Canelo Alvarez: The different one

CANELO ALVAREZ DEMONSTRATED EARLY AND OFTEN THAT HE WAS NO ORDINARY FIGHTER

(This story originally appeared in the November 2017 issue of THE RING Magazine)

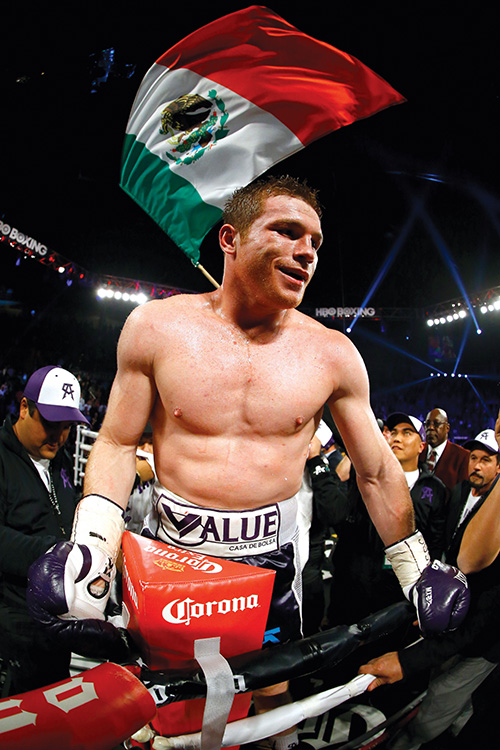

Once he rode the bus to work. Now he arrives in private planes and Cadillac Escalades. In 10 years, much has changed for Saul “Canelo” Alvarez but one thing has not: Rich or poor, he has always remained a fighter.

Not a rock star, although he is often treated like one. Not a politician, although he is more popular in fractured Mexico than El Presidente himself. Always he has understood what he is. He is a boxeador profesional.

Canelo Alvarez is not someone lost in a fractured identity crisis. He is at 27 what he was at 11, when he first visited a boxing gym with his brother Rigoberto. He is at 27 what he was at 15, when he left school and his father’s ice cream shop to enter the sometimes sordid but often splendid world of prizefighting.

Canelo Alvarez is a fighter, as Gennady Golovkin is about to find out. Whether he is a good enough one to beat the undefeated, unified middleweight titleholder in only his second full-fledged foray into the 160-pound weight class will be decided on September 16 in Las Vegas. For now, as he prepares for his greatest challenge, it is enough that he remembers the boy who used to ride that bus for an hour to get from his family’s sweltering cement block home in Juanacatlan, Mexico, to the gym of Eddy Reynoso and his father, Jose “Chepo” Reynoso, in Guadalajara. Remembers the hunger in that boy’s belly to show the world he was not just a pale-skinned, redheaded novelty, not just another Mexican kid dreaming of being the next Chavez.

Photo by Kathy Willens /AP

Boxing is most often a nightmare for dreamers. It is the loneliest job in sports. To seek it is to embark on a hard road to glory. Trainers can help you. Promoters can hype you. Writers can glorify you. But when the bell rings, you stand – or fall – alone.

Canelo has always understood and accepted this. It is part of boxing’s dark allure. In the ring you are on your own, left to face a menacing opponent with mayhem on his mind. Nothing can help you but fury in your fists and calmness in your mind in the face of looming chaos.

If you can learn to function in the midst of such bedlam – fists and hangers-on coming at you with equally dangerous intentions – boxing becomes a simple endeavor. Kill or be killed. Yet in other ways, as Canelo learned four years ago when tasting the only loss of his career, it can be a decidedly more complicated exercise.

Floyd Mayweather Jr. taught him that lesson by baffling him more than beating him, controlling both the pre-fight hysteria that surrounds a multi-million dollar boxing event and the fight itself. That night Mayweather won a majority decision from a then 23-year-old Canelo more with his mind than his muscle. In Canelo’s world, it was more like a pillow fight than an exercise in bruising, but when it was over his hand was not raised for the first time in nearly a decade.

Canelo, it is said, learned much during that encounter. Learned things that have made all the time spent promoting the Golovkin fight easier to handle. Who knew the kid riding that bus day after day would one morning be led into a room stacked with 1,200 pairs of boxing gloves and told he must sign them all. What gym prepares you for that?

Who knew how tedious and mind-bending all the interviews and photo shoots and press conferences can become, your opponent’s face either literally or figuratively always in your own? Who could understand the difficulty of maintaining focus on the only thing that counts – preparing for your opponent – when every day there is a new distraction, another person pulling at you?

There is no escape from The Big Fight until it is over. It is like a patient assassin, constantly stalking you, never letting you relax or escape from its ominous shadow. Dark of night or first light of dawn it is there, never letting you forget, “I’m coming for YOU!”

That is a difficult situation to confront at any age, but then so was a decision to fight your way out of Juanacatlan. Difficult but not impossible if you have The Gift.

Alvarez stopped British veteran Ryan Rhodes to retain his WBC belt in 2011. (Photo by Archivo Agencia EL UNIVERSAL)

THE BEGINNING

Canelo Alvarez was always The Different One.

Youngest of eight children, seven of them boys, Canelo – “Cinnamon” – did not look like the rest. He alone bore the red hair and light complexion of his mother, Ana Maria. People noticed and they laughed.

He also seemed to lack the fighting spirit of a family of boxers. As a youngster, kids picked on him, taunting him about his red hair and freckled face. He didn’t fight back. People noticed and they laughed.

Then one day, according to the family history, the dam broke. A much larger boy who had spent many days tormenting Canelo spoke up once too often. Suddenly the tiny redhead was all over him, bashing him in the face, bloodying his nose, learning for the first time he had what his brothers did not. He had a gift for mayhem.

At 11, Canelo followed Rigoberto to the Julian Magdaleno Gym. That’s where he found the Reynosos, who became his lifelong trainers and mentors. In a sense they are his creators. They would build the boy into a boxeador. But el campeon del mundo? The champion of the world? Who but a boy can dream such things?

The Reynosos initially thought only of training this one like all the rest. Teach him the fundamentals. Balance. Leverage. How to throw a hook with bad intentions. Teach him. Then we’ll see what we’ve got.

In three years they had plenty. Canelo had a 44-2 amateur record and had won Mexico’s junior national championship at 14. He’d also convinced other trainers to keep their kids away from the red-headed boy with the thick jaw. The boy who once would not fight now could not find anyone to fight.

‘My fans know I started from nothing,

from the bottom up. From zero.’– Canelo Alvarez

Because of that, he turned pro at 15 and, depending on whom you believe, either won 10 of his first 11 fights by knockout or 20 of his first 21, the latter 10 the Reynosos claim having taken place off the books in small Mexican venues where records are not kept and cops are avoided.

About the same time, his parents divorced and the large family was subdivided. Canelo ended up with his mother but at one point there was a family reunion of sorts. On June 28, 2008, Canelo and his brothers set an unusual record when all seven of them fought on the same card. Three were making their pro debuts and lost. Canelo did not.

One story Chepo Reynoso loves to recall as an illustration of who Canelo was becoming is a night his teenaged fighter was matched against an older, bigger and heavily tattooed opponent. Reynoso was concerned. He expressed this to Canelo.

Reynoso told him he was worried not only because of the size difference but because he knew little about the opponent. Then the bell sounded and not long after it tolled Canelo dropped the man with a fierce body shot that would become his trademark punch.

After the referee counted the guy out, the teenager returned to his corner and told his old trainer, “There’s your fucking worry.”

Soon after that a decision was made: It was time to call Oscar De La Hoya.

THE RISE

“Chepo is from my parents’ hometown,” Golden Boy Promotions president and chief matchmaker Eric Gomez recalls when asked about the first time he heard of Canelo Alvarez. “I always ask the guys we work with to keep us in mind if they have a kid coming along.

“It’s the same conversation with every trainer and manager. Everybody has the next Oscar. The next Pacquiao. The next Floyd. You listen but you don’t know.”

When Reynoso contacted him about Canelo, Gomez asked for a video. The fighter was only 14 at the time but there was something there that caught Gomez’s eye.

He went to Mexico to watch him spar with former champions Javier Jauregui and Oscar Larios, two fighters the Reynosos also trained. What he saw impressed him.

“He was holding his own with them,” Gomez said. “Every time I’d go see him spar, he was getting better.”

But he noticed something more. He noticed the body-punching and also an unusual patience not often seen in young fighters. He fought with fire but also with calm attention.

A 20-year-old Alvarez (left) faces off with Matthew Hatton. (Photo by Jae C. Hong / AP)

“It is a virtue that I have,” Canelo said of his demeanor inside the ring and out. “It’s the confidence that the hard work has been done. People expect me to go for the knockout but I never go for it. If it comes, it comes.”

As time passed, Canelo continued to win and was soon a staple of Televisa, the massive Mexican broadcasting conglomerate that is beamed into the majority of Mexican homes. He was becoming a star.

Although he had not yet signed him, De La Hoya agreed to put Canelo on a Golden Boy show in California against a skilled journeyman named Larry Mosley in 2008. It was a test.

“Larry was no pushover,” Gomez said. “He’d been a good amateur and he was a good pro. Canelo wasn’t that impressive that night but he found a way to win. We didn’t sign him immediately but we kept watching him.”

Three fights later, in Zapopan, Mexico, Gomez matched Canelo against undefeated Euri Gonzalez. Gomez knew Gonzalez had fast hands and testing power. It was a pop quiz, literally, and Canelo passed – but not without a moment of high tension.

“Canelo got hit with a big right hand along the ropes halfway through the fight,” Gomez said. “He got hurt but he came back and stopped him in the 11th round. That’s the night we thought we had something special.”

Canelo fought eight more times, mostly in Mexico, before De La Hoya signed him to a promotional deal in 2010 and quickly tested him against former world champion Carlos Baldomir. Baldomir was verbally insulting to his young opponent, dismissing him as another kid who had chosen the wrong business.

Canelo said little in public but privately seethed. That night he exploded the way he had when that kid taunted him one time too many, dropping Baldomir late in the sixth round with a hard left hook. Dazed and unable to clear his head, Baldomir was counted out by referee Jose Cobian. It was the first time in 16 years he’d been stopped.

“Baldomir was a risky fight but I’d seen things that made us confident he could outbox him,” Gomez said. “He did more than we expected.”

Hadn’t he always?

Seven months later he would become the youngest junior middleweight titleholder in history when he outpointed Matthew Hatton – the brother of Ricky – for the vacant WBC belt. By then his brother Rigoberto had briefly held the “interim” WBA junior middleweight title, losing it in his first defense to Austin Trout.

Canelo would avenge that loss 26 months later when he ignored De La Hoya’s advice and accepted a bout with the confounding Trout, a master boxer slicker than motor oil, against whom it was difficult to look good. Canelo dropped him in the seventh round and won a unanimous decision. It seemed it would be left to the youngest of the fighting Alvarez brothers to make the deepest mark in boxing. He was the one who had the magic.

“I was against that fight,” said longtime California promoter and matchmaker Don Chargin, who serves as a consigliere on boxing matters for De La Hoya and Gomez. “I liked Canelo from the first time I saw him. He was one of those old-school Mexican fighters. He threw the hook to the liver like it was born in him.

“But I always hated to see a guy who makes good fights in with guys with that awful defensive style like Trout and (Erislandy) Lara (whom Canelo would outpoint two fights after losing to Mayweather). Canelo didn’t care. The great fighters want to fight everybody. That’s him.

“In the end he was right and I was wrong,” Chargin continued. “He showed in those fights he was able to adapt. He was still a great body-puncher but his combinations were improving. They had more quickness and snap. His confidence was growing.”

So, too, was his popularity. He was by then the most popular fighter in Mexico and not even being outboxed by Mayweather could derail him.

Some close to Alvarez didn’t want him to fight Erislandy Lara (right), but things worked out. (Photo by Josh Hedges / Getty Images)

“I felt Canelo was ready for the Floyd fight,” Gomez said. “I thought he was too big and too strong. I thought he would overwhelm him. Oscar felt he wasn’t ready yet. He thought he was too young, but their coaches convinced Oscar and I agreed.

“If you’re a baseball player, you want to play the Yankees and the Dodgers. This was the same way. You had to let him do it.

“Ultimately we were wrong and Oscar was right, but my mindset was Floyd was not going to be able to hurt Canelo. The only way he could win was by running, so you look at the risk and you see it, but the reward was huge and the risk was not. So we took it.

“Yes, Canelo lost a majority decision but he came out of that fight bigger than ever. More popular in Mexico. And now he was popular in the U.S. too.”

KING OF THE BOX OFFICE

Four fights after Mayweather, Canelo faced RING, lineal and WBC middleweight titleholder Miguel Cotto at a catchweight of 155 pounds. Cotto was content with that and Canelo had not yet grown physically into the full-fledged middleweight he believes he will be when he faces Golovkin in September. It was another test against a rugged opponent a shade past his prime at 35 but still dangerous.

Surprisingly, Cotto stayed on his toes most of the fight as Canelo punched his way to a unanimous decision by wide margins on the scorecards – but not so in the minds of some, including Cotto. In the end, that didn’t matter. Canelo, who still holds the RING championship, had completed a long journey from the boy on the bus to a boxer on the mountaintop.

By defeating Miguel Cotto, Alvarez seized the middleweight championship. (Photo by Al Bello/Getty Images)

“We’re very proud of Canelo today,” trainer Eddy Reynoso said at the time. “As we all know, he started from the bottom and now he’s the champion. I was never worried about him from the first round through to the 12th round.”

Although there was a clamor to face Golovkin next, his handlers knew better. Although a star in Mexico, he was not yet a full-blown pay-per-view phenomenon in the U.S. and frankly neither was Golovkin, who was knocking out second-line fighters with regularity but never getting the chance to face the kind of opponent who can define an elite boxer’s career.

“Canelo was struggling a little more than usual to make 154 but he wasn’t a full-fledged middleweight yet,” Gomez said. “We felt all along he would be, but we let his body grow and develop naturally into being a true middleweight. While he was doing it he was gaining experience. He was becoming a seasoned pro. He needed that.”

Six months after beating Cotto, Canelo blew away former junior welterweight titleholder Amir Khan, knocking him cold with a savage overhand right at 2:37 of the sixth round. Khan landed on his back and referee Kenny Bayless knew he didn’t need to count. The lights were out.

During his post-fight interview, Canelo invited Golovkin into the ring to address growing criticism that he was avoiding the Kazakhstani. “In Mexico,” he said, “we don’t fuck around. I don’t fear anyone.”

Now the talk grew more incessant to face Golovkin next, but Golden Boy made the decision to try and make history first. Canelo went back to 154 pounds to face WBO junior middleweight champion Liam Smith at AT&T Stadium, the massive home of the Dallas Cowboys, in search of a record live gate.

Smith was a relative unknown in the U.S. but it didn’t matter. By now, Canelo was a box-office success, a point he drove home by attracting a crowd of 51,240. Among them was Golovkin, who was one of the few who didn’t wince when Canelo stopped Smith with a body shot.

Now there was only one piece of business left before facing Golovkin, a bit of local business that would also allow Canelo to test himself above 160. He wanted one last local brawl for Mexican bragging rights.

For a number of years, Canelo and Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. battled to become Mexico’s most popular fighter. While most felt Canelo was superior, Chavez had both the weight of his father’s legacy as Mexico’s greatest fighter and his own heavy hands behind him.

Alvarez takes his stardom in stride at the New York stop of the Canelo-GGG promo tour. (Photo by Bebeto Matthews / AP)

Chavez would eventually win the WBC middleweight title but lose it and the respect of Canelo after a string of lackluster performances, training issues and weight problems. But Chavez was always spoiling for a fight with Alvarez and on May 6 he got it.

“He was testing his body at a new weight,” Gomez said. “It was also personal. He wanted to prove who was better.”

Canelo won every round on all three cards, patiently potshotting Chavez but never taking a foolish chance pursuing a knockout that wasn’t available because of Chavez’s cautious approach. A few minutes after it was over, Golovkin walked into the ring.

It was the first time anyone could remember a post-fight press conference that was really the kickoff press conference for the most anticipated showdown of the year. After Golovkin made his ring walk to the strains of “Seven Nation Army” by The White Stripes as smoke and flashing lights surrounded him, the two fighters sat in the middle of the ring wearing business suits, not boxing shorts, because that’s what this was. It was a final business meeting to announce Canelo Alvarez’s second chance to rule his sport and Golovkin’s first.

“My fans know I started from nothing, from the bottom up,” Canelo (49-1-1, 34 KO) said. “From zero. I’ve worked my way up with a lot of sweat and sacrifices. I’ve never feared anyone since I was 16 and fighting as a professional. When I was born, fear was gone. I never got my share of fear.”

No fear since the day he bloodied a bully’s nose in the street in Juanacatlan. Now that boy has his chance to remind the world he is more than just a boxeador profesional. He is what he dreamed of being on all those long bus rides. He is el campeon del mundo, just like his idol growing up, Julio Cesar Chavez Sr. And he intends to stay one.

“This is Canelo’s opportunity to be considered great,” Gomez said. “This is for boxing history. He wants to be a bigger star than Chavez.”

MORE CANELO-GGG FEATURES FROM THE RING:

Gennady Golovkin: The quiet man

Separate Paths: Do fighters with extensive amateur backgrounds (like Gennady Golovkin) have an advantage over those who don’t (like Canelo Alvarez)?

Ranking THE RING’s 31 middleweight champions

These articles first appeared in the November 2017 of THE RING Magazine. THE RING, boxing’s foremost publication since 1922, contains in-depth features and commentary from some of the sport’s top writers. You can get the digital edition of the magazine as part of our new Ringside Ticket package by subscribing here.