique that none of us could understand.”

If boxing is, as Tapia suggested, an island of misfit toys, he served for a while as its king.

“When he was in training camp, he was as clean as can be,” said Freddie Roach, one of many trainers to work with Tapia. “I never saw him give in to any temptations, though I know he had his demons and they got the best of him. But he was a great fighter, without a doubt. When I had a chance to work with Johnny, I jumped at it because I knew he was a hard worker, and I love hard workers.”

Champion of the world? Tapia wanted to be the champion of heaven and hell, and all things in between. He was undefeated in 48 bouts when he defended his WBA bantamweight belt against Paulie Ayala. The contest was chosen as THE RING’s 1999 Fight of the Year, but Tapia lost on points. A rematch with Ayala appeared to go Tapia’s way, but the judges again scored in favor of Ayala.

“He took those losses hard,” Roach told THE RING. “They were close fights, but Johnny thought he’d won. He loved to win. The word ‘loss’ wasn’t in his vocabulary. Sometimes his personal life got more attention than what he did in boxing, which is unfair; I had him for seven or eight fights, and I know how dedicated he was to boxing.”

“He took those losses hard,” Roach told THE RING. “They were close fights, but Johnny thought he’d won. He loved to win. The word ‘loss’ wasn’t in his vocabulary. Sometimes his personal life got more attention than what he did in boxing, which is unfair; I had him for seven or eight fights, and I know how dedicated he was to boxing.”

Tapia was also a great community man. He often made himself available to kids, warning them to avoid the mistakes he’d made. Prior to a bout with Jorge Eliecer Julio, he joined forces with the Albuquerque Metro Crime Stoppers to help create a “Guns for Tickets” program. Tapia won the WBO bantamweight title that night, but seemed just as pleased that 57 guns had been turned in. On another occasion, Tapia saw an old man being mugged; he ran in to help, slugging the robbers until they saw stars.

But even at the best of times, Tapia’s “vida” remained “loca.” There were ongoing drug problems, overdoses, encounters with the police, suicide attempts, prison time and mental breakdowns. Doctors declared Tapia dead on five occasions. Yet no one ever recalls Tapia being mean or hostile. His interior battles were his own; he kept them separate from the boxing world that he adored.

“He was great,” said Roach. “I had a lot of fun with him. My favorite Johnny Tapia story was when I was talking to him between rounds of a fight. I can’t recall the opponent, but Johnny was getting away from the game plan. He wasn’t listening to me, so I slapped him in the face to get his attention. Then he listened to me, and won the fight. When it was over, I went to shake his hand. He wouldn’t do it. I said, ‘What’s wrong? You won’t shake my hand?’ Then he slapped me. He said, ‘Now we’re even.’ He was a real character.”

Near the end of his life, Tapia was working with young fighters. He seemed happy. Had he finally knocked the demons back? We’ll never be certain.

As for Tapia’s legacy, he was one of the great fighters of the 1990s. He was Albuquerque’s hero. Out of the ring? Read “Mi Vida Loca, The Crazy Life of Johnny Tapia.” It’s as good a memoir as you’ll ever read from a fighter.

“Four times they wanted to pull life support,” Tapia wrote of his many brushes with death. “And many more times I came close to dying. But I have lived and had it all. I have been wealthy and lost it all. I have been famous and infamous. Five times I was world champion. You tell me. Am I lucky or unlucky?”

He’d probably say something similar in Canastota, New York, this June. We wish he could be there. We can almost hear his acceptance speech. He’d say something about his mother; he’d thank Teresa for her patience; he’d praise boxing.

We’d love to have a word with him when it was over. We’d ask, “Hey Johnny, what was your greatest night in the ring? What does all this mean to you?”

Then again, maybe we’d just back off and leave him alone, let him be with his family. Maybe we’d just congratulate him. We’d say, “You deserve to be inducted.” And we’d say thanks for the memories, Johnny.

You were a beautiful fighter.

RELATED CONTENT ON RINGTV.COM

READ: Class of 2017: Evander Holyfield

READ: Class of 2017: Jimmy Lennon Sr.

READ: Class of 2017: Marco Antonio Barrera

READ: Class of 2017: Eddie Booker

Enjoy this article from THE RING Magazine?

You can subscribe to the print and digital editions of THE RING Magazine by clicking the cover or here. You can also order the current issue, which is on newsstands, or back issues from our subscribe page. On the cover this month: Vasyl “Hi-Tech” Lomachenko.

Struggling to locate a copy of THE RING Magazine? Try here.