The two fights that changed the definition of boxing “greatness”

In sports the word “greatness” is a singular concept that carries enormous power and influence. Ideally, it’s also a word that should be used sparingly, for if too many athletes and achievements are defined as such, the impact of the genuine article would be unfairly diminished.

Like beauty, however, greatness is open to interpretation and shifting definitions. What was considered beautiful and excellent in past sporting eras would be deemed awkward and obsolete today. For example, the “power sweep” as run by members of the 1960s Green Bay Packers would be no match physically for the size, speed and sophistication of today’s defensive stars. Yet those Packers will always be held in high esteem historically because they won five NFL championships in the decade and they excelled in the game as it was played then. The proof? The Super Bowl trophy is named after Vince Lombardi, the coach of those teams, and any thought of changing it would be considered blasphemous.

In baseball, we’ll likely never again see a pitcher win his 300th game thanks to five-man pitching rotations, carefully monitored pitch counts and six-inning starts backed by waves of relievers. Thus, the accomplishments of Cy Young, Lefty Grove, Nolan Ryan and Greg Maddux gain even more stature but because of the way the sport is played today, the careers of aces like Clayton Kershaw, Madison Bumgarner and Jake Arrieta must be judged differently because their win totals will pale in comparison to their predecessors.

In the NBA, the relevance of a true center has been minimized in favor of dazzling ball movement and three-point shooting prowess, a formula that led the Golden State Warriors to a championship last season and a record 73 wins the following regular season. Therefore, centers such as Dwight Howard, Marc Gasol, Al Jefferson, Joachim Noah and Roy Hibbert will not get within light years of the stats compiled by Wilt Chamberlain, Bill Russell and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. Yet they are regarded as the best of today within the changed structure of the game.

In this regard, boxing is in much better shape in one respect: Because the basic assortment of punches hasn’t changed in more than a century, direct statistical comparisons between fighters of different eras can be made as long as enough complete footage of their fights is available. But in another respect – judging which fighters are truly great – the task has become more difficult, mainly because of the proliferation of multiple-division champions.

For the first nine decades of the modern era, a great boxing champion was defined as one that dominated a single weight class for years on end, moving up only after cleaning out his division, being dethroned or surrendering to the forces of age and nature. The desire to remain king of a single hill was a potent incentive, so much so that lower-weight fighters such as bantamweights Eder Jofre and Lupe Pintor and lightweight Roberto Duran were willing to endure tortuous weight-making regimens just to extend their championship reigns – and add to their legacies and bank accounts.

Back then, few fighters ever thought about capturing world titles in three weight classes because that was the province of the genuine boxing gods. After Bob Fitzsimmons became the first to do so in 1903 (middleweight, heavyweight, light heavyweight) only three other fighters had duplicated “Ruby Robert’s” feat over the next 35 years: Tony Canzoneri in April 1931 (featherweight, lightweight and junior welterweight), Barney Ross in May 1934 (lightweight, junior welterweight and welterweight) and the immortal Henry Armstrong in August 1938 (featherweight, welterweight and lightweight, all of which, for a short time, he held simultaneously). Incredibly, that Mount Rushmore of three-title immortals remained unchanged for nearly 43 years.

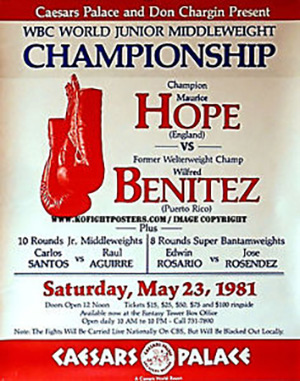

Thirty five years ago this month, the first of two fights that would forever change boxing’s mindset took  place at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas – the electrifying one-punch 12th-round knockout scored by former junior welterweight and welterweight champion Wilfred Benitez to seize Maurice Hope’s WBC super welterweight title. The second fight occurred just 28 days later when former featherweight and junior lightweight champion Alexis Arguello out-pointed WBC lightweight king Jim Watt. The close proximity of the two events – and the media notoriety each man’s victory generated – planted a seed that not only flourished but did so to the point of influencing several generations of successors. The numerical proof will be detailed later, but for now here’s a closer examination of the attitude-shifting matches:

place at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas – the electrifying one-punch 12th-round knockout scored by former junior welterweight and welterweight champion Wilfred Benitez to seize Maurice Hope’s WBC super welterweight title. The second fight occurred just 28 days later when former featherweight and junior lightweight champion Alexis Arguello out-pointed WBC lightweight king Jim Watt. The close proximity of the two events – and the media notoriety each man’s victory generated – planted a seed that not only flourished but did so to the point of influencing several generations of successors. The numerical proof will be detailed later, but for now here’s a closer examination of the attitude-shifting matches:

*

Although he was the challenger, Benitez, who was making just $175,000 to Hope’s $450,000, was perceived as the A-side of the equation and the 2-to-1 betting odds in his favor reflected his standing with the public in relation to Hope. There was ample reason for their thinking: Though just 22, Benitez had been on the world stage for more than five years and his “hook” was that he was boxing’s equivalent of Mozart. His introduction to the highest levels of the sport was nothing short of astonishing; on March 6, 1976 Benitez, at just 17 years 180 days, miraculously out-boxed long-reigning WBA junior welterweight champion Antonio Cervantes over 15 rounds to become the youngest world champion in the sport’s history – a record Benitez still holds more than 40 years later. His poise under pressure and his superlative technique that night were light years beyond his chronological age.

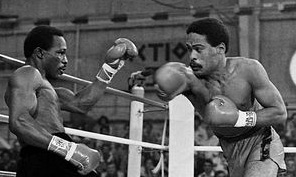

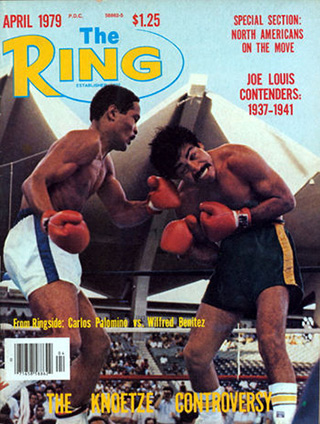

The man called “El Radar” and “The Bible of Boxing” proved he was no one-hit wonder as he notched two defenses of the WBA title and added a third of the New York State Athletic Commission version of the belt against Ray Chavez Guerrero after the WBA stripped him for not accepting a rematch with Cervantes. Five fights later Benitez dethroned another long-reigning titlist in Carlos Palomino to win his second title, the WBC welterweight belt. Again, the decision was split but like the Cervantes fight Benitez’s superiority inside the ring was beyond question.

The man called “El Radar” and “The Bible of Boxing” proved he was no one-hit wonder as he notched two defenses of the WBA title and added a third of the New York State Athletic Commission version of the belt against Ray Chavez Guerrero after the WBA stripped him for not accepting a rematch with Cervantes. Five fights later Benitez dethroned another long-reigning titlist in Carlos Palomino to win his second title, the WBC welterweight belt. Again, the decision was split but like the Cervantes fight Benitez’s superiority inside the ring was beyond question.

Benitez’s welterweight reign was short-lived as he lost to Sugar Ray Leonard in his second defense but wins over Johnny Turner (KO 9), Tony Chiaverini (KO 8) and Pete Ranzany (W 10) at 154 pounds earned Benitez the chance at Hope, a skilled southpaw who was making the fourth defense of the belt he won from Rocky Mattioli three years earlier.

Born in Antigua, Hope moved to England at a young age and learned to box there. Following a successful amateur career he turned pro in June 1973 with an eight-round decision over 24-fight veteran John Smith. Hope’s road to the top wasn’t always smooth; he lost an eight-rounder to Mickey Flynn in his fifth outing and 10 fights later he suffered an eighth-round stoppage to Bunny Sterling for the vacant British middleweight title. After that Hope decided to campaign at 154 and he earned instant success as he won the British junior middleweight title against Larry Paul just 112 days after the Sterling loss.

From there he went 13-0-1 with the only blemish a draw against then-WBC champion Eckhard Dagge in Berlin. On March 4, 1979 Hope met Dagge’s successor, Australian-based Italian Rocky Mattioli, whose assimilation was so complete that he spoke with an Aussie accent. Fighting Mattioli in San Remo, Italy, the stylish Hope dropped the champion just 15 seconds into the fight but during the fall Mattioli landed heavily on his right arm, breaking two bones in his forearm and effectively rendering it useless for the remainder of the fight, which ended with a ninth-round TKO.

The injury offered a rationale for a rematch 16 months later, this time in London. Hope was fighting for the first time since undergoing retinal surgery but any doubts regarding his fitness to fight were erased as he produced a career-best performance. His rapier right jab sliced through Mattioli’s guard and his stinging left crosses and gorgeous combinations connected with frightening regularity. Mattioli’s toughness was such that the fight lasted deep into the 11th, where a blizzard of unanswered blows prompted referee Arthur Mercante to intervene at the 2:52 mark.

Four months later Hope retained the title on points but only after surviving a stirring challenge from Argentine Carlos Herrera. After that, he signed to defend against Benitez, easily the most high-profile opponent of his career. With the fight being staged in Las Vegas Hope came up with a master plan: Beat Benitez to retain the title, then marry his fiancee the next day at one of the Strip’s numerous wedding chapels.

Four months later Hope retained the title on points but only after surviving a stirring challenge from Argentine Carlos Herrera. After that, he signed to defend against Benitez, easily the most high-profile opponent of his career. With the fight being staged in Las Vegas Hope came up with a master plan: Beat Benitez to retain the title, then marry his fiancee the next day at one of the Strip’s numerous wedding chapels.

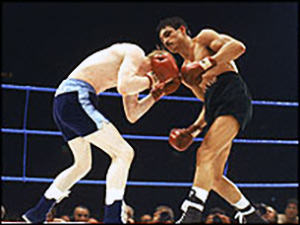

With a loyal contingent of Brits chanting “let’s go Super Mo,” Hope fought evenly with Benitez, whose opening blows were haphazardly chosen and thrown with uncharacteristic wildness. Benitez employed his version of the “rope-a-dope” from time to time but while Benitez scored with counterpunches Hope somewhat negated the tactic by landing his vaunted jab, then skipping back to reset. Unlike the Mattioli fight in which Hope played counter-puncher, the champion was the willing aggressor and that eagerness to come forward earned him the first three rounds on Joe Swessel’s card.

Midway through the fourth Hope opened a cut on the corner of Benitez’s right eye and the challenger responded by briefly turning southpaw, then opening a cut inside Hope’s mouth.

The bout remained close through five rounds but starting in the sixth Benitez started asserting himself. Curiously moving to his right instead of advancing forward as he had been, the southpaw Hope absorbed more of the challenger’s right hands, one of which visibly shook Hope in the final minute. A second right to the point of the chin sent Hope reeling toward the strands and the challenger jumped in behind a fusillade of blows.

From there Benitez separated himself from Hope, both in terms of skill and on the scorecards. A lead right to the chin in the closing seconds of round 10 sent Hope skidding to the floor but the champion regained his feet with little trouble and well within referee Richard Greene’s count.

Such would not be the case two rounds later when Benitez landed the single greatest punch of his Hall of Fame career. As Hope slid to his left along the ropes Benitez deked with his left shoulder, then unleashed a lethal overhand right to the jaw that had Hope falling to the floor in sections. Benitez knew that his quest for a third championship had just ended and he communicated that confidence by flashing a wide smile even before Hope had hit the floor.

Greene didn’t bother to finish his 10 count and within moments medical personnel began tending to him. The Associated Press reported that it took three minutes for Dr. Donald Romeo and Hope’s handlers to revive the fighter, then another five minutes to get the former champion to his feet. The punch had knocked out one of Hope’s teeth and prompted an overnight stay at Valley Hospital. For the record, Hope followed through with the wedding.

Before this fight, Benitez was regarded as a good fighter but not yet a great champion because his reigns at 140 and 147 were brief in comparison to the past greats. But the impact of that explosive overhand right begat ramifications that carried far beyond a knockout victory, both for Benitez’s career and for the sport moving forward.

Before this fight, Benitez was regarded as a good fighter but not yet a great champion because his reigns at 140 and 147 were brief in comparison to the past greats. But the impact of that explosive overhand right begat ramifications that carried far beyond a knockout victory, both for Benitez’s career and for the sport moving forward.

In terms of the former, the perception of Benitez instantly changed for the better. By capturing a title in a third weight class, Benitez had reached what many at the time considered an Everest-like summit in terms of historic achievement and, at 22 years 259 days, the Puerto Rican wunderkind was the second-youngest to plant the flag (Canzoneri was 85 days younger). But less than a month after Benitez toppled Hope, another fighter who scaled 18.75 pounds lighter would seek to duplicate this feat.

*

As was the case with Benitez, former featherweight and super featherweight champion Alexis Arguello was favored to dethrone WBC lightweight king Jim Watt, who, like Hope, was a southpaw. While he was beloved in Scotland, Watt had a much tougher time gaining respect elsewhere, especially in America. At first he was viewed as a caretaker champion, for he won the WBC belt vacated by Roberto Duran by stopping Alfredo Pitalua in 12 rounds, then defending against Roberto Vasquez (KO 9) and Charlie Nash (KO 4) in a Closet Classic tear-up. Most observers expected Watt’s reign to end on June 7, 1980 when he met 1976 Olympic gold medalist Howard Davis Jr., whose supersonic hand and foot speed seemed perfectly matched against Watt’s notoriously cut-prone skin. But the gritty Glaswegian defied the “experts” by out-boxing and out-foxing the American en route to a unanimous decision.

Five months later another American trekked to the cacophonous lion’s den of Kelvin Hall and this Yank, Oklahoma power-hitter Sean O’Grady, boasted an eye-popping 73-1 (64) record that included a 44-fight winning streak. Once again, Watt’s educated right jab – and the crown of his skull – opened cuts on O’Grady’s fragile face. One final clash of heads – replays were inconclusive as to which man initiated it – created a horrific vertical gash that split the challenger’s forehead wide open. The flow of crimson quickly reached dangerous levels and the fight was stopped at 2:37 of round 12.

Next up was Arguello, a two-division champ that prospered at 126 before vacating due to weight-making considerations (not surprising given his 5-foot-10 frame) but thrived after winning the WBC 130-pound title from long-time titlist Alfredo Escalera in the “Bloody Battle of Bayamon.” The elegant Nicaraguan with the steely fists registered eight defenses (seven by KO) before vacating his second belt and following a three-round KO over common foe Roberto Vasquez Arguello entered the ring against Watt with a sterling ring record (66-5, 54) and an even more sterling reputation as a human being. Words like “gracious,” “kind” and “classy” were almost universally used to describe “The Explosive Thin Man,” who was installed as a solid 5-to-2 favorite despite the fight being staged in Watt-friendly London.

Next up was Arguello, a two-division champ that prospered at 126 before vacating due to weight-making considerations (not surprising given his 5-foot-10 frame) but thrived after winning the WBC 130-pound title from long-time titlist Alfredo Escalera in the “Bloody Battle of Bayamon.” The elegant Nicaraguan with the steely fists registered eight defenses (seven by KO) before vacating his second belt and following a three-round KO over common foe Roberto Vasquez Arguello entered the ring against Watt with a sterling ring record (66-5, 54) and an even more sterling reputation as a human being. Words like “gracious,” “kind” and “classy” were almost universally used to describe “The Explosive Thin Man,” who was installed as a solid 5-to-2 favorite despite the fight being staged in Watt-friendly London.

The proud 32-year-old Watt produced his best but his best was not nearly good enough to beat Arguello, who skillfully exploited his height and reach by landing razor-sharp blows and intelligently mixing his attack between head and body. Arguello’s hook to the jaw produced the fight’s only knockdown in round seven and the remainder of the fight illustrated the difference between a very good fighter and a certified legend. At fight’s end Watt, ever the sportsman, initiated a hearty embrace. The scores were unanimous (147-143 twice, 147-137) and aptly represented the action that preceded it.

*

The combination of Benitez’s and Arguello’s elevated standing in the sport and the special attention their shared accomplishment garnered from the mass media resulted in an attitudinal sea change in which collecting belts in multiple weight classes was the new measuring stick of greatness. Consider: Since Arguello’s triumph over Watt 36 more fighters have become three-division champions, 21 of which were crowned since May 2001 and 13 since September 2008. In fact, 2015 saw two more join the ranks – Kazuto Ioka in April and Akira Yaegashi in December. With triple-champions being created by the dozen the accomplishment has been so watered down that it barely rates a mention anymore.

With a pair of triple champions in the game, Arguello tried to one-up Benitez by moving up to 140 to challenging for a fourth division title, an objective only Armstrong had dared to attempt. With Armstrong at ringside, Arguello lost to Aaron Pryor with one of the more frightful knockouts of the 1980s, then lost the rematch 10 months later.

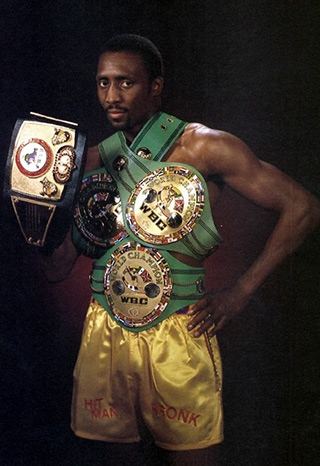

From almost the start of his career Thomas Hearns aimed to become boxing’s first four-division champion and in back-to-back fights in 1987 he achieved his dream in sensational style. In March a spectacularly chiseled 173¼-pound Hearns scored six knockdowns of Dennis Andries to win his third belt via 10th-round TKO, then in October he pared down to 159¾ and notched impressive but occasionally perilous fourth-round knockout of Juan Domingo Roldan to add the vacant WBC middleweight strap.

From almost the start of his career Thomas Hearns aimed to become boxing’s first four-division champion and in back-to-back fights in 1987 he achieved his dream in sensational style. In March a spectacularly chiseled 173¼-pound Hearns scored six knockdowns of Dennis Andries to win his third belt via 10th-round TKO, then in October he pared down to 159¾ and notched impressive but occasionally perilous fourth-round knockout of Juan Domingo Roldan to add the vacant WBC middleweight strap.

While Hearns’ titular grand slam made big news in 1987, even that accomplishment eventually lost its impact. Thirteen more fighters have become quadruple champions in 29 years since Hearns’ triumph and if any fighter epitomizes the speed and ease with which titles can be acquired it is Adrien Broner. Broner won three of his belts in a six-fight period between November 2011 and June 2013, then won his fourth in November 2015. Three of his four belts were vacant at the time he won them and his opponent for the final title, Khabib Allakhverdiev, was coming off a loss and was fighting for the first time in nearly 18 months. Even worse, Broner lost two titles on the scale and his four reigns produced just two successful defenses.

To further illustrate the diminished meaning of multiple championships, five fighters have won titles in five weight classes and two (Oscar de la Hoya and Manny Pacquiao) have won recognized belts in six. A more liberal interpretation would number Pacquiao’s conquered weight classes at eight – more than half of the sport’s 17 divisions.

Back in the day, the “glory shot” would be a photo of a fighter striking a pose with a single belt strapped around his waist. Unseen, but definitely felt, was the reputation and respect that picture represented. He was the one and only champion and his long record of success, especially if adorned by knockouts, was enough to send the message to his peers and to his public: I am the king of this hill and I am ready to fight all those who challenge me. And know this: I am not going anywhere until either someone takes this from me or after I leave this realm on my terms.

In the post Benitez-Arguello era, the glamour shot is that of a fighter with three belts adorning his body – one strapped over each shoulder and the other adorning his waist. If he’s fortunate enough, the picture also would include members of his team holding up all the other belts he’s earned over the years. Like a nation staging a parade of military weaponry on the streets of its capital city, that photo depicts an unmistakable show of force and accomplishment. Today there is no room for subtlety or modesty; the more baubles, the better.

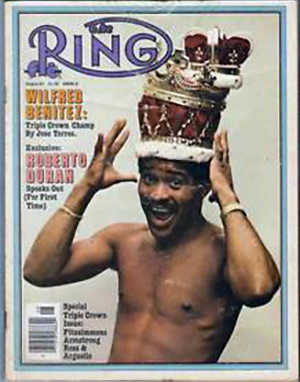

In fact THE RING itself may well have ignited this visual, for the cover of the August 1981 issue depicts a beaming Benitez straining to balance the three crowns precariously sitting atop his head. Billed as a “special triple crown issue,” the magazine published profiles of Fitzsimmons and Armstrong as well as articles on Ross and Arguello as well as a full-page cartoon by Charlie McGill paying homage to Benitez and Arguello on the top half and the other four on the bottom half. A new era had dawned – and a new mindset was about to take hold.

In fact THE RING itself may well have ignited this visual, for the cover of the August 1981 issue depicts a beaming Benitez straining to balance the three crowns precariously sitting atop his head. Billed as a “special triple crown issue,” the magazine published profiles of Fitzsimmons and Armstrong as well as articles on Ross and Arguello as well as a full-page cartoon by Charlie McGill paying homage to Benitez and Arguello on the top half and the other four on the bottom half. A new era had dawned – and a new mindset was about to take hold.

But while this nomadic trend is prevalent, it isn’t universal. In the 35 years that have elapsed since Benitez-Hope a handful of champions have upheld the ideals of a seemingly bygone era. Bernard Hopkins held the IBF version of the middleweight title for more than 10 years, eventually became the first (and so far only) undisputed champion of the four-belt era and registered a record 20 defenses before Jermain Taylor dethroned him in 2005. Others of his ilk include Dariusz Michalczewski (23 defenses of the WBO light heavyweight title), Ricardo Lopez (21 defenses of the WBC minimumweight title), Pongsaklek Wonjongkam (21 defenses of the WBC flyweight title in two reigns), Sven Ottke (21 defenses of the IBF super middleweight title), Joe Calzaghe (21 defenses of the WBO super middleweight belt), Ratanapol Sor Vorapin (20 defenses of the IBF minimumweight title), Virgil Hill (20 defenses of the WBA light heavyweight title in two reigns), Khaosai Galaxy (19 defenses of the WBA super flyweight belt) and Myung Woo Yuh (18 defenses of the WBA junior flyweight belt over two reigns).

Among current champions Gennady Golovkin (11 defenses of the “full” WBA middleweight title, 16 if one includes his time as “interim” titlist) has resisted the calls for him to move up to 168 and 175, for he is content reigning over the 160-pounders as Hopkins, Marvelous Marvin Hagler and Carlos Monzon did before him. Recently dethroned WBA super featherweight king Takashi Uchiyama recorded 11 defenses over his six-year reign while WBC bantamweight king Shinsuke Yamanaka retained his title for the 10th time in March and WBO junior flyweight monarch Donnie Nietes is about to make the ninth defense of his nearly five-year reign.

These fighters, however, will likely remain the exception rather than the rule. That’s because on May 23, 1981 the dividing line between old and new had been drawn – a line shining with neon-like intensity that may remain for the rest of time.

*

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, West Virginia. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 15 writing awards, including 12 in the last six years and two first-place awards since 2011. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics.” To order, please visit Amazon.com. To contact Groves, use the e-mail [email protected].