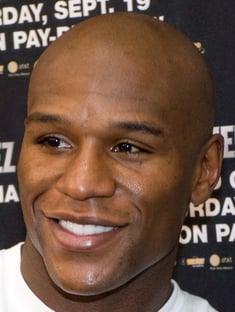

The conflicting sides of Floyd Mayweather Jr.

Floyd Mayweather Jr. last week attacked Manny Pacquiao in a racist and homophobic rant on Ustream and then apologized, revealing his worst and then more-sensible sides in a matter of a few days. The following story was written long before Mayweather’s latest transgression and appeared in the August issue of THE RING magazine. It is meant to give you some insight into what makes him tick.

Floyd Mayweather stood there with a sheepish grin on his face that was almost childlike, momentarily away from the insulating enclave that seems constantly tethered to him. He was shaking hands and mingling with everyone who passed by him in the congested nightclub, where just walking a few feet meant a long wait. Clusters of fans were there to pay homage to arguably the best fighter in the world.

For once, Mayweather was relaxed, showing a much different side of himself than he had in the days leading up to his fight with Shane Mosley. He wasn’t combative or rebellious. He wasn’t screaming about how great he is. In many ways he was like the portrait of him on the side of the Mayweather tour bus parked out front of the MGM Grand: The shot of the toddler with the uneven Afro in boxing gloves that come up almost to his shoulders.

What remains of that little boy, the charming “Little Floyd”, is difficult to tell. The picture of him on the bus is a starkly contrasting image compared to the many brash likenesses of his alter ego, “Money May.” You can’t help but wonder whether Floyd Mayweather is channeling the public persona “Money,” or is Money channeling Little Floyd?

It wasn’t always that way. Before the pumped-up bodyguards and myriad sycophants that surround him today, before the distorted, twisted version of Money arrived, he was just Little Floyd, an approachable, affable rising star.

Remarkably, Little Floyd reappeared after he dominated Mosley on May 1 at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas. Once again, he was the reverent, gregarious Floyd and generously spent three hours with the media after the fight. Many of the same media that had bashed him before the Mosley fight as a haughty ingrate were by then feeding out of the palms of his hands.

Mayweather conducted the interviews while being barraged by autograph seekers, whom he seemed happy to accommodate. They were some of the same fans that he’d blown off just days before.

“Is that the same guy that walked right by me Wednesday?” asked one fan to another who sneaked into the media room to get a glove signed.

Mayweather can have that kind of polarizing effect on people. He doesn’t mind if you hate the public Floyd who’s in front of the cameras, though privately, when you’re sitting with him one-on-one, Mayweather presents a much different picture of himself.

“I do want people to like me and follow me,” Mayweather admitted in a hushed tone, away from his minions, away from the hoopla that seems to follow him everywhere he goes. “No, I don’t want to be looked at as a bad guy, because I know I’m not a bad guy, not to anyone who knows me. There is a lot of Little Floyd, you might say, still in me. But people and fans, and especially the media, have to understand, you have to do certain things to sell a fight. There’s a certain part of you that you have to give up. I suppose that’s the Little Floyd side of me.

“Yes, I am Money Mayweather, the guy who likes to throw money at TV cameras and likes to walk around with a fat wad in my pocket. But I’m also a father now, too, and I have kids to feed. That image keeps me in a million-dollar mansion and takes care of my family and my kids. If people have a problem with that, f— ’em, I can’t help that. Like I said, ‘Like me, hate me, as long as you put your money down to watch me.’ I think fans need to know there is a difference between the public me and the private me.”

But the public very rarely gets a glimpse into that private world. Sure, HBO’s 24/7 tries to provide vignettes as to who Mayweather really is, but much of that is contrived for the cameras. An army of psychologists might be necessary to peel through his competing personalities and truly figure out this man.

Still, his image as a rich, spoiled brat in many peoples’ eyes constantly follows at him. He says he doesn’t mind it, though deep down, you can’t help but sense he’s disappointed by it.

“I really don’t know what more I have to do,” Mayweather said. “I do everything fans want, yes, I really think I do. They want me to fight [Oscar] De La Hoya, I beat De La Hoya. They want me to fight [Ricky] Hatton, I beat Hatton. When the [Manny] Pacquiao fight fell through, who was the best option out there, Mosley, right? I beat him, and now it’s back to Pacquiao again. It’s frustrating. I really think it’s a respect thing. Look, I’m the best fighter of this generation, no one is better than me, and it’s like people can’t get enough.

“What they really want to see is me get my ass kicked. I know that’s never going to happen, because I’ll get out before I get too old and lose what I have. I’m too smart for that.”

Mayweather remains many things to many people. To Floyd’s grandmother, Bernice Mayweather, with whom the then-16-year-old Floyd lived after Floyd Sr. went to federal prison for smuggling cocaine, he’s always going to be Little Floyd.

After the Mosley fight, Bernice stood there beaming at her grandson while waiting patiently for the press to disperse from the impromptu press gathering after the official press conference. She has watched Grand Rapids, Mich., Mayweather’s hometown, come alive each time Floyd’s arrived back after another big victory. The radiantly smiling, happy-to-be-photographed-with-schoolchildren Floyd is the only Floyd she knows.

“He just lights up a room everywhere he goes,” Bernice said. “He’s always been that way. I remember when he was just a baby, always dancing and happy. He always loved playing basketball and making people around him happy, at least he’s that way with his family. It hurts him when people say mean things about him. Some people say money and success changes you. Not him. He’s still the same to me.”

There are those who would argue that point. Perhaps it’s a sense of narcissistic entitlement that causes him to bypass the HBO prefight meetings, a tacit obligation the cable giant expects from every fighter who appears on the network. Mayweather has blown off the HBO broadcast team for both the Juan Manuel Marquez and Mosley fights, according to many sources. The only other fighters who have done that in the last decade were Naseem Hamed and a prime Roy Jones Jr.

Yes, the “Money” personality’s dominance over the Little Floyd personality is palpable. He’s a high-maintenance personality who doesn’t like to be challenged or told what to do.

“Floyd’s a bit of a control freak who wants to control everything inside and outside the ring, I’ll put it that way,” HBO analyst Larry Merchant said. “Public figures are pretty savvy when it comes time to manipulate the public to root for or against them. Floyd’s been able to do that and make as much money as possible. There’s no question that he calculates some of that, and he wants to be provocative and projects himself as arrogant and self-absorbed. I said one time that he’s a self-made man who worships his creator – him.

“The one thing I do have to say is what Floyd has pulled off – the ability to be a major star using a defensive style – is pretty remarkable. He wants to be great, and I have no problem with that. No one questions his ability or commitment. It’s just very unusual for a pure boxer who generally sucks the drama out of fights by the way he fights and winning the way he does, to continue being an attraction.”

Mayweather has become an attraction because he fits the personality profile for which the reality-TV world clamors. No one was more adroit at marketing himself than Muhammad Ali, copying the theatrics template laid down by wrestler Gorgeous George. But “The Greatest” usually (though not always) did it in a jovial, teasing manner. With Mayweather, it’s different. He’s funny to Team Mayweather but hardly a barrel of laughs to anyone else. He’s been known to throw tantrums.

Perhaps no one has brought out that side of Mayweather more during the last five years than ESPN’s Brian Kenny. If there is a modern Ali-Howard Cosell pairing, it’s been the Mayweather-Kenny combination. Some of their exchanges have been terse while others have been humorous.

“I think most people would be surprised that after our verbal sparring sessions, he’s usually happy in the end,” Kenny said. “I’ve seen all sides of him on and off camera. I’ve seen him be friendly more often than surly, though. I know he plays up being a thug, but that’s not his nature. I really do think he’s genuinely a good guy, even when we were sort of at odds with each other.”

One of Kenny’s best recollections of Little Floyd came moments after Mayweather had smacked around the smaller Marquez. As a prelude, the two had had a series of interviews in which they traded by verbal jabs, and Kenny honestly didn’t know what to expect when Mayweather climbed up the steps of the makeshift ESPN stage after the Marquez fight.

The reception Kenny received caught him off guard. Mayweather extended his arms to his TV antagonist giving Kenny a hug, whispering into Kenny’s ear, “Let’s show everybody we’re OK, and God bless you and your family.”

“Floyd has that side,” Kenny said. “The shame of it is that sometimes when we’re having a good time and getting along on the air, it doesn’t get as much air time. People want to see fireworks from him. It plays better on the air when he’s defiant and surly, they show those clips more frequently, but I don’t think that’s really who he is.”

Mayweather himself might not know where Little Floyd ends and Money begins. Why doesn’t he mend the schism between his superstar persona and who he really is – if Little Floyd is who he is?

“I don’t know why,” Mayweather said. “I have people tell me all of the time that I’m a lot nicer in person than the guy they see on TV hollering and yelling he’s better than Ali and Sugar Ray Robinson. I think Money and Little Floyd have a lot in common. They both want to be great, only Money lets the world know, where Little Floyd, you can say, knows he’s great.

“If I act like myself all of the time, do you think people would go out of their way to see me? People like to see the good guy win, not the bad guy. I like being the bad guy, though I know behind closed doors with my family, I know I’m the good guy.”

What will happen if Mayweather decides to dial down the boorish Money May, if he grows weary of acting like a petulant child? Look at Ice Cube, who went from a stone-cold street rapper to an avuncular figure in the TV sitcom Are We There Yet? Can Mayweather make that kind of transformation?

“Floyd’s trying to say that his Money image is just an act, but I knew Little Floyd since he was an amateur and he was respectful then,” said Naazim Richardson, who trains Mosley and also is a well-respected trainer on the amateur circuit. “He’s trying to say it’s an act, but that’s actually who he’s become. He sees how the public is responding to him. He can’t ease out of who he is in fear of losing street cred; he has to ease out slowly. He’s maturing and growing up.

“He still has a loyalty to the hood, but there’s going to be a time when he has to try to balance and please everyone.”

An anecdote that might reflect the competing sides of Mayweather came at ringside during a fight that didn’t even involve him. Mayweather was cheering on his friend Maurice Harris against Fres Oquendo in 2003 at UNLV’s Thomas & Mack Center. Money Mayweather was in full froth, calling Oquendo a bum and screaming advice to Harris, who obviously couldn’t hear him. As the fight progressed and Mayweather continued to verbally attacking Oquendo, who was winning the fight, someone behind Mayweather teasingly yelled: “If Oquendo is such a bum, Floyd, what does that make your pal Harris?” Mayweather wheeled around in his chair and began screaming in the fan’s face when a taller, older gentleman sitting next to the fan intervened, graciously putting his long arm between the two, only to have Money May slap it away.

“Who are you, what do you know, who are you?” Money demanded! Someone seated next to Mayweather tapped him on the shoulder and pointed up to one of the retired UNLV numbers hanging from the Thomas & Mack Center rafters – the one that said Reggie Theus. When Mayweather saw that, he made a 180-degree about-face and melted. By the end of the night, Mayweather interacted with Theus as if they were lifelong buddies.

Emanuel Steward, who has also known Mayweather throughout his amateur and professional career, still sees glimmers of Little Floyd. Steward remembers the time when Ali wasn’t so playful and when horrible things spilled out of his mouth in the late-1960s and early-’70s, especially involving Joe Frazier. Ali eventually overcame the original public persona he created to sell himself. Steward believes Mayweather can do the same.

“The character can take over the fighter anytime he says a lot, and Floyd certainly says a lot of things, so you start to believe it,” the Hall of Fame trainer said. “I still see the little boy side of him, that part of him is still inside. I think we’re still going to see a public change in Floyd Mayweather. As a matter of fact, I’d bet on it.”

Joe Santoliquito is Managing Editor of THE RING magazine