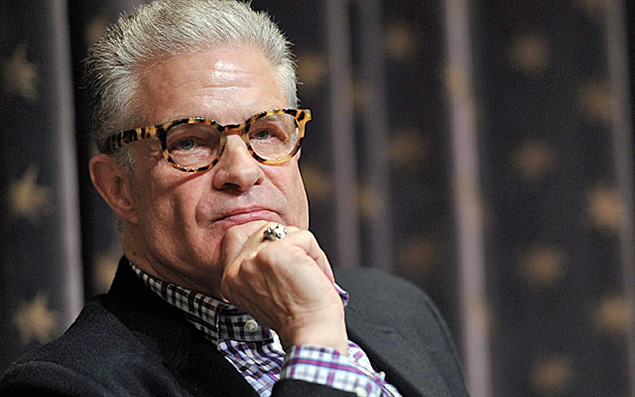

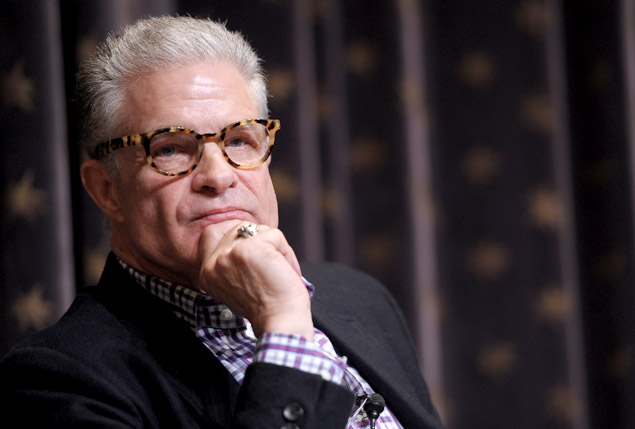

Hall of Fame: Jim Lampley, the Voice of Boxing

HALL OF FAME: CLASS OF 2015

Photo by Michael Loccisano/Getty Images

THE VOICE OF BOXING

JIM LAMPLEY HAS PUT WORDS TO MANY OF THE SPORT’S GREATEST MOMENTS

Jim Lampley was raised on March Madness. As a student broadcaster at North Carolina, he watched NC State break UCLA’s national championship streak in 1974.

Even today, a season-ending misstep by the Tar Heels will bring forth a rant from Lampley equal to the ones he delivers when the referee doesn’t stop a fight in time.

But he encountered Madness at its most unhinged on March 13, 1999, in the middle of Madison Square Garden.

Lennox Lewis met Evander Holyfield that night. Both had brought to the ring every heavyweight belt in existence. At last, boxing’s glory division would be back on the front sports page.

The fight itself was simple enough. Lewis was bigger, more dangerous, better. The only thing he didn’t do was knock out Holyfield, although the fight was close to a stoppage a couple of times.

“Everybody wanted a unified heavyweight champion. Now we had one,” Lampley said.

“And Michael Buffer came into the ring …”

Somehow, Buffer kept a straight face as he read the judges’ cards. Eugenia Williams gave the fight to Holyfield. Larry O’Connell called it a draw. And it was ruled a draw.

New Yorkers who had seen everything looked beseechingly at the ceiling. Lampley looked straight ahead.

New Yorkers who had seen everything looked beseechingly at the ceiling. Lampley looked straight ahead.

“Buffer had barely gotten it out of his mouth,” Lampley said. “Ross Greenburg, our producer at the time, was in my earphones.”

“Go for it,” Greenburg said.

Immediately, Lampley cried, “Out of the cesspool of boxing comes the latest unmistakable stench …”

Only boxing. Only HBO. And only Lampley, 66, who finally joins the International Boxing Hall of Fame this year.

He is this century’s singular boxing voice, a child of the sport who has never tried to bridle his passion or dilute his opinion. He is working for a cable network that is tied closely to boxing but isn’t afraid to administer tough love.

He is also a fully prepared broadcaster whose ability to process information and bring it into complete sentences is an unteachable skill.

“Jim was always our quarterback,” said Larry Merchant, who flanked Lampley at ringside along with a procession of distinguished analysts like Ray Leonard, Emanuel Steward and George Foreman.

“It was amazing how he could come up with the most obscure facts and memories. He’s one of those people who just remembers everything. I was merely along for the ride.”

Lampley’s devotion to boxing branches out into his accompanying HBO show, “The Fight Game.” But it was hatched long ago and far away, and only brought to life by a series of fortunate events.

BLOOD AND SWEAT

Lampley grew up in Hendersonville, North Carolina. His father, Jim, had been a fighter pilot but he died of cancer when he was 35 and young Jim was 5.

Peggy Lampley did not want her son to forget his paternal ties. She made sure he did the things he would have done with his dad.

“One night she sat me down in front of the TV,” Lampley said. “It was the ‘Friday Night Fights.’ That night Ray Robinson fought Bobo Olson. It became a ritual. I think she actually may have had a crush on Ray Robinson.

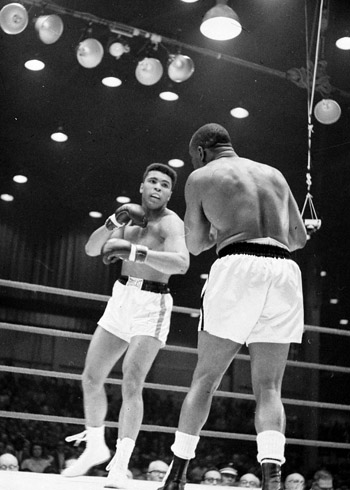

“I began to identify the guys I liked, like Dick Tiger, and the guys I didn’t like, like Gene Fullmer. And then came the Rome Olympics and the fighter with a slave name. Cassius Marcellus Clay.”

Clay either captivated or repelled. No other athlete had been his own bullhorn, had openly ridiculed his older, well-respected opponents and then beaten them. It was professional wrestling gone mainstream. But you couldn’t see the twinkle in Clay’s eye when you read his garish boasts in the newspaper. Lampley somehow could.

They go in the ring, almost naked, with no teammates, no place to hide … You see the layers get peeled off. And you see boxers from very poor backgrounds, from all over the world, fulfilling their dreams. There are no filters. It’s very real.

He also was growing up in the South, where change had to brave billy clubs and attack dogs before it became a way of life.

“I felt I was on the right side of the racial issue in a place where not everybody was,” Lampley said. “[Clay] was the one who took on the establishment.”

Peggy and Jim moved to Miami. Coincidentally, that’s where Clay trained with Angelo Dundee. In 1964 Clay got a chance to meet champion Sonny Liston, who had destroyed Floyd Patterson twice. To Lampley, this was a harmonic convergence.

Peggy and Jim moved to Miami. Coincidentally, that’s where Clay trained with Angelo Dundee. In 1964 Clay got a chance to meet champion Sonny Liston, who had destroyed Floyd Patterson twice. To Lampley, this was a harmonic convergence.

“I saved my money from the lawns I mowed and the other jobs I did because I knew what was coming,” he said. “On the night of that fight, I got my mom to take me down to the Convention Center in Miami Beach and drop me off. Then she would drive around and pick me up. I was 14.

“I was one of the very few there who was rooting for Clay, as if Liston, this ex-con, was the good guy. And I had a pretty good seat. When Clay’s glove cut Liston right below the eye, I could see the blood. I could see the sweat. I think the ticket was $100 or $150. The reason I don’t know is that I don’t still have the ticket. That was my only regret.”

Clay humiliated Liston, who did not leave his stool when the sixth round ended. Peggy picked up Jim and later that night Jim climbed to the roof of the house and yelled to the neighborhood and to the nation beyond, “We shocked the world!”

THE TRAIL OF TYSON

At North Carolina, Lampley was young and polished and self-assured. And ABC Sports liked all of the above. He became a college football sideline reporter, then moved to Major League Baseball and soon achieved the top goal of any ambitious TV journalist – unavoidability. Lampley worked at ABC, CBS and NBC, gave out the Vince Lombardi Trophy, and was a major presence in 14 different Olympics, both summer and winter.

But no boxing. ABC was the only network that was interested and ABC was Howard Cosell, at least in Cosell’s mind.

“It’s the one thing I wanted to do,” Lampley said, “but if he ever knew anyone else wanted to horn in on a piece of action, there would be hell to pay. He did the fights by himself.”

Finally, Cosell sat through 15 stupefying rounds between Larry Holmes and Randall “Tex” Cobb in 1982 and could stand no more. ABC moved Lampley to boxing, although he suspected the real motive was exile. “Dennis Swanson ran the department and he wanted me out,” he said. “I think he felt boxing was an obscure place to put me.”

It was nothing of the sort. A teenager named Mike Tyson was flattening everything that moved in upstate New York. Add the wisdom of trainer Cus D’Amato and the intellect of manager Jim Jacobs, and Team Tyson quickly became the best story in sports.

Lampley was there, in Glen Falls and Troy in upstate New York and the other places Tyson touched down. His analyst was Alex Wallau, a boxing expert who was fighting throat cancer.

“Alex and I lived near each other in Manhattan,” Lampley said. “I’d go over to his apartment and we’d watch boxing videos. He’d tell me to look at the foot position when a southpaw fought a right-hander, how a guy would clinch and hit a guy in the ribs when the ref was on the other side. He taught me a whole new way to look at boxing.”

ABC also had rights to Top Rank fighters like Holyfield and Pernell Whitaker. But when Lampley’s contract ran out, he had a specific chair in mind. He told his agent, Arthur Kaminsky, “I want to do fights on HBO.” His first one was Tyson vs Tony Tubbs, in 1988. Two years later he was in Tokyo when Tyson ran afoul of Buster Douglas.

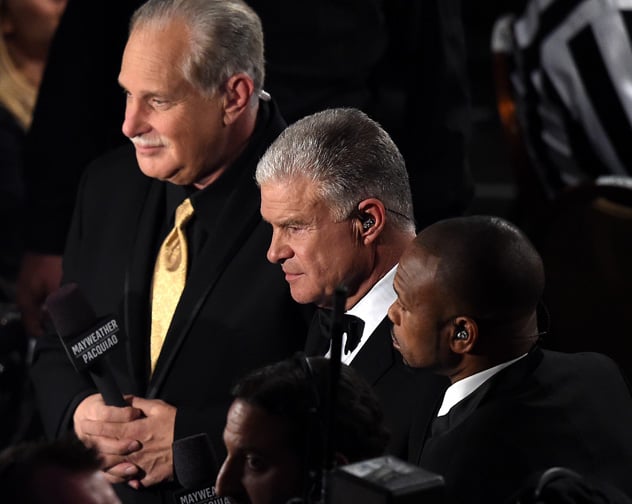

Photo by Harry How/Getty Images

“Jim’s reporting instincts came through that night,” Merchant said. “It’s a simple thing but when it happened, he said, ‘Mike Tyson has been knocked out.’ Because that was the story. The story wasn’t that Buster Douglas was the new champ. It was that Mike Tyson had been knocked out.”

The Lampley-Foreman-Merchant show wasn’t quite as rollicking as the original “Monday Night Football” cast but it had its moments. Merchant, the longtime sports columnist, and Foreman both held tightly to their opinions and Lampley would cast the deciding vote.

“Shane Mosley got the decision the second time he fought Oscar De La Hoya,” Lampley said. “We were all talking to the camera afterward. None of us thought Mosley won the fight. But George started saying (promoter) Bob Arum had it fixed. Larry and I were having a hard time with the theory that Bob would go against his own fighter, which, in this case, was De La Hoya.”

Lampley now works with Max Kellerman and former champ Roy Jones Jr. They don’t disagree as sharply and Lampley appreciates the way they immerse themselves in the action.

“Roy is as perceptive as anyone I’ve seen,” Lampley said. “Often he’ll say things will happen before they do. We were doing Terence Crawford’s fight against Yuriorkis Gamboa and Crawford went southpaw. Roy said he would start getting hit and he was right. Of course, he also won the fight.”

Lampley saw Foreman shock Michael Moorer to become champion again, at 45. He saw Juan Manuel Marquez club Manny Pacquiao to the canvas, where Pacquiao stayed, face down, for several chilling seconds. He has seen death in the ring, including the night when Jimmy Garcia died at the hands of Gabriel Ruelas, but he also has seen life at its most vivid and elemental. It all goes back to a black-and-white TV set.

“They go in the ring, almost naked, with no teammates, no place to hide,” Lampley said. “You see the layers get peeled off. And you see boxers from very poor backgrounds, from all over the world, fulfilling their dreams. There are no filters. It’s very real.”

It can be a cesspool or a cathedral. For nearly 30 years, the same resounding voice has navigated us through both.