The Jewish Golden Age

One of boxing’s more entertaining legends concerns an unsavory manager who brought a Latin American fighter named Marcos to New York in the 1960s, changed his name to Marcus and began touting him in ring circles as “The Star of Zion.” The Star, it was widely advertised, was of Orthodox Jewish vintage, fought to bring honor to the Jewish people and would someday be a superb champion. He blew his cover at a B’nai B’rith luncheon when, hungrily eyeing the matzoh, he said politely, “Please pass the tortillas.”

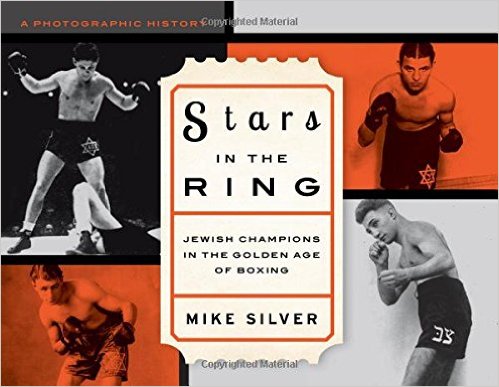

“Stars in the Ring” by Mike Silver (Lyons Press) recalls an era when Jewish fighters were many in number and there was no need for subterfuge of that kind. The book’s focus is on the period from 1900 to 1940, which Silver calls The Golden Age of Boxing and also a Golden Age for Jewish fighters.

“Stars in the Ring” by Mike Silver (Lyons Press) recalls an era when Jewish fighters were many in number and there was no need for subterfuge of that kind. The book’s focus is on the period from 1900 to 1940, which Silver calls The Golden Age of Boxing and also a Golden Age for Jewish fighters.

Silver estimates that there were more than 3,000 Jewish boxers in the United States during those four decades. That was between 7 and 10 percent of the total number of professional boxers plying their trade at that time, he writes. During the same period, there were 29 Jewish world champions. In the 1920s, 14 of boxing’s 66 world champions were Jewish. Putting these numbers in further perspective, only 52 Jews played major league baseball from 1900 to 1940.

“An unprecedented confluence of social and historic events,” Silver writes, “converged to create one of the most unique and colorful chapters of the Jewish immigrant experience in America. At a time when boxing mattered to society far more than it does today, Jewish people were earning the attention and respect of their fellow citizens in the prize ring.”

In some respects, “Stars in the Ring” is a social history of boxing as seen through the Jewish experience. Drawing parallels with society as a whole, Silver recounts, “The Golden Age of the Jewish boxer in America coincided with the Golden Age of the Jewish gangster. Both came from the same gritty rough-and-tumble city streets, and their worlds often intersected. In 1921, Jews represented 14 percent of New York State’s prison population and Jewish women accounted for 20 percent of all female prisoners in New York State.”

Meanwhile, by the mid-1920s, Jewish boxers were so popular that some non-Jewish fighters changed their names to Jewish-sounding ones to advance their ring career. And extending Silver’s “Golden Age” by 10 years, it’s worth running some numbers regarding Madison Square Garden, which was then “The Mecca of Boxing.” In the first five decades of the 20th century, the Garden hosted 866 fight cards. Two hundred forty of those cards featured at least one Jewish fighter in the main event.

The heart of “Stars in the Ring” consists of mini-biographies of 166 Jewish boxers. It’s not a book to be read straight through in one or two sittings. The profiles tend to blend together. But it’s a good all-in-one reference work on little-known Jewish fighters and their more famous brethren like Abe Atell, Joe Choynski, Ted “Kid” Lewis, Jackie “Kid” Berg, Barney Ross and “Slapsie Maxie” Rosenbloom (who author Philip Roth called “a more miraculous Jewish phenomenon than Albert Einstein”).

There are also interesting nuggets of information on Jewish boxers whose ring exploits were modest at best. For example, a Jewish adolescent growing up on Long Island won 22 of 26 amateur bouts, left the sport for good and later looked back on his years in boxing with the thought, “I must have been out of my mind. But I really enjoyed it while I was doing it.”

His name? Billy Joel.

And Silver pays special attention to the man who, mixing religious metaphors, could be labeled the patron saint of Jewish boxers: lightweight great Benny Leonard.

Silver calls Leonard “the most famous Jew in America” in the 1920s and “the gold standard to which all other Jewish boxers are compared.” He also observes, “Not only was Benny Leonard one of the greatest boxers who ever lived, he was the first Jewish superstar of the mass media age and the first Jewish-American pop culture icon. Leonard’s conduct in and out of the ring and his impeccable public image stood as the refutation of the immigrants’ anxiety that boxing would suck their children into a criminal underworld or somehow undermine the very rationale for fleeing to the Golden Land. Leonard legitimized boxing as an acceptable Jewish pursuit.”

But times change. Inevitably, social and economic progress put an end to the Golden Age of Jewish boxing. That leaves Silver to write, “As the last Jewish boxers of the Golden Age die off, it becomes even more important to document their accomplishments so that future generations can acknowledge and appreciate how a people with no athletic traditions and with so many doors closed to them used their intelligence and drive to open another door to opportunity and eventually dominate, both as athletes and entrepreneurs, what was for several decades the most popular sport in America.”

Thomas Hauser can be reached by email at [email protected]. His most recent book (“A Hurting Sport”) was published by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism.