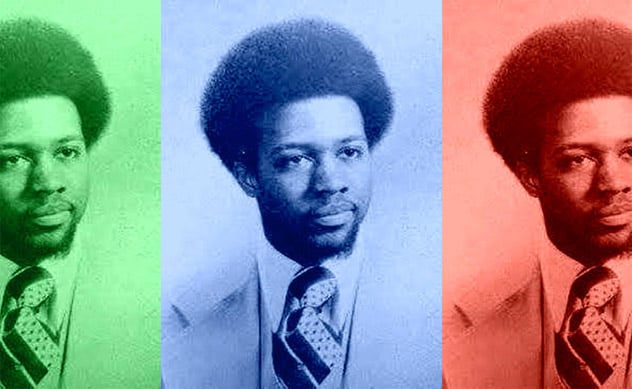

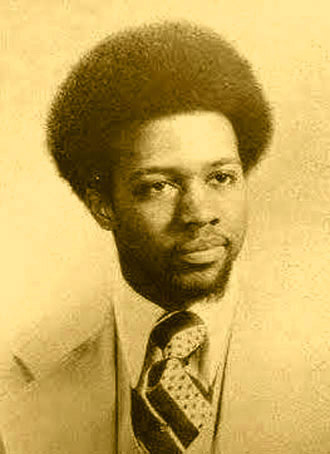

What we know about Al Haymon: Part III

THE RING’S Thomas Hauser in this special series sheds light on the powerful and mysterious boxing impresario Al Haymon and Premier Boxing Champions. Third of five parts.

The consensus is that Al Haymon is pro-fighter. Whether he’s pro-investor is a separate issue.

The consensus is that Al Haymon is pro-fighter. Whether he’s pro-investor is a separate issue.

Haymon has gotten to where he is in boxing by making alliances with bankers. His first banker was HBO Sports. Showtime filled the void when that relationship ended. Now he has found venture capitalists who are willing to underwrite his plans on an extravagant scale.

Haymon believed that, unlike most sports, boxing can be transformed by a drop in the ocean of water that flows through the venture capital market every day. His plan is based on the premise that there’s a hidden audience for boxing that will watch fights on “free” television in numbers large enough to generate profitable ad sales. In furtherance of this idea, he pursued venture capital from myriad sources and got it from an asset management company called Waddell & Reed.

Bill King of Sports Business Journal began the process of publicly fleshing out the financial muscle behind Haymon’s plans with an analysis of Premier Boxing Champions that was posted on April 20, 2015.

“The struggle began with finding out who to contact in the first place,” King recalls. “You can’t just call Al. I went to the first PBC press conference in New York (on Jan. 14, 2015) which was for a show on NBC. There was a guy from Chicago who was listed as a PR contact so I emailed him. And Ryan Caldwell (of Waddell & Reed) was at the press conference so I started doing research on him.

“My pitch to them,” King explains, “was if PBC is going to be on network TV, we’re a vehicle for you to improve your credibility with network executives and advertisers. And we have a reputation for splitting things down the middle rather than taking sides. Finally, I was told, ‘Come to the first PBC event (in Las Vegas on March 7, 2015) and someone will talk with you.’ My request was to talk with Al but they said that was unlikely. And Al wouldn’t talk with me. All I got from him was a hello and a handshake to acknowledge that he knew who I was.

“I had to do a lot of digging to get the financials,” King continues. “There’s a lot more available now than there was then. Ryan Caldwell agreed to discuss the venture with me but declined to reveal financials.”

King based some of his research on quarterly filings with the Securities Exchange Commission made by an entity called the Ivy Asset Strategy Fund, which Caldwell co-managed for Waddell & Reed. The Ivy Asset Strategy Fund included among its holdings an investment designated as “Media Group Holdings LLC, Series H,” which King confirmed was with Haymon.

Come on, four hundred million dollars? You can’t spend that kind of money, not even in boxing.

“Ivy Asset Strategy’s holdings list,” King wrote in Sports Business Journal, “included a $371.3 million investment in the company. A second Waddell fund, WRA Asset Strategy, listed an investment of $42.2 million. A third fund, Ivy Funds VIP Asset Strategy, showed holdings of $18.5 million. Together they invested $432 million. It is likely other funds run by Waddell also have invested, a source familiar with fund management said, although their positions likely would be smaller.”

King also revealed, “While Caldwell would not discuss funding specifically, he said that Waddell & Reed invested considerably more than Haymon requested in the initial business plan to build a brand and an audience, a proof-of-concept phase that would then enable him to cash in on the rights fees that continue to trend upward across sports.”

“Al said, ‘I think I can pull this off for X,'” Caldwell told King. “And I turned around and said, ‘Absolutely not. It’s X-plus or we don’t do it.’ You have to be capitalized for three to five years to do this, to weather the storm. Because in some regards you’re going to be the irrational player for a while. You’re turning the model completely upside down.” ÔÇ¿ÔÇ¿

As noted in Part II of this series, Haymon is paying unusually large purses to fighters. That in and of itself is not a problem. HBO paid above-market license fees to promoters for years to lure fights away from ABC, CBS and NBC. George Steinbrenner paid above-market salaries to free agents to reestablish the New York Yankees dynasty. You spend money to make money.

That said, a conflict of interest seems to be built into Haymon’s methodology. He has a fiduciary duty to the fighters he manages to get them the most money possible. But he also has a fiduciary duty to his investors to cap expenses and maximize their return on investment. After all, this isn’t business as usual but it is business. The idea is to make money for the investors. And right now, Premier Boxing Champions appears to be hemorrhaging money, not making it.

Haymon assumed that income from Premier Boxing Champions telecasts would come initially from multiple sources, including advertising, ticket sales, sponsorships and license fees for foreign rights. His managerial fee is also believed to be part of the revenue stream for investors.

More importantly, Haymon predicted that, after the time buys end, television networks will pay significant license fees for PBC fights. At the moment, that prospect looks bleak.

On May 11, 1977, 48 million viewers watched Ken Norton defeat Duane Bobick in a fight televised by NBC. Four months later, Muhammad Ali triumped over Earnie Shavers in a bout seen by almost 100 million people. Those days are long gone. But even in today’s fractured digital environment, PBC’s ratings have been a disappointment.

PBC’s March 7, 2015, debut telecast on NBC headlined by Keith Thurman vs. Robert Guerrero averaged 3.37 million viewers. That’s a good number but it soon tapered off. When Deontay Wilder fought Johnann Duhaupas on NBC in prime time on Sept. 26, there were 2.18 million viewers. Sports Media Watch noted that this was the smallest audience for a prime-time boxing or MMA event on network television since 2008, a period that included 25 telecasts.

Carlos Acevedo of TheCruelestSport.com further analyzed the numbers and suggested, “Compare that to “American Ninja Warrior,” which aired on NBC two weeks earlier and drew over six million viewers.”

Ratings for Premier Boxing Champions telecasts on CBS, ESPN, Spike, Bounce and Fox have also disappointed. CBS has yet to match the 1.6 million average viewership that Adonis Stevenson vs. Sakio Bika engendered in its initial PBC telecast on April 4, 2015.

When Keith Thurman returned to the airwaves against Luis Collazo on July 11, 2015, to inaugurate PBC boxing on ESPN, the telecast averaged 799,000 viewers.

Spike’s first PBC telecast (Andre Berto vs Josesito Lopez on March 13, 2015) was also its highest-rated, drawing an average of 869,000 viewers. The eight PBC telecasts on Spike since then have fallen short of that mark, hitting bottom with Andrzej Fonfara vs. Nathan Cleverly (315,000 viewers) on Oct. 16. The Los Angeles Times reported that Spike’s PBC numbers were below the numbers for the same Friday-evening slot in 2014, when the network televised “Bellator” mixed martial arts and reruns of “Cops.”

The ratings for PBC telecasts on FoxSports1 have been mediocre, cratering with a Feb. 2, 2016, telecast that averaged 76,000 viewers.

Broadcast television networks and most cable channels are in the business of selling advertising. They contract for time buys when their marketing department says it can’t sell enough ads to make particular programming profitable. In a sense, the time buys are a substitute for bulk ad sales.

As noted by Bill King, the most logical way for Haymon to sell ad time across so many networks is to have one group coordinate the selling. That way, there aren’t six different networks competing against each other to sell the same product.

In that regard, King reported, “To approach the broader sports sponsorship community, PBC hired SJX Partners to create integrated packages that include spots during fights, branding on the ring, digital assets, tickets and hospitality; a package rare in boxing because it has been off advertiser-supported TV for so long. PBC also brought in Bruce Binkow, former chief operating officer of Golden Boy Promotions, to advise it on operational matters and maintain relationships with brands already in the sport.”

But it has been a hard sell.

Sports seasons have expanded and are continuing to expand. The Super Bowl is now played in February. The World Series routinely extends into November. If the 2016 NBA Finals go the distance, the final game will be contested on June 19. And the TV calendar is filled with other high-profile events in sports like tennis and golf. That means there’s no time when boxing is alone on the stage. And advertisers have limited budgets.

It’s easy for TV networks to sell advertising for NFL programming. Ditto for other major sports and events like the Masters and Wimbledon. Advertising for boxing is a hard sell. Ratings are low. Many advertisers don’t want their product associated with the less savory aspects of the sport. And there’s another problem: In most sports, advertisers don’t have to worry about 2-minute knockouts. In boxing, at any moment – BOOM – the fight might end. This contingency makes boxing compelling programming for premium cable networks that are built on subscriptions but it’s a problem for networks that rely on advertising.

Many advertisers don’t want their product associated with the less savory aspects of the sport. And there’s another problem … In boxing, at any moment – BOOM – the fight might end.

Haymon now has the burden of selling advertising for programming that advertisers have resisted for decades. On Feb. 3, 2016, the Los Angeles Times reported, “Television advertising tracking firm Kantar Media said (PBC) collected $12.5 million in total ad revenue from 27 fight telecasts from March through September (2015), an average of $462,963 per show”

That’s a low number.

Moreover, every successful sport sells tickets for its live events and makes good money from those sales. For PBC, on-site ticket sales seem to be an afterthought. PBC sometimes even loses money on the venue once the cost of opening the arena is set against ticket receipts.

“‘PBC’ could stand for ‘Premier Boxing Comps,'” Steve Kim of Undisputed Champion Network wrote last year in commenting on Haymon’s practice of giving away tickets to paper the house and employing seat-filling services.

To that, promoter Gary Shaw adds, “They’ve given away so many free tickets to paper the house that it’s become increasingly hard for the rest of us to sell tickets because people are waiting for freebies.”

Meanwhile, the value of Waddell & Reed’s investment in Haymon’s boxing entities is shrinking.

Filings with the Securities Exchange Commission suggest that a total of $528,481,000 was made available to Haymon. As of Dec. 31, 2015, that investment was valued at $82,354,000 – a drop of 84 percent in investment value.

Richard Schaefer understands venture capital and boxing. Also, in the past, the former Swiss banker and one-time CEO of Golden Boy Enterprises worked closely with Haymon.

“I see the numbers,” Schaefer acknowledges. “People say, ‘Al has spent three hundred million dollars. Al has spent four hundred million dollars.’ But those numbers don’t mean the money has been spent. Those numbers are valuations of the assets. Assets can be valued in different ways. Assets can be written down for tax purposes. The value of a (non-monetary) asset like good will can change over time. Come on, four hundred million dollars? You can’t spend that kind of money, not even in boxing.”

In other words, the initial $528 million number could have included non-monetary assets such as fighter contracts and the value of the PBC brand. And the $82 million figure could reflect a downward evaluation of these non-monetary assets in addition to a lessening of cash on hand.

That said, the $82 million valuation as of Dec. 31 is presumed to be less than what Haymon has spent so far. There has been a significant cash burn. A war chest that was intended to underwrite PBC’s operation for three or four years has dramatically diminished. And there are no offsetting revenue streams in sight.

Meanwhile, as reported by the Wall Street Journal, Waddell & Reed has “hit a rough patch.” Investors have withdrawn billions of dollars from its funds and Waddell & Reed stock has dropped from a 12-month high of $51.23 to $25.79 a share as of March 17, 2016.

Top Rank CEO Bob Arum calls Premier Boxing Champions “boxing’s version of a Bernard Madoff Ponzi scheme” and has bemoaned the “fact” that “widows and orphans are losing their life savings in this horrible, horrible scheme.”

That characterization seems a bit extreme. Moreover, it’s likely that Haymon’s business plan warned investors that the venture was highly speculative and that they could lose all of their investment.

Still, if hundreds of millions of dollars disappear, not all of the investors will go quietly. An investors suit against Waddell & Reed and the Haymon entities at some point in the future is possible.

It’s not publicly known how Haymon is compensated by the companies under his control, nor is it clear whether any of the money being spent by the companies goes out to third parties and then comes back to him. Neither Haymon nor any of the companies under his control have stated publicly how he is compensated for his work.

The role of Ryan Caldwell, who left Waddell & Reed last year to join Haymon as chief operating officer of PBC and then departed from PBC soon after to form his own asset management company, is also subject to conjecture.

On Feb. 5, 2016, a New York lawyer named Jake Zamansky sent out a press release announcing that his law firm was “investigating the departure of Mr. Caldwell (from Waddell & Reed) and whether the Funds breached duties owed to shareholders.”

Zamansky sounds like a lawyer looking for a plaintiff for a possible class action lawsuit.

It’s not uncommon for an innovative entrepreneur to believe that the prevailing logic in an industry is wrong and should be challenged. Sometimes the entrepreneur is right in that thinking, is wildly successful under a new set of rules and makes hundreds of millions of dollars. And sometimes the entrepreneur fails.

Meanwhile, it’s worth considering the thoughts of one promoter who has been watching Haymon for years:

“I’m not an investment analyst but I know how to count. And so far, the numbers don’t add up. Forget about making a profit. I don’t think Haymon’s investors will get their money back. Everyone agrees that Al isn’t stupid. He’s very smart, a lot smarter than I am. So why is this happening? Follow the money.”

This is the third in a five-part series. Click here for Part I and Part II or Go to Part IV.

Hauser is a consultant with HBO Sports.

Thomas Hauser can be reached by email at [email protected]. His most recent book – A Hurting Sport – was published by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism.