From Henry Hank to Tony Harrison, the Detroit Style lives on

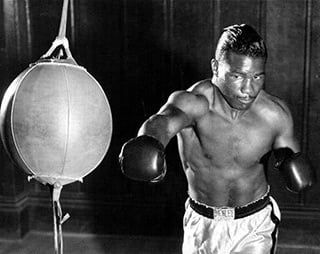

Tony Harrison’s grandfather Henry Hank (left) fought many hall of famers during his near-20 year career in the 1950s and ’60s, including Dick Tiger (right).

There’s no greater endorsement of a fighter today than to label him “old school.”

The idea that they just don’t make ’em like they used to still permeates boxing culture, and is more deeply rooted in the casual fan base that likes to declare the sport “dead” every once in a while.

Whether fighters today are indeed better than they were in past eras is a question that can be answered in many different ways, but there’s no debating that there is a lot to learn from the fighters and teachers of yesteryear. As the years pass by, there are fewer and fewer trainers with a connection to the golden eras, and as a result, the fighters begin to look and behave less and less like they used to.

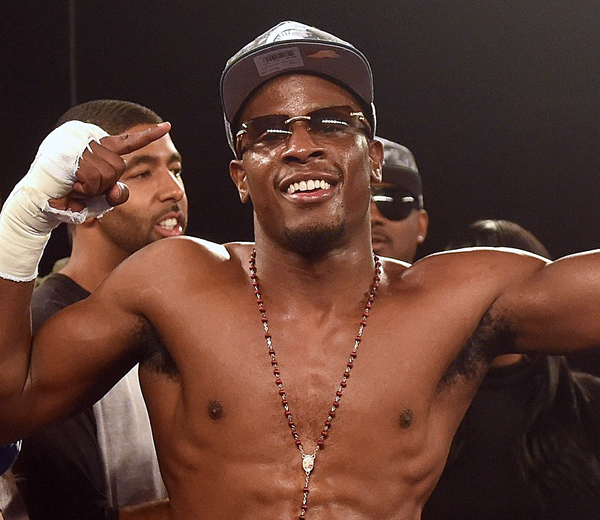

Tony Harrison is one of those few young fighters with a diploma from the old school.

Much has been written about the junior middleweight’s affiliation with the late Emanuel Steward and the famed Kronk Gym. Harrison is regarded as Steward’s last true protege before he passed, and was the fighter Manny openly tabbed as the next superstar in boxing.

However, his bloodlines in the prizefighting ring are often no more than a footnote.

Harrison is the grandson of one of the great television fighters of the 1960s, Henry Hank. It stands to reason that this has been glossed over, because Hank’s importance in Detroit’s boxing history has been largely understated as well. As obviously influential as Joe Louis, Sugar Ray Robinson and the conveyor belt of champions and contenders from the Kronk were on the Motor City scene, Hank was the one carrying the flag for the city on television for the better part of a decade.

Henry Hank

Hank was a devastating power puncher with a touch of finesse, who was amazingly a contender between middleweight and light heavyweight for a full decade. Hammerin’ Henry made his first appearance in the Ring rankings in December of 1959 at 160, and his final appearance at 175 in June of 1969. Though he never received a shot at the world title, in a historically strong era in his weight range, he fought six former or future world champions: Joey Giardello, Jimmy Ellis, Virgil Akins, Joey Giardello, Dick Tiger, Harold Johnson and Bob Foster.

Outside of the ring, Hank was a boisterous personality became infamous for his trash-talking as well. His verbal assault of Hank Casey is legendary, declaring “Casey couldn’t knock me out if I gave him a fun to carry in each hand. If I ever got knocked out by a fighter like him I’d retire.” He was later reprimanded by the California State Athletic Commission for saying he would “break Casey’s neck” at a press conference. During his time away from boxing, he worked as a zookeeper, both during and after his career.

“Chuck Davey, who was a staple of television, was pure Detroit, went to Michigan State and all that, but he was done by ’55. But in terms of a television attraction, Hank took the baton from Chuck Davey,” said Showtime broadcaster and boxing historian Steve Farhood. “The emergence of the Kronk in the late 70s kind of overshadowed everything that came before it in Detroit. People think of Joe Louis, but everything outside of Joe Louis and the Kronk seems to be forgotten.”

His grandson certainly hasn’t forgotten him. While Hank passed away in 2004 and didn’t get to see Tony fight as a professional, he was there for the early days of his amateur career. Though old age and Alzheimer’s had set in, Hank watched from a wheelchair ringside as Harrison stepped through the ropes for the first time in 2002, wearing one of his old ring robes.

“It looked like a prom dress on me,” joked Harrison, who fought under the Henry Hank Boxing Gym banner during his amateur career, and now helps fund and operate the gym in Detroit along with his father Ali Salaam.

Harrison will fight this weekend as part of a special Showtime telecast, as he takes on veteran Fernando Guerrero. The 25-year old is one fight removed from his first professional loss, a TKO at the hands of Willie Nelson in July of 2015. Since then, he bounced back with a victory over Cecil McCalla, but he still insists he’s making adjustments based on his lone setback.

“I wasn’t impressed with myself. No way in a million years was Cecil McCalla supposed to go 10 rounds with me. I felt like I was sharp, but I felt like if I would have pressed the action and not boxed so much the fight wouldn’t have done the distance. But all that is stemming from the loss to Willie Nelson, just trying to get back on the winning side and not taking any chances, but that’s what got me here, taking chances and being a risk-taker,” said Harrison.

Though Harrison feels his hunting for a knockout against Nelson ultimately led to his demise, he sees that as merely a hazard of his occupation. Grandpa got himself into trouble looking for one big shot as well, though his troubles manifested themselves in a different way. Though he was one of the biggest punchers in whatever division he was in at the time, not everyone hit the mat the moment he hit them. Often times he would be criticized for letting fights slip away as he tried too hard for the KO.

That approach also made him compelling television. While there were certainly brilliant boxers with different styles displayed on cable at the time, many TV fighters were crude brawlers. Hank’s crouched stance, with his left hand dangling and right hand carried slightly across his face to parry return fire was a fairly unique sight.

For Saturday’s bout, Harrison is doing more than just summoning the memory of his grandfather, he’s implementing more elements taken directly from him. In addition to his father, Tony’s uncle Amin Salaam is now a part of his camp as well. Amin had the opportunity to train alongside Hank when he was living in New Mexico

“My whole style came from what my Dad learned from him. You see the similarities between me and my Granddad, because that’s what was passed along through the family. But you think my left hand was down then? I damn near got both of my hands down now,” said Harrison, who has clearly inherited the gift of gab.

“The key to having your hands down is really being confident. That’s really all there is to it. It forces you to do things that you wouldn’t do with your hands up. With your hands down, it forces you to move your head. With your hands up, you usually want to just shell up and catch everything. My granddad did a perfect job of that, and of slipping and rolling and catching.”

Of course, there are inherent dangers that come with fighting in what is sometimes called the “Detroit Style.” A low left hand gives you excellent snap on your jab and greater punch variety, but you’ll also get hit if you’re not careful. Hank wasn’t always particularly cautious, but he had an iron chin, having only ever been stopped by the murderous punching Foster.

But in the Harrison family, that’s just the way they’ve always done it.

“When my hands are down, I know I’m gonna take punches, and once I mentally know I’m gonna take the punches, the punches are just there. You hit me, I hit you,” he said.

Now that’s old school.

Corey Erdman is a boxing writer and commentator based in Toronto, ON. Follow him on Twitter @corey_erdman.