Hauser: Literary notes and other musings

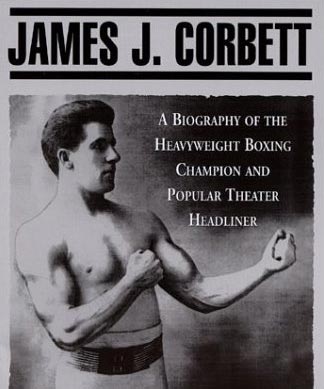

Biographies of boxing’s early gloved champions tend to be lacking when discussing their subject away from the prize ring. James J. Corbett by Armond Fields (McFarland & Company) is an intriguing book, in large part because it breaks that mold.

Fields, who died in 2008, was a social historian who wrote extensively about the early days of popular American theater. James J. Corbett is as much about Corbett the actor as it is about Corbett the fighter.

Beginning in 1892 (the year that he defeated John L. Sullivan) Corbett embarked on a theatrical career that was noteworthy for its success, variety and longevity. He began in vaudeville, made numerous forays into legitimate theater and worked hard to develop his craft as a stage performer. Later in life, he appeared in feature films.

At times, Fields’s recitation of Corbett’s acting credits is repetitious. Corbett was onstage for 39 of his 66 years, and there are moments when it seems as though the author is determined to recite the particulars of every performance. Be that as it may, vaudeville and theater in Corbett’s era and his place within that realm come to life in the pages of this book.

Fields also offers readers an engaging look at the San Francisco that Corbett grew up in as well as Corbett’s personal life. Of particular interest here are the break-up of the fighter’s marriage to Olive Lake in 1895 as a consequence of his affair with Vera Stanwood (who he later married, to the delight of the tabloid press) and the deteriorating mental condition of his father. Patrick Corbett ultimately shot Jim’s mother to death as she slept and then turned the gun on himself.

As far as boxing is concerned, Fields crafts an interesting portrait of Corbett’s amateur career and his relationship with the Olympic Club in San Francisco, where his ring skills matured. But the author falls short of capturing the drama of big fights, especially fights for the heavyweight championship of the world.

That said, Fields succeeds in portraying Corbett as a full flesh-and-blood figure, rather than a cardboard cutout from the distant past. He is on firm ground when he writes, “Corbett changed the public role of a champion, dressing like a gentleman, behaving like a college graduate and greeting the world with a smile instead of a scowl.” And the words resonate when he quotes W.O. McGeehan (one of the premier sportswriters of his time), who wrote upon Corbett’s passing in 1933, “With the death of James J. Corbett, another figure of the romantic era of the American prize ring passes into the twilight of the modern demigods.”

* * *

The book 100 Years of Boxing, published by Ammonite Press, is a collection of 300 photographs chosen by the Press Association, which has offices in the United Kingdom and Ireland and claims more than 18,000,000 images in its photo archives.

The photos show hundreds of boxers from club fighters to all-time greats, in and out of the ring. All of the images are nicely reproduced. Quite a few are different from what we’ve seen before. Some great fighters who are known largely as names in a record book come to life in 100 Years of Boxing.

* * *

I didn’t enjoy the first fifteen minutes of The Fighter (the recently-released feature film based on the life of Micky Ward). The factual distortions and other departures from reality bothered me. Then I told myself, “Relax. This isn’t a documentary. Forget about the nuts-and-bolts realities of boxing and the real Micky Ward. Treat it like fiction and enjoy the show.”

Viewed in that light, The Fighter is worth seeing. Sterling performances by Christian Bale (as Dickie Eklund), Amy Adams (as Micky’s girlfriend, Charlene) and Melissa Leo (as Alice Ward, the conniving matriach of the dysfunctional Ward clan) give it extra impact.

* * *

In the past, I've recounted the memories of various boxing personalities regarding the first professional fight they ever saw. The recollections of three more people who have left their mark on the sweet science follow:

PAT LYNCH, ARTURO GATTI’S MANAGER: It was Bobby Czyz against Mustafa Hamsho at Convention Hall in Atlantic City [on November 20, 1982]. I had a friend named Oscar Saffrin, who was 30 years older than I was. He and his wife gambled a lot, so they’d been comped by Bally’s and invited me and my girlfriend to the fight. I was a boxing fan, but I’d never been to a live fight before. We got there during the preliminaries and sat in the second row. To be that close, to see the punches that way, to hear the punches, I was like, “Wow! This is different from televsion.” I was in awe.

The place was packed. Czyz was undefeated, and his fans had come by the busload to see him. They went berserk when he got in the ring. Then the bell rang and Hamsho put a beating on him. Bobby was never in the fight. He lost a 10-round decision. Mustafa manhandled him. But what impressed me most was the punishment each guy took. Watching a fight on television, you see the impact of the big punches but not punch after punch after punch. That afternoon completely changed my understanding of boxing and my appreciation for what fighters go through.”

Seven or eight years after that, I got into boxing on my own. Joe Gatti was the first fighter I managed. Then I managed Arturo. Oscar Saffrin died before I got in the business, which is a shame. I would have loved to have taken him to one of Arturo’s fights, sat him in the second row, and said, “Thank you. You got me hooked on this. I am where I am in boxing now because of you.”

* * *

RAY MANCINI, FORMER TITLEHOLDER: I was 9 years old. I’d grown up with boxing because of my father and been to amateur fights before. I knew in my heart that I’d be fighting professionally some day.

There was a guy from Buffalo named Dick Topinko who was fighting in the semi-final at the Struthers Field House [in Mancini’s hometown of Youngstown, Ohio, on March 31, 1970]. My uncle was working his corner. Topinko came in for the weigh-in on the morning of the fight and spent the day at our house. Part of that time, he took a nap in my bed. Then my father took me to the fights. Topinko won. A heavyweight from Youngstown named Ted Gullick won in the main event. And nine years later, I made my pro debut at Struthers Field House.

* * *

KEVIN IOLE, YAHOO! SPORTS BOXING WRITER: My dad was a big boxing fan. He’d boxed in the Army. His favorite fighters were Rocky Marciano and Sugar Ray Robinson. He asked what I wanted for my sixth birthday, and I told him I wanted to see Sugar Ray Robinson [Robinson was fighting Joey Archer at Civic Arena in Pittsburgh on Nov. 10, 1965, in what would be the last fight of his career].

My memory of that night is overwhelming. The arena was dark. Bright light was shining on this grand stage, this alter, that men were fighting on. Ray came down the aisle for the main event and the crowd was roaring. I don’t remember much about the fight itself. I know from reading about it later on that Ray was knocked down, but I don’t remember that happening. I do remember being disappointed that he lost. And I remember that his hair, which had been so perfect when he entered the ring, was tousled afterward.

My father died in 2003, so he lived to see me covering boxing. He’d ask me from time to time, “Does Oscar De La Hoya know your name? Does Mike Tyson know your name?” I’d tell him yes, and he loved it. The first time I met Ali, I called my father to tell him about it. Both of us were excited. But seeing Sugar Ray Robinson fight that night has always been hugely significant to me because I saw the Babe Ruth of our sport.

Thomas Hauser can be reached by email at [email protected]. His most recent book, Waiting For Carver Boyd, was published by JR Books and is available at http://www.amazon.co.uk/ or http://www.abebooks.com.