Travelin’ Man returns to Atlantic City – Part II

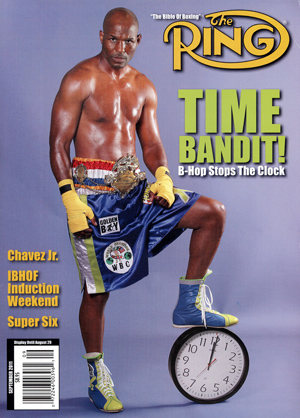

Saturday, Oct. 26: We have seen genius, and its name is Hopkins.

The man formerly known as “The Executioner” now calls himself “The Alien” because of his historic success at an extremely advanced athletic age. By decisioning mandatory challenger Karo Murat, Hopkins added another layer to his already otherworldly accomplishments. Consider:

* Hopkins extended his own record as the oldest man ever to win a major title fight and virtually guaranteed himself the distinction of becoming the first 49-year-old world titlist, for he will surely not fight again until after his birthday on January 15.

* With his 23rd title fight victory he seized sole possession of seventh place on the all-time list. Only Julio Cesar Chavez (31), Joe Louis (26), Dariusz Michalczewski and Ricardo Lopez (25 each), Oscar de la Hoya and Virgil Hill (24 each) are above him.

* Hopkins extended his championship arc to an impressive 18 years 6 months, for he won his first title on April 29, 1995 when he stopped Segundo Mercado in round seven to capture the IBF middleweight belt. George Foreman holds the all-time record with 22 years 5 months, which encompasses his title fight victory over Joe Frazier on January 22, 1973 and Foreman’s relinquishment of his IBF heavyweight title on June 29, 1995 – exactly three months after Hopkins’ initial reign began. That Hopkins achieved his mark without taking a 10-year hiatus as Foreman did makes his deed even more impressive because of the constant wear-and-tear of fighting world-class opposition as well as the hard work required for his never-ending devotion to peak conditioning and dietary discipline. It is difficult to fathom Hopkins breaking Foreman’s mark, for to do so he’ll have to be a major titlist beyond December 2017. Then again, who could have ever thought Hopkins would be able to do what he’s done so far?

* By going the distance with Murat, Hopkins became only the fifth man ever to compete in 300 or more rounds of championship competition. His 301 moves him into a tie with Julio Cesar Chavez and in his next fight he’ll likely zoom past Hilario Zapata (303) into third. After that, if he so chooses, Hopkins will set his sights on Abe Attell (337) and all-time record-holder Emile Griffith (339).

In recent days, more than a few people have used the phrase “living legend” to describe Hopkins. It’s a label with which I heartily agree. He is one of a handful of champions ever to log 20 consecutive successful title defenses, to enjoy a title reign lasting more than 10 years and to be an undisputed champion in the four-belt era. Then throw in everything he has done after age 40: a record of 9-4-1 with one no-contest, a pair of light heavyweight title belts and victories over Antonio Tarver and Kelly Pavlik as a massive underdog. It’s a resume worthy of top 20 status in the all-time pound-for-pound list, an extraordinary accomplishment for a modern-day fighter given the sheer quantitative and qualitative superiority of most fighters rated above him.

Hopkins’ superlative resume is the product of old-school sensibilities that buck new-school attitudes. First, instead of making pit stops in various weight classes just to collect a belt and move on, Hopkins earned his respect the  old-fashioned way – by dominating a single weight class and laying waste to most who dared challenge him. That he ruled at middleweight, the second most historically significant and marketable weight class behind heavyweight, only adds to his credibility in terms of all-time greatness, for he stands tall among confirmed legends such as Stanley Ketchel, Harry Greb, Sugar Ray Robinson, Carlos Monzon and Marvelous Marvin Hagler. It took Hopkins years to gain his proper respect – it wasn’t until he flattened Felix Trinidad in 2001 nearly six-and-a-half years into his IBF tenure – that he began receiving his just due. But once he reached the top of the mountain his unique longevity and iron-willed perseverance earned him an aura unlike any other figure in the sport.

old-fashioned way – by dominating a single weight class and laying waste to most who dared challenge him. That he ruled at middleweight, the second most historically significant and marketable weight class behind heavyweight, only adds to his credibility in terms of all-time greatness, for he stands tall among confirmed legends such as Stanley Ketchel, Harry Greb, Sugar Ray Robinson, Carlos Monzon and Marvelous Marvin Hagler. It took Hopkins years to gain his proper respect – it wasn’t until he flattened Felix Trinidad in 2001 nearly six-and-a-half years into his IBF tenure – that he began receiving his just due. But once he reached the top of the mountain his unique longevity and iron-willed perseverance earned him an aura unlike any other figure in the sport.

Second, Hopkins’ conscious choice to place meticulous attention to detail over flashy physical assets was pivotal to securing his singular place in the sport. Under Bouie Fisher and Naazim Richardson – two of the most knowledgeable trainers to ever live – Hopkins learned and assimilated every old-school technique imaginable. Once Hopkins’ youthful skills peeled away, that supreme knowledge served as an underlying suit of armor that allowed him to thrive at previously unimaginable ages. The final result is a boxing IQ that is off the charts.

Finally, Hopkins also made the old-school choice of staying in fight-ready shape at all times and practicing unparalleled discipline in terms of food intake. This three-pronged blueprint has greatly slowed the inevitable decay all athletes encounter and the result, at least thus far, is that Hopkins still enjoys the best of all worlds – a limitless storehouse of fistic understanding combined with a body still capable of carrying out his brain’s commands. His hands still have above-average speed and his legs are still capable of carrying him where he needs to go. The only sign of obvious decay is his inability to knock out opponents, for he hasn’t scored a stoppage since taking out Oscar de la Hoya more than nine years ago. But even that deficit works for Hopkins because, knowing he’ll likely have to go the distance, Hopkins works himself into enviable cardiovascular shape.

Many of his fights these days have the look of a Ph.D. dissecting a high school student and that fear of being exposed this way is perhaps Hopkins’ greatest weapon. Hopkins’ rivals usually find themselves in a Catch-22. If an opponent chooses to go straight at Hopkins, as Murat did, he’ll get nailed with precise counters. But if he decides to stand at range and look for openings, the fight is all but over because no one this side of Floyd Mayweather Jr. can ever hope to out-think Hopkins.

Another dynamic of Hopkins’ success is his ability to neutralize opponents to the point that they are forced to fight at his pace rather than wage war at theirs. In six encounters with Hopkins Tavoris Cloud, Jean Pascal, Chad Dawson and Kelly Pavlik landed 52 percent fewer punches and threw 36 percent less blows when compared to their recent pre-Hopkins bouts. Although Murat tried to bully Hopkins and force a faster pace, his proactive desire couldn’t be translated to positive action. When Murat fought Nathan Cleverly and Gabriel Campillo, he averaged a combined 74 punches and 24 connects per round for 32.4 percent accuracy. Against Hopkins, Murat threw 40.5 punches per round and landed 12.3 per round, which translates to a 45.3 percent drop-off in punches thrown and a 49 percent decline in total connects.

Once Hopkins got Murat to fight at a more suitable pace he skillfully manipulated the geography for the remainder of the contest. The fight proceeded in three distinctive stages:

Once Hopkins got Murat to fight at a more suitable pace he skillfully manipulated the geography for the remainder of the contest. The fight proceeded in three distinctive stages:

In rounds one through three, Hopkins averaged just 26.3 punches per round and like a snake charmer he lulled Murat into a similarly slow start as he averaged only 28.6, far below the 54 the typical light heavyweight throws. In that span Hopkins led 28-14 in total connects, 13-12 in landed power shots and 13-2 in jab connects.

During rounds four through six Hopkins, now more comfortable in terms of pacing and range, began to turn up the volume as well as the precision. In that nine-minute stretch Hopkins averaged 45.3 punches per round to Murat’s 39.3 and out-landed him 55-32 overall, 16-6 in jabs and 44-26 power. More importantly, Hopkins landed 40.5 percent of his total punches to Murat’s 28.6 and 48.4 percent of his hooks, crosses and uppercuts to Murat’s 32.9 percent.

Finally, rounds seven through 12 saw Hopkins apply all the lessons that were learned in the first six and the results were breathtaking. Hopkins increased his pace to 58.3 punches per round, peaking at 66 in round nine, and out-landed Murat (who averaged 47 per round) 159-101 overall and 125-82 power. Murat’s only bright spot came in the ninth, where his 23 power connects were the most landed on Hopkins in a given round since Roy Jones Jr. landed 25 in round six during their first fight 20 years ago. Even so, Hopkins landed 20 power punches in that session and tied Murat with 27 total connects, the only round in the fight in which Hopkins did not out-land Murat in total punches.

That stretch also produced sounds unfamiliar at most Hopkins fights — thunderous, building-shaking cheers. During several hard-fought exchanges the crowd unleashed its rapturous joy and chanted “B-Hop! B-Hop!” instead of the usual studious silence.

For the fight Hopkins out-landed Murat 247-147 overall, 63-27 jabs and 184-120 power and enjoyed percentage leads of 14 overall (44-30), 15 in jabs (33-18) and 13 in power (49-36). That level of control and accuracy is impressive for a fighter of any age, much less one eleven-and-a-half weeks short of his 49th birthday. One must appreciate the cardiovascular conditioning required for Hopkins to shift upward from 26.3 to 45.3 to 58.3 punches per round while still having enough hand speed to nail a hungry, ambitious 30-year-old at such a high percentage. A final note: Hopkins’ 247 connects is the most he’s registered since landing 260 in his landmark victory over Trinidad 12 years earlier.

As if his physical superiority wasn’t enough, Hopkins also played plenty of mind games that threw Murat off his game. The kiss on the back of Murat’s head was only one source of angst for the challenger, who expressed his frustration by hitting on the break, striking after the bell and, following the final gong, attempting to nail Hopkins with an intentional head butt. The lopsided scores (119-108 twice, 117-110) properly reflected Hopkins’ command on this night.

In past years Archie Moore, Larry Holmes and Azumah Nelson laid claim to the title “professor of boxing” and “The Easton Assassin” punctuated the point by donning a robe and mortarboard for publicity shots. Hopkins has more than earned his spot in that exclusive faculty and, if he has his way, he may get the chance to demonstrate his wiles against another candidate in Mayweather. The possible story line as spelled out by Richard Schaefer: Hopkins, the fighter nearing age 50, against a fighter who aspires to become 50-0.

In past years Archie Moore, Larry Holmes and Azumah Nelson laid claim to the title “professor of boxing” and “The Easton Assassin” punctuated the point by donning a robe and mortarboard for publicity shots. Hopkins has more than earned his spot in that exclusive faculty and, if he has his way, he may get the chance to demonstrate his wiles against another candidate in Mayweather. The possible story line as spelled out by Richard Schaefer: Hopkins, the fighter nearing age 50, against a fighter who aspires to become 50-0.

One has to wonder if Hopkins, who weighed a svelte 172¾, was using the Murat fight as a test run for a possible move down in weight. When I posed this question to Richardson following the post-fight press conference he said his fighter’s weight reflected no special effort to reduce but Hopkins said that the rest of his career will be spent pursuing special challenges that would most likely require him to move down the scale.

A Hopkins fight would make sense to Mayweather only if it can be made for a vacant 160-pound title. Considering the shenanigans the WBC pulled in stripping Sergio Martinez and elevating interim titlist Sebastian Zbik in order to make it easier for favorite son Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. to win a middleweight belt, such a scenario can easily be arranged, especially when potentially big money is involved.

It also would satisfy the oft-used and much criticized Mayweather matchmaking formula that was put on hold when he fought Saul Alvarez. A Hopkins fight for a middleweight title – manufactured or not – would allow Mayweather to enhance his resume while bypassing Gennady Golovkin and Sergio Martinez, who fight on HBO, and Peter Quillin, a Showtime product who has yet to achieve the imprint needed to draw enough money to merit “Money’s” interest.

As for Hopkins, a Mayweather fight makes sense on three levels – money, publicity and history. A fight against the reigning pay-per-view king surely would garner Hopkins an eight-figure paycheck, if not his highest payday ever, and attract the enormous media attention he received when he fought Oscar de la Hoya in 2004. He also would become the second light heavyweight titlist ever to win a 160-pound belt (Thomas Hearns was the first) and, if successful, he would trump Hearns by regaining a middleweight strap nearly a decade after he lost it and by affixing the first loss on Mayweather’s celebrated unblemished record.

But would a Hopkins-Mayweather fight make sense for the fans, or for the sport? And, more importantly, would people buy it?

As of now, no and no. But if the fighters and Golden Boy Promotions are serious about making it happen, the guess here is that it can be made and it can be sold, especially to casual sports fans whose depth of knowledge is limited to the big names Mayweather and Hopkins possess. The hard-core fans and media may well rebel and recoil but if enough casual fans are drawn in the financial impact will be minimal.

If Hopkins’ next fight was staged at a 166-pound catchweight against a credible super middleweight opponent and if he performs well, then he could sell the idea that he could still function at a lower weight. And if Mayweather is sold on the idea of persuading the public that it’s a matter of bigger versus smaller instead of younger versus older, he has the tools to cast the proper verbal spells. After all, wasn’t he on “Dancing With the Stars” and Wrestlemania? Plus, the pre-fight jabber will be something to behold.

Even with the arguments presented here, the odds of Mayweather-Hopkins actually happening are virtually nil. It just seems too freakish a prospect to actually become reality. But then again, Hopkins had promised to retire upon his 40th birthday and now look where he is.

*

Some notes about the undercard fights:

* I’m not sure how two of the three judges could credibly turn in 90-80 and 89-81 scorecards for the Peter Quillin-Gabriel Rosado WBO middleweight title fight. Aside from the second round, in which Quillin scored a flash knockdown, many rounds were tense, low-output affairs that could be interpreted multiple ways. While Quillin earned an early lead, the middle rounds saw Rosado turn up the heat and find the range with several solid right hands. By round 10 it was clear Rosado was coming on and an intriguing finish was at hand.

At the time of the stoppage Quillin led Rosado 88-80 in total connects and 29-18 in landed jabs but Rosado held a 62-59 edge in landed power shots. According to the round-by-round statistics, the widest margin either fighter enjoyed in terms of landed punches was four by Quillin in round nine (10-6) and in rounds four through seven Rosado out-landed Quillin three times, albeit by three, one and two punches. Because of the nip-and-tuck nature of the contest, it’s hard to imagine such lopsided final scorecards, though Quillin did out-land Rosado in six of the nine completed rounds, a stat that gives credence to Ron McNair’s 87-83 scorecard.

At the time of the stoppage Quillin led Rosado 88-80 in total connects and 29-18 in landed jabs but Rosado held a 62-59 edge in landed power shots. According to the round-by-round statistics, the widest margin either fighter enjoyed in terms of landed punches was four by Quillin in round nine (10-6) and in rounds four through seven Rosado out-landed Quillin three times, albeit by three, one and two punches. Because of the nip-and-tuck nature of the contest, it’s hard to imagine such lopsided final scorecards, though Quillin did out-land Rosado in six of the nine completed rounds, a stat that gives credence to Ron McNair’s 87-83 scorecard.

That said, I have no argument with the way the fight was stopped. From my ringside position the long cut located directly over Rosado’s eye was nothing short of hideous. Had there been 40 seconds remaining in the round instead of 40 seconds elapsed, perhaps Rosado might have been allowed to finish the session in order to give his corner a chance to stem the bleeding. But since there were more than two minutes left to fight, stopping the bout made sense.

Rosado may be right when he said during the post-fight presser that Arturo Gatti wouldn’t have fared well in today’s overcautious era, but there’s a fine line between giving fighters a chance to work their way out of trouble and unduly endangering their safety. With Francisco Leal’s death taking place just four days earlier, the sport’s sensitivities were on high alert and Rosado probably was an unfortunate victim of the fallout.

* Just before Deontay Wilder’s bout with Nicolai Firtha, I took an informal poll of adjacent seatmates and each said they didn’t expect the fight to go more than one round. They had good reason to think that way, for the 34-year-old “Stone Man” from Akron, Ohio scaled a jiggly 252¾ and had lost three of his last five fights. As for me, I thought the bout would go three rounds because Firtha showed admirable grit and durability in losing a 10-round decision to future titlist Alexander Povetkin and a 12-round verdict to Johnathon Banks.

All of us – and probably Wilder as well – were surprised by Firtha’s vigorous opening assault that caused the prohibitive favorite to stagger backward from a shotgun jab. But the 2008 Olympic bronze medalist – hence the nickname “Bronze Bomber” – recovered quickly enough to score two knockdowns, first with a jab and then with a one-two. Wilder added a knockdown in round three before a crushing, neck-twisting right to the temple affixed the final exclamation point in round four.

All of us – and probably Wilder as well – were surprised by Firtha’s vigorous opening assault that caused the prohibitive favorite to stagger backward from a shotgun jab. But the 2008 Olympic bronze medalist – hence the nickname “Bronze Bomber” – recovered quickly enough to score two knockdowns, first with a jab and then with a one-two. Wilder added a knockdown in round three before a crushing, neck-twisting right to the temple affixed the final exclamation point in round four.

As has been his custom, Wilder threw more jabs (99) than power punches (54) but his superior activity (153 punches to 94) and accuracy (37 percent to 26 percent overall and 48 percent to 23 percent power) proved pivotal. He out-landed Firtha 54-24 overall, 30-11 in jabs and 26-13 in power shots to earn his 30th straight knockout to begin a career.

At the post-fight press conference, Schaefer painted a scenario in which longtime WBC titlist Vitali Klitschko – who announced he was running for the presidency of Ukraine – would vacate the title, after which Wilder and number-one contender Bermane Stiverne would be matched to fill the void. A smiling and relaxed Wilder appeared as eager to step up his competition as his critics are, saying that he wants no more stay-busy fights. If Wilder-Stiverne can be arranged, it should be an intriguing – and explosive – contest that will surely test the Olympian’s ability to deliver a punch against a higher grade opponent as well as his capacity to take a shot from a legitimate bomber.

*

Aris left the post-fight press conference with mutual friend Ryan Songalia while I grabbed a late-night snack thanks to a McDonald’s drive-thru located near the hotel. I allowed myself to proceed at a leisurely pace thanks to my having scheduled a 4 p.m. flight. After consuming my bounty I took the elevator down to the second floor to print out my boarding pass, then wound down by watching TV until turning out the lights at 3:30 a.m.

Sunday, Oct. 27: Five hours later I awoke to another pretty day – sunny skies and temperatures that promised to touch the 60s. I had until noon to check out of the hotel, so I spent some extra time on the laptop.

About 90 minutes later, the computer began making strange noises – a high-pitched beep followed by a helicopter-like sound. I thought it might have been a video playing in the background so I muted the speakers and closed all the windows. Moments later the noises returned, which told me something had to be wrong, but because the laptop was otherwise working normally I had no idea what it could be. I fired off a few necessary e-mails before shutting it down, then left a message on Canobbio’s cell. Just imagine the chaos had this happened 12 hours earlier.

I checked out of the hotel a little before 11 because I wanted to give myself extra time to get to the airport in case I took a wrong turn or two. After all, my past history suggested such a scenario was likely. For the third consecutive try I couldn’t enter the address I needed – the one for the rental car facility – so instead I used the address for Philadelphia International Airport in the hope that once I got there the signs would lead me where I wanted to go.

Which is exactly what happened. Just like two days earlier, I reached my destination without any trouble and in retrospect I probably could have done it without any navigational help.

It isn’t every day that phobias fall by the wayside but my positive experiences on this trip have greatly reduced my anxiety regarding my Philadelphia-to-Atlantic City route. That’s a good thing, for I found out that I’d be doing shows there on back-to-back weekends in December.

I made such good time that I was able to board a flight scheduled to leave two hours earlier – with no switching fee. Life is good.

For the record, the Travelin’ Man is going to be on the road a lot the rest of this year. Following a two-week break I’ll be flying on five consecutive weeks – Verona, N.Y. from November 15-17, New York City from November 22-24, Quebec City from November 28-December 1 and Atlantic City from December 6-8 and 13-15. I can hardly wait to get started.

Until next time, happy trails.

*

Photos / Naoki Fukuda, Timothy A. Clary-AFP, MAddie Meyer-Getty Images, THE RING, Tom Casino-SHOWTIME

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, W.Va. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 10 writing awards, including seven in the last three years. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales From the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics. To order, please visit Amazon.com or e-mail the author at [email protected] to arrange for autographed copies.