Time Machine: McKinney vs. Ncita

On Saturday, Nonito Donaire and Guillermo Rigondeaux will write the latest chapter in the 122-pound division’s relatively brief but demonstrably robust history. Some of the sport’s greatest battles have occurred at junior featherweight, with Wilfredo Gomez’s victory over Lupe Pintor topping most lists. In honor of Donaire-Rigondeaux, RingTV.com’s resident historian Lee Groves relives one of the division’s underrated classics, Kennedy McKinney’s knockout of Welcome Ncita in December 1992.

*

If ever a fight summarized a boxer’s rocky road to success, it was Kennedy McKinney’s title-winning come-from-behind 11th round knockout over Welcome Ncita. On that fateful late autumn night in 1992 thousands of miles away from his Mississippi birthplace and his Las Vegas residence, McKinney displayed the gifts that vaulted him toward the pinnacle of his sport, endured several difficulties along the way – some self-imposed, others forced on him – and emerged victorious in the end.

McKinney first vaulted to prominence by improbably making the 1988 U.S. Olympic team. Up until then McKinney had been good enough to advance in tournaments but not to complete the final step. In 1985 and 1986 McKinney lost to future teammate Arthur Johnson in the U.S. Amateur Championships at flyweight while in 1987 and 1988 he lost to bantamweights Michael Collins (semifinal) and Jemal Hinton (final). Still, McKinney qualified for the 1988 Olympic trials but to make the team he had to go through the men who had stood in his way.

McKinney first vaulted to prominence by improbably making the 1988 U.S. Olympic team. Up until then McKinney had been good enough to advance in tournaments but not to complete the final step. In 1985 and 1986 McKinney lost to future teammate Arthur Johnson in the U.S. Amateur Championships at flyweight while in 1987 and 1988 he lost to bantamweights Michael Collins (semifinal) and Jemal Hinton (final). Still, McKinney qualified for the 1988 Olympic trials but to make the team he had to go through the men who had stood in his way.

In the semifinal against the southpaw Collins, McKinney was dropped by a stiff right hook to the jaw but that moment of difficulty was trumped by enough skillful boxing to earn a 4-1 decision and a spot in the final against Hinton, a member of Sugar Ray Leonard’s boxing club. Following three rounds of furious action, McKinney used a final minute surge to earn a 5-0 verdict – and the top spot in the box-off.

There, McKinney met Collins again and by winning the trials, he only had to win this fight to cement his spot. If he lost, he got another chance. In the end, he needed it.

Though many thought McKinney’s stirring third round rally was enough to pull out the victory he lost a 4-1 decision to force a winner-take-all showdown the following day. This time McKinney gutted out the victory and stamped his ticket to Seoul. The Army man whipped himself into prime shape and sailed through the field, stopping Guatemala’s Giovanni Perez and Thailand’s Phajol Moolsan in the first round and out-pointing Steve Mwema before doing the same to Bulgaria’s Aleksandar Hristov to win the gold.

McKinney, now flush with success, felt entitled to celebrate it. That process nearly snuffed out his seemingly limitless future.

“Working so hard to get the gold medal, and being so determined… when I got back it was party time,” McKinney told the Los Angeles Times in 1989. “That’s basically what it came down to. I just partied a little too much. I wasn’t much of a party type until then. When I came back, it was just time to party with the guys. Either they had tried out for the (Olympics) or they had seen me on TV. It was there waiting on me, I guess. It was beer drinking and going out to the clubs. Going out and having fun with your friends until 3 or 4. At that time I didn’t have to be in (at a certain time. But) I had to be in because I had a fianc├®e and I couldn’t neglect her.”

Once he moved from Texas to Las Vegas in January 1989 McKinney, by then honorably discharged from the Army, kept mixing business with pleasure. In his pro debut he stopped David Allers in two rounds on the Roberto Duran-Iran Barkley undercard and 29 days later he polished off Charles Hawkins in one round. Now married, McKinney was working hard – and playing hard too.

“The party just kept going,” he told the Times. “I was enjoying it. I felt I owed it to myself. It did get out of hand. It started in Texas, I guess you could say I brought it here.”

The hard pace he was setting outside the ring began to take a toll. His mind eventually focused more on the perks than the prize ring and his performances reflected his shifting priorities. He won unimpressive decisions over Damian Sutton and David Moreno, the latter of which was on the Sugar Ray Leonard-Thomas Hearns II bill. The disappointing performances drove him deeper into his substance abuse and cocaine soon became a part of his life.

He failed two drug tests and checked into a 28-day drug rehab program. After completing the program he suffered the first blemish of his career when an accidental butt opened a cut on David Sanchez that forced a two-round technical draw. Though McKinney fully controlled the action to that point, the thought of his perfect record going away plunged him into despair.

“It was my very first draw,” McKinney told the Times. “It was hard to deal with. I swallowed that with a big lump. It hurt. I can’t believe that was on my record. I guess it got me down a little bit. That was a period of an emotional letdown. That draw took so much out of me. It took a lot out of my training. It had a bad effect on me.”

The next several months was a swirl of troubles: He left town for three days without telling anyone. He was arrested in connection with an attempted kidnapping but after spending four days and three nights in jail the charges were dropped due to insufficient evidence. His relationship with Top Rank was badly strained, especially after he tested positive for cocaine following a Halloween 1989 split-decision victory over Jose Luis Martinez.

At this point McKinney had hit bottom. But McKinney had always been a fighter at heart and that wellspring of determination eventually lifted him out of the abyss.

Along with Vince Phillips, who was dealing with his own substance abuse issues, McKinney moved to Pahrump, Nevada, 60 miles west of Las Vegas to live with Top Rank employee Bruce Blair, a onetime collegiate boxing champion charged with helping them conquer their challenges. A clean, focused and re-energized McKinney returned to the ring nearly six months later and during a 66-day stretch he scored five straight knockouts. Following an eight-round decision over Jorge Rodriguez, McKinney came full circle by scoring a dominating points win over Jose Luis Martinez, the man who had previously taken McKinney to a split decision.

McKinney continued to stay active, notching six more wins in 1990 and going 6-0 (4) in 1991. McKinney began 1992 by winning the USBA bantamweight title with an impressive near-shutout of former 115-pound titleholder Sugar Baby Rojas and followed up with a six round TKO over onetime 122-pound king Paul Banke on the Iran Barkley-Thomas Hearns pay-per-view undercard. The Banke win vaulted McKinney, now 21-0-1 (13) into his first shot at a major title.

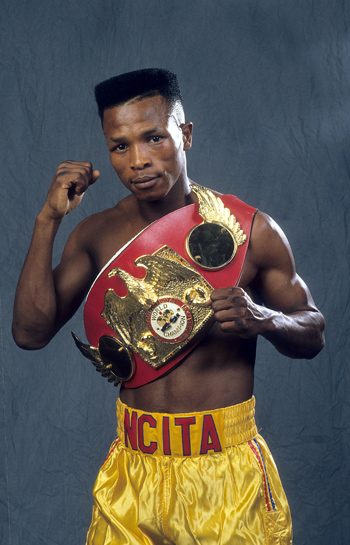

The opponent: IBF junior featherweight king Welcome Ncita.

At age 27, Ncita was at the height of his powers and fit in nicely with fellow titlists Wilfredo Vazquez Sr. (WBA), Tracy Harris Patterson (WBC) and Duke McKenzie (WBO). He was the longest reigning titlist of the group and he earned that status with a formidable blend of hand and foot speed, unpredictable upper body movement, intelligent shot selection and excellent stamina. Ncita was only the second black South African to win a major title (WBA flyweight titlist Peter Mathebula was the first) and he came into the McKinney match undefeated in 31 fights and with six successful defenses since dethroning Fabrice Benichou in Tel Aviv in March 1990.

At age 27, Ncita was at the height of his powers and fit in nicely with fellow titlists Wilfredo Vazquez Sr. (WBA), Tracy Harris Patterson (WBC) and Duke McKenzie (WBO). He was the longest reigning titlist of the group and he earned that status with a formidable blend of hand and foot speed, unpredictable upper body movement, intelligent shot selection and excellent stamina. Ncita was only the second black South African to win a major title (WBA flyweight titlist Peter Mathebula was the first) and he came into the McKinney match undefeated in 31 fights and with six successful defenses since dethroning Fabrice Benichou in Tel Aviv in March 1990.

For all of his accomplishments, however, Ncita’s reign was uneven in quality. While he looked terrific in beating Ramon Cruz (KO 7), Gerardo Lopez (KO 8), Hurley Snead (W 12) and Jesus Salud (W 12), he was extremely fortunate to keep his belt against Sugar Baby Rojas in their first fight, an off-the-floor split decision victory. Ncita was more convincing in the rematch staged seven months later, but his most recent performance against Salud seemingly put him back on track.

The Ncita-McKinney fight was held at the cozy Teatro Tenda in Tortoli, Sardinia, Italy. Ncita was well known in Italy because four of his title fights had taken place there but to them, McKinney was a complete stranger. In fact, McKinney had fought only once outside the U.S. – a two round KO over a 1-7 Reggie Johnson in Red Deer, Alberta, Canada in his first post-rehab outing. Because the 5-foot-7 McKinney enjoyed a one-and-a-half inch height advantage and his 68-inch wingspan was two inches longer, Ncita was placed in an uncomfortable strategic predicament: Instead of exercising his usual stick-and-move tactics he would be forced to adopt an in-and-out blueprint in order to pile up points while minimizing his exposure to McKinney’s powerful weaponry. With only 15 knockouts in 32 wins, Ncita knew victory would probably mean a long night’s work.

Ncita couldn’t have asked for a better opening round, for his jack-in-the-box upper body movement and ambidextrous circling disrupted McKinney’s timing while his swift straight shots repeatedly sliced through the challenger’s guard. Ncita’s diversified attack and constant motion kept McKinney from launching a sustained attack and a left hook that clanged off the American’s jaw capped off a dominant opening three minutes.

Ncita’s quicker fists – and unusual aggression – enabled him to control the first half of round two. At one point Ncita landed a triple hook; two to the body followed by one off the top of the head. A tiny swelling erupted under McKinney’s right eye but the challenger remained unfazed. He stalked Ncita relentlessly and focused most of his work to the South African’s body, a smart long-term strategy designed to sap the champion’s outstanding leg strength. The round’s final moments saw McKinney land his first significant punch, a hearty left to the face.

The stiffness and lack of rhythm that gripped McKinney in the fight’s opening six minutes began to loosen in round three. A right to the ear nailed Ncita with 1:19 remaining and the punch ignited the challenger’s best sequence to date as well as his first winning round. McKinney built on his momentum at the start of round four by landing a sharp jab to the face and followed up with several chopping rights to the ear.

The good news for McKinney was that Ncita had eschewed his textbook boxing and instead was in a fighting froth. The bad news was that Ncita was faring pretty well thus far.

The action in round five see-sawed throughout but McKinney was landing the harder punches while Ncita was fighting with uncustomary wildness. McKinney’s snappy lead right over Ncita’s sloppy left hook briefly buckled the champion’s knees in the round’s final minute but Ncita managed to recover enough strength to hold his own for the rest of the session and open a nick on the corner of the challenger’s right eye.

Ncita reversed the momentum in round six by out-hustling McKinney, but the challenger’s superior size and power presented a never-ending threat. His plight was best illustrated by a sequence that unfolded near round’s end: Ncita uncorked a strong right that swiveled McKinney’s head but the unruffled challenger instantly retaliated with an even more potent right that stopped Ncita’s momentum cold.

Convinced he had taken McKinney’s best and lived to tell about it, an emboldened Ncita accelerated his attack in the seventh while the challenger’s sharpness and technique began to flag. Ncita invested so much power into one hook that he spun himself into the canvas after missing it. Ncita was working in threes and fours while McKinney sputtered in ones and twos. Still, McKinney found a spark in the final minute by landing downward rights with more authority and one-twos that forcefully snapped Ncita’s head. With some in the crowd chanting “Kennedy! Kennedy!” the object of their affection capped his excellent surge with a jab-cross to the jaw.

McKinney continued his rally in the eighth, prompting his corner to shout, “he’s tired now! He’s tired now!” Ncita’s vaunted technique now was absent and his approach was reactive rather than proactive. McKinney’s confidence soared in the ninth as he trapped Ncita on the ropes, an unthinkable proposition given Ncita’s early-round elusiveness. McKinney pounced on every opening, especially with sharp rights following Ncita misses.

Both men looked to make statements in the 10th and they invested every ounce of strength behind each blow. But Ncita, sensing his reign was in jeopardy, summoned an inspired rally. He shoeshined combinations to McKinney’s body and a wicked right to the jaw had the challenger on unsteady legs. With startling suddenness McKinney’s hands dropped to chest level and his normally bright eyes had a slightly glassy and dazed look to them. Ncita seized on McKinney’s uncertain body language and proceeded to hammer him with right hands until the bell.

“OK, it’s all on the goddamn line now,” McKinney’s chief second Kenny Adams declared with his customary bluntness. “The only way you’re gonna win this fight is to knock him out, you understand?”

Though Adams couldn’t have known it at the time, he was correct: Entering the 11th McKinney trailed on all three cards (96-95, 96-94 and 97-94) and the only way to ensure a victory was to score at least a knockdown, if not a knockout.

Though Adams couldn’t have known it at the time, he was correct: Entering the 11th McKinney trailed on all three cards (96-95, 96-94 and 97-94) and the only way to ensure a victory was to score at least a knockdown, if not a knockout.

But Ncita wasn’t in the mood to earn a points win; he wanted blood and he wanted it now. After Ncita landed a right to the side of the head and a clean, whistling hook to McKinney’s jaw, the challenger dropped his hands, turned away, walked toward his corner and took a knee. For an instant it appeared McKinney was giving up on his dream of becoming a world champion while also throwing away all the hard work it took to get to this point. But any negative thoughts he might have had were fleeting, for he was up by referee Steve Smoger’s count of three.

Ncita gunned for the finish with both hands blazing but McKinney proved he was up to the challenge by landing a short right-left to the jaw that temporarily stopped Ncita’s advance. Ncita maneuvered McKinney to the ropes and peppered the challenger with soft but scoring flurries. McKinney responded with his own volleys and soon the pair was locked in a thrilling exchange.

Just before the round entered its final minute, the final stroke of this underappreciated masterpiece was revealed to the world.

A split second after Ncita landed a right to McKinney’s face, the challenger rolled away, lined up the champion’s suddenly exposed chin and unleashed a lead right that connected with ultimate flushness. Ncita’s neck spun violently, his body went limp and the back of his head struck the canvas with a thud. As McKinney marched toward the farthest neutral corner with both arms upraised, Ncita’s stricken body was in the classic spread-eagle pose. Referee Steve Smoger kneeled near Ncita’s body and did his best to shout the count over the din but all the South African could do was roll onto his left side. When Smoger counted “10” at the 2:48 mark of round 11, he certified one of the most dramatic in-round turnarounds in title fight competition.

“They could have counted to a thousand,” declared McKinney’s manager Akbar Muhammad in the September 1993 issue of KO. “No way was Ncita going to get up.”

“Now I want the other two belts,” McKinney said in the April 1993 issue of KO. “The way I see it, the other champions are just holding my belts for me. I intend to beat them and go on to become an all-time great.”

Just as McKinney had climbed off the floor to conquer his addictions, “The King” had lifted himself from the canvas to achieve his ultimate professional dream – a world title belt and the lifelong privilege of being called “champion.”

Epilogue: Given the ebbs and flows of this meeting a rematch was a natural and it was staged April 16, 1994 at the Convention Center in South Padre Island, Texas. By then McKinney had notched four defenses against Richard Duran (W 12), Rudy Zavala (KO 3), Jesus Salud (W 12) and Jose Rincones (KO 5) while Ncita scored two early knockouts over journeymen Eddie Rangel (KO 3) and Kenny Mitchell (KO 2).

The rematch was hard-fought but didn’t quite live up to the original. McKinney survived a fifth-round knockdown but starting in the sixth Ncita’s left eye began to swell. By the eighth McKinney’s persistent jabs left Ncita’s eye a virtual slit and in the end the American kept his title via majority decision as Torben Seemann Hansen’s 114-114 score was trumped by Barry Yeats’ 117-111 count and Vaughn LaPrade’s 117-110 assessment.

Ncita rolled off six straight wins to earn a December 1997 fight with Hector Lizarraga for the IBF featherweight title vacated by Naseem Hamed. Ncita was favored to beat the 34-8-5 Lizarraga but the Mexican, who entered the bout on a 17-0-1 string, dominated the action and caused Ncita to retire on his stool following round 10. Ncita took the next 10 months off before meeting former WBO featherweight titlist Steve Robinson in East London, South Africa for a regional title. The bout ended in a split draw and soon after Ncita announced his retirement. His final record was 40-3-1 (21).

Four months after winning the Ncita rematch, McKinney traveled to South Africa to take on local favorite Vuyani Bungu. Though shorter than McKinney, Bungu’s neat boxing led to a unanimous decision victory so shocking that THE RING deemed the result its 1994 Upset of the Year.

From that point forward McKinney’s career was a series of fits and starts. He returned to the ring against the 21-0 John Lowey a full year after losing to Bungu and following a nip-and-tuck battle McKinney scored an eighth round TKO. That victory earned McKinney a crack at WBO super bantamweight titlist Marco Antonio Barrera, whose record was a formidable 39-0. Their February 1996 fight was a classic as both men tasted canvas before a winner was determined. While Barrera suffered a knockdown in round 11, McKinney was floored twice in round eight, once in round nine and two more times in the 12th before referee Pat Russell stopped the bout at 2:05 of the final round.

From that point forward McKinney’s career was a series of fits and starts. He returned to the ring against the 21-0 John Lowey a full year after losing to Bungu and following a nip-and-tuck battle McKinney scored an eighth round TKO. That victory earned McKinney a crack at WBO super bantamweight titlist Marco Antonio Barrera, whose record was a formidable 39-0. Their February 1996 fight was a classic as both men tasted canvas before a winner was determined. While Barrera suffered a knockdown in round 11, McKinney was floored twice in round eight, once in round nine and two more times in the 12th before referee Pat Russell stopped the bout at 2:05 of the final round.

A pair of victories over Johnny Lewus (W 12) and Nestor Lopez (a split decision 10-rounder) netted McKinney a rematch with Bungu. Unhappily for McKinney, Bungu retained the title via split decision. But McKinney remained a force within the division, and victories over Hector Acero-Sanchez (W 12) and Luigi Camputaro (KO 5) were enough to gain him a fight with Junior Jones, whose own flagging star was re-ignited with back-to-back victories over Barrera to win, then retain, the WBO super bantamweight title.

The McKinney-Jones clash at Madison Square Garden was a Closet Classic only because the main event – Naseem Hamed’s six-knockdown war with Kevin Kelley – was even more spectacular. For the second time in his career, McKinney captured a major title by surviving his own knockdown (this time in round three) only to stop his opponent shortly thereafter (in round four).

Eleven months later McKinney moved up in weight to fight WBC featherweight king Luisito Espinosa, who flattened McKinney in three minutes forty-seven seconds. It would be McKinney’s final title fight. A win (W 10 Mario Diaz) and a loss (L 10 Jorge Antonio Paredes) prompted a three year retirement, after which he returned with a pair of six-round decision wins over Gene Vassar and Joseph Figueroa in April and June 2002. McKinney’s boxing career ended on April 4, 2003 at the Mohegan Sun when the 37-year-old lost a six-round unanimous decision to Greg Torres. McKinney’s final record stands at 36-6-1 (19).

*

Photos / THE RING, Gary Newkirk-Getty Images, Jed Jacobsohn-Getty Images

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, W.Va. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 10 writing awards, including seven in the last three years. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales From the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics. To order, please visit Amazon.com or e-mail the author at [email protected] arrange for autographed copies.