Aug. 2, 1980: A day that changed boxing

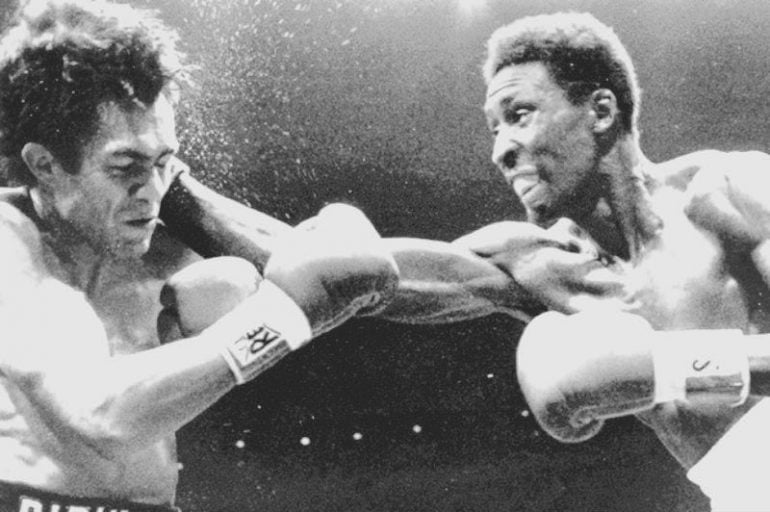

Aaron Pryor (left) lands a hard jab to the face of Antonio Cervantes en route to stopping the Colombian legend in the fourth round to claim the WBA junior welterweight title in Cincinnati, Ohio, on Aug. 2, 1980. Pryor was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1996; Cervantes was inducted in 1998.

As dawn broke on Aug. 2, 1980, boxing fans were prepared to savor a fistic feast. Although a slew of cards were staged in Argentina, Fiji, Ghana, Mexico, Nigeria, the Philippines, South Africa and Zambia, the most attention was centered on two of the three cards held in the United States, where three pillars of the sport prepared to defend their championships.

Antonio Cervantes, Pipino Cuevas and Samuel Serrano each had registered 10 or more defenses of their respective WBA belts, though Cervantes’ total was earned over two reigns. Cervantes was the first to risk his championship, for CBS televised his bout against the dynamic Aaron Pryor in the challenger’s hometown of Cincinnati while Cuevas and Serrano put their titles on the line a few hours later on a closed-circuit card emanating from Detroit’s Joe Louis Arena. Along with a heavyweight slugfest between Randall “Tex” Cobb and Earnie Shavers and Hilmer Kenty’s WBA title bout against obscure (and many said undeserving) mandatory challenger Young-Ho Oh, Serrano fought Japanese bomber Yasutsune Uehara while Cuevas crossed gloves with Detroit hero Thomas “Hit Man” Hearns in the main event.

In less than 12 hours’ time, the boxing world experienced a seismic shift unlike few others in the sport’s history. Three champions that boasted a combined 37 defenses in four reigns spanning 14¼ years lost their belts in crushing fashion. Two of the victors, Hearns and Pryor, went on to join Cervantes and Cuevas in the International Boxing Hall of Fame while Uehara’s one-punch KO victory was so shocking that it was declared THE RING’s 1980 Upset of the Year. What’s more, this destructive swath was paved in a little less than 12 rounds’ time.

Thirty three years ago today, the trio of Hearns, Pryor and Uehara executed a coup of epic proportions. It not only changed the face of the WBA’s championship roster, it also ignited untold excitement amongst the fan base, established a launching pad for three potential new stars and ultimately created an indelible mark on the sport’s lore.

*

Antonio Cervantes had been a 140-pound champion for all but 15 months since October 1972 and the classy Colombian boxer-puncher was among the sport’s most experienced titleholders in terms of ring action. The Pryor fight was to be Cervantes’ 17th defense overall and the seventh of his second reign. Standing a willowy 5-foot-9 and sporting a 72-inch reach, Cervantes used his physique and knowledge to dominate from long range but he also had the power to take out opponents who were too careless in their attempts to get inside his long arms.

At his best, Cervantes was a beautiful blend of science and sock but for most American fight fans he remained a mystery on several levels. First, although his age was listed at 34, some suspected he was as old as 40. Second, his record was a matter of debate. The CBS broadcast of Cervantes-Pryor quoted the Colombian’s record as 85-9-3 (40) but Cervantes estimated he had more than 120 fights. Boxrec.com eventually proved him correct as it listed him at 119-13-4 (50) entering the Pryor fight. Finally, he had appeared on live nationwide TV only once before – CBS aired his commanding 15-round decision over Esteban DeJesus in May 1975 – and during an era that predated widely available home video recorders much less the Internet, Cervantes’ reach within American shores was limited to occasional fight reports in boxing magazines and once-in-a-blue-moon profiles. But for those who saw him live and for those who paid attention to the write-ups, “Kid Pambele” was a genuine legend.

At his best, Cervantes was a beautiful blend of science and sock but for most American fight fans he remained a mystery on several levels. First, although his age was listed at 34, some suspected he was as old as 40. Second, his record was a matter of debate. The CBS broadcast of Cervantes-Pryor quoted the Colombian’s record as 85-9-3 (40) but Cervantes estimated he had more than 120 fights. Boxrec.com eventually proved him correct as it listed him at 119-13-4 (50) entering the Pryor fight. Finally, he had appeared on live nationwide TV only once before – CBS aired his commanding 15-round decision over Esteban DeJesus in May 1975 – and during an era that predated widely available home video recorders much less the Internet, Cervantes’ reach within American shores was limited to occasional fight reports in boxing magazines and once-in-a-blue-moon profiles. But for those who saw him live and for those who paid attention to the write-ups, “Kid Pambele” was a genuine legend.

The reason why Cervantes’ latest title defense was being showcased on CBS was his opponent. Aaron Pryor was an up-from-the-bootstraps star in the making thanks to a whirlwind style that conjured memories of Henry Armstrong, Jack “Kid” Berg, Fighting Harada and Harry Greb. During the early and mid-1970s Pryor was a  standout amateur that harbored dreams of making the 1976 Olympic team, and his 204-16 record gave him reason to believe those dreams would come true. But a pair of close decision losses to eventual gold medalist (and Val Barker Trophy winner) Howard Davis Jr. threw cold water on his aspirations. With Davis wearing the medal he coveted and owning the multi-fight network TV contract that came with it, “The Hawk” was forced to take the long, hard road toward stardom by fighting often for small purses away from TV screens.

standout amateur that harbored dreams of making the 1976 Olympic team, and his 204-16 record gave him reason to believe those dreams would come true. But a pair of close decision losses to eventual gold medalist (and Val Barker Trophy winner) Howard Davis Jr. threw cold water on his aspirations. With Davis wearing the medal he coveted and owning the multi-fight network TV contract that came with it, “The Hawk” was forced to take the long, hard road toward stardom by fighting often for small purses away from TV screens.

One of boxing’s most redeeming qualities is that talent eventually rises toward the top. When that talent includes a magnetic style it was inevitable that boxing’s power brokers took notice. Back-to-back victories over Julio Valdez (KO 4) and Leonidis Asprilla (KO 10) on NBC and CBS ran Pryor’s knockout string to 16 and positioned him for title shots against lightweight belt-holders Jim Watt (WBC) and Kenty (WBA). Neither titleholder was eager to risk their bauble against the likes of Pryor, so “The Hawk” (so named for mentor Ken Hawk as much as for his explosive ring style) was forced to move five pounds up the scale to seek his first championship.

The fiery Pryor further motivated himself by placing photos of Cervantes all around the gym and writing his name on pieces of adhesive tape, all in the name of maintaining focus on his intended prey.

“It motivates you,” Pryor said. “When you’re going four rounds and you look up and see this guy’s name and picture in front of you, it makes you go five or six.”

Cervantes, for his part, was eager to fight the ultra-aggressive challenger.

“That’s my type of fighter,” the classic counter-puncher said through an interpreter. “That’s the kind of fighter I really enjoy fighting because I can really hit him that way.”

Pryor’s manager Buddy LaRosa objected to the WBA’s choices of officials – Fernando Viso of Caracas, Venezuela and Santurce, Puerto Rico’s Ismael Fernandez – as well as the bilingual referee, Larry Rozadilla of Los Angeles, who also was charged with scoring the bout. LaRosa feared the heavily Latin influence would favor the Latin champion of the Latin-based WBA but in the end, Pryor’s fists ended up being judge, jury and executioner.

The bounding Pryor met Cervantes three-quarters of the way across the ring when the opening bell sounded and instantly went to work by swarming him with bunches of punches. Expecting this, Cervantes coolly snapped out jabs, maintained a high guard and kept his eyes peeled for countering opportunities. During those rare times when they were at long range, Cervantes cracked Pryor with long-armed hooks and crosses.

With 30 seconds remaining in an active opening round, Cervantes floored Pryor with a sneaky right to the jaw. Up at one, Pryor whirled his right arm in windmill fashion as Rozadilla administered the mandatory eight count, then proceeded to land the first hook he threw once action resumed. Cervantes affixed a tight clinch, then rode out the rest of the round.

Round two saw plenty of the long-range boxing that favored Cervantes, but it was fought at the kinetic pace that suited Pryor. “Kid Pambele” continued to connect with well-timed counters while the challenger pumped in quick flurries. Pryor then unveiled a wrinkle in his game by suddenly cutting wide circles around the champion and flashing swift, Ali-like jabs. A combination visibly moved Cervantes and Pryor showed off his superior upper body strength by using his shoulders to shrug off Cervantes in the clinches.

Pryor picked up his pace even more in the third and Cervantes had little choice but to do the same lest he be swallowed whole. The champion responded well to the challenge as he landed a meaty right that caused Pryor to fall forward into a clinch but moments earlier a left hand opened a gash under Cervantes’ right eyebrow. As if dealing with Pryor wasn’t enough, the crimson only added to Cervantes’ increasingly desperate situation. Once the blood started gushing into his eye his previously pinpoint punches had a flailing look to them. Not only that, the older champion looked weary, as if he had suddenly hit a wall.

Cervantes’ corner feverishly tended to the cut between rounds but their work did little to ease the crisis as the blood resumed flowing mere seconds into the fourth. The energized Pryor bounced around Cervantes and speared his gory face with jabs and crosses, content to pile up points and inflict ever-mounting damage. Pryor also showcased his underrated defense as he rolled under the champion’s blows.

A triple jab set up a heavy one-two to Cervantes’ face, which then ignited a torrent of punches. A thunderous right to the face floored the Colombian legend near one of the corner pads. Cervantes’ crumpled form turned his back to Rozadilla and Pryor, then tried to rise by pulling on the ropes. His attempts to clear the cobwebs were in vain as Rozadilla tolled the fatal 10.

With the partisan crowd roaring its approval, the new champion shook his hips and soared into the arms of a corner man who raised him toward the heavens. It was the moment Pryor had yearned for ever since he first pulled on the gloves at age 11, and given the beaming smile on his face the reality appeared to exceed the dream.

With the partisan crowd roaring its approval, the new champion shook his hips and soared into the arms of a corner man who raised him toward the heavens. It was the moment Pryor had yearned for ever since he first pulled on the gloves at age 11, and given the beaming smile on his face the reality appeared to exceed the dream.

Pryor was Cincinnati’s first world champion since Wallace “Bud” Smith lost the lightweight title to Joe Brown in August 1956, when Pryor himself was just 10 months old. The result also carried a full-circle effect for Pryor: Riverfront Coliseum, the scene of his greatest triumph to date, was also where Pryor lost the first of his two fights with Davis at the Olympic trials.

As it turned out, Pryor was down on all three scorecards. Cervantes led 29-27 on Viso’s card, 29-26 on Fernandez’s and 28-26 on referee Rozadilla’s.

It’s been written that nothing can keep a good man down. But it helps a lot of that man also happened to be a great fighter.

(Click on the NEXT button on the right to read Page 2 of this article.)