Muhammad Ali: Truly one of ‘The Greatest’

Editor’s note: This feature originally appeared in the September 2016 issue of THE RING Magazine.

Sometimes it seemed as if we forgot Muhammad Ali could fight. Not just for the causes of racial and social justice, religious freedom and peace and understanding in the world but inside a boxing ring.

Although it was boxing that gave Ali the platform he used to become the most famous athlete in history and one of the most influential people of his time, lost in the Ali shuffle was the fact the man could box.

When Ali passed away on June 3 due to septic shock after a prolonged battle with Parkinson’s disease, the tributes were immediate and unending. ESPN’s Sports Center gave nearly all of several days of broadcasts to his legacy. News channels like CNN did lengthy segments on his life. Social media was atwitter in a way Ali would have loved, with tributes from athletes, political figures and the common man.

All were well-deserved and hard-earned but most focused not on the way he took out Cleveland Williams in stunning fashion but rather on his fights against the United States government after he refused induction into the military on the grounds of being a conscientious objector, thus beginning a 3½- year exile from boxing that ended only after his conviction on draft-evasion charges was overturned unanimously by the Supreme Court.

Much was said and written about his high-profile conversion to Islam and his name change from Cassius Clay to Muhammad Ali, which was announced immediately after first winning the heavyweight title from Sonny Liston in 1964. Twice in a matter of days he had, for the first but not the last time, “shocked the world!” He did that first with his boxing skills, it should be noted.

The great gifts of speed, nimbleness, deadly accurate punching and a stinging jab that flicked out with the same ominous warnings of worse to come as a rattlesnake’s tongue, were the first signs of greatness in Muhammad Ali. They came before his oratory, his humor, his courage and his long-held insistence on racial and religious freedom and social justice for people long downtrodden and ill-treated. To remember that he was a boxer first is not to trivialize all he stood for. It is only to remind us what gave him the worldwide stage he strode upon.

It was Ali the Boxer who allowed Ali the Man to flourish. Had he not possessed arguably the fastest hands and feet heavyweight boxing has ever seen, he might well have still taken the social positions he did but would they have carried the same weight? Would a glib porter or fast-talking salesman who converted to the Nation of Islam have had the same impact on the world as the heavyweight champion? Obviously not. So to shortchange recollections of that side of Ali is ill-advised, for it was the foundation for all he accomplished.

Heavyweight boxing in the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, the time when Ali reigned supreme among heavyweights whether he was wearing a champion’s belt or not, was the division’s greatest and most competitive era. To be heavyweight champion in those days carried a gravitas it no longer does because boxing was not only a mainstream endeavor but one of the most significant sports in the country.

It was not a niche sport, as it has become today for many. A boxing match featuring Muhammad Ali was front-page news. It was an international event watched for free on television on a Saturday afternoon or as a closed-circuit broadcast in movie theatres around the world.

It was a time when the depth of world-class heavyweights was never greater and so the climb to the top was steeper. Ali was two different fighters during this time, separated by nearly four years of government-imposed exile. In both cases he was a genius of fistic jazz. He was not Glenn Miller, keeping the beat. He was Miles Davis altering it in ways unfathomable to the rest of us.

Technically, he did so many things wrong it made your head spin. He didn’t so much slip punches as pull straight back from them, one of the most fundamentally unsound moves in boxing. He made it work.

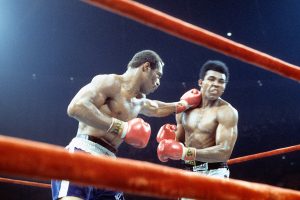

Muhammad Ali (left) battles Joe Frazier in fight two. Photo by THE RING

He fought often with his hands slung low, in his pockets if boxing trunks had pockets. That dangerously exposed his chin and made boxing’s elders warn that he would be a resident of the sport’s dark room once a skilled opponent nailed him. They seldom did in his first iteration and in the second he took the blows he used to elude and fought with steely determination.

Joe Frazier put him down … once. Henry Cooper did it … once. But seldom did anyone else come close to hitting him in those early years because, like Miles Davis, Muhammad Ali the Boxer made wrong right.

“Every 20, 25 years an athlete comes along who is a complete game-changer in a physical sense,” said Showtime analyst and boxing historian Steve Farhood. “Ali was that for heavyweight boxing.

“At 6-3 and 215 pounds he was big for his time but until Ali the bigger heavyweights were all lumbering, slow-footed guys. They couldn’t move. He was the fastest heavyweight in history. It was those superior physical skills that allowed him to get away with all his technical deficiencies. Despite them, he was so fast he barely got hit in his first run.”

He dominated the division not only in that first incarnation as the fastest heavyweight boxing has ever seen but also in the second, when he returned to the ring on Oct. 26, 1970, after a 43-month layoff when his boxing license was suspended in every state in the Union and his passport revoked so he could not ply his trade overseas. He came back not to face some tune-up hump but rather Jerry Quarry, a title contender who had lost bids for the heavyweight championship to Jimmy Ellis by majority decision and stoppage to Joe Frazier. Quarry was as relentless as a termite and tougher to navigate than 10 miles of detour. Ali stopped Quarry on cuts in three rounds.

He then became the only man to knock out Oscar Bonavena, the WBA’s No. 1 contender, dropping him three times in the 15th round to put himself in position to challenge his old friend and lifelong nemesis, Frazier, for the first time. That fight was considered the match of the century because it came heavy with social issues, poor Frazier unfairly labeled as the representative of the old ways and the Silent Majority that favored the Vietnam War and opposed Ali. But it was the skill and the will of the two fighters on March 8, 1971, that made it one of boxing’s most memorable moments.

It was in that fight, which Frazier won by unanimous decision and during which he dropped Ali with a massive left hook in the final round, that it became clear Ali was not the same fighter he’d been before his exile. While still quick by heavyweight standards, he was not so fast anymore that he could not be touched.

The Ali Shuffle was still there but as time wore on the great fistic musician would sometimes hit an off-key note and when that happens in boxing the audience isn’t the only one that cringes. So does the fighter and the pain is not only in his ear. It’s often in his brain or his ribcage.

Ali the Boxer had to reinvent himself and he did that so effectively he became even more popular and twice more a heavyweight champion. But now it was as much his ability and willingness to take punishment while still being able to dish it out that set him apart.

“His speed wasn’t what it had been but we found he had other things,” veteran trainer and ESPN analyst Teddy Atlas explained. “He had intelligence. He had grit. And he had that chin. He always had those things but we never knew that the first time because no one tested them. When they did, he passed the tests and remained great. Different but still a great fighter.”

Ali (right) at war with Ken Norton in their second fight. Photo by THE RING

Ali’s jaw was broken in the first round of a split-decision loss to Ken Norton two years after the first Frazier fight but he went the distance despite the pain and defeated him in an immediate rematch and again three years later. Some will debate that Norton won two of those fights but the larger fact was it was now a slower, more resolute Ali who was doing the boxing and still finding ways to win.

A perfect example of the difference was the Rumble in the Jungle, when he first out-thought and then out-fought the relentless and seemingly unbeatable George Foreman. He had done the same to Liston, who was as feared in his time as Foreman was in 1974, but that time it was with blinding foot speed Liston cold not catch up with. This time Ali did it not with speed and agility, as he most surely would have done 10 years earlier, but rather with quickness of mind and hand, the resilience of his spirit and the stoutness of his chin.

That Ali took every blow Foreman could muster, mostly by lying on the ropes and absorbing them like a sponge in the sweltering heat of the pre-dawn hours in Zaire. He wore young Foreman down not with the movement that was now mostly gone but with his will until a 25-year-old champion seen as invincible became an empty vessel who could barely raise his arms.

Then Ali the vicious closer went to work like a symphony conductor, taking Foreman apart with stinging jabs and lead right hands amateurs should not be hit by until he finally sent him to the floor with a brilliant combination.

Sweat flew into the air as punches snapped Foreman’s head back. When he began to fall, he was vulnerable to one last locked-and-loaded right to his face but Ali chose not to throw it. It was a note he did not need to play and so he held back. The song was over. A tune no one had expected had been heard and it was beautiful music but the kind only a virtuoso of the ring could deliver.

That was the real genius of Muhammad Ali – what he did in the ring. His other accomplishments were more significant and more lasting, of course. They affected the world and the larger society in ways no boxing victory could. But it was his transcendent boxing skill that made all the rest possible. They should be fully remembered too.

He called himself “the greatest of all times” and that can always be debated. Advocates for Sugar Ray Robinson are many. A case can be made for Henry Armstrong, who held three titles in three legitimate weight classes simultaneously and wasn’t called “Homicide Hank” for nothing. If you come from a different time you may argue for Sugar Ray Leonard or Joe Louis. But one thing is clear: There has never been a heavyweight who could do the things the first Muhammad Ali did and not many who could have accomplished what the second did either.

Was he, purely as a fighter, the GOAT? Was he even the best heavyweight ever? Debate that if you like but Joe Louis is the only one truly in the heavyweight conversation with Ali and whatever list of boxers Ali is on doesn’t have many names on it. In the end, that is what allowed him to become all he became to so many. Boxing opened the door. Ali did the rest.

Struggling to locate a copy of THE RING Magazine? Try here or…

SUBSCRIBE

You can subscribe to the print and digital editions of THE RING Magazine by clicking the banner or here. You can also order the current issue, which is on newsstands, or back issues from our subscribe page. On the cover this month: Vasyl “Hi-Tech” Lomachenko.