Brayd Smith and John Moralde: Forever linked by tragedy

photo of Brayd Smith from his Facebook page

MANILA, Philippines – John Vincent Moralde sat quietly at a T.G.I. Friday’s restaurant in Metro Manila with a plate of pork in front of him that had barely been touched. The 20-year-old had been in a 10-round fight the night before but didn’t have a mark on his face to show for it.

There’s little cheer in this celebration dinner, with only his promoter, Jim Claude Manangquil, to keep him company. The regional featherweight title belt he had won was left at Manangquil’s apartment down the street. He wore a Smithy’s Gym t-shirt, a hat tip to the man whose life he’ll forever be linked with.

Only the distant gaze in Moralde’s eyes and the sad, empty grin that crawled across his face suggested the violence he had been a part of the night before.

A 10-hour flight away in Toowoomba, Australia, Moralde had won the biggest fight of his life. Like Moralde, Braydon Smith entered Rumours International convention center in his hometown as an unbeaten fighter. At the final bell, Moralde emerged as the only fighter without a loss, winning a clear decision.

The fight was not designed for the light-hitting Filipino to win. He entered the ring the smaller man against the 23-year-old Smith, having weighed just 120 pounds for his previous fight in September and 112 in his pro debut. Moralde had taken the fight on a month’s notice after the original opponent – Egyptian journeyman Mohammed Metualy – had withdrawn due to a managerial dispute.

Moralde had traveled with just his 22-year-old promoter, arriving two days before the fight, and picked up pro fighter Benny Jade Slade in Australia as an assistant.

Back in the Philippines, Moralde and Manangquil had been in communication with contacts in Australia since stepping off the flight at Ninoy Aquino International Airport a couple of hours earlier. He knew that Smith, who had collapsed in the dressing room about 90 minutes after the fight, was in a Brisbane hospital on life support. He also knew more than the general public did; that Brayd Smith was never going to wake up.

“We came there to lose, not to kill someone,” Manangquil finally said, breaking the silence.

* * *

Smith and Moralde came from very different worlds, with the only thing they seemingly had in common being the sport they both loved.

Smith had turned professional in 2011 after a short amateur career highlighted by winning the Australian Golden Gloves. Smith had hoped to represent Australia at the 2012 Olympics but had to withdraw after a fish bone tore a hole in his esophagus. According to the Courier Mail, the hole caused an infection “the size of a sausage,” which had to be treated with eight bottles of antibiotics a day before he was medically cleared.

Brendon (L) and Brayd Smith

His father, Brendon Smith, had created a boxing culture in the quaint city just 80 miles outside of Brisbane. The elder Smith had a number of young amateurs and professionals through the decades, reaching international recognition through South African featherweight November Ntshingila in the mid-90s before breaking through in the late 2000s with two-time interim lightweight champion Michael Katsidis.

“I was more keen for him to make sure he comes through with a good education and play the golf, play the tennis, play the soccer,” Brendon Smith told a local news station early in his son’s career. “Do it all, just have a good time. When he was old enough to make his own decision, then it’s up to him.”

Braydon was one of three boys born to Brendon and Kerri Smith, and was in his fourth and final year of studies for his Bachelor of Law degree at University of Southern Queensland.

“Law and boxing, they balance each other out great,” said Smith, who called boxing a great stress reliever for his studies.

“He was loved by all,” remembers Phil Austin, a boxing official who judged the Moralde fight and two of Smith’s previous bouts. “[He was] a popular lad with a smile and a chat for anyone. He was a firm fan favorite and he had a large following. Throw in humble and with the world at his feet and you had a wonderful young role model.”

His fighting style wasn’t unlike that of Katsidis, whose aggressive, crowding style and big punching power made him a hit in the United States. Smith, too, was a puncher, having accrued 10 knockouts in 12 wins.

Boxing was also a family tradition for Moralde. He never imagined a life for himself outside of it.

One of 8 children born to a housekeeper and a radio technician at a local news station, three of his brothers were standout amateur boxers with two of them turning pro as well. John began boxing at age six, amassing an incredible 300 amateur fights. After graduating high school, he turned pro at age 17, a month after Braydon’s first match.

Originally, the WBA’s vacant Oceania featherweight title was to be contested for. Their secretary, Derek Milham, had given Moralde’s name as a suitable replacement for Metualy, who at 33 was out of his physical prime.

Some time between the opponent switch and fight week, plans for the WBA regional belt were scuttled and the vacant WBC Asian Boxing Council Continental featherweight title was put up for grabs instead.

Any time that two able-bodied men walk into the ring to slug each other with their fists, the possibility for a tragedy is present.

Entering the fight, Brayd Smith knew that his dreams of bringing a world championship to Toowoomba some day hinged on this fight. Moralde was a significant step up for him and a victory would establish him as more than a hometown attraction.

“I’ve made no secret I want to be a world champion and I see this fight as a significant step towards that dream,” Smith said in a release. “I win this fight, I enter the world ratings and from there you never know – you can get a shot at the world champion.”

Moralde and his promoter arrived in Toowoomba on Thursday, March 12 with six pounds of excess weight to shed off. The following day at noon, a final press conference was held where the two boxers posed and met with the media.

Six hours later, a noticeably smaller Smith stepped on the scale and weighed the same as his opponent, 126 pounds.

The air was cool – but not overwhelmingly so – in the mountains of Toowoomba on fight night. It had rained the day before but the sun broke through on Saturday with a light breeze that hinted nothing of what would occur later that night.

About 1700 people packed in to 323 Ruthven Street for what was the Smiths’ ninth show at the venue. The city is small and Brayd Smith was one of its most popular citizens, having been a fixture on local television newscasts since before his pro debut. Many of those in attendance were friends of the family.

Before the fighters took to the ring, a 10-minute documentary on Braydon Smith was shown for the crowd. The father and son spoke of Braydon’s life in and out of the ring, his plans of pursuing the legal profession after the sport.

Brendon Smith also spoke of the dangers of the sport, about how anything can happen inside those ropes.

* * *

“Would you like any drinks?” the waiter asks the party of three. Moralde, a dedicated athlete, only drinks on special occasions and after fights. Moralde declines a beverage, saying he was full from the dinner he barely touched. Two San Miguel Light beers are ordered plus a glass of water.

“We’re supposed to be happy now. We won a title in an international fight that we were supposed to lose,” said Manangquil, whose dreams of fighting were dashed by his mother, a well-to-do tuna scion in General Santos City, out of concern for his safety.

“Now we can’t think of that. We’re sad, we’re stunned. Brayd and Brendon, they took good care of us, his whole family. That’s why it’s so sad. We’re so shocked.”

We came there to lose, not to kill someone.

– Jim Claude Manangquil

Moralde made the biggest purse of his career for this fight, $3,000 USD. He has a four-year-old son and a live-in girlfriend waiting in Davao City on the western coast of the Philippines in the southern region of Mindanao.

“This is a dangerous sport which is why I always try to be careful,” said Moralde, who knew in just a few hours that the life support machine that kept Smith’s heart beating would be switched off.

Moralde is conflicted. He’s saddened by the situation he was a part of, but tries to show a strong face to ease his more expressive promoter.

“What am I supposed to do? I have nothing. I have to keep fighting,” he told his promoter.

* * *

The fight was not televised and this writer was not in attendance. But from the opening bell, sources in attendance said Moralde couldn’t miss his mark. Moralde, though smaller, used Smith’s aggression against him, landing uppercuts at will. Smith remained undeterred, plowing forward as he tried to slow his opponent with body punching.

Smith’s heavy right cross meant that he was always one punch away from being right back in the fight. But that longshot scenario never transpired.

As the fight wore on, Smith’s high cheek bones began to swell. He continued to do his job as a fighter: he fought on.

Smith’s corner and referee Tony Kettlewell had difficult judgment calls to make. Moralde was not a big enough puncher to knock Smith out, but the accumulation of punishment was beginning to tell.

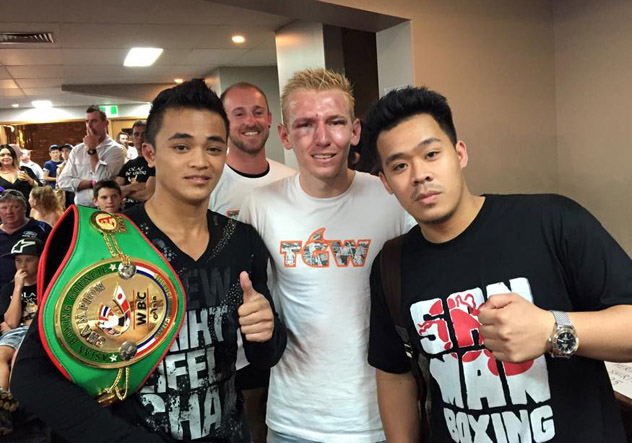

Brayd Smith (L) and John Moralde. (Team Moralde)

“It looked like the kind of fight ÔǪ if you had to give a blueprint for a guy who would collapse,” said a source, who requested not to be named out of sensitivity to the family.

Manangquil says Moralde first wobbled Smith in the eighth round and once again in the ninth. After both rounds he looked across the ring to observe if the fight would be halted. When Smith showed no signs of surrender, Moralde and his corner knew what they needed to do.

Fighting abroad, they knew that they had to continue fighting as hard as they could to ensure victory on the scorecards.

There was no controversy once the verdict was announced. The three Australian judges all scored the fight for the Filipino by the tallies of 99-91, 98-92 and 97-93.

Smith handled his first defeat with class. He posed for photos with Moralde afterward and was particularly chatty. He took a seat and watched as 2012 Australian Olympian Luke Jackson struggled to a 10-round split-decision win over Will Young to win the Australian featherweight title in the main event.

Back in the dressing room, with the adrenaline from his fight subsided, Smith held an ice pack to his head. If he had any indication that something terrible was about to happen, he kept it to himself. This was, after all, the same guy who told doctors treating him for a growth in his esophagus that “there’s worse off in here than me.”

A source who walked past him in the dressing room recalls how pale his complexion had turned – “white as a ghost,” he says. He had seen Smith’s look before, like someone dehydrated and in danger of fainting. “I wasn’t thinking bleeding on the brain.”

Fifteen minutes would pass before the monotony of post-fight business transactions was broken up by an exhortation that signaled the beginning of a nightmare: “Somebody call an ambulance!”

Paramedics arrived minutes later to find Smith slumped to the floor near the chair he had been sitting in. They attached an intravenous drip and rushed him out of the venue to Toowoomba Hospital just six minutes down the road.

There, doctors transferred him by helicopter ambulance to Princess Alexandra Hospital in Brisbane. Smith was placed in a medically induced coma and had emergency surgery to relieve swelling on his brain. He was unresponsive when doctors tried to revive him. The family knew they would have a hard decision to make as they spent their last moments with Brayd at his bedside.

* * *

There is no way to extricate boxing from the dangers inherent to its nature. The goal of the sport is to use your strength, instincts and guile to inflict more damage on your opponent with your fists than you yourself incur, with greater acclaim being awarded to the victor if he can render his opponent helpless or unconscious.

Measures have been taken over the decades to make it safer, if only to appease lawmakers and lobbyists who call for the sport’s abolition. When Duk-Koo Kim perished at the hands of Ray Mancini in a 1982 bout televised across America on ABC Wide World of Sports, 15-round bouts were phased out in favor of a 12-round maximum for world title bouts.

Pre-fight checkups – which some joked consisted of nothing more than holding a mirror under a fighter’s nose to make sure he was breathing – became more sophisticated, with brain scans, electrocardiograms, and eventually blood tests to check for infectious diseases.

Twenty years before the Korean lost his life in a Nevada hospital, the same network televised the third meeting between Emile Griffith and Benny “Kid” Paret at Madison Square Garden in New York City.

It was one of the first glimpses – if not the first – that the American public had gotten of a ring death in the television era, and the sheer brutality of Griffith’s 18 unanswered punches thudding into the head of Paret shocked a nation.

As described in the essay “The Death of Benny Paret” by Norman Mailer:

“Some part of his death reached out to us. One felt it hover in the air. He was still standing in the ropes, trapped as he had been before, he gave some little half-smile of regret, as if he were saying, ‘I didn’t know I was going to die just yet,’ and then, his head leaning back but still erect, his death came to breathe about him.”

Paret’s death inspired a protest song by folk singer Gil Turner, who likened boxing to Roman gladiators fighting to their death, saying, “Benny’s not the first to die down on the canvas floor; Many brave men have swallowed their last breaths while the crowds, they just screamed for more.”

Ring deaths continue to this day, despite measures to prevent them, while the cumulative brain damage many experience – known as pugilistic dementia, or punch drunk syndrome – often takes years to manifest.

John Vincent Moralde (Ryan Songalia)

What am I supposed to do? I have nothing. I have to keep fighting.

– John Vincent Moralde

Smith’s death compelled the Australian Medical Association to re-state their stance recommending for the sport’s abolition in the country. Australian Medical Association Queensland president Shaun Rudd told ABC, “We believe that a so-called sport where two people knock each other in the head as often as you possibly can to win a bout seems rather barbaric.”

There was little to suggest that Smith, who had been medically cleared in October, was at any greater risk than anyone else heading into his final fight. Most of his past fights had ended in early knockouts, with his 2013 bout against Shogo Sakai, where he sustained two black eyes before winning by an eighth-round technical knockout, being the only fight where he took much punishment.

The truth is that there are no routine fights in the sport. Any time that two able-bodied men walk into the ring to slug each other with their fists, the possibility for a tragedy is present.

Observers become desensitized to the violence as fighters often show no indication of the jeopardy they are in. To indicate vulnerability is to embolden your opponent and subject one’s self to more blows.

Only when the fighters are away from the spotlights, the roaring crowds and the television cameras do they let their guards down. Their heads ringing, their facial tissue swelling. A bit of their fighting spirit drained out on the canvas ring.

On the same date as Smith vs Moralde, on the other side of the world in Montreal, Canada, light heavyweight champion Sergey Kovalev pummeled a thoroughly overmatched Jean Pascal around the ring to the dismay of Pascal’s hometown fans.

In the eighth round, Kovalev, who had killed a man named Roman Simakov in Russia in 2011, rained down a number of uncontested right hand punches, causing Pascal’s legs to lose their integrity as he floundered about the ring.

The crowd booed the stoppage, and Pascal the warrior reacted with indignity at the referee’s choice to spare him from superfluous, undefended blows. While news of Smith’s peril was slow to reach the Western hemisphere, many fans derided the stoppage as premature, unsatisfied that the loser had not been beaten to the point of a knockout.

But the other reality is that Smith was a grown man who knew the risks that awaited him in the ring. Did he need to fight to survive, as so many impoverished men do? No, but it was his right to decide whether the risks he was willing to take were worth the benefits he derived from them.

Brayd Smith (center) and John Moralde (L)

None of that is likely to comfort the emotional wounds of Brendon Smith and Manangquil. Two men who have dedicated their lives remain out of the gyms where they have spent a significant chunk of their lives.

Smithy’s Boxing Gym in Toowoomba remains closed until further notice while Manangquil has avoided his Sanman Gym down the street from his home in General Santos City, remaining in his home. After arriving back in GenSan, Moralde took the drive to Davao to spend time with his family and his thoughts.

It’ll be debated for a long time whether Smith should’ve been guided away from the sport, told to focus on being a bar exam top-notcher and making partner at a law firm instead of living off the cheers of his adoring fans.

Only Braydon Smith can say with any certainty. And in an Instagram post dated two years ago to the month, Smith wrote a poem to the ironically dubbed sweet science. The post, which shows him leaning over the ropes, his head covered in sparring headgear and fists encased in boxing gloves, foreshadows how he would die doing what he loved.

Regardless of whether we loved his doing it.

“Because of you (boxing), I can’t eat what I want. I miss my friends, I miss family vacations. I’m sore. I injured myself. I have to constantly train hard even when I’m drained physically and mentally.

“But then again, because of you (boxing) I’m healthier, faster, wiser, strong. I know what I want in life. I’ve seen the world. I’m secure. I’m happier. I’m a better person and I’m the champ!”

Ryan Songalia is the sports editor of Rappler, a member of the Boxing Writers Association of America (BWAA) and a contributor to The Ring magazine. He can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him on Twitter: @RyanSongalia.