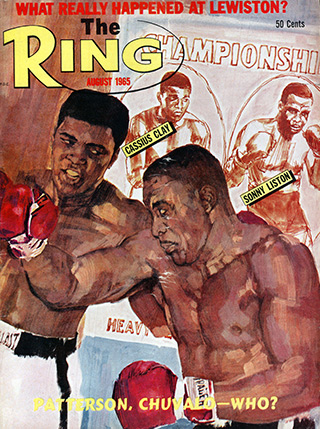

‘Phantom Punch’: The 50-year anniversary of Ali-Liston II

[springboard type=”video” id=”1526929″ player=”ring003″ width=”648″ height=”511″ ]

There was a punch – and it landed.

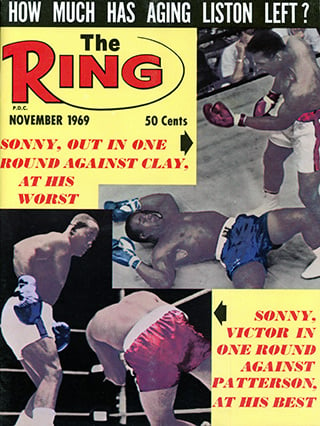

Approximately half way through Round 1 of what is arguably the most controversial heavyweight championship fight in boxing history the challenger, Charles “Sonny” Liston, fell short with a left jab and a right hand counter from Muhammad Ali sent him stumbling forward to the canvas.

Had the fight taken place today there would have been countless angles to analyze but on May 25, 1965, in Lewiston, Maine, there were only a handful of operational cameras and not one captured the blow perfectly. Thus, after former heavyweight champion Jersey Joe Walcott (who refereed the bout) botched the count, and former Ring magazine editor Nat Fleischer notoriously informed the timekeeper the fight was over, the legend of a “Phantom Punch” was born.

Ali reigned supreme, officially, at 2:12 of Round 1 and the unimaginable result was both front and back page news around the world. Liston – toughest man alive, former leg breaker, never stopped – knocked out by a single, and practically invisible, punch? Nobody should have been surprised because controversy had always surrounded the Ali-Liston rivalry.

Ali reigned supreme, officially, at 2:12 of Round 1 and the unimaginable result was both front and back page news around the world. Liston – toughest man alive, former leg breaker, never stopped – knocked out by a single, and practically invisible, punch? Nobody should have been surprised because controversy had always surrounded the Ali-Liston rivalry.

On February 25, 1964, Ali, then Cassius Clay, upset Liston in six rounds to win the heavyweight championship of the world. That night, Clay exited the ring at the Miami Beach Convention Hall without a scratch and a throng of worldwide media sat with their mouths agape. At the time it was pegged by many scribes as the biggest upset in boxing history.

“The bear couldn’t hurt me. The bear couldn’t get a good lick on me,” Clay beamed at the post-fight press conference.

However, his coronation was not without incident. In the fifth round, Clay survived the entire three minute session with an unknown substance affecting his vision. Liston swung, and swung, and swung, and missed, and missed, and missed. When he stayed on his stool the excuse was that he’d pulled his left shoulder out of the socket. One could believe it.

The biggest prize in sport belonged to Cassius Clay and this new status gave him added confidence when he officially announced what a large percentage of the American public already knew about – his affiliation with the Nation of Islam. Clay had been attending religious meetings for years and, with good reason, kept his beliefs private. Only days prior to the first Liston bout, news of his conversion leaked and the fight was almost called off due to an undeniable mix of xenophobia and racial prejudice.

None of that mattered now. Clay was in the driving seat and he knew it. At a hastily arranged press conference, held days into his title reign, he said, “I don’t have to be what you want me to be. I’m free to be what I want to be and think what I want to think.”

Only weeks after his victory, Cassius Clay was given the name Muhammad Ali by his religious leader Elijah Muhammad and two months later, the new champion ventured to Africa. For the first time he was exposed to life as an iconic figure and although these trips became customary in later years, this one was special. He met heads of state, mixed with tens of thousands of people who idolized him and, in essence, got a sense of himself.

Was Ali perfect? Far from it and, although scores of rose-tinted glasses may shatter, that is demonstrable. During his early fighting years Ali was enormously controversial in areas involving race and religion and the heat of today’s media microscope would surely have consumed him. With that said, at his zenith, Ali was a simply stunning paradox and the good he could manifest, with his mere presence, cannot be understated. “The Greatest” was an incredible force of nature, both inside and outside the ring.

As for Sonny Liston, he was back to work in Denver, Colorado, whipping himself into proper fighting trim for the first time in years. Now acutely aware of Ali’s phenomenal ability, the former champion was determined to even the score and sparring partners were being butchered for fun. The feeling was this was now the same destructive force that had scored back-to-back first round knockouts of former champion Floyd Patterson.

Ali-Liston II was originally scheduled for Monday, November 16, 1964, at the Boston Gardens but fate had other ideas. Three days prior to the bout, Ali was in his hotel room when he suddenly felt unwell and experienced bouts of vomiting. He was taken to hospital where doctors performed an emergency operation to repair a hernia.

The bout was ultimately rescheduled for May 25, 1965, but Liston had lost his mojo whereas Ali was approaching his physical peak. The event was also losing box office appeal. Ali’s religious views juxtaposed alongside Liston’s mob connections were making the return bout a near impossible sell. This long awaited rematch made its way to St. Dominic’s Arena, a hockey rink, which held fewer than 5,000 fans, and it was only half full when the fighters made their way to the ring.

On fight night “The Greatest” was introduced as Muhammad Ali for the very first time by ring announcer Johnny Addie. He oozed confidence throughout the introductions whereas Liston appeared sullen and almost disinterested by the whole occasion. We’ll never really know the reason why he made no serious attempt to get up from the sharp shot which felled him, but he would never fight for the title again.

Between July 1966 and September 1969, Liston won fourteen fights, thirteen of them by knockout. The ex-champion was actually very close to a championship fight with “Smokin” Joe Frazier” when his plans were derailed by Leotis Martin, who knocked him cold with a massive right hand in Las Vegas. Martin’s celebrations were short lived. He was forced to retire due to a detached retina, a product of Liston’s pounding jab.

Between July 1966 and September 1969, Liston won fourteen fights, thirteen of them by knockout. The ex-champion was actually very close to a championship fight with “Smokin” Joe Frazier” when his plans were derailed by Leotis Martin, who knocked him cold with a massive right hand in Las Vegas. Martin’s celebrations were short lived. He was forced to retire due to a detached retina, a product of Liston’s pounding jab.

Ali and Liston were chalk and cheese, and so were their respective lives and careers. Ali would go on to become the most recognized figure in all of sports and, at one point, the most recognizable face on earth. Contrast that with Liston who, one year after being flattened by Martin, was found dead at his Las Vegas home. The cause of death remains a source of mystery to this day but heroin, poison and mafia are often associated with the former champion’s demise at the age of forty.

According to a Muhammad Ali autobiography entitled “The Greatest,” which was first published in 1976, Ali and Liston once met in California. It was 1969 and both were applying for State boxing licenses. They would both be turned down. Ali, feeling awkward at being in Liston’s presence, suddenly felt compelled to inform his former rival that Jimmy Ellis had seriously injured his ribs in sparring before their infamous rematch.

“It came into the gym like a hot tip on a horse.” Ali recalled Liston saying. “If I had only believed! Had your ass back in Louisville for good. I could’ve shut your big mouth, once and for all.”

Fat chance. They parted on good terms and said they would see each other again. They never did.

Tom Gray is a member of the British Boxing Writers’ Association and has contributed to various publications. Follow him on Twitter: @Tom_Gray_Boxing