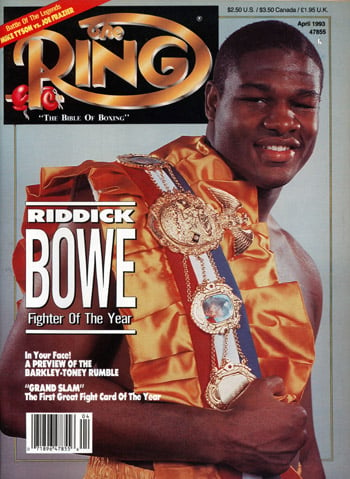

Hall of Fame: Riddick Bowe’s legacy will forever include ‘what if?’

HALL OF FAME: CLASS OF 2015

Photo by Holly Stein/Getty Images

NAGGING QUESTIONS

RIDDICK BOWE’S LEGACY WILL FOREVER INCLUDE ‘WHAT IF?’

As a young amateur boxer, Riddick Bowe aspired to become the second coming of Muhammad Ali. He didn’t quite make it, as is the case with any number of Ali imitators who attempted to duplicate the original. Instead, the two-time former heavyweight champion became the first coming of Riddick Bowe, which in some people’s eyes is very much like the second coming of Ingemar Johansson. That’s why “Big Daddy’s” election to the International Boxing Hall of Fame’s Class of 2015 has sparked such spirited debate.

Enshrinees into any sport’s hall of fame can be divided into two categories. There are slam-dunk selections whose credentials are so impeccable that nary a voice is ever raised in dissent. But sports halls are not universally populated with Babe Ruths, Johnny Unitases, Bill Russells and, in the case of the IBHOF, Alis and Sugar Ray Robinsons. Thus the age-old question: Is a particular nominee to boxing’s highest individual honor indisputably worthy of such designation?

Photo by Holly Stein/Getty Images

Bowe, former lightweight champion Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini and former featherweight titlist “Prince” Naseem Hamed comprise the first IBHOF class in the “Modern” category since the adjustment of the eligibility period. Each will be inducted on June 14 in Canastota, New York, with question marks attached. But, perhaps even more so than those other newly minted Hall of Famers, Bowe has sparked the kind of barstool and media-fueled objections not raised for any heavyweight candidate since the late Johansson gained admittance to the club in 2002.

Like Johansson, who won a silver medal in the 1952 Helsinki Games, Bowe has an Olympic pedigree, having taken silver in the super heavyweight division in Seoul in 1988. Like Johansson, best known for his three-fight series with Floyd Patterson, Bowe’s primary distinction as a professional is his epic trilogy with Evander Holyfield. The difference between them in that respect is Johansson was 1-2 against Patterson while Bowe won two out of three against Holyfield.

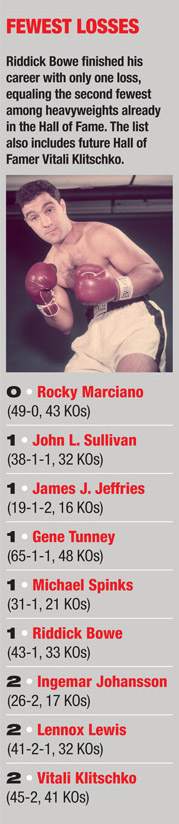

Like Johansson, whose 26-2 pro career (with 17 knockout victories) includes few big-name opponents with the exception of Patterson and Eddie Machen, Bowe’s 43-1 (33 KOs) mark is somewhat bereft of matchups with the finest heavyweights of his era. Yes, he did go to hell and back with Holyfield three times but his other title bouts during his two championship reigns hardly reads like a Who’s Who of the division: Jorge Luis Gonzalez, Herbie Hide, Jesse Ferguson and Michael Dokes. Yes, Bowe did face credible opponents in non-title matchups – Andrew Golota (twice), Bruce Seldon, Pierre Coetzer, Buster Mathis Jr., Larry Donald, Tony Tubbs, Tyrell Biggs and Bert Cooper – but, considering the talent-enriched period in which he competed, where is the name of Lennox Lewis? Mike Tyson? Not to mention Michael Moorer, George Foreman, Larry Holmes, Ray Mercer, Buster Douglas, Tommy Morrison, Razor Ruddock and David Tua.

I really wanted to fight Lennox. I wanted to fight him so bad I could taste it. I wanted to fight him more than anyone.

Bowe, now 47, acknowledges that his enshrinement into the IBHOF has been met with some resistance. But he said it isn’t his fault that his path to Canastota detoured around some of the more dangerous intersections. He said he “desperately” wanted to test himself as a pro against Lewis, who, representing Canada, stopped him in two rounds in the gold-medal bout in Seoul. Bowe insists he was just as eager to mix it up with homeboy Tyson, who came from the same gritty, crime-infested Brownsville neighborhood in Brooklyn, New York, that he did but was steered away from those and other potential career-defining bouts by his manager, Rock Newman. Newman, according to Bowe, was in “total control” of any and all decisions regarding who and when he fought.

“I really don’t have any regrets,” Bowe said. “The fact that I fought Evander three times pretty much made up for everything else. I think those other guys (Lewis and Tyson) realize that they couldn’t have done anything better than I did when I fought Holyfield. They couldn’t even have done it as good. When they saw what I did with Holyfield, they had to know they couldn’t have beat me anyhow.”

“I really don’t have any regrets,” Bowe said. “The fact that I fought Evander three times pretty much made up for everything else. I think those other guys (Lewis and Tyson) realize that they couldn’t have done anything better than I did when I fought Holyfield. They couldn’t even have done it as good. When they saw what I did with Holyfield, they had to know they couldn’t have beat me anyhow.”

So if Bowe is confident that he would have had success against the two most obvious omissions from his resume, why didn’t he just go ahead and fight those guys? Bouts with Lewis and Tyson, perhaps even multiple times, would have significantly added to his net career earnings of $30 million, a tidy sum nonetheless that has all but vanished due to profligate spending and a raft of legal problems that also served to drain his bank account.

“If I could change anything, the No. 1 thing is that I wouldn’t have Rock Newman as my manager,” Bowe said. “I wish I had had people around me who had my best interests at heart, like (Floyd) Mayweather (Jr.) has. I wish I was more into the financial part of the game, that I had paid more attention to what was going on around me. There were meetings and stuff where I needed to be there. I really thought that [Newman] had my back. He didn’t. That made all the difference.”

Newman, who was sued by Bowe and whose relationship with him has turned so frosty as to be non-existent, has contended that some of the signature fights that Bowe might have had didn’t get made because, well, doing business in boxing can be difficult and closing multimillion-dollar deals at the negotiating table isn’t always as easy as an elite fighter hooking off the jab.

“Bowe wanted fame and fortune,” Newman told the Washington Post in 2010, describing his oversight of Bowe’s career as one might the difficulty of dealing with a petulant child. “He wanted to be Muhammad Ali. But he didn’t want to pay the price for it. He could not internalize the process. He hated the process.”

That might explain why Bowe constantly had problems maintaining an optimal fighting weight and so disliked the rigors of training camp. But that should not have been an obstacle to arranging fights that the public wanted to see and that Bowe insists he wanted to participate in.

“When it comes to making big fights, nothing is automatic,” Newman said, comparing Bowe’s circumstances with the long delay in finalizing Mayweather-Manny Pacquiao. “The bridge between wanting to see something and actually seeing it can be steep and long. Sometimes it’s a bridge that leads to nowhere.”

That bridge that never reaches the other side, Bowe said, began with the injudicious decision to toss his WBC championship belt into a trash can in London (he retained his WBA and IBF titles) after Lewis had won a WBC elimination bout by stopping Ruddock in two rounds in that city on Oct. 31, 1992. The prevailing impression then, and now, is that it was Bowe ducking Lewis, not the other way around.

“That was Rock Newman’s idea,” Bowe said of the trash-can deposit that so impacted his career and how so many have come to perceive that career. “I wish I never would have done that. I really wanted to fight Lennox. I wanted to fight him so bad I could taste it. I wanted to fight him more than anyone.”

Opinions, of course, will have to suffice when hard evidence is lacking. If there is anyone who has a reasonable claim to knowing what might have happened had Bowe and Lewis ever squared off, it is Holyfield, who spent a lot of time trading leather with both. And the “Real Deal” – past and present – casts his ballot for Bowe.

Opinions, of course, will have to suffice when hard evidence is lacking. If there is anyone who has a reasonable claim to knowing what might have happened had Bowe and Lewis ever squared off, it is Holyfield, who spent a lot of time trading leather with both. And the “Real Deal” – past and present – casts his ballot for Bowe.

Prior to his first scrap with Lewis on March 13, 1999, Holyfield, his three wars with Bowe already in the books, suggested that “Lennox Lewis can’t show me anything that I haven’t already seen from Bowe. Bowe is a bigger, more complete fighter than Lewis. He can fight on the inside and from the outside. Lewis is kind of one-dimensional by comparison.”

Sixteen years later, has Holyfield reversed course on that somewhat daring suggestion? No, he has not. He also believes that Bowe – at least a fit, motivated Bowe – would have been too much for Tyson to handle.

“It’s still the same,” Holyfield said when asked to confirm or deny his original projection of the Lewis-Bowe fight that never happened. “Lennox Lewis is a very strong guy but he just held you when he got on the inside. That’s it. Riddick Bowe, he’d punch you when you got in tight. Lennox would try to hit you with one shot and if he hit you with that shot, he’d try to hit you with another one. But if he missed, he’d grab a hold of you and put all his weight on you. Bowe, to me, was a more complete fighter.

“I also think Bowe would have been too much for Tyson. Lewis, I don’t believe, wanted to fight Tyson when he was younger. I know Lennox was scared of that Tyson.”

Controversial opinions, to be sure, and not shared by everyone. But Kathy Duva, whose Main Events was Lewis’ American promotional company, agrees with the notion that a Bowe-Lewis fight never came to be primarily because of interference from Newman.

“I can’t speak for what Riddick thought but we definitely wanted the (Bowe-Lewis) fight,” she said. “Everybody knew that. We tried and tried and tried to make it happen. Lennox wanted to unify all the titles but Rock just didn’t want to do it, and Bowe literally threw the (WBC) belt in the garbage. I’m sure that was Rock’s idea.

“Rock was impossible. The way we get frustrated now with Richard Schaefer and Al Haymon, that was Rock back then. You couldn’t deal with him.”

Fight fans thus are left to sift through the whys and wherefores of the enigmatic Riddick Bowe. Is the real Bowe the steadfast guy who refused to yield to the lure of drugs and crime in Brownsville and who walked his mother home from her bus stop to protect her from any possible harm and who earned Holyfield’s undying respect where it counted, inside the ropes? Or is the real Bowe the clownish figure who routinely gained 30 or 40 pounds between fights, who lacked the discipline to have the kind of staying power that would have prolonged his prime and who washed out of Marine boot camp after just a week?

He likely is a little bit of both, just as Johansson is an assemblage of seemingly mismatched parts comprising an intriguing whole. But sometimes it is an individual’s inconsistencies that set him apart and form the basis of his legacy, for better or worse.

Renowned strength-and-conditioning coach Mackie Shilstone, whose celebrity client list also included such fighters as Michael Spinks, Roy Jones Jr. and Bernard Hopkins, said he can never forget the time he spent with Bowe.

“Getting Riddick into the condition he needed to be in just became a battle,” Shilstone said. “It almost burned me out. But he also was the funniest guy I ever worked with. When he fought Holyfield the first time, Evander and Tim Hallmark (Holyfield’s conditioning coach) were floored by Bowe’s mobility. They thought he’d be slow and ponderous but he outpunched Holyfield 2-to-1. After the fight, Holyfield even said he thought Bowe wouldn’t have anything left after the eighth round.

“I just hope Riddick finds whatever it is he’s looking for. It always seemed to me he was looking for some alter ego. I think that’s what happened when he went into the Marines. You know that was a form of escapism. He was always trying to escape from, or to, something.”