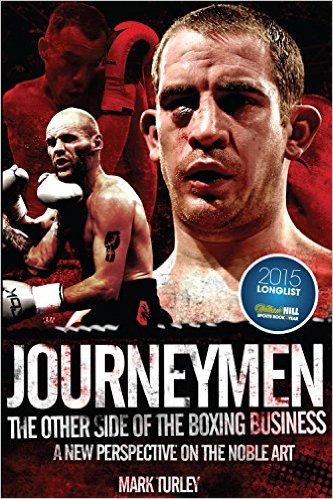

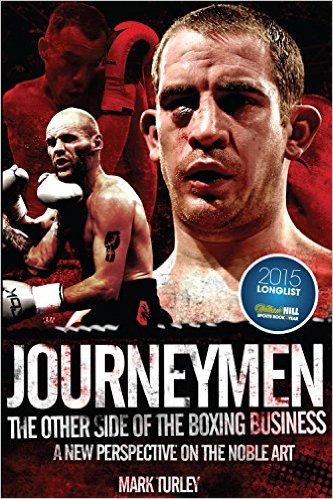

From the Bookshelf: ‘Journeymen’

“Journeymen” by Mark Turley (Pitch Publishing) recounts the story of 10 British fighters who are professional losers. They might bridle at that label. But losing fights is essential to what they do. Turley calls them “journeymen” (which, on this side of the Atlantic, would connote a more respectable ring record). These fighters have records like 0 wins-73 losses-2 draws (Bheki Moyo), 2-51-0 (Robin Deakin), 10-209-7 (Kristian Laight) and 5-125-5 (Matthew Seawright).

“Journeymen” by Mark Turley (Pitch Publishing) recounts the story of 10 British fighters who are professional losers. They might bridle at that label. But losing fights is essential to what they do. Turley calls them “journeymen” (which, on this side of the Atlantic, would connote a more respectable ring record). These fighters have records like 0 wins-73 losses-2 draws (Bheki Moyo), 2-51-0 (Robin Deakin), 10-209-7 (Kristian Laight) and 5-125-5 (Matthew Seawright).

They are often hopelessly outclassed. And when they might be able to put up a competitive fight, they don’t. The referee, who’s usually the sole judge, is in on the arrangement. Should one of these opponents get the better of the house fighter, the referee frequently ignores what happened in the ring and raises the hand of the favorite in victory. The regulatory authorities are negligent and shameless.

“The stories here,” Turley writes, “come from the wrong end of the fight game. It is the elephant in the room of professional pugilism. Most fights at this level have a predetermined outcome. Officially, there is nothing stopping a journeyman [from] going all out for a win and knocking out the home fighter. But if he wants regular work and the paychecks that come with it, he needs to play the game. Keeping busy and avoiding injury are the keys. They fight while holding themselves in check to preserve the status quo.”

“This is how it works,” says James Nesbitt (one of Turley’s subjects, who had a 10-173-4 record at the time of publication). “Before we go out there, I get a quiet word in my ear. ‘Jase, you’ve got to take it easy. This lad’s sold six grand worth of tickets, so we can’t have him losing. If you go out there and knock him out, I promise you, you’re not getting any fights.’ The taking it easy bit happens with most of my fights. I’m not actually trying to win because I’m told not to. And that’s basically what I do to earn my money in boxing. It’s my weekly wage, so I’m going to do what I need to do to keep it coming. I’m not there to win. I’m there to make the fight and give the lad a workout. Any more than that and people get upset.”

Johnny Greaves (4 wins and 96 losses) has similar thoughts. “For me,” Greaves says, “being a paid oppponent was the obvious choice to make. I knew I was never going to be a world champion. Going down the journeyman route gave me a way to make a living. The thing is, I don’t go in there to lose, not exactly. But if you upset the ticket sellers, then the promoters won’t use you. So if you want to get rebooked, you have to do enough to make the fight interesting without causing a problem. I could open up, bash him about, maybe catch a couple myself, and I’m still not going to get the decision. So what’s the point? I might as well make things easy.”

Turley’s work is thoughtful and honest. There are times when his recitation of each journeyman’s story is repetitive. And readers have to remind themselves from time to time that there’s nothing noble about a fighter pulling his punches to lose a fight. It’s like a basketball player shaving points.

In the end, Turley acknowledges as much, writing, “In the final analysis, the stories here have not been about heroes. They have been about reality. Losing on purpose for money is not what sport is meant to be about.” But he adds in closing, “Journeymen didn’t create the system. They just operate within it.”