Haye, Bellew and the ‘Perfect Prizefight’

To box professionally is to lie for a living. To yourself, to others, to the public. In time, you might even get good at it. You might, for instance, convince yourself and your audience that you’ve had the best training camp of your career when knowing the truth is quite the opposite. You might preach a desire to fight the best and most dangerous fighters in the world when knowing your preferred path is a safer one: remain undefeated, avoid risks, make money. You might express hatred for an opponent, a man or woman you hardly know, purely because you understand hate generates interest and interest generates money. They’re all lies. All said for self-preservation or strategy. All part of a boxer’s vocabulary and DNA. All acceptable within the parameters of the hurt business.

David Haye and Tony Bellew are no different. Both have said things that didn’t come true. Such shortcomings make them human, make them risk-takers, make them boxers, and a habit of speaking out of turn makes them eminently watchable. Their next project, a joint venture, a U.K. pay-per-view event, will take place on March 4, 2017 in London, England. Both will again exaggerate to sell it. Both will expect a significant return on their investment.

Hence.

Haye: “I could go clubbing every single night from now to the fight, get smashed every night and still knock you out. I could turn up drunk off my head. You’re getting knocked out. Destroyed. I’ll be standing over your limp body in the ring.”

And: “Even if you do hit me, nothing is going to happen, you powder-puff-punching chump. I’ll end the fight when I want to. If I want to punish you for three or four rounds, I’ll do that. If I want to take you out in 30 seconds, I’ll do that.”

Bellew: “He could have fought for the heavyweight championship of the world but he chose the money because he’s skint. You’re struggling and you don’t want a real fight.”

And: “I know you’re as fragile as they come.”

The public’s reaction to the fight, announced last Friday, has been divided. Some have gone gaga for the drama of it all, whereas others seem skeptical because the sales pitch involves two men for whom subtlety is a foreign word. It’s true, of course, that Haye and Bellew tend to shoot for the lowest common denominator: hate. They are, in many ways, masters of this unsightly art. But the accusation, I guess, is that when ill will becomes such a frequently used sales tactic people begin to question its authenticity. Can you really dislike that many people? What’s more, a desperate need for animosity in the lead up to a fight often masks its shallowness or lack of appeal; too many manufactured grudge matches can act as a damning indictment of the state of a fighter’s resume.

Still, on the evidence of yesterday’s London press conference, the brand of hate Haye and Bellew are pushing seems legitimate enough. It was surely too personal, too bitter and too damn nasty for it to be the work of second-rate actors.

Photo: Lawrence Lustig

More insightful, I thought, was the outburst Haye directed the way of the show’s promoter, Eddie Hearn, a man denounced for hogging the limelight, making everything about him and for not being a patch on his father, Barry. Taken aback, Hearn’s reaction was to smile the awkward smile of a promoter and counter by saying Haye was bitter because he, the fighter, wasn’t independently promoting the event (thus maintaining complete control and banking all it generates). It was odd really, this infighting, because those at the top table share much in common and are cultivators and beneficiaries of the very same thing: a social media and pay-per-view-driven golden age of bullsh_t and banter and Nando’s and LadBible which grooms so-called ‘casuals’, financially rewards egos and blowhards and makes boxing again seem like an appealing night out. Gone are leisure centers and the stench of chlorine. The British scene has never been better.

Hearn: “It’s an event that has already captivated the minds of sports fan around the world. We have a huge event on our hands to kickstart 2017.”

Sky Sports’ Adam Smith: “We’re massively behind this event.

“In my opinion they are the two biggest personalities in British boxing.”

The event.

The personalities.

HBO’s Larry Merchant once told me he prefers the term prizefighting to boxing. Boxing, he said, gives a false impression. It’s a word boxers conveniently hide behind when putting on the kind of performances that drive fans away; hit and not get hit, the sweet science, boxing. Prizefighting, on the other hand, speaks to the greater need to entertain, the need to deliver, the need to satisfy, the need to properly earn a wage. Fight for your prize. It also makes a clear distinction between the amateur and professional codes. Amateurs fight for competition. Professionals fight for money. Some care more about titles and legacy than others, some may even lie about their reasons for doing it, but, when all is said and done, prizefighters fight for one reason: they want to be able to call punching people in the face their livelihood.

No doubt boxers are brave and deserving of respect, but it’s important to view their bravery in context. Boxers are brave because they are paid to be brave just as they decide to fight because they are paid to fight. What we witness on fight night, therefore, is no selfless act, nor is it necessarily “for the fans” as many like to proclaim. It is, in actual fact, a well-thought-out business decision. They have elected to fight because, to them, fighting is the most logical way of making money; lots of it, too, especially if they scale the heights. Sure, there’s a risk whenever a boxer sets foot inside the ring, but it’s one weighed up against its reward. Some people, for the sake of further context, quietly fight fires and save lives for pittance.

In the realm of boxing – that pure, idealistic thing which doesn’t really exist – Haye vs. Bellew is as cynical a pay-per-view match-up as there is in Britain right now. Deconstructed, it’s a non-title fight between a 36-year-old heavyweight who hasn’t fought a recognizable opponent or seen a third round since 2012 and a cruiserweight titlist who weighed 175lbs three years ago. On that basis, it’s strange, confusing, pointless. Pitch and embrace it as a prizefight or event, however, and it makes complete sense. It makes more financial sense, in fact, than any other option either man could deem an alternative.

Let’s go, champ! Let’s go, champ! Let’s go, champ!

All well and good, Shannon, but no amount of shouting will put our epic grudge match on pay-per-view. Without that, you won’t get paid, I won’t get paid, nobody will get paid. Let’s call the whole thing off, champ.

Tony Bellew, for his part, will have also analyzed the cruiserweight landscape and decided there is no better time to leave it behind. Big fights? Nada. Big challenges? Absolutely. There’s a discernible, dangerous difference. Denis Lebedev, Oleksandr Usyk, Murat Gassiev and Mairis Briedis are tough-to-pronounce names against whom little fun will be had and little money will be made.

Consequently, nine years on from Haye’s last cruiserweight fight (a Brit on Brit thumping of Enzo Maccarinelli), Haye vs. Bellew at heavyweight is the prizefight that today makes sense. The right prizefight at the right time; a stop-gap before either Haye (if he wins) hunts down Anthony Joshua, the jewel in the crown of British boxing, or Bellew (if he wins) utilizes an enhanced profile to make treacherous cruiserweight title defenses pay-per-view events. And because we’re accustomed to forking out for tune-ups and catchweight fights masquerading as superfights – the boxing business model circa 2016 – there’s a sense it’s the natural order.

For purists who oppose it, you have Andre Ward vs. Sergey Kovalev. Two world-class fighters who duked it out for a number of titles. Boxer vs. Puncher. It meant something. It was real and true. The way it used to be. The way it’s supposed to be. The fighting equivalent of fine dining.

It also registered just 160,000 pay-per-view buys in the U.S.

Haye vs. Bellew, meanwhile, a McDonald’s Happy Meal of a prizefight by comparison, will do at least four times that amount in the United Kingdom. And that’s if they don’t say another word.

Photo: Lawrence Lustig

I’m calling it a prizefight. Some are using mismatch. Certainly, the argument that a man knocked out by Adonis Stevenson and outpointed by Nathan Cleverly at light-heavyweight has zero chance of defeating a heavy-handed heavyweight like Haye is a valid one. Perhaps even obvious. But Bellew’s momentum and improvement at cruiserweight, his natural weight class, combined with Haye’s age and inactivity adds a layer of intrigue. Bellew has fought 13 times since Haye cracked Dereck Chisora at Upton Park Stadium. Yes, thirteen times. He also, this year, short-circuited Ilunga Makabu at Goodison Park, home of his beloved Everton football club, a performance which not only bagged him a WBC title and upset the bookmakers but was probably the best I’ve witnessed in a British ring in 2016. Better yet, it came with all the priceless trimmings of a big fight night; the test, pressure, the anxiety, the fear, the rush. Things Haye has been without since 2012.

It all amounts to mystery, question marks, enough to make it interesting. We know Haye knows how to fight. He has been doing it since he was ten; launching right hands, knocking men out, being violent. We know Haye at 27 was an excellent cruiserweight. We also know Haye at 30 was a good heavyweight, if undersized and occasionally flattered by soft opposition. But Haye at 36 is an enigma. Wins over Mark ‘The Dominator’ De Mori and Arnold ‘The Cobra’ Gjergjaj – the latter having collapsed and hyperventilated following a jab which missed – were as revealing as a burka, and therefore an evaluation of Haye based on 2016 is much like evaluating Robert De Niro not on his seventies and eighties run but on ‘The Adventures of Rocky & Bullwinkle’ and all that followed.

What we definitely do know is this. When the cameras stop rolling and the time to sell has expired, all that’s left is belief (as is the case with all fights, whether in rings, cages or on playgrounds, whether for money, titles or pride). It will all get real at some point. The panto, the promises, the punches. The ring sieves the bluster to leave only the truth. And if Bellew genuinely believes he can beat Haye, due to knowledge gleaned from a sparring session, Haye’s inactivity, or sheer confidence in himself, he stands a chance. More than a puncher’s chance. If, however, Bellew’s belief that he can move to heavyweight and beat Haye was expressed solely for the purpose of first securing and then flogging a prizefight, Audley Harrison is better positioned than I am to explain how and why a payday won’t eradicate pain.

Six years ago I sat with Haye in his hotel room hours before that Harrison fight – that event, that non-event, that slaughter – and recall asking him to sum up boxing in one word.

He gave me two (or three, pedants).

“Smoke and Mirrors”.

Struggling to locate a copy of RING magazine? Try here or…

SUBSCRIBE

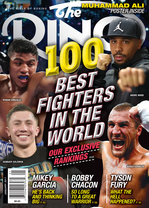

You can subscribe to the print and digital editions of RING magazine by clicking the banner or here. You can also order the current issue, which is on newsstands, or back issues from our subscribe page. On the cover this month: THE RING 100.