Floyd Mayweather vs. Jim Carrey: A cautionary tale

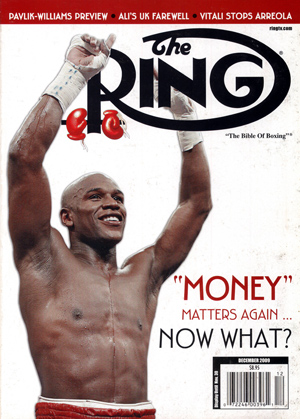

So the champagne has been wrung from the mops, the door to the pay-per-view counting room has been bolted, and the question atop many boxing websites is: What now?

Floyd Mayweather Jr. vs. Canelo Alvarez was an unqualified blockbuster in boxing terms. Every measure that can be applied to a fight has a new benchmark, and everyone who was on the back end earned more money than they’ve ever seen. Those are the same people who before the fight were loudest in saying that Mayweather is “good for boxing.”

And he is, if you’re someone who gets paid when he fights. As Mayweather Promotions CEO Leonard Ellerbe is fond of saying, boxing is a business. To him, and to others with similar job titles, winning a fight happens before the bell, at the negotiating table. That’s where the terms are dictated. If you’re the one dictating the terms, it’s because you’re the “A-side,” and the A-side is for winners.

And of course a business relies on consumers, which in this case is another word for you, the boxing fan. Whether Mayweather is good for you depends on what kind of boxing you like to watch, so that’s not for anyone else to say. A big part of boxing is also arguing about stuff, and he’s always good for inspiring some of that. But whether he could’ve beaten Ray Robinson or Tommy Hearns, or where he stands among the all-time greats, let’s forget it for the time being. He’s better than anyone else right now.

He’s a lot better and he’s a lot richer. Those two achievements will be his legacy. But Floyd’s legacy is oddly where we, the consumers, and Mr. Ellerbe, the businessman, are in one boat and Floyd is in another all by himself. To Floyd, a legacy is the sum of his life’s work, something that will persist beyond him in the form of statistics. To the rest of us, whether we see Mayweather as a once-in-a-lifetime prodigy, or as a beneficiary of soft opposition, or just as a cash cow with its hoof on the throttle of the gravy train, we generally don’t look past what he’s done for us lately; his legacy is our sport at this moment.

So is he good for boxing? Here’s one possible answer:

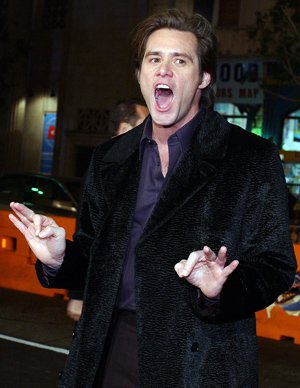

Back in 1996 there was a movie called The Cable Guy. It was notable at the time because it was sort of a dark character study and its star, Jim Carrey, had never done anything besides comedies like Ace Ventura: Pet Detective and Dumb & Dumber. There was no agreement on whether it was good and the movie was considered a flop, but it was significant for another reason: It was the first time an actor was paid $20 million.

Back in 1996 there was a movie called The Cable Guy. It was notable at the time because it was sort of a dark character study and its star, Jim Carrey, had never done anything besides comedies like Ace Ventura: Pet Detective and Dumb & Dumber. There was no agreement on whether it was good and the movie was considered a flop, but it was significant for another reason: It was the first time an actor was paid $20 million.

The effect was immediate in Hollywood. Agents’ phones across town began ringing. Other A-list actors had seized on the number, and before the end of the year something called the “20 million dollar club” had been established. It soon included others like Arnold Schwarzenegger, Tom Cruise, Mel Gibson and John Travolta.

Once the line had been crossed it became the defining mark of a star’s worth. If you weren’t making $20 million per picture, you weren’t a true star. More and more achieved the mark. The first actress to join the club was Julia Roberts for Erin Brockovich in 2000.

This was great for the actors and their agents. After all, movies are a business.

The business of making movies, however, had just become a lot harder. Action movies got even more expensive, and comedies and dramas which had previously required modest budgets to make suddenly saw costs shooting through the roof because of the stars. And with the costs way up there, it meant that the money people had a lot farther to fall if the movie tanked. The result was that producers began to play it very safe. They relied more heavily on scripts that re-hashed proven hits, and sequels to established franchises – movies determined by their savvy projections to have the perfect elements for phase two…

They adopted a much more aggressive, all-in marketing strategy to sell their increasingly crappy movies. They carpet-bombed consumers (again, you) with trailers that were better than the movies themselves – nevermind if they had to give away all the best parts to do so – and plastered ads on every billboard and 24-ounce cup in sight. The idea was to defeat what actually drives a movie’s long-term success – people who have seen it – and make as much money as possible on opening weekend before audiences realized and told each other that the movie sucked. This was seen as controlling a movie’s destiny. Today, movies rely on opening weekends to make as much as half of their budgets back, and a very large chunk of that budget is for marketing.

So, because of agent/talent alliances driving costs too high, studios began to produce safer but unsatisfying products. Simultaneously they relied more on marketing to create hype and convince the public that they were paying for something worthwhile. Sounding familiar yet?

By the time studios realized that they could still lure audiences with no-name actors and better scripts, it was largely too late. There had been too many failures, the money had left for other investment opportunities, cable television had become the new showcase for innovative, quality entertainment, and Netflix had arrived. The movie business had shrunk and was subsisting on calculated tent-pole ventures aimed at the younger demographic which had plenty of other options for entertainment.

A No. 1 movie two weeks in a row became a rarity. People passing up movies for other things became common. High ticket prices became mandatory.

And to top it off, since we don’t live in a world where things get smaller, salaries continued to grow. These days, actors (and some directors) make a lot more than $20 million per picture. They accomplish this with negotiating for “back-end participation.” The A-listers can still get their $20 million up front, but the real money is in the points – a percentage of the movie’s profits. Not the net points, which every Los Angeles fourth-grader knows to avoid, but the gross points. This strategy has led to payoffs of $75 million and beyond.

So back to boxing.

Well, no – one more thing about movies. The thing about movies is that they’ve been saved by the after-market. Sales to foreign distributors have become crucial – some might say the most important consideration for studios these days. The problem with boxing is that it has no after-market. A boxing promotion has only one night to make all its budget back plus profit. In other words, it is all opening weekend.

Mayweather has maximized his income by doing what Hollywood’s A-listers do – he makes money on both ends. He has cornered even more profit for himself by being his own promoter. Plus he can make demands and call shots because he is what even the top movie stars are not: He is irreplaceable.

Mayweather has maximized his income by doing what Hollywood’s A-listers do – he makes money on both ends. He has cornered even more profit for himself by being his own promoter. Plus he can make demands and call shots because he is what even the top movie stars are not: He is irreplaceable.

He’s also very open about his priorities. He recently said, in response to criticism that his opponents have been hand-picked: “If they say these guys were hand-picked, they was hand-picked to make 40 and 50 and 60 million, then you know what? Keep hand-picking them. If they’re going to keep paying, keep hand-picking them.”

At least the guy is honest. So much so that he changed his name to his favorite thing. And you can’t blame him for wanting to make as much of it as possible. But his transformation from “Pretty Boy” to “Money” has brought about a sea-change in boxing that is as profound as Carrey’s $20 million coup.

That shift in the movie industry begat a golden age for agents. In boxing, Mayweather’s alliance with Al Haymon, whom he credits with much of his success, has initiated the age of the “advisor.” (By the way, this might be a good time to admit that I have no idea what the hell Al Haymon actually does, but if I had to pick a word it would probably be “leverage.” It’s enough to note that the consensus choice for “most powerful person in boxing” is not a promoter, or a network executive, or even a fighter, but a Sith-like figure who can only be described with the most nebulous job title ever.)

In Hollywood, the rising cost of stars led to gun-shy studios putting their faith in marketing over compelling material to protect their investments.

In boxing, the rising cost of network stars led to once-a-year fights against soft opposition to protect against a loss, coupled with a reliance on marketing to convince fans that a loss was a real possibility, if not likely.

In the case of each, fans experienced crap-fatigue and rightly began to seek their joy elsewhere.

Boxers have begun to talk about what’s “good for the brand” (meaning themselves). Some won’t even entertain the possibility of a matchup until quibbling out who is recognized as the “A-side” and who is the “B-side.” The standard response now when asking X if he will face Y is, “We’ll see if the money is right.” It’s all about the money. And remember, we’re not talking an extra mortgage payment here, we’re talking about MILL-yuns.

Mayweather has no problem with that. He says he’s the American Dream, making money for his family – not by robbing anyone, but by hard work. True. His fans have no problem with it either. Call it money worship or Money worship, they’ll watch, regardless.

Much of the boxing media has no problem with it – and the members who do still have to cover Mayweather because he’s the biggest thing in the sport. Being the rational sorts, they’ll say, “It’s PRIZE fighting,” emphasizing “prize” to hammer home that fact that money is exchanged. Which I guess proves, once again, that it’s a business. OK, case closed. Since it doesn’t take place in a board room or a closed stockholder meeting, however, but rather in front of a paying audience, I’m going to insist that it is also “entertainment.”

And most fighters would agree with that. I’m sure I’ve heard Floyd himself say it. But the idea behind entertainment, as any nervous producer watching the audience from behind the curtain will tell you, is that the audience – hold on to your hats – is entertained. The success of “entertainment” in Mayweather’s reckoning, and those who work with him, is determined by how many buys and how many butts can be counted. But that’s not entertainment, that’s business. This is why the movie comparison means something, because that industry made the same fatal confusion.

The mark of good entertainment isn’t the level of satisfaction in the performers or the investors. It can certainly be the result, but it decides nothing. Does a show last for weeks on Broadway because its writer is really happy with his percentage? Or is a TV show not canceled because an actress really enjoys playing her character? Does an album go platinum because a singer really likes the way it turned out?

It’s the job of an entertainer to entertain, but an audience decides if it’s entertain-ING. When you have to start tricking your audience to get their money, you’ve got a problem.

And boxing has a problem. Mayweather just took care of the most credible opponent out there – credible meaning the one for which the marketing effect was most successful. (As a side note, a lot of that marketing is targeted directly at the media. Just in the few years I’ve been around boxing, there has been a significant rise in the volume of pre-packaged “storylines” emailed out to media members before a fight card, in which the combatants, who might be from Liverpool, Tijuana, Osaka and Philadelphia, all deliver their supposed quotes with eerily similar voices.)

And even more important than being credible, Alvarez brought with him a huge fanbase – arguably larger than Mayweather’s. Is there anyone out there who can compare? Manny Pacquiao, maybe, if he looks rejuvenated against Brandon Rios. Even then it would be an act of marketing genius to get people believing he could beat the Mayweather that showed up against Canelo. Any promotion trying to convince us that the other names brought up so far pose a threat – Devon Alexander, Amir Khan, Danny Garcia, etc. – would be outright fantasy.

And even more important than being credible, Alvarez brought with him a huge fanbase – arguably larger than Mayweather’s. Is there anyone out there who can compare? Manny Pacquiao, maybe, if he looks rejuvenated against Brandon Rios. Even then it would be an act of marketing genius to get people believing he could beat the Mayweather that showed up against Canelo. Any promotion trying to convince us that the other names brought up so far pose a threat – Devon Alexander, Amir Khan, Danny Garcia, etc. – would be outright fantasy.

But Mayweather is locked into four more fights with Showtime. Or, perhaps more accurately, Showtime is locked into four more fights with Mayweather. That deal, hailed early this year as the ultimate boon, is now looking more like an albatross.

Showtime reportedly lost money when Mayweather fought Robert Guerrero. Alvarez was undoubtedly a different story, but they still have to cover Mayweather’s guaranteed purse four more times. That means marketing, and marketing means here we go again with the propaganda about why the next guy is a threat.

You can say that boxing has always been this way, about promoters hyping fights, but boxing, in the United States anyway, has never had such a problem with capturing an audience. And boxing has never seen the kind of money Mayweather is making. It’s an impossible standard for a sport too small to sustain it. But that won’t stop the next generation from trying, because now they’ve seen those stacks of cash and they can’t be un-seen. Agents (and presumably “advisors”) aren’t paid to be conservative or conciliatory. They want a lot for their clients and they want it now, and then next time they want more. Hollywood learned its limits the same way and never recovered.

But even in an ailing movie industry, there is sometimes an Avatar that saves everyone else. Maybe you can say Mayweather is that. Like Mike Tyson. But let’s be honest: Tyson brought out the Roman in all of us. The casual fan bought in to see a decapitation, no matter how quick, and those fights sold with nothing resembling the press blitz of Mayweather-Alvarez. Without the draw of a sensation like Canelo, will they buy in to see a 12-round display of finesse?

Even if they pick the next guy from further up the scale, and even if HBO, Showtime, and Golden Boy can find it within themselves to sit in the same room, does anyone think that brittle Argentine hero Sergio Martinez has a snowball’s chance in Buenos Aires against Floyd? The answer from the marketing department: “Not YET!” After the press campaign (which, if being genuine, would name the fight “Because Sergio Deserves A Payday”), maybe, but I don’t see how Sept. 14 won’t be remembered as the peak.

Who knows, maybe everything is proceeding as Haymon has foreseen. Maybe the six-fight deal was a calculated hedge on Mayweather’s lack of opposition, and it will actually be HBO who gets the last laugh. And there’s no suggestion here that “something needs to be done about Mayweather.” Again, he’s the best out there at the moment, and in hindsight he was actually the most honest detractor of the Alvarez fight’s significance. Plus the script is pretty much written now: He still has to beat someone at least four more times, and Showtime has to do what it can to cover the cost. But where everyone else is concerned, Mayweather’s legacy is what we’ll get. If it were a movie, this would be the trailer voiceover:

In a world… ruled by PR departments and advisors…one man will fight… for money.

Sounds awesome.

But at least after you walked out halfway through, there wouldn’t be someone at the door trying to convince you that it was a great movie because the theater was full.

This all might sound cynical, but the much more cynical notion is to suggest that value doesn’t matter. That you sell something not by trusting its actual attributes but by hammering your marketing message long enough and loud enough that the consumer takes over the job for you. That star power equals virtue and that profit equals quality.

This is the world that Mayweather has created. And no, it’s not good for boxing. It’s good for Mayweather.

Photos by Ray Tamarra-Gettyimages; Joe Klamar-AFP/Gettyimages, Lucy Nicholson-AFP, Ethan Miller-Getty Images, THE RING

Brian Harty is a contributing editor for THE RING. He can be reached at [email protected]