Leigh Montville on Muhammad Ali and more Literary Notes

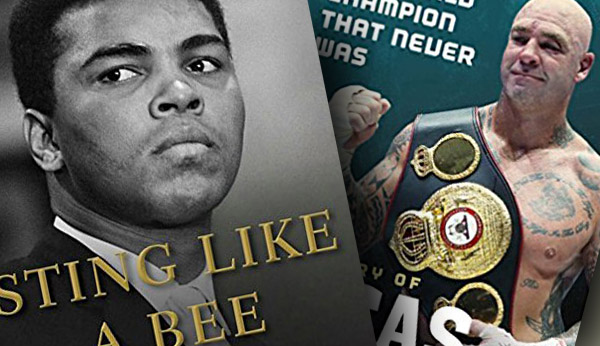

The written history of Muhammad Ali is an ongoing construction. “Sting Like a Bee” by Leigh Montville (Doubleday) is the latest building block in that process.

The written history of Muhammad Ali is an ongoing construction. “Sting Like a Bee” by Leigh Montville (Doubleday) is the latest building block in that process.

“Sting Like a Bee” focuses on the five years from February 17, 1966, when Ali was reclassified 1-A (eligible for military service) by his draft board in Louisville, through June 28, 1971, when the United States Supreme Court unanimously reversed his conviction for refusing induction into the United States Army.

These years included the pre-exile period when Ali was at the peak of his powers as a fighter and fought seven times in less than 12 months through his March 8, 1971, loss to Joe Frazier.

“For a stretch of time,” Montville writes, “1966 through 1971, the most turbulent divided stretch of the nation’s history outside of the Civil War, Muhammad Ali was discussed as much as anyone on the planet.”

That might seem like an outlandish statement. But those who lived through the era can attest to its truth.

Montville paints a portrait of Ali as a gifted, charismatic, talented, determined, sometimes confused young man; often courageous, occasionally fearful, intellectually limited in some ways, insightful in others.

“Pretty much illiterate,” Montville recounts, “he was supremely good-looking and supremely verbal at a time when television invaded everywhere and these qualities became more important. He was part boob, part rube, part precocious genius, somewhat honorable, and could be really funny. He stumbled into his situation, said he didn’t want to go to war because of his religion, put one foot in front of the other, and came out the other end a hero.”

Readers of Montville’s earlier work, such as his biographies of Ted Williams and Babe Ruth, are familiar with his writing style. There are few flourishes. That said, “Sting Like A Bee” has several particularly well-crafted passages, such as the one in which Montville describes Ernie Terrell on the eve of the fight in which Ali savaged him to shouts of “What’s my name!”

“Ali,” Montville writes, “made it sound like he was the first black man who ever lived, the first to fight through injustice. Uncle Tom? Terrell said he would compare hard roads to the Astrodome with this guy any day of the publicity week. He grew up in Inverness, Mississippi, one of ten children. His parents were sharecroppers. His father got a factory job in Chicago when Terrell was in his teens, so everyone headed to the cold north. He was a professional boxer two years before he graduated from Farragut High School. There were no press conferences when the first contract was signed. He never had the carefully planned list of opponents. His style was bang and hold, bang and hold, hit with the left and grind around the ring. He was a defensive fighter, a neutralizer. He had no dazzling speed, no shuffle. He was a survivor. His record was an honest 39-4, and he hadn’t been beaten in five years.”

Montville also gives readers an intriguing portrait of Hayden Covington, the larger-than-life attorney who oversaw much of the early draft-related legal work on Ali’s behalf (and later resigned over unpaid legal fees).

Similarly, Lawrence Grauman, the hearing examiner whose recommendation to the Kentucky Appeals Board that Ali be granted conscientious objector status was ignored, is well portrayed.

And thank you to Montville for debunking the oft-repeated notion that it was Ali who originated the phrase “No Viet Cong ever called me nigger.” The credit for that properly goes to Stokely Carmichael.

Montville has conducted serious research into the legal maneuvering and legal issues surrounding Muhammad Ali and the draft, and brought the source material together in a way that makes it more easily accessed and more fully understood. That’s a valuable service.

* * *

On March 5, 2016, unbeaten Australian heavyweight Lucas Browne journeyed to Grozny (the capital of the Chechen Republic) to fight Ruslan Chagaev. Chagaev was the WBA “regular” world heavyweight champion and a favorite of Chechen strongman President Ramzan Kadyrov, who attended the fight. Trailing badly on the judges’ scorecards, Browne knocked Chagaev out in the 10th round. “Lucas Browne: The World Champion That Never Was” by Graham Clark (Hardie Grant Books) is the story of that fight.

On March 5, 2016, unbeaten Australian heavyweight Lucas Browne journeyed to Grozny (the capital of the Chechen Republic) to fight Ruslan Chagaev. Chagaev was the WBA “regular” world heavyweight champion and a favorite of Chechen strongman President Ramzan Kadyrov, who attended the fight. Trailing badly on the judges’ scorecards, Browne knocked Chagaev out in the 10th round. “Lucas Browne: The World Champion That Never Was” by Graham Clark (Hardie Grant Books) is the story of that fight.

Let’s start with some caveats. Clark was a member of Browne’s team in Grozny, so his objectivity might be questioned. Also, Chagaev-Browne wasn’t a real world championship fight. But sanctioning-body belts, no matter how bogus they might be, are important to fighters.

Clark has an easy-to-read writing style. He describes Grozny as a beehive swarming with Chechen rebels, a spawning ground for Islamic extremists and a safe harbor for the Russian mob.

The climactic fight is well told. Chagaev dominated in the early going. Browne was badly cut, lost a tooth, and endured a stream of damaging body blows.

Round 6, when Chagaev dropped Browne and had him in trouble, was 3 minutes 15 seconds long. Round 7, when Browne turned the tide and staggered Chagaev, was 44 seconds short.

The battle ended in Round 10, when referee Stanley Christodoulou wrapped his arms around a defenseless Chagaev to protect him from further harm. At that point, there was significant concern for Browne’s safety. Rather than celebrate in the ring, Team Browne retreated to the dressing room as quickly as possible.

Sadly, Browne never got his championship belt. After the fight, he was told that it would be sent to him within two weeks. But a post-fight urinalysis by VADA revealed traces of clenbuterol in his system.

Clenbuterol, a banned drug, is used primarily to help athletes lose weight. That made no sense in Browne’s situation, since a 250-pound heavyweight has no need to make weight. Also, all VADA testing of Browne prior to the fight was negative insofar as illegal PEDs were concerned. That lent credence to the theory that Browne was a “clean” athlete and that either he had eaten inadvertantly-contaminated meat or his food had been deliberately laced with clenbuterol.

However, the rules of the game are clear. Athletes are responsible for what goes into their system. Browne was stripped of his title and suspended by the WBA for six months.

“Now,” Clark writes, “it was almost as if the fight had never happened. The achievement had been wiped from the records, the glory had been tarnished, and the story had been retold with the hero cast as the villain.”

Then an even more troubling eventuality occurred. In November 2016, a random test sample taken from Browne by VADA pursuant to the WBC Clean Boxing Progarm tested positive for ostarine (a banned drug that produces effects similar to anabolic steroids).

That leaves Clark to acknowledge, “As with the previous positive result, Browne was unable to explain the finding. This time, sabotage or eating contaminated foods could be immediately dismissed. All notions of a wronged fighter seeking redemption had been blown away. The sporting public hardens its heart very quickly to a man who fumbles his second chance.”

Thomas Hauser can be reached by email at [email protected]. His most recent book – “A Hard World: An Inside Look at Another Year in Boxing” – was published by the University of Arkansas Press. In 2004, the Boxing Writers Association of America honored Hauser with the Nat Fleischer Award for career excellence in boxing journalism.