Emile Griffith tribute

Emile Griffith, a three-time welterweight king and a two-time middleweight champion during an era of undisputed titles, died Tuesday at an extended care facility in Hempstead, N.Y. at age 75. In recent years Griffith had struggled with pugilistic dementia, the long-term effects of which eventually required full-time care.

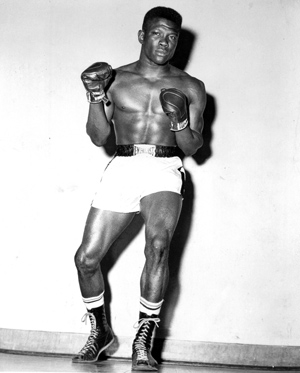

The first boxing champion from the Virgin Islands might never have stepped inside a ring had it not been for Howie Albert’s powers of observation. During one steamy summer day, Griffith, then a 15-year-old shipping clerk at a ladies hat factory, asked to work shirtless.

The first boxing champion from the Virgin Islands might never have stepped inside a ring had it not been for Howie Albert’s powers of observation. During one steamy summer day, Griffith, then a 15-year-old shipping clerk at a ladies hat factory, asked to work shirtless.

“So I went out and took my T-shirt off, the next thing I knew he was peeking at me,” Griffith recalled in Peter Heller’s “In This Corner,” “Why he was peeking at me, I didn’t know what plans he had going through his head at the time. The next thing you know I was in the Golden Gloves.”

Impressed with Griffith’s V-shaped physique, Albert took Griffith to Gil Clancy’s Gym and the kid who originally wanted to be a baseball player began what would become a Hall of Fame boxing career.

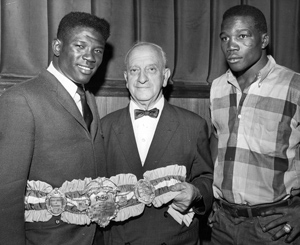

Griffith flourished under Clancy’s tutelage and by age 19 he advanced to the 1957 New York Golden Gloves finals, where he lost a decision to Charles Wormley of the Salem Crescent Athletic Club. The following year Griffith captured the 147-pound Open Championship, defeating Osvaldo Marcano of the PAL’s Lynch Center. With no more amateur mountains to climb, he turned pro shortly thereafter.

Although Griffith stood just 5-foot-7¾, he sported a massive 72-inch reach that allowed him to box at distance and wage war in the trenches with equal dexterity. Because of this versatility, Griffith is generally regarded as one of the sport’s steadiest and most consistent performers.

Griffith won his first 13 fights before losing a 10-round split decision to veteran Randy Sandy in October 1959. Over the next 13 years the losses were few and far between despite fighting relentlessly tough competition. The men he beat in title fights include Benny “Kid” Paret (twice), Gaspar Ortega, Ralph Dupas, Jorge Fernandez, Luis Rodriguez (twice), Dick Tiger, Joey Archer (twice) and Nino Benvenuti. He also holds non-title victories over Tiger, Dupas, Fernandez (twice), Ortega, Denny Moyer (twice), Florentino Fernandez, Yama Bahama, Holly Mims, Andy Heilman, Stanley “Kitten” Hayward, Gyspy Joe Harris, Tom Bogs, Ernie “Indian Red” Lopez (twice), Max Cohen, Armando Muniz, Bennie Briscoe, Donato Paduano and Christy Elliott.

the next 13 years the losses were few and far between despite fighting relentlessly tough competition. The men he beat in title fights include Benny “Kid” Paret (twice), Gaspar Ortega, Ralph Dupas, Jorge Fernandez, Luis Rodriguez (twice), Dick Tiger, Joey Archer (twice) and Nino Benvenuti. He also holds non-title victories over Tiger, Dupas, Fernandez (twice), Ortega, Denny Moyer (twice), Florentino Fernandez, Yama Bahama, Holly Mims, Andy Heilman, Stanley “Kitten” Hayward, Gyspy Joe Harris, Tom Bogs, Ernie “Indian Red” Lopez (twice), Max Cohen, Armando Muniz, Bennie Briscoe, Donato Paduano and Christy Elliott.

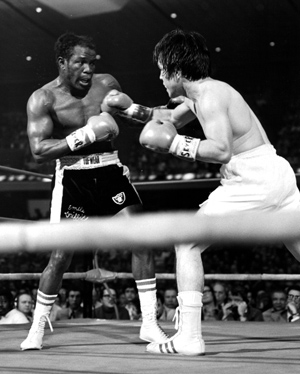

Even deep into his 30s, Griffith’s skills challenged fighters in the midst of their primes. In 1973, a 35-year-old Griffith nearly avenged a 14th-round TKO loss by pushing dominant middleweight champion Carlos Monzon to a close 15-round decision, and at age 38 he came within a few points of dethroning WBC 154-pound titlist Eckhard Dagge in his native Germany.

Half of the losses and both of the draws in his 85-24-2 (23) record occurred during the final 50 months of his career. It ended with three consecutive defeats, the last of which came to future middleweight champion Alan Minter. But when Griffith was at his best, most of the losses only came against other outstanding fighters like Jose Napoles, Monzon, Paret, Moyer, Benvenuti, Rodriguez, Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, Jean-Claude Bouttier and Hayward.

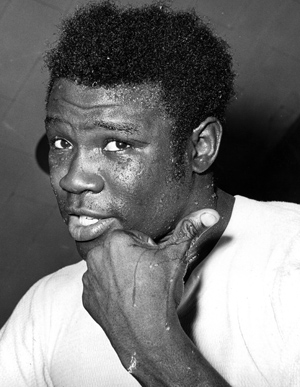

For all of his victories and all of his honors – which included Fighter of the Year awards in 1963 (BWAA) and 1964 (THE RING) as well as the magazine’s 1967 Fight of the Year when he lost to Benvenuti for the first time – Griffith is best known for an overarching tragedy. On March 24, 1962 Griffith fought Paret for the third time and for the second time as a welterweight title challenger. Their pulsating series was saturated with personal tensions, the most infamous of which was Paret calling Griffith a “maricon” – the Spanish equivalent for a homosexual slur – during the weigh-in.

“Maybe it’s worse when someone you know and consider a good person does something really lousy to you than if it is a stranger. All I know is it felt like he stuck a knife into me,” Griffith said in Ron Ross’ book ‘Nine…Ten…and Out!’ “If (Gil) Clancy didn’t jump right in and get between us I was ready to go to it then and there, without gloves, without three-minute rounds and no referee. ‘Save it for tonight, Emile,’ Clancy said as he wrapped his arms around me. ‘Save it for tonight. That’s what he wants to do, get you mad and out of your fight plan.'”

“Maybe it’s worse when someone you know and consider a good person does something really lousy to you than if it is a stranger. All I know is it felt like he stuck a knife into me,” Griffith said in Ron Ross’ book ‘Nine…Ten…and Out!’ “If (Gil) Clancy didn’t jump right in and get between us I was ready to go to it then and there, without gloves, without three-minute rounds and no referee. ‘Save it for tonight, Emile,’ Clancy said as he wrapped his arms around me. ‘Save it for tonight. That’s what he wants to do, get you mad and out of your fight plan.'”

Despite being knocked down with a left hook in round six, Griffith was well ahead on points going into the fateful 12th. Following a listless 11th, Clancy ordered Griffith to not let up if he hurt Paret. The moment of truth arrived a little more than midway into the next round when Griffith staggered Paret with a torrid right to the jaw. With Clancy’s command ringing in his ears, Griffith landed 21 flush shots, mostly to Paret’s battered head, and by the end the Cuban’s body was frighteningly inert, as if his very soul had already exited his body.

Though Griffith was angry at Paret for what he said at the weigh-in, he didn’t hate him – certainly not to the point of killing him.

“I was so afraid for Paret but I was afraid for myself, also,” he said in Ross’ book. “I was feeling a terrible guilt because the truth was, I was angry at him. And seeing the way he was now, I didn’t want to feel that I had any anger towards him. I was angry at him, but it wasn’t hate. It was nothing like hate. At that moment I could not even recognize that there was a difference between anger and hate. I broke down, crying, asking myself if I could have been so angry that I wanted to kill him. I had to admit that I hated him so much for what he said but I really didn’t hate him – the person – Benny Paret.”

Paret’s death 10 days later only marked the beginning of Griffith’s agony, an agony that never left him. That feeling extended to referee Ruby Goldstein, who never officiated another fight.

In the wake of Paret’s death Griffith was taunted in the streets and received hundreds of hateful letters from Paret supporters who believed Griffith had purposely murdered their hero. But their words couldn’t add to the torment Griffith already felt, which often came in the form of nightmares.

Still, he fought the demons day after day but only rarely did the tigerish Griffith re-emerge in the ring. For the most part, Griffith gained satisfaction by out-pointing opponents rather than starching them. After the Paret KO – his 11th – Griffith scored only 12 more knockouts in his final 81 fights.

Following his 1977 retirement, Griffith followed the footsteps of Clancy and uncle Murphy Griffith and became a trainer. His most notable charges were WBC featherweight champion Juan LaPorte and, at times, triple-crown titlist Wilfred Benitez. The connection with Clancy remained strong throughout their lives; in fact, one close acquaintance said that Griffith spoke to Clancy the day before the Hall of Fame trainer died in March 2011.

Following his 1977 retirement, Griffith followed the footsteps of Clancy and uncle Murphy Griffith and became a trainer. His most notable charges were WBC featherweight champion Juan LaPorte and, at times, triple-crown titlist Wilfred Benitez. The connection with Clancy remained strong throughout their lives; in fact, one close acquaintance said that Griffith spoke to Clancy the day before the Hall of Fame trainer died in March 2011.

He was elected to the World Boxing Hall of Fame in 1984 and in 1989 he was named one of the charter inductees at the International Boxing Hall of Fame (officially inducted in 1990). But as wonderful as those moments must have been for Griffith, he experienced a profound catharsis on Nov. 8, 2003 when Paret’s son Benny Jr. embraced Griffith and expressed his forgiveness.

The moment was captured in the 2005 documentary “Ring of Fire: The Emile Griffith Story,” but not all was complete because Paret’s widow Lucy, who died in 2004, couldn’t bear to see Griffith again.

The final years of Griffith’s life were not healthy ones as the effects of pugilistic dementia set in. His happy-go-lucky personality was replaced by extreme suspicion and the changes sometimes manifested themselves in public. One particularly uncomfortable moment occurred during a Friday night event at one International Boxing Hall of Fame induction weekend when a confused and frightened Griffith failed to recognize Benvenuti and struck him on the arm. The understanding Benvenuti simply smiled and gently led Griffith back to his seat.

But the memories of his final years should be superceded by the glories of his youth. The beautiful blend of boxing skills and underrated fury, the many triumphs and accomplishments inside the ring and the nights of victory in the corner. He will also be remembered for the 23 occasions he headlined at Madison Square Garden, boxing’s most celebrated shrine.

His is a presence that boxing, and those who love it, will miss from this day forward.

*

Photos / THE RING

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, W.Va. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 10 writing awards, including seven in the last three years. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales From the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics. To order, please visit Amazon.com or e-mail the author at [email protected] to arrange for autographed copies.