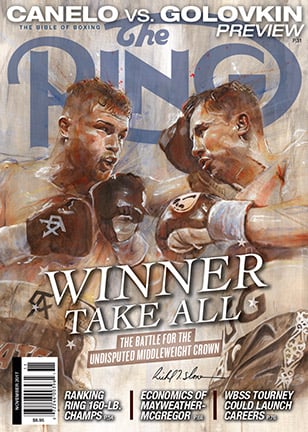

Gennady Golovkin: The quiet man

GENNADY GOLOVKIN IS A RETICENT, PEACEFUL PERSON. ‘GGG’ IS ANOTHER MATTER ENTIRELY.

(This story originally appeared in the November 2017 issue of THE RING Magazine)

The Summit Gym is in a piney mountain neighborhood with streets named after unremarkable birds, like Thrush and Wren. You expect you’ll know the gym when you see it. And then you will drive past it, probably more than once. The most combative thing about the white duplex with the spacious driveway is the “No trespassing” sign at the edge of the property.

Inside, you’ll pass under clusters of boxing gloves as if in a pugilistic orchard. The walls are papered with boxing images edge-to-edge. There’s a ring with its canvas well-seasoned by sweat, punching bags suspended by chains or trembling on floor-to-ceiling bungee cords, a stereo playing Russian pop duets, an indifferent department-store mannequin, and the literal architect of it all, Abel Sanchez.

Sanchez, who was born in Tijuana, Mexico, 61 years ago and brought to Los Angeles by his mother when he was 5, is always smiling in anticipation of the next sentence, whether it be yours or his (odds heavily in favor of his). Rapid-fire wisdom spills out of him, information is eagerly absorbed and the joy he clearly derives from his surroundings is consistent whether he is discussing his golf handicap or a liver punch. His love of silence is just as potent, though.

“Everybody here is quiet, everybody’s hard-working,” said Sanchez when I visited his facility in Big Bear Lake, California, 7,000 feet above where L.A. meets the sea a couple hours’ drive to the west. “Every gym has a persona, and this gym has the Golovkin persona.”

“Everybody here is quiet, everybody’s hard-working,” said Sanchez when I visited his facility in Big Bear Lake, California, 7,000 feet above where L.A. meets the sea a couple hours’ drive to the west. “Every gym has a persona, and this gym has the Golovkin persona.”

That persona’s namesake is everywhere you look. From murals and promotional posters to more intimate snapshots documenting a career’s worth of middleweight triumphs, the face of Gennady Golovkin does indeed define the space. But if Sanchez is a strange case of two strong personalities in the same body, then Golovkin is Jekyll and Hyde.

One photo in particular nails it. It’s the fighter in January 2013, in the ring at the Theater in Madison Square Garden seconds after winning a fight against Gabriel Rosado by seventh-round TKO. Astonishingly, Rosado remained on his feet until his corner threw in the towel that night, but the cost of his ordeal is splattered all over Golovkin’s face and shoulders. A director staging the fight might’ve told the make-up artist to scale back the blood for realism. And yet here is the victor, 12 fights into a knockout streak that would eventually reach 23 and earn him the titles of “most feared” and “most avoided” man in boxing, not reveling in gore, as one might assume a fighter once nicknamed “The God of War” would, but quietly saluting one quadrant of the arena with a simple kiss on his crimson-flecked glove. Perhaps even more unnerving than a primal scream is the calm.

“I don’t like fight. I understand fight,” said Golovkin in choppy English. He’s from Kazakhstan and speaks four languages, the others being Kazakh, Russian and German. “Nobody likes it, seriously. You like this face? No. You like broken hand? No.”

This is the allure of Golovkin, now popularly known as “GGG” (his initials, usually spoken as “Triple-G”). In conversation, he is serene and funny, his humility is sincere and his wide grin is charming. He unfailingly compliments his opponents, both before and after a fight, however long it lasts, but in between those two bells he’s like a nightmare you have after binge-watching “Shark Week.” His in-ring demeanor and punching power are scary enough that some have suggested his nickname should instead be “666.”

As Sanchez once heard Golovkin describe it: “When I’m talking to you outside the ring I’m Gennady Golovkin. When I step through the ropes I’m Triple-G.”

It’s the sort of quote that will probably soon be heard over slow-motion footage of him shadowboxing in front of a mirror, as HBO’s “24/7” crews have once again been mobilized to light the torches for the next superfight. On September 16 in Las Vegas, “Gennady Golovkin” will send “GGG” into what is surely the most important battle of “their” life: a middleweight championship fight against Canelo Alvarez. It’s the biggest puncher against the biggest star, millions to be made, issues to be settled, legacies to be forged.

But as dramatic as they are, slow-motion gazes and all, Golovkin says those storylines don’t get him out of bed in the morning.

For those of us ostensibly dedicated to finding the ones that do, there are bits about his past scattered online that point to the promised land. Hardship. Loss. All the reasons for what a fighter does and why he does it so vehemently. The inciting incidents of great boxing stories.

I’d read those stories before I drove up the mountain to interview Golovkin, and I went assuming I’d glimpsed the “why” more than the “what” of his career. I was thinking he’d probably even be pleased by a writer who wanted to get past “so how’s training going?” and dig into what really matters. This delighted me because I, like so many people, respect both versions of Golovkin.

A couple days later I was telling his promoter, Tom Loeffler, what happened next.

“Yeah …,” said Loeffler with a slow deadpan that suggested I wasn’t the first person to congratulate myself in advance. “Gennady doesn’t really like talking about his past.”

THE BEGINNING

Here’s what you can believe with reasonable confidence: Golovkin was born in 1982 in Karaganda, Kazakhstan, a country that was part of the Soviet Union at the time. His mother is Korean and his late father was Russian.

Golovkin describes his hometown as being “like Texas; everybody comes for oil,” except in Karaganda it was coal, which is what his dad pulled out of the ground for a living. Sanchez describes it as “like the worst part of Detroit. … Hard town.”

He wasn’t exaggerating. For a long time Karaganda was Russia’s depository for those it deemed to be criminals – a sort of Soviet Australia.

Golovkin had three brothers – a twin, Max, who also boxed and now works in his brother’s corner, and two who were older, Vadim and Sergey. The most sensationalist versions of Golovkin’s childhood read like pages from Johnny Tapia’s Mi Vida Loca biography, with his older brothers throwing him into human cockfights on the streets of Karaganda.

Bringing that up drew an annoyed, but patient response.

No, Golovkin said. His brothers took him to a local gym when he was around 8, 9 years old. In the gym, they began choosing opponents from the regulars.

“Everybody is tough, bigger than me, older than me. And (my brothers) used to go, ‘Him?’ And (I’d say), ‘Yeah, no problem.’” The streetfights would come a bit later, he said, after the Soviet Union collapsed in the early 1990s and a “very bad time for Kazakhstan” ensued. In those times, kids would fight over things like a nice pair of shoes.

Why did his brothers “promote” these gym scraps? Sanchez thinks it’s pretty simple: “They were 10 years older than him! You’re mean to your little brother!”

But it got Golovkin in the gym, and his reputation quickly grew.

“The thing was, he handled himself,” said Sanchez. “I’m sure the respect from the older guys was a lot because this little kid was kicking the shit out of them.”

When Gennady was still a child, Sergey and Vadim joined the army. Notifications of their deaths came back to his family four years apart. I asked about reports saying the Golovkins had never received any details from the government and referenced online stories using the word “battle,” and the annoyance edged closer to anger. Sanchez tried to lighten the mood by saying, “It’s like what Trump says: a lot of fake news.”

I dropped it there.

“Certainly it’s a backstory that could be used for sympathetic purposes,” said Loeffler. “I mean, HBO would love nothing more than to interview his mother or show his son and his wife (who don’t attend his fights). He says that’s his personal life and this is his business life. This is his job, to go in the ring and defend his world titles. So he doesn’t use that for personal gain, for getting sympathy from boxing fans.”

No, the sympathy has always been reserved for Golovkin’s opponents. In the amateurs, he reportedly had 350 fights and lost only five of them. (Some argue online that the second tally should be more like eight, thus lowering his win percentage from an overinflated 98.57 to a more human 97.71.) He was never down and never hurt, according to Sanchez.

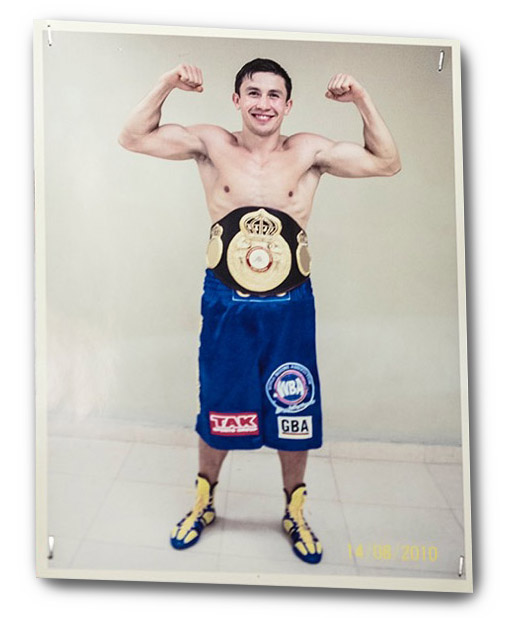

In 2003 he won the middleweight gold medal at the World Championships in Thailand, outpointing Matt Korobov and Andy Lee and knocking out Lucian Bute along the way. He then went to the 2004 Olympics in Athens, where he bested Andre Dirrell in the semifinals but then took silver after losing to Russia’s Gaydarbek Gaydarbekov on points.

Allegations that Kazakhstan’s gold medal count had been capped at one ahead of the games – and that Golovkin had been told it wasn’t reserved for him – have been published before. Golovkin shrugs it off as political.

Fix or not, it was a rough fight. Watch the video, and in his aggression you can see why he’d say his reputation in the gym was as a “crazy guy.” But you don’t get an amateur record like his just by mauling people. The balance, accuracy and power that would become hallmarks later are also there. Watch the right hook that plows through Gaydarbekov’s face and without losing any speed loops around and hits it again. It’s a beautiful thing.

THE RISE

Having been scouted by several promoters during his amateur career, Golovkin chose to sign with the German company Universum and made his pro debut in 2006 against a fighter with 22 losses and a single victory. But despite his rapid climb to the top of sanctioning-body rankings, his handlers focused their resources on moving middleweight titleholders Felix Sturm and Sebastian Zbik instead of him.

So, in 2010, after 18 wins and 15 knockouts against nobody of note, hungry for a title shot and already approaching 28 years of age, the frustrated fighter took matters into his own hands. He successfully sued to end his contract with Universum and then, having already started his own company, GGG Promotions, Golovkin took a trip to Southern California.

There he visited multiple gyms, including those run by established local trainers Freddie Roach and Robert Garcia, but felt comfortable at none of them until he found Sanchez in the seclusion of Big Bear.

There he visited multiple gyms, including those run by established local trainers Freddie Roach and Robert Garcia, but felt comfortable at none of them until he found Sanchez in the seclusion of Big Bear.

“I had no clue who he was when he got here,” said Sanchez. “When he walked in he looked like a damn choirboy. I thought, ‘He’s not a fighter.’”

But they clicked the first day.

Sanchez is a building contractor by trade (all those houses along Elliott’s suburban street in the movie E.T.? His work.) and was just getting back into training fighters after a long hiatus, but he’d already had one successful run. Despite having no gym of his own, he guided Lupe Aquino to a world title in 1987. He did the same with Terry Norris a few years later, and then again with Terry’s older brother Orlin.

Echoing Golovkin’s experiences in Karaganda, Sanchez’s own father had arranged fights in his front yard for his son and other kids in the neighborhood – not to be sadistic, he just figured they’d fight anyway so they might as well do it in a controlled setting and learn to handle themselves.

Control is a thing with Sanchez. He travels with his own scale, always has a backup version of everything, works on cuts himself, scoffs at nutritionists and has no assistants. If the equipment he needs doesn’t exist, he invents it. He has multiple top-of-the-line cameras and photographs his own fighters in his own studio (hence the mannequin, which he uses to position lights). Before the sponsorship deal with Nike, Sanchez used to paint Golovkin’s shoes with nail polish to match his trunks. He described himself as anal-retentive, and I agreed.

He also has a relentless competitive streak and a bruising work ethic. His fighters sometimes do 3,600 sit-ups in a day. They have no idea how far they’ll run when they wake up. Sanchez pushes them beyond routines into no-man’s land so the boundaries of actual prizefights seem quaint.

He also has a relentless competitive streak and a bruising work ethic. His fighters sometimes do 3,600 sit-ups in a day. They have no idea how far they’ll run when they wake up. Sanchez pushes them beyond routines into no-man’s land so the boundaries of actual prizefights seem quaint.

He began immediately with his new charge, tweaking Golovkin’s obvious talents to fine-tune a style that would appeal to American audiences. To develop GGG’s now-famous ring generalship, they watched videos of “cutting horses” trained to herd cattle. After nine months, Sanchez knew he had the best fighter he’d ever worked with.

Their first fight together was in Panama against Milton Nunez, whom Golovkin knocked out in the first round. After two more victories, they teamed up with Loeffler, who had launched his company, K2 Promotions, with heavyweight brothers Vitali and Wladimir Klitschko.

Golovkin’s debut with K2 was against Lajuan Simon in Germany – again, a first-round knockout – but Loeffler had his eye on American cable, so he began pushing his client hard. He soon encountered trouble, though: Nobody wanted to fight his guy.

“I told HBO and Showtime both … he doesn’t need a lot of money, he’ll fight anyone you put in front of him,” said Loeffler. “Literally they gave me a list of 20 guys and Gennady approved all of them. Andre Ward was on the list, Sergio Martinez was on the list, (Julio Cesar) Chavez Jr., (Kelly) Pavlik – all the guys were on the list.”

In 2012, the WBA ordered Sturm (whom Loeffler calls “the worst avoider”) to defend his title against Golovkin. HBO’s plan was for the winner to fight the winner of IBF titleholder Daniel Geale vs. Dmitry Pirog (who had recently knocked out Daniel Jacobs in a shocker) and unify the titles. According to Loeffler, Sturm instead exploited a loophole favoring unification fights and lured Geale to Germany by offering him $600,000 – significantly more than the $250,000 he’d get for Pirog.

That left Pirog for Golovkin, but then Pirog pulled out with an injury four weeks before the fight. Which is how Golovkin made his HBO debut knocking out an awkward southpaw named Grzegorz Proksa in five rounds.

The avoidance problem was just beginning, though. As was its unfortunate corollary: Golovkin wasn’t gaining experience against top-tier foes.

Golovkin’s next fight was Rosado, whom Loeffler credits for the willingness he showed. Those who followed – Nobuhiro Ishida (KO 3), Matthew Macklin (KO 3), Curtis Stevens (TKO 8), Osumanu Adama (TKO 7), Geale (TKO 3), Marco Antonio Rubio (KO 2) – were “the best guys who would step into the ring with him. We went out of our way to fight guys.”

Golovkin vs. Curtis Stevens, 2013 (Photo by Al Bello / Getty Images)

Despite Golovkin being “World” and then “Super World” WBA titleholder, Loeffler said they were still paying opponents equal money to get in the ring. It was only the guys with nothing to lose who would agree.

Because it wasn’t just that he was beating people — it was the way he was beating people. Completely dominating them. It was Mike Tyson-esque.

Golovkin’s heavy hands had been creating tremors in the SoCal gym scene as well. Sam Garcia, a young trainer based farther north in Salinas, California, who began bringing fighters to spar at The Summit in 2010, remembers well the two Golovkins:

“In the summer, he’ll be suntanning in front of Abel’s house – you know, swim trunks – and I’m barbecuing tri-tip for him. Just a cool dude. And then he gets in the ring and he’s a killer.”

Garcia was struck immediately by Golovkin’s quiet work ethic and how it rubbed off on everyone around him. He said he witnessed some of the things that had become local folklore: Golovkin forcing heavyweights to quit, fighters saying they’d never felt anything like his power. He even saw some of the most scrutinized sparring sessions of all, when a young man named Saul “Canelo” Alvarez came to Big Bear in 2011.

After acknowledging a slew of caveats – Canelo’s youth and inexperience, his smaller size and his still-developing confidence – Garcia said, “I know what I saw. I know a lot of people, they want to stay neutral … No. Golovkin destroyed Canelo in sparring. He was doing what he wanted, when he wanted to do it.”

Things had changed by 2015. Canelo had become the Ring Magazine middleweight champion by nearly shutting out Miguel Cotto, but this never sat well with some purists because the fight had taken place at a catchweight of 155 pounds, not the traditional 160-pound limit. His first defense, also at 155 pounds, was a frightening knockout of Amir Khan, who’d last fought at 147. Canelo wasn’t a real middleweight, critics said, and he was sitting on a title he didn’t deserve. And, specifically, they accused him of avoiding Golovkin.

And so the drumbeat for Canelo vs. GGG got steadily louder. After Khan had been restored to full consciousness, Canelo invited Golovkin into the ring and told him in graphic terms that he was not afraid – that no Mexican is afraid. As expected, that played well with Canelo’s massive fanbase of Mexican admirers.

But Garcia had also witnessed another phenomenon in the gym, one that would ultimately yield some irony. He said every time Golovkin sparred, the Mexican fighters, all of them bound to a tradition of uncompromising brawlers, would stop what they were doing and gather around the ring.

“You gotta watch this guy,” they’d say. “He’s what we want to be.”

WHAT REALLY MATTERS

After lunch at a local Mexican restaurant where Golovkin’s photo is the first thing you see upon entering, I was back at The Summit watching him shadowbox.

It was just him and me in the room and there was the clear sense that he was still annoyed by my presence. That, plus the discomfort from the earlier interview and the platter of carnitas in my stomach, was making me feel a bit unwell. Suddenly he stopped mid-punch and walked over to the ropes. It’s at that moment I realized that this man could destroy my entire skeleton with his bare hands.

“Let me ask you a question. Serious question.”

“OK,” I said.

“How long have you worked at Ring Magazine?”

I was relieved by how un-serious this question was. “About four years.”

And then Golovkin said, “Why does Ring hate me?”

I was blindsided. I blurted out what any desperate, panicked man says: “What? I love you!”

The Golovkin standing in front of me was a star. When he’d referred to Rosado in his post-fight interview by saying, “He is good boy,” the compliment was immediately converted into a catchphrase. When he spoke of the “big drama show” he wanted to deliver, people adopted that term as well. And not mockingly, either. This new, quirky Golovkin-speak was a language they wanted to hear. He was a fighter they wanted to watch.

The superfight had been sealed after Canelo eviscerated Chavez Jr. at a catchweight of 164.5 pounds. Golovkin had already picked up two more belts, the IBF with an eighth-round TKO of David Lemieux and an upgraded WBC version when Canelo vacated it to avoid what he perceived to be a premature clash. Golovkin’s apparent struggle in his last fight, a KO streak-breaking decision over Jacobs, had pushed the odds for this Mexican vs. “Mexican” fight into the vicinity of even.

Golovkin was a national hero in his country, on a level that hasn’t been seen since perhaps Manny Pacquiao at his peak. He was about to net millions of dollars – at least 20, by Loeffler’s reckoning. And a step closer to boxing’s highest distinction – greatness – was there for the taking.

All that … and he was upset that my employer didn’t recognize him as undisputed middleweight champion of the world, since Canelo still holds the Ring title.

He’s not the first to bring up the issue, of course, and he’s not the only one to object. I’m very familiar with passionate arguments on both sides and I have my own opinions. The shortest answer, whether you buy it or not, is lineage. Canelo beat Cotto, who beat Sergio Martinez, who beat Kelly Pavlik, etc. That’s how it works with the Ring belt — the man who beat the man who beat the man — but there are some who say that the laurel of a true division champion should be protected from things like fighters demanding a catchweight and that transgressors should be stripped accordingly.

But the question had never been posed so viscerally, and, once I had the two hours’ worth of road between me and The Summit, it produced a sort of clarity.

It had been little more than voyeurism to ask about his family, regardless of questions I still had about what I’d read vs. what I’d been told — an attempt to reverse-engineer my own “big drama show.” And wondering whether he “liked” fighting was just a stupid question. None of that would matter in September. Neither would the amateur record, who avoided whom, whether this version of GGG could beat that version of Canelo, the money or the Hall of Fame. As Sanchez said, his fighters don’t know how far they’ll be running when they get up. The past and the future don’t exist.

Golovkin became any person who wants to feel satisfied when he clocks out, like anyone with ambition – albeit at an extraordinary level – who fears boredom more than a broken nose. It now made perfect sense how “GGG” could coexist with “Gennady Golovkin,” the quiet, private “hockey dad,” as Loeffler had described him.

“Sometimes (it) interests me, beating (an opponent),” Golovkin had said earlier, describing no one in particular. “He’s like tall guy, he’s coming … he says, ‘I know boxing.’ ‘OK, show me your boxing.’ Then you (fight) him and you show him he’s nothing. It’s more interest. It’s more … more like …”

Sanchez smiled knowingly and offered a word: “Challenge.”

“Challenge!” Golovkin said. “Yeah, right. Who’s better, you know?”

Canelo has said the same thing: He wants to fight the best. These two boxers are separated by many things, but there’s no reason to doubt that they share this simple desire any less than the ring they will share on September 16.

Golovkin wants to win and he wants to leave no doubt. His ability to do both has shaken the sport of boxing.

With him, that’s all you need to know.

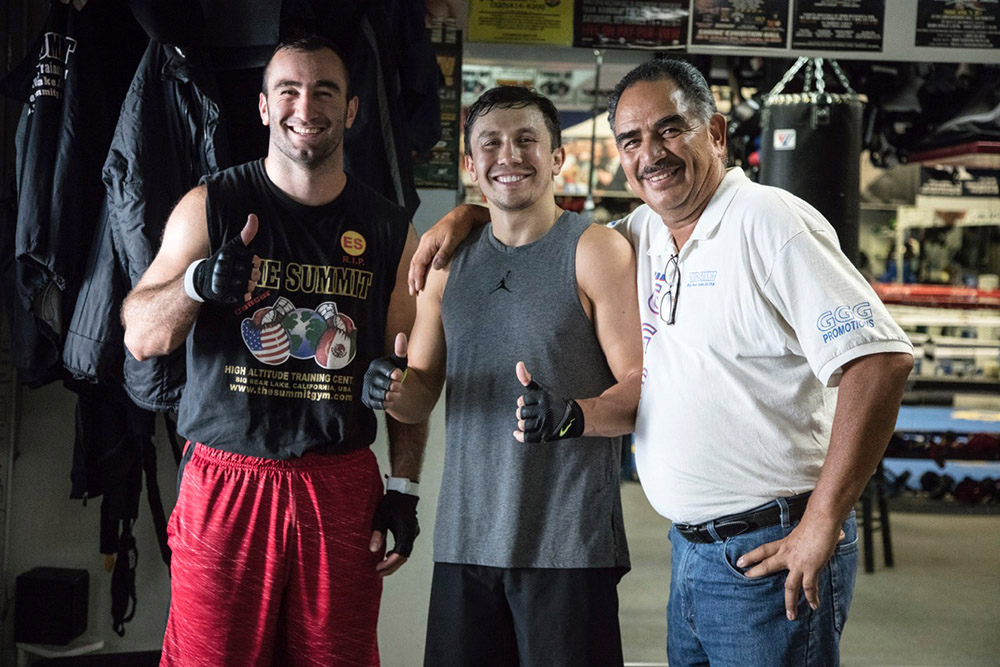

Photos by Ian Hughes (ianhughes.com)

Golovkin stands between cruiserweight gymmate Murat Gassiev and trainer Abel Sanchez at The Summit Gym in Big Bear Lake, California.

MORE CANELO-GGG FEATURES FROM THE RING:

Canelo Alvarez: The different one

Separate Paths: Do fighters with extensive amateur backgrounds (like Gennady Golovkin) have an advantage over those who don’t (like Canelo Alvarez)?

Ranking THE RING’s 31 middleweight champions

This article first appeared in the November 2017 of THE RING Magazine. THE RING, boxing’s foremost publication since 1922, contains in-depth features and commentary from some of the sport’s top writers.