Oscar vs. Tito: Round 13 begins now

When you think of modern boxing rivalries, you typically think of opponents who squared off multiple times in thrilling action fights: Marco Antonio Barrera and Erik Morales. Israel Vazquez and Rafael Marquez. Manny Pacquiao and Juan Manuel Marquez.

You might be less inclined to think of opponents who fought one time and produced one of the most disappointing clashes in pay-per-view history.

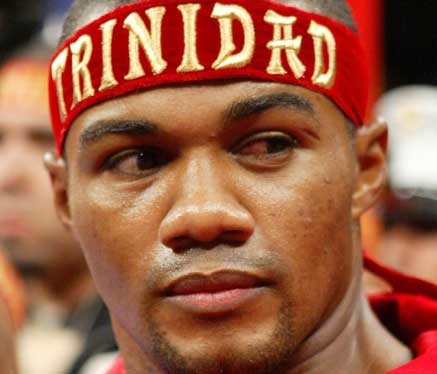

Nevertheless, Oscar De La Hoya and Felix Trinidad appear destined to go down in the books as each other’s chief rivals. There are several reasons for this.

First, they engaged in one of the highest-profile fights of all-time and its inconclusiveness and controversy remain a topic of discussion a decade later.

Second, they were born 25 days apart and rose to superstardom more or less simultaneously.

Third, their abilities and accomplishments were comparable enough that boxing observers can and will engage in an eternal debate over who was the superior pugilist.

And fourth, neither man really had another true rival. Trinidad didn’t have a single pro opponent he fought twice. And De La Hoya only had two: Julio Cesar Chavez (too one-sided to be a rivalry) and Shane Mosley (too friendly to be a rivalry).

Looking at it purely in a pound-for-pound senseÔÇöin other words, ignoring external factors like fame and marketability, where De La Hoya has an obvious edgeÔÇöthere are some contemporaries who clearly rank above De La Hoya and Trinidad and others who clearly rank below them. Bernard Hopkins, Pernell Whitaker, Chavez and Roy Jones fall into the former category. Fernando Vargas, Ike Quartey and Hector Camacho fall into the latter.

But it’s considerably more complicated to determine where “The Golden Boy” and “Tito” rank relative to each other.

In 2002, THE RING, in celebrating its 80th anniversary, ranked the 80 best fighters of the last 80 years, and Trinidad, at number 51, came in comfortably ahead of the 75th-ranked De La Hoya. But that serves to illustrate why it’s impossible to discuss all-time placement before a fighter’s career is over (which is precisely why I didn’t list fighters like Mosley, Floyd Mayweather Jr., Winky Wright or Manny Pacquiao in either the “above” or “below” categories two paragraphs ago).

Since those 80th anniversary rankings were compiled seven years ago, De La Hoya scored a career-defining win over Vargas, suffered some damaging defeats and remained a major-fight fixture; Trinidad was much less relevant, retiring and un-retiring twice and suffering a couple of defeats of his own without adding much in the way of wins.

With De La Hoya’s retirement announcement last week, it’s highly likely that neither future Hall of Famer will ever box again. And that means the time has come to try to determine who ranks higher on the all-time pound-for-pound list, De La Hoya or Trinidad.

For the purposes of this article, RINGTV.com spoke with three boxing insiders: veteran manager/promoter Mike Acri, veteran trainer Kenny Adams and Hall of Famer “Sweet Pea” Whitaker, one of the seven men to have faced both De La Hoya and Trinidad. Acri sided with Trinidad, Adams picked De La Hoya and Whitaker couldn’t choose one over the other.

Sure, it’s only a sample set of three, but the point is clear: This isn’t going to be easy.

What follows is a 10-category analysis that will hopefully lead us toward an answer:

1. Head-To-Head

The obvious place to start is with the Sept. 18, 1999 fight in which De La Hoya put on a boxing clinic for the first eight or nine rounds then tried to run his way to a victory. The judges gave Trinidad a majority decision. Most fans and media members thought De La Hoya prevailed by a point or two. Indeed, Acri, Adams and I all had De La Hoya winning narrowly. (Believe it or not, Whitaker has never seen the fight.)

Had it been a 15-rounder, maybe Oscar wouldn’t have finished the fight on his feet, but this was a 12-rounder, and unmanly as De La Hoya’s strategy was, there aren’t many people other than Jerry Roth and Bob Logist who gave Trinidad better than a draw. So while the official decision in the record books favors the Puerto Rican icon, our eyes and minds tell us De La Hoya was superior that night.

Edge: De La Hoya

2. Common opponents

Both Trinidad and De La Hoya dominated Camacho and won on points, they both stopped Carr, Campas, Vargas and Mayorga, they both got knocked out by Hopkins and they both won decisions over Whitaker. De La Hoya’s victory over the slick lefty, however, was highly debatable, whereas Trinidad won clearly. But Whitaker wasn’t as impressed with Trinidad as you might think he would be after Tito shattered all previous CompuBox records for fighters facing the elusive Sweet Pea.

“You gotta remember, I fought six rounds with a broken jaw and the fight was still close for the whole 12 rounds,” Whitaker said. “That’s the only fight I was in where you could give it to the other guy, but it was still close.

“Look, they were both good fighters, I don’t have anything bad to say about nobody. But I know I’m ranked ahead of both of them, I’ll tell you that much.”

Nobody’s debating that, Pernell. The debate here is between Oscar and Tito, and when it comes to common opponents, this is the key stat: In six of the seven cases, Trinidad faced the opponent when he was younger and better. Trinidad pinned the first losses of their careers on Carr, Campas and Vargas. The results were comparableÔÇöDe La Hoya and Trinidad both went 6-1 (4) against this crewÔÇöbut Trinidad’s wins carried more weight.

Edge: Trinidad

3. Pure Numerical Record

We’ll get into quality of opposition shortly, but the pure numbers, regardless of opposition, do matter, otherwise we wouldn’t still be talking about Rocky Marciano’s 49-0 record or Archie Moore’s 141 knockouts a half-century later.

In this comparison, it’s pretty easy: Trinidad went 42-3 (35), De La Hoya ended up 39-6 (30). They had the same number of fights, and Trinidad finished three up in the win column.

Edge: Trinidad

4. Boxing Skills

To call Trinidad “one-dimensional” is certainly an overstatementÔÇöhe was not some unskilled, Mayorga-esque plodderÔÇöbut against opponents with truly elite, pound-for-pound-level skills and ring smarts (De La Hoya, Hopkins, Wright) he did end up getting toyed with. Tito could box (see the Whitaker fight), just not as well as a handful of his best opponents could.

It doesn’t take much explanation to communicate why this category goes to De La Hoya. Yes, he largely lacked a ring identity, but in a way that speaks to his level of skill: He was so versatile that he wasn’t quite sure who to be once the bell rang. In terms of a jab, in terms of movement, in terms of defense, there’s simply no comparison between Oscar and Tito.

Edge: De La Hoya

5. Punching Power.

If you do believe Trinidad was “one-dimensional,” well, it was a hell of a dimension. When THE RING compiled a list of the 100 greatest punchers of all-time in 2003, Trinidad came in at No. 30. De La Hoya, despite being quite a knockout artist in his absolute prime at 135 pounds, didn’t crack the Top 100.

“Trinidad, at his peak, was just a little better, and I base that on the fact that he was a better puncher,” said Acri. “Even though I thought De La Hoya won their fight, to me it was a styles-make-fights thing. I thought Trinidad was better at his peak.”

Edge: Trinidad

6. Title Resume

The mainstream media’s blind recognition of any three-letter title as a “world championship” helped perpetuate this ridiculous designation of De La Hoya as a “10-time world champion,” but we all know better. If real world titles are like Academy Awards, then the straps Oscar won at 130 pounds and 160 pounds carried the significance of a People’s Choice award.

But De La Hoya’s reigns at 135, 140, 147 and 154 pounds all carried some degree of lineal legitimacy. And even if “four-division world champion” doesn’t sound as good as “six-division, 10-time world champion,” it has the advantage of being a number grounded in reality. And four divisions is still pretty amazing.

Trinidad only had meaningful reigns in two divisions, welterweight and junior middle, plus a second-rate reign at middleweight by virtue of beating William Joppy. What he has that De La Hoya didn’t was a reign of record-setting length on his resume. Though it was just an alphabet title and not an undisputed title until the very end of the reign, Trinidad had the longest uninterrupted reign in welterweight history at nearly seven years and 15 defenses.

This is a close one, but in the end, I lean toward De La Hoya’s success across so many divisions.

Edge: De La Hoya

7. Hall of Famers Fought

“Trinidad fought quality opponents,” Adams said, “but nobody in this era fought more quality opponents than De La Hoya.”

Indeed, De La Hoya had nine fights against seven opponents who either are in or will someday be in the Hall of Fame: Pacquiao, Mayweather, Hopkins, Mosley (twice), Trinidad, Whitaker and Chavez (twice). Trinidad had five fights against five Hall of Famers: Jones, Wright, Hopkins, De La Hoya and Whitaker.

“De La Hoya was one of the best marketed and best matched fighters in the modern era,” observed Acri. “It’s not just the money – he fought the best, he didn’t duck anybody. He fought some guys like Whitaker and Camacho and Chavez after their primes, but that’s about the only bad thing you can say.”

Edge: De La Hoya

8. Record Against Hall of Famers

Illustrating why neither Trinidad nor De La Hoya should crack anyone’s all-time pound-for-pound Top 50, they both posted losing records against Hall of Fame opposition.

Trinidad won his first two such fights, then dropped three straight (including two fights that wouldn’t have happened if he’d stayed retired after getting out at the perfect time initially). So his mark was 2-3.

Oscar’s was a decidedly uglier 3-6. His reputation for losing all of his big fights is borne out of short-term memory, since he won his share of fights in the ’90s that many experts picked him to lose. But as his career went on, he definitely morphed into a fighter who couldn’t win the big one.

“That loss to Pacquiao really hurts De La Hoya, it was just so terrible,” Adams said. “I knew that was going to happen because I was training [Edwin] Valero and he was in camp sparring with Oscar and I saw that he just wasn’t going to do well. Not just sparring against Valero; against other sparring partners too, he just wasn’t up to the task. Guys that basically would not touch him in his prime were giving him a lot of problems. So I saw that loss coming. But most of the general public was expecting Oscar to dominate Pacquiao, and the fact that he got dominated looks really bad.”

Yes, the numbers would look very different if De La Hoya had gotten the decision over Trinidad. He’d be 4-5 against Hall of Famers, and the Puerto Rican would be 1-4. But I already overruled the result of that fight once, in category number one. In this category, it’s only fair to let it stand.

Edge: Trinidad

9. Longevity

Even though he lost quite a few fights this decade and looked awful in his final bout, this category is a definite win for De La Hoya. He knocked out Vargas in ’02, still looked like a Top 10 pound-for-pounder in losing a disputed decision to a juiced-up Mosley in ’03, and was perfectly competent for eight rounds against Hopkins in ’04 and for most of 12 rounds against Mayweather in ’07. He not only remained relevant while Trinidad was in and out of retirement; he remained a Top 20 pound-for-pound fighter until his final fight.

After turning 30, all Trinidad did was beat Mayorga (looking good against an opponent who specializes in making top fighters look that way), get shut out by Wright and cash a paycheck against Jones. Tito was something special for a long time, from 1993 to 2001, but Oscar clearly outlasted him.

As for the impact of their late-career defeats, we have to be careful not to overemphasize that, as nearly all of the greats embarrass themselves a time or two before it’s over.

“It’s not like you’re in a rock band, like you’re U2 or the Rolling Stones and you can get better and put out an album that matters after you’re older,” Acri said. “For a boxer, there’s a time limit, and after you start to fade, the losses don’t count against your legacy so much. Your legacy is mostly determined already.”

Edge: De La Hoya

10. Pound-For-Pound Peak

Depending on whom you ask, there may have been times in their careers when De La Hoya and Trinidad each reached the No. 1 pound-for-pound position.

For De La Hoya, it was from the moment Roy Jones lost to Montell Griffin in ’97 until his late-rounds scamper against Trinidad in ’99. For Trinidad, it was from the end of ’00, after he beat Vargas and until he lost to Hopkins the next year.

But I, for one, never really thought the argument for Trinidad was all that legit. When he was peaking on pound-for-pound lists, Mosley was my clear No. 1, especially since he had just done what Trinidad couldn’t: beat Oscar controversy-free. As devastating as Trinidad looked against David Reid, Vargas and Joppy, it just so happened that Mosley looked like an almost perfect fighting machine at that same time.

Putting De La Hoya at No. 1 from ’97 through ’99 was questionable, too, since Jones was almost definitely the better fighter, but Jones did lose to Griffin and it made a lot of sense to remove him, at least temporarily, from the No. 1 spot.

In reality, probably both Trinidad and De La Hoya should have spent their prime years hovering around No. 2 or 3. But if we have to split hairs here and pick a winner, it’s the guy who was recognized by THE RING as the pound-for-pound king for a little while.

Edge: De La Hoya

So in the end, the score is 6-4 for De La Hoya. It’s not exactly scientific – maybe there should be additional categories, maybe some categories should be weighted more heavily than others – but it’s something to work off of. The fact is, De La Hoya will be remembered as the defining non-heavyweight fighter of this era, but that’s largely because of his image and the money he made. Based purely on what they did in the ring, he and Trinidad deserve to be remembered in the same sentence.

All that my analysis says is that De La Hoya should have his name spoken first in that sentence.

RASKIN’S RANTS

ÔÇó So, is everyone enjoying Roach-Mayweather 24/7?

ÔÇó Speaking of 24/7, it was interesting to learn this week that Floyd Sr. isn’t the only trainer on the show who used to have a creepy mullet.

ÔÇó In my interview with Kenny Adams, he mentioned that after his fighter, Deandre Latimore, beats Cory Spinks next weekend (Adams’ confident words, not mine), Latimore will be ready for anyone in the junior middleweight division. So I threw out a few names, and when I mentioned Paul Williams, Adams threw on the brakes. “He’s an octopus, man,” Adams said. From now on, when a fighter in the 147-to-160-pound weight classes says he’ll fight anyone, just go ahead and assume there’s an asterisk next to that claim on account of Williams.

ÔÇó Sorry, but I just can’t get excited for Floyd Mayweather Jr.-Juan Manuel Marquez. Mayweather-Pacquiao is the fight, plain and simple. And if Pacquiao loses to Ricky Hatton, then Mayweather-Mosley is the fight.

ÔÇó I was trying to count up all of the WBA “champions” in the sport, and then it occurred to me: Why don’t I save myself time and just count all of the professional fighters in the world who aren’t WBA titlists? Seriously, if there’s ever been a positive sign indicating that the alphabets are losing their grip on fighters, it was Yuriorkis Gamboa winning his 100-percent bogus belt on Friday night and reacting with all the emotion of a pitcher closing out a blowout baseball game in mid-April.

ÔÇó I don’t know Selcuk Aydin personally ÔǪ so why is it that I feel I can state with absolute certainty that the guy is a total a–hole?