The pride of the Fighting Matthysses – part one

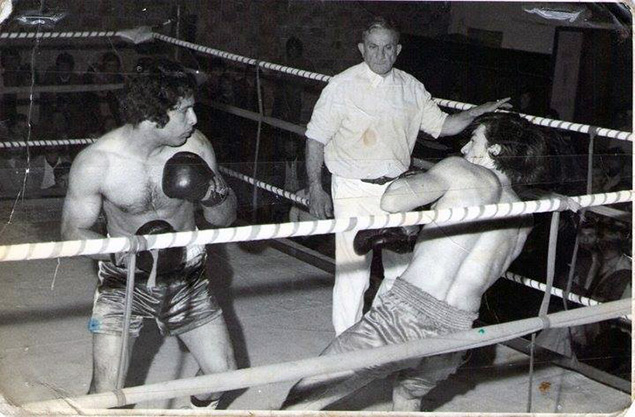

In his heyday, Mario “Cowbird” Matthysse (left) was known for mowing down an opponent or two. Here he is against Eduardo Portela, who he stopped in three rounds in Esperanza, Santa Fe, Argentina in 1979. Photo courtesy of Mario Matthysse.

Latino fighters are expected to have Latino punching power. And Latino looks. And Latino fighting styles. And Latino names.

For the most part, Lucas Matthysse, THE RING’s No. 1-rated junior welterweight, passes every test on this checklist.

His surname, however, is the one thing that sets him apart from the Gonzalezes, Perezes, Chavezes and Lopezes of the Latino boxing world. But he owns the same style and power for which Latino fighters are known for.

And his family history proves to pack quite a wallop as well. At least for the vast majority of his fans who remain oblivious to his personal background.

“Steinbach is German, and Matthysse is French, I think,” says Lucas, when asked about his family names. “I don’t know how the story goes, but I know that’s where we come from”.

That’s a whole lot of surety for a young man who comes from a country where not everyone knows exactly where they came from. Or a country in which people came from so many different places, it is generally impossible for them to respond to the eternal question of “what are you,” try as they may.

It is said around Latin America that “Mexicans descended from the Aztecs, Peruvians descended from the Incas, and Argentines descended from the sailing ships.” And that statement holds true for Matthysse as much as anyone else in this country of 40 million, which held as little as 300,000 inhabitants in 1890 but which ballooned up to more than ten times that many only 20 years later, in 1910. And that was before the end of each of the two World Wars, when hundreds of thousands of refugees, escapees, and just hungry migrants in search of a safe haven (and hopefully a job) made their way to the Land of Silver. The Steinbachs and the Matthysses are two of those families, and Lucas is one of the offspring of that long search for peace and hope.

On Saturday, Lucas will be looking to add a new page to his already illustrious record as a prizefighter when he takes on THE RING’s No. 3-rated junior welterweight Ruslan Provodnikov, and his name will belong to the world. His story, however, will always be linked to a country shaped and built by immigrants. And here it is, as told by the protagonists themselves.

Koppig, als een goede Nederlandse

Mario Matthysse remembers only a few things from his Dutch grandfather.

By the time Mario was a kid, though, the language of his elders was already lost. But just as it is the case with every immigrant, the Matthysses resorted to their original language and customs when it was time to reprimand their kids.

And that’s always the easiest childhood memory to remember.

“My grandfather used to tell me I was ‘stubborn, like a good Netherlander.’ And when I asked him why, he would tell me the story of his family. They came from Holland in the late 1800s, and everyone else was born here,” says Mario.

And by “here” he means a town lost deep in the Argentine lowlands, with a very welcoming name for any weary immigrant: Esperanza (Hope, in Spanish) in the north of the province of Santa Fe.

Now that the family name has started a new trek, Mario can only hope that his old Dutch relatives would be here to hear his own story. In any language.

“Today, the name of Matthysse is going around the world, and we all feel proud for Lucas. He earned every bit of it.”

After being and raised in Esperanza, Mario “Cowbird” Matthysse (who would end his career in 1989 with a record of 33-12-6, 16 KOs according to BoxRec) and his wife Doris moved to the city of Trelew, in the southern province of Chubut, where Lucas was born. They had another son (Walter, a former contender who had a brief career in the United States under Golden Boy Promotions) and two daughters (Soledad, also a boxer, and Jenny) before moving South in search of better prospects. Mario still lives there, where he is a government employee. But that job allows him plenty of time to train his daughter, currently a female champ in her own right, and to reminisce about Lucas’ beginnings.

“In 1995 or ’96, Walter was already fighting, and Lucas came into the gym. Lucas started to hit the bag like it was a game, and you could already see he had a lot of promise. He was quieter, more thoughtful, and more willing to learn the game of boxing. Walter was much more aggressive because he was a puncher, and he had a completely different style,” says Mario.

But around that time, the Matthysses divorced, and Doris moved back into her old hometown up north. Lucas was torn between his two parents, and he ended up choosing what any other teenager in despair would choose.

He chose Esperanza.

“They came and went to Esperanza, until a friend of mine by the name of Keller (in a neighboring town called Vera) took him under his wing. He became more polished then. I went there to help out a couple of times, but he stayed there and started his career,” said Mario.

Lucas would remain there for a couple of very intense years, living in Keller’s home along with his kids and other amateur boxers, and helping out in the family’s grocery store, working his way towards an 18-fight winning streak capped by an Argentine amateur championship – and the chance to go into the Olympic training facility in Buenos Aires.

“He went to the CENARD (a government-run institute for high-performing athletes), where he had the most important part of his career. He learned a lot there, and that’s where he got the discipline he has now,” said Mario, who then grew accustomed to seeing Lucas fighting in places such as Cuba, Brazil, Peru, Chile and other countries.

Discipline was not amiss in the Matthysse gym in Trelew, but apparently Lucas was determined to find his own discipline, and to plot his own path towards glory.

“(Lucas) always asked his dad to come to the gym with him and train him, but his dad didn’t do that”, said Doris, about the understandably stormy father-son relationship marked by the stubbornness of their ancestors. “His dad wanted a perfect fighter, and nobody is perfect, and much less when you’re 14 years old. His dad would reprimand him, and Lucas would leave the gym.”

Leaving the family gym, however, had a positive impact on Lucas, who then took a workmanlike approach that is still his trademark.

“Walter sometimes didn’t understand some things, and he always wanted to get the KO as soon as possible. Lucas has the advantage of having a great predisposition to learn, and he was able to learn from a lot of different people,” said Mario.

Today, those people include his trainer and former welterweight fringe contender Luis “Cuty” Barrera, and a solid team of professionals like Eduardo Leguizamon, Mario Arano and Matias Erbin. But Lucas’s memories probably include a few teachings that, just like the distant echoes of his great-granddad in his father’s head, are still lodged in a deep place in his mind.

“I saw him fight, but I don’t remember much,” said Lucas, when asked about what he felt when he saw his father up in the ring. “When he fought (former middleweight world champion Jorge) ‘Locomotora’ Castro, I went to see him, but I can barely remember. I used to follow him to the gym as a toddler, I remember that.”

His father has his own memories of seeing his son up in the ring, and they are all good memories.

“He grew a lot after his defeats to (Zab) Judah and (Devon) Alexander, and learned a lot. He learned to combine boxing technique with aggressiveness. And he’s getting the results we see now. He added a lot of accuracy also, and when he goes for the kill he gets the KO.”

For a father as stubbornly demanding as Mario, that’s quite a compliment.

One can only wonder if Lucas’ mom would agree on this line of thought.

Mamma said she’ll knock you out

Doris Steinbach gets her hand raised after her only boxing outing. Photo courtesy of Walter Matthysse

Mothers are the first ones who frown upon the idea of seeing their kids getting hit in the head for a living.

Some cannot accept it. Some others can barely tolerate it. Very few of them understand them. And only a select few encourage them.

And then there’s Doris Steinbach.

“More than anything, it was all about curiosity,” said Doris, mother of Lucas, when asked about the one amateur fight in which she engaged, some 15 years ago. “And once I got up there, it was fantastic. It is not easy being up there, but it was a great experience.”

Doris’ curiosity about approaching boxing as a protagonist was surely spawned by breathing boxing every day of her life. That’s what happens when your brother (light-heavyweight Miguel Angel Steinbach) is a fighter, and then you marry another fighter and have four kids, three of whom become fighters themselves.

That’s when getting in the ring, as optional as it may be, becomes a motive for “curiosity”. And soon thereafter, it turns into a family rite of passage.

“I used to go to the boxing gym just to be in shape, because I like it and I continue doing it today”, says Doris about her daring but short-lived boxing experience. “There was a provincial championship in Trelew (Chubut, hometown of the Matthysses), they asked me if I wanted to fight, and I said no. I told Lucas, and he didn’t want me to do it. So I asked my other son, Walter, if he would be in my corner. I told him ‘I’ll do it only if you’re in my corner.’ And I did it. It was only one fight because there were no more opponents. I was 40 and my opponent was 20. It was a good fight, and a beautiful experience. I woke up shaking like a leaf the next day, when I realized what I had done.”

Doris, who is now retired as an unbeaten female amateur boxing champion with a magnificent record of 1-0, finally understood what her sons went through when they got in the ring. And she is convinced that her example has kept her kids in the right path as well.

“I believe Lucas has seen the fighter in me,” says Doris. “I am an independent mom and I always struggled to raise them. Lucas is the one that looks up to me, always. And he always lets me know that. That was always my teaching, that you have to move forward in life all the time.”

Arguably, Lucas has heeded Doris’ advice. His career has moved forward in giant strides since early 2010, when he dispatched former champ Vivian Harris in four rounds and followed up with a string of eye-catching performances. And Lucas is the first one to admit that he felt the presence of his mother in his fights.

“She was always around my uncle, and then she accompanied my dad, and then she was with Walter, and me, and Soledad,” says Lucas, in reference to her sister, a fighter herself and married to a fighter (Mario Narvaez, brother of former two-division champ Omar Narvaez). “She wanted to know, she was intrigued. And well, she got in the ring, and it’s great. At first I was angry because my brothers made my mom fight, but then I saw the pictures and I almost die laughing. She wanted to feel what we feel, the same rush.”

Today, Doris gets her kicks from a different rush. Like watching her son on the cover of THE RING magazine, as only the third Argentine to ever make it there (at least by themselves), along with Carlos Monzon and Sergio Martinez.

“It was fantastic. I was with Lucas when he received the copy of THE RING, and we all felt the goosebumps. I felt a lot of pride”.

But pride was not the only feeling that Lucas imposed on her. When she divorced Lucas’ father and moved back to her old town in northern Argentina, she felt the pain of detachment from her sons, and then the uncertainty of whether they would be by her side or not.

But to say that toughness runs in the family feels like quite an understatement. And so does the ability to start all over in a new country and with a new family.

Although the dates and details are lost in Doris’ mind, her family’s migration from Germany coincides with the large migration of the Germans of the Volga, who were ethnic Germans displaced into Russia in the late 1700s. During WWII, the Wolgadeutsche were considered too Russian to be brought back to their motherland, and too German to remain in their adopted homeland. Those who fled mass murder and concentration camps made their way to the West, and a great many of them settled in the Argentine pampas, so similar to the Russian steppe that they had farmed for a century. Soon enough, the Steinbachs found their way into a town that felt just right for them, especially in its name: La Paz (The Peace). They would later cross the Paran├í river to settle in Esperanza, surrounded by other colonies and towns inhabited by Northern European settlers (not far away from where American-Danish actor Viggo Mortessen spent a significant part of his childhood in Chaco).

After a trek as tough as her folks’ escape to the New World, following her son anywhere and supporting him in his search for his dream was a minor task for Doris.

“I was always there for him. He trained in Vera, in Rafaela, he worked at a grocery store. He always tried to do his own thing,” said Doris.

Sometimes, being there for him included things like pushing him into the deeper end of the pool when even Lucas himself was not sure he was up for a swim.

“We went to a fight card, and one of the fights had been cancelled. But then Lucas walked in, and they asked him if he wanted to fight. But Lucas said ‘mom, this guy is a man, he has hair all over him.’ And Lucas was just 16. So they made him fight under another name. He went up and got a KO.”

And even in that unusual occasion in which Lucas was unable to defend his family name, he still managed to let the world know that a Doris’ little boy was the one who had his hand raised at the end of the bout.

“They announced his name as Jose Acebal, even though he had ‘Lucas’ tattooed on his chest, but nobody noticed,” laughs Doris, in hindsight.

Jumping into the ring on short notice is nothing new for the Matthysses, even for the ladies. And you don’t even have to be a Matthysse or a Steinbach to feel the call.

A coal miner’s wife would seriously hesitate to take her husband’s place in the mineshaft if they were running low on cash, but the Matthysses are a completely different breed.

“We were starving back then,” says Walter, Lucas’ older brother, when telling the story of his spouse’s unlikely transformation into a reluctant prizefighter. “My wife was training with my mom in the neighborhood gym, just to stay in shape. She came with me when I went to look for a fight, but they had nothing for me. There was a fight available for a woman, though, and she took it.”

And that is how a young Yanina Bianchettin was able to put food on the table for two weeks on her $70 payday for four rounds worth of boxing action. Not to be undone by her mother-in-law, she had one more fight before retiring, putting her record at 2-0. And later in life, she would become the mother of Nerina, Milena and Ezequiel, the latter being now trained by Robert Garcia in Oxnard after a very promising amateur career.

Another lady in the family took her calling a little bit further. Soledad Matthysse (12-7-1, 1 KO) is a tough contender with a deceptive record who has only lost against former or current champs, and who may be approaching her best moment at the age of 34.

“I am always with her and I help her out, but she always took on tough opponents like (Marcela) Acu├▒a, (Jackie) Nava. She trains like crazy, but she always gets the toughest opponents,” said Lucas.

Another sister, Jenny, is not involved in boxing. But you can count on the Matthysse ladies to continue the tradition at one point or another in their future.

“Soledad has three daughters,” says Lucas. The two oldest ones, Mili and Sasha, have their gloves and their handwraps already. And one of them wrote on Facebook ‘I woke up today and I feel I am going to become a boxer.’ In a few years, I think she’ll get there.”

With every other woman in the world, that certainty would be unjustified.

But in this family, that otherwise audacious affirmation becomes just an obvious afterthought.

Diego Morilla, a bilingual boxing writer since 1995, is a full member of the Boxing Writers Association of America. He served as boxing writer for ESPNdeportes.com and ESPN.com, and is now a regular contributor to RingTV.com and HBO.com, as well as the resident boxing writer for XNSports.com. Follow him on Twitter @MorillaBoxing