Canelo-Chavez Jr.: The Fight for Mexico

Note: This feature appears in the current issue of THE RING magazine.

They share a language, culture and country. It was inevitable, perhaps, that Canelo Alvarez and Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. also would share a ring one day.

How they got there, however, is a complicated path, unpredictable at almost every turn. Along the way, there is Mexican history, national pride, personal legacy, family and finances. For nearly a decade, the fight was imagined, then forgotten and finally resurrected for May 6.

Yet despite all that has been said and seen, the fight itself remains as hard to judge as just about everything that has preceded it. Maybe that’s appropriate. Maybe not. Maybe it’s not much of a contest at all. Maybe it’s more of an event than a real fight. Maybe, maybe, maybe.

All of those maybes are maybe reasons to watch a couple of fighters who are well known on both sides of the border, so well known, in fact, that we call them by their first names as if they were kids in the neighborhood. It’s Canelo. It’s Julio Jr.

The kids have grown up and now they’re finally going to fight. It will be played out on an international stage at Las Vegas’ T-Mobile Arena in a pay-per-view bout. Yet the fight has divided a country as if it were a small community split by rival Little League teams. Late Massachusetts congressman Tip O’Neill, a former Speaker of The House, famously said, “All politics is local.” He could have been talking about boxing. It’s at its very best when it’s local. That’s when the stakes are personal, almost tribal.

Never has a fight been more personal than the one about to unfold between Canelo and Julio Jr.

“The rivalry has always been there between Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. and me, but obviously during the tour there were a lot of things said behind the cameras that made it even more intense,” Canelo said at the end of four-city press tour in mid-February.

In some ways, the seeds of the rivalry were there long before either was even born. Start with Mexican history, the nation’s singular pride in boxing and a family legacy.

Julio Jr.’s dad is known as El Gran Campeon Mexicano, Mexico’s Grand Champion. The son has his dad’s name, an iconic symbol that has been both a benefit and burden.

The benefit, an inherited entitlement, came in the form of a Top Rank contract despite only two amateur bouts against another one of Mexico’s boxing sons, Jorge Paez Jr. Then there was favorable matchmaking, all in return for a son with a legendary name that still has a pied piper’s ability to draw a crowd.

On the flip side, there was that burden. For Julio Jr., an apprentice fighting as a pro, it was a crushing inability to even approach the kind of fighter his dad was. Then again, who could?

On the flip side, there was that burden. For Julio Jr., an apprentice fighting as a pro, it was a crushing inability to even approach the kind of fighter his dad was. Then again, who could?

But stories emerged about Julio Jr.’s lax training. Before a one-sided loss to then-middleweight champion Sergio Martinez, Freddie Roach, then Chavez’s trainer, said that Julio Jr. trained when he felt like it, often in the wee hours after midnight at a condo in Las Vegas. The story led to jokes about Julio Jr. doing his roadwork with a few laps around the condo’s couch.

Then there were subsequent positive tests for a banned diuretic and marijuana. He struggled to make weight and when he didn’t, rules were re-written in a way that allowed him to fight as if a few extra pounds were also part of the entitlement.

All of that and more angered Mexican fans loyal to the dad and all that the name represents. First, there were boos. Then, there was contempt. The son was more Peter Pan than El Gran Campeon.

But the bout against Canelo represents a second chance, an opportunity for the son to restore his image and the family name. The best way to do that is with a victory that would rank as a significant upset. When the fight was announced on January 13, Canelo was a 4-1 favorite.

“Winning takes away a lot of the criticism,” Chavez said in Los Angeles, the final stop in the four-city tour. “But I also feel I’ve been over-criticized. I get the criticism just because I am Senior’s son. For all the good I do, I feel it counts for half. And any of the bad is doubled because of the limelight that’s on me.”

It was that criticism – fierce and dismissive after losses to Martinez in 2012 and later to Andrzej Fonfara 2015 – that seemed to finally eliminate any chance of Julio Jr. against Canelo. Increasingly, it looked as if Canelo had emerged as Mexico’s heir-apparent to Julio Sr.

Canelo is a good story with looks that make Mexicans think about another part of their history, Los Patricios, the Saint Patrick’s Battalion of Irish immigrants who deserted during the Mexican-American War, 1846 through 1848. The Irish complained about discrimination from American Army officers. Angry, they jumped to the other side and fought for Mexico in a losing cause. Fifty were executed. Mexican soldiers called them Los Colorados for their red hair and sunburned faces.

Other than that familiar red head, there’s nothing that links Canelo (“Cinnamon”) to Los Patricios. Still, many of his fans see it and think about another chapter in Mexican history, older than Julio Cesar Chavez Sr., symbolic of Mexico’s deep pride in its warrior past.

But Canelo’s quest to be the next Julio Sr. has encountered some its own trouble, especially lately. He enters his bout with the legend’s son amid pointed questions. Many have been building over the last few years. And some are not unlike those asked about Julio Jr. Critics say Golden Boy, his promoter, has matched him against opponents who were smaller, or overmatched, or both the past few years.

The chorus grew loud and nasty in the wake of a 2013 loss to Floyd Mayweather Jr. The majority decision was one-sided in every way, despite a baffling draw on one scorecard.

“Embarrassing,” said Rafael Mendoza, Canelo’s first and former manager, who has been critical of Canelo’s corner, Chepo and Eddy Reynoso.

Then there are fans further exasperated by the fact that Canelo has yet to fight Gennady Golovkin.

GGG was at ringside for Canelo’s scary knockout of Amir Khan last May at T-Mobile. Canelo invited him into the ring, saying he would fight him then and there. He also said, “Mexicans don’t f— around.”

About a week later, Canelo vacated his 160-pound title without any immediate plans from Golden Boy or the Reynosos for a GGG showdown in 2016. The outcry in Mexico was deafening.

There was something else, too. There was a renewed hunt for the fighter who could succeed Julio Sr. and fulfill the spirit represented by Los Patricios.

There was something else, too. There was a renewed hunt for the fighter who could succeed Julio Sr. and fulfill the spirit represented by Los Patricios.

“I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: Julio Cesar Chavez Sr. is one of the best, if not the best fighter in history,” Canelo said during the L.A. leg of the press tour, which also included Mexico City, New York and Houston. “I grew up watching him and learned a lot from him, but that won’t have any influence when I fight his son.

“You haven’t seen the best of me. Every fight, I keep getting better. And I hope this one brings out the best in me.”

Most of the pressure appears to be on the younger Canelo, 26. The betting odds and talk suggest that the Chavez fight is simply a stepping stone toward a proposed showdown with GGG in September. The idea is that Chavez has nothing to lose. But Ricardo Jimenez, a former sportswriter at La Opinion and a longtime publicist, disagrees.

“No,” said Jimenez, who worked with Julio Jr. when both were with Top Rank. “I think that Chavez Jr.’s career is on the line and he needs a great showing to keep going. How he makes the weight will be important and how he looks in the fight will be important. I think he has a lot at stake in this fight and has to deliver a great performance for himself and for his fans.”

After the press tour, there was more talk about the fight from Julio Jr. than Canelo. It’s almost as if Julio Jr. is campaigning while training, selling the bout as a uniquely Mexican battle for the right to succeed his dad.

“The Mexican people are very excited and very indecisive,” Chavez Jr. said during the Los Angeles stop. “This same thing happened with Marco Antonio Barrera, Erik Morales, Juan Manuel Marquez when they were in their prime. Who’s the favorite?

“It feels like they’re just waiting to see who wins to decide who they’ll follow.”

A divide between the Canelo and the Julio Jr. camps is there. But there are no numbers. There have been no polls, not that anybody believes in them anymore.

“I was told that in Mexico City the crowd was divided,” Jimenez said. “In Houston it was for Canelo and in Los Angeles it was a Chavez Jr. crowd. Both guys have a lot of critics also. I think at the end of the day both guys have big fanbases and with the fans is a 50-50 proposition.”

In a move that serves as a further Mexican accent on a Las Vegas fight, Julio Jr. hired Nacho Beristain. In Mexico, Beristain is to training what Julio Sr. is to fighting. He’s the best ever, El Gran Entrenador. More important, he’s a no-nonsense disciplinarian. If Julio Jr. sticks to Beristain’s regimen, some say he has a real chance.

“Unlike a lot of people, I believe he has a lot skill,” Top Rank’s Bob Arum said of Julio Jr., who signed with Al Haymon in November 2014. “If Julio Jr. is serious, trains hard and listens to Beristain, then I give him a real chance. It’s all in his hands.”

It’s also in his diet. The contract mandates a catchweight, 164.5 pounds. For Canelo, the weight is a move up from 154 pounds, where he has been successful. It’s also seen as an important step in getting him comfortable in a heavier division in preparation for GGG, the most feared middleweight of his generation.

For Julio Jr., it’s a move down the scale. That could be a challenge. His struggles are no secret. His last fight was at super middleweight, 168 pounds, in a victory over German Dominik Britsch in December. In July 2015, he missed weight against Marco Reyes but was allowed to fight and win at 170 pounds, instead of 168. In April 2015, he quit after nine rounds in a 172-pound catchweight bout with Fonfara.

Julio Jr. argues that Canelo has never fought anybody his size. Fact is, Julio Jr.’s power nearly knocked out Sergio Martinez in a 12th round as wild as any at Las Vegas’ Thomas & Mack five years ago. Against Martinez, his heavy hands were almost enough to offset his lack of conditioning.

Still, there are questions about whether a battle to make weight will weaken Julio Jr. for a fight that figures to include Canelo’s punishing combos to the body.

“I think most people believe that Canelo will win, because he has been a more disciplined boxer and there are many questions about Julio Jr.,” Jimenez said. “But Junior has his followers and a lot people think he can win the fight, because he’s a bigger man and harder puncher.”

It’s that intense debate, perhaps, that will sell a fight that in hindsight looks preordained. Over time, it has been created by events, coincidence and cultural events – all much bigger than either Canelo or Julio Jr.

“I was surprised how big the fight is to so many fans,” Jimenez said. “I was at the L.A. press conference and the press and fans turnout was huge. I think the timing of the fight is perfect for both guys.

“It’s hard to say it’s a big fight as a boxing match, but it is a big event. Both Canelo and Chavez have huge followings. I don’t think two Mexican fighters in a pay-per-view main event have ever drawn this kind of attention. Their popularity and their personal grudge make it a big fight.”

Big enough maybe to even make some history.

Struggling to locate a copy of THE RING Magazine? Try here or…

SUBSCRIBE

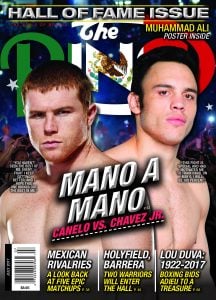

You can subscribe to the print and digital editions of THE RING Magazine by clicking the banner or here. You can also order the current issue, which is on newsstands, or back issues from our subscribe page. On the cover this month: Canelo vs. Chavez Jr. – Mano A Mano.