The Travelin’ Man goes to Sands Bethlehem Event Center: Part one

Friday, March 4: Less than two weeks after returning home from Atlantic City, this Travelin’ Man will be heading back to a similar part of the country. But instead of flying to Philadelphia and driving to the onetime boxing capital of the eastern US. as I did last time, I will be climbing into my trusty Subaru and making the long journey to the Lehigh Valley, where, in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, I’ll be working a Showtime tripleheader featuring a quartet of middleweights (Tony Harrison vs. Fernando Guerrero and Antoine Douglas against late-sub Avtandil Khurtsidze) and an IBF junior middleweight title eliminator between Julian Williams and Marcello Matano in the main event.

Bethlehem is not an easy place for me to reach, either by plane or car, and experience taught me both options require roughly the same amount of time. When I chose to fly, two options were available: Pittsburgh to Philadelphia to Allentown or Pittsburgh to Philly and then drive more than 90 minutes to Bethlehem. This time, however, I chose to make the seven-hour, 404-mile drive because (1) instead of the airline, I would be in control of when I come and go and, (2) unlike many people, I like long drives, especially when cruise control is available.

I chose to leave shortly before noon because I spent the morning finishing several necessary tasks. It was a typical West Virginia winter day: A stone gray sky, a light dusting of morning snow and a temperature in the 30s. My Magellan GPS – last used during a late-December trip to Houston – took surprisingly little time to “find” me and, thanks to a recently-found car charger, I didn’t have to worry about the device running out of power.

Because the first two hours of the drive were identical to the route I take to Pittsburgh International Airport, my mind had the luxury to ponder other thoughts. Of course, boxing’s glorious past is never far from my mind and I couldn’t help but be reminded that three significant anniversaries were days from occurring: Wilfred Benitez’s shocking upset of Antonio Cervantes on March 6, 1976, the 45th anniversary of the first Joe Frazier-Muhammad Ali fight on March 8 and the 30th anniversary of Showtime’s first boxing telecast.

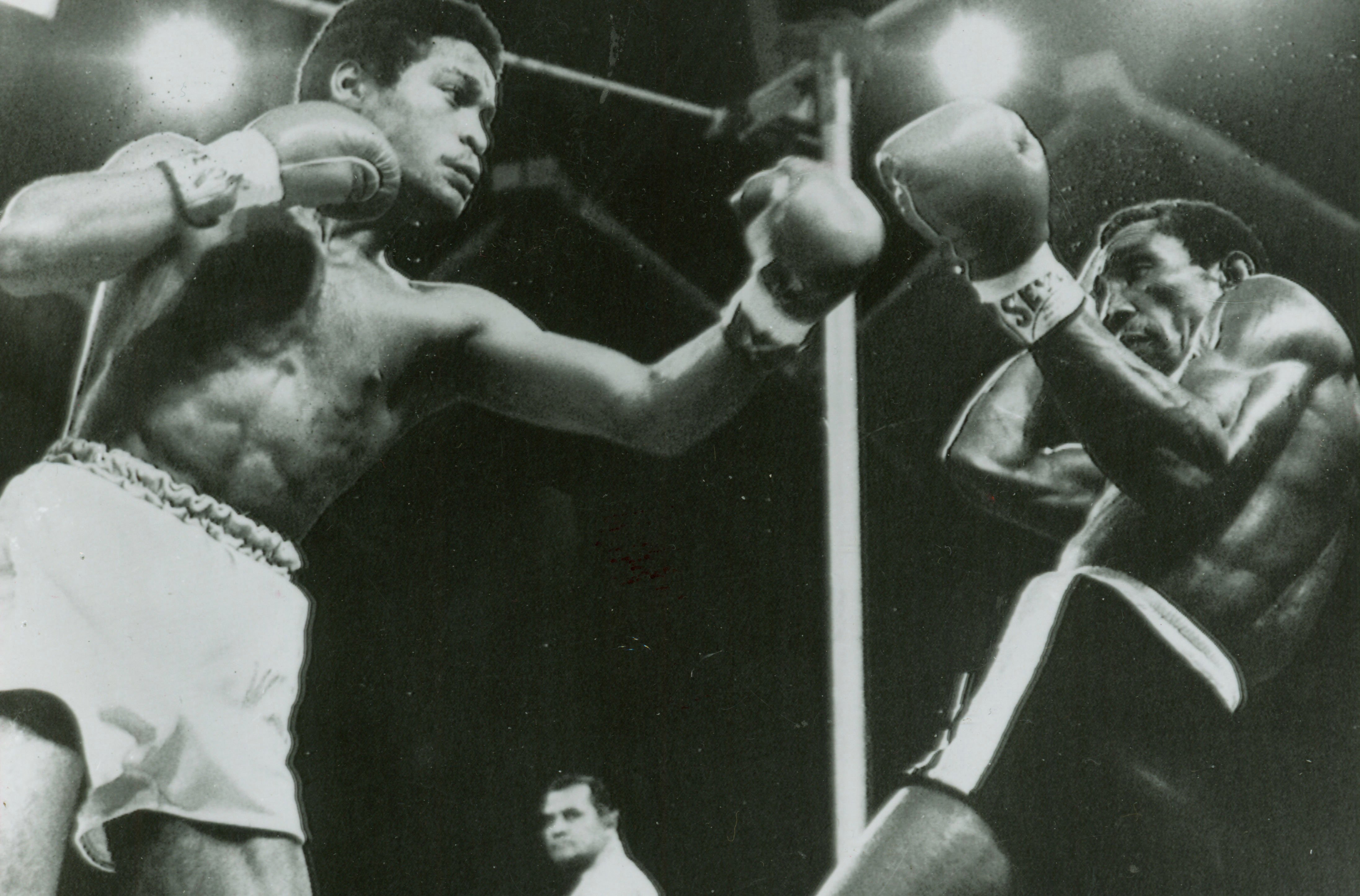

Benitez-Cervantes was one of the most astonishing upsets of the 1970s, not just because Benitez defeated one of the greatest 140-pound champions to ever live but that (1) he was 17 years 180 days old when he achieved it and (2) he did it by out-boxing the classy Cervantes. With the victory, Benitez became the youngest fighter ever to win a version of a world boxing championship and did so with room to spare. Johnny Coulon was 18 years 334 days old when he won the American version of the world bantamweight title from Kid Murphy in January 1908 while Terry Baldock was 18 years 354 days when he won the British version of the bantamweight title by outscoring Archie Bell over 15 rounds in May 1927. For the record, Tony Canzoneri was 18 years 356 days old when he won the world bantamweight championship from Johnny Dundee in October 1927, the closest past equivalent to Benitez-Cervantes.

Cervantes entered the ring as a solid 4-to-1 favorite but even that didn’t reflect the gulf between their resumes. “Kid Pambele” was making the 11th defense of the WBA junior welterweight title he won three-and-a-half years earlier from Alfonso “Peppermint” Frazer in Frazer’s native Panama and, in that time, he established himself as one of boxing’s best pound-for-pound fighters. At 5-foot-9 and armed with a 72-inch reach, Cervantes blended elegant boxing skill with crackling power. Cervantes’ reign featured several highlights. First, he avenged his shutout decision loss to Nicolino Locche in Venezuela (a TKO 9). Second, he crushed Frazer in five rounds in their rematch in Panama. Third, he scored eight knockdowns of Shinichi Kadota in Tokyo before putting him away in the eighth. Fourth, he dropped recently deposed lightweight titlist Esteban DeJesus three times in posting a dominant decision victory and fifth, in his most recent bout, Cervantes put away rugged Australian Hector Thompson thanks to a right uppercut that opened a fight-ending cut in round seven. At the time he met Benitez, a mouth-watering super-fight between Cervantes and lightweight champion Roberto Duran was being discussed.

Given Cervantes’ resume, Benitez, despite entering the ring with a 25-0 (20 knockouts) record, was given little chance of derailing the elegant Colombian’s drive toward Duran. That said, if ever a boxer can be equated with Mozart, in terms of precocious talent, it was Benitez. Even at age 14, when Benitez out-pointed Camille Huard on an amateur boxing telecast aired in 1972 on ABC, the Puerto Rican was uncommonly poised and impossibly skilled for someone so young. Even then, Benitez slipped and countered with the fluidity and muscle memory of someone twice his age. Turning pro the next year, Benitez tore through his early competition, stopping his first five opponents and 12 of his first 13. He impressed the New York City press as he beat Al Hughes (TKO 5), Terry Summerhays (TKO 6) and Lawrence Hafey (UD 8) in consecutive fights between Sept. and Dec. 1974 and, entering the Cervantes fight, Benitez was nearly three months removed from a 10-round points win over the 26-11-4 Chris Fernandez.

While wonderfully talented, Benitez still was attempting a quantum leap upward by facing Cervantes. Not only was he fighting a certified future Hall-of-Famer, Benitez had only fought past the eighth round three times and was now scheduled to box 15. Even though he was blessed with uncommon talent, no one knew if he had the stamina to go the distance against anyone, much less against someone of Cervantes’ caliber.

Cervantes’ management wasn’t concerned that he would be fighting Benitez in the challenger’s hometown of San Juan. After all, Kid Pambele scored a split decision over Josue Marquez there in his first defense and he had notched several title fight victories away from Colombia. Plus, Benitez was just a kid. How much damage could a teenager do against a 86-fight veteran who, at age 30, was still at the top of his game?

From the start, Benitez exuded confidence, so much so that he broke into a mini-shuffle during the first minute of the fight. He had even more reason to feel that way when he was able to draw Cervantes into a scientific jabbing contest, while also preventing the champion from landing his vaunted right. It soon became evident that, despite the wide gaps in age and experience, Benitez belonged in the same ring.

In round two, Benitez landed several clean blows to Cervantes’ face that brought roars from the partisans that braved the rainy conditions to pack Hiram Bithorn Stadium. Cervantes picked up the pace in round three but Benitez proved equal to the task as he slipped the blows, answered with piercing jabs and even pelted him with a right hook from the southpaw stance. After tasting a flush right to the face, the unflinching Benitez waved his glove and asked for more.

Round after round, Benitez passed test after test. He showed he could engage Cervantes in close quarters and knew enough tricks to keep the Colombian honest. Benitez used foot feints to force Cervantes to take a half-step back instead of planting his feet to punch and the youngster possessed enough pop to keep Cervantes from trying to bully him out of the ring. No matter what questions Professor Cervantes asked, the ace student produced the correct response, most often in the form of stabbing jabs and lightning-quick hooks. Meanwhile, Benitez’s radar worked so well that Cervantes’ usually pinpoint blows had a flailing look to them.

Still, Cervantes landed enough blows to raise a swelling under Benitez’s left eye but, despite the injury, Benitez maintained his technique and, most importantly, his powers of concentration. He knew that, at any moment, Cervantes could unleash a lethal blow but he didn’t allow that threat to shrink from combat. He engaged with Cervantes but on his terms. Even at 17, Benitez was smart enough to know not only how to pick his battles but also when to launch them. One of those attacks opened a cut over the champion’s right eye.

Benitez’s multi-layered style left Cervantes at a loss – and losing on the scorecards. As the fight entered the championship rounds, the only question was whether Benitez could make it to the final bell and complete the massive upset. Cervantes opened the 11th with an energetic attack but Benitez repelled it, then added insult to injury by landing several stiletto-sharp lefts, pelting him with several more blows after turning southpaw, then nailing the champion with a sharp right that drove the stunned champion into the ropes. Any doubts about Benitez’s durability, composure and moxie at crunch time were vaporized by this turn of events. The end of Cervantes’ reign was in sight – and so was the beginning of Benitez’s legend.

Cervantes launched another assault to start the 14th and, again, Benitez was up to the challenge as he neutralized the threat, then, near the end of the round, cracked the champion with a head-snapping right. Sensing the upset was at hand, ringsiders stood and cheered their hero between the 14th and 15th rounds and Benitez, convinced that a life-changing result was minutes away, expressed his joy by rolling his fists, spritely darting away and striking with superior sharpness. At the bell, Benitez visibly exhaled and initiated an embrace.

The announcement of the result was more dramatic than it should have been. The first score that was read was that of Puerto Rican judge Roberto Ramirez Sr., who saw it 147-142 for his countryman. But the other judge, Jesus Celis of Venezuela, scored it 147-145 for Cervantes (which meant that “even” won more rounds, eight, than either Benitez, five, or Cervantes, three). Such was also the case with Panamanian referee Isaac Herrera but his 148-144 scorecard officially elevated Benitez while dethroning Cervantes. A joyous Benitez was hoisted onto his handlers’ shoulders, then was fitted with a silver-colored paper crown.

In the 40 years since Benitez’s victory, several more teenagers attempted to join him. Hector Carrasquilla was just 10 days older than Benitez when he fought Soo-Hwan Hong in the WBA’s inaugural 122-pound title fight in Nov. 1977 and came tantalizingly close to becoming just the second legal minor to capture a major boxing title when he scored four knockdowns in round two. But Hong improbably stormed back in the third and left Carrasquilla flat on his back for the 10-count.

But while Carrasquilla failed, several succeeded. Cesar Polanco (18 years 83 days) defeated Elly Pical in 1986 to win the IBF junior bantamweight title while Ratanapol Sor Vorapin (18 years 192 days) dethroned IBF strawweight titlist Manny Melchor in 1992). Those who won titles at age 19 since Benitez include Netrnoi Sor Vorasingh, Morris East, Jorge Arce, Diego Morales, Koki Kameda, Hiroki Ioka, Ju Do Chun, Chul Ho Kim, Lester Ellis, Sirimongkol Singmanasak and Manny Pacquiao, who was 19 years 357 days when he stopped Chatchai Sasakul in Dec. 1998. “The Pacman,” by the way, is the oldest teenager ever to win a belt.

Trivia question: Who was the youngest champion crowned in the 21st century? The answer: Marvin Sonsona, who was 19 years 46 days old when he decisioned Jose Lopez to win the WBO junior bantamweight title in Sept. 2009. He is the ninth youngest boxing titlist on record.

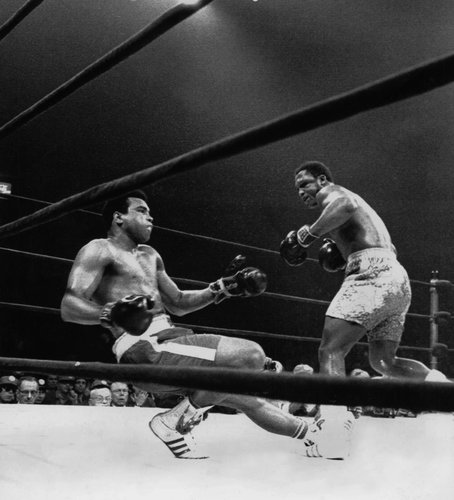

I wasn’t yet a boxing fan when Frazier first met Ali at Madison Square Garden 45 years ago. I was a carefree six-year-old about to start kindergarten but the boxing world that surrounded me figuratively stopped on its axis as it awaited not just a clash of two great fighters but also two diametrically opposed ideologies. Politically speaking, Ali, who was stripped of his championship due to his refusal to be drafted into the Vietnam War, was the icon of the counter-culture left while Frazier, mostly by default, was cast as the representative of the “hard hats” that supported the war effort as well as the social status quo.

In sporting terms, however, Frazier-Ali I was as good as it got. On paper, both were undefeated fighters with a legitimate claim to the world heavyweight championship. Ali never lost his title inside the ring while Frazier, in Ali’s absence, first won the vacant NYSAC version of the belt by knocking out Buster Mathis Sr., then pulverized Jimmy Ellis, who out-pointed Jerry Quarry to win the WBA’s eight-man tournament, to acquire “universal” recognition. But Frazier and his management knew he’d never be fully accepted as champion until he beat Ali. Stylistically, the two couldn’t have been more different; at his best, the 6-foot-3 Ali possessed lightning hand and foot speed, a swift and prolific jab and an immense pride that fueled his considerable competitive streak. On the other hand, the 5-foot-11 1/2 Frazier’s energetic bob-and-weave and punishing body attack beautifully set up his ferocious left hook, arguably boxing history’s single most potent weapon. Of his 26 victories, 23 were by knockout.

During Ali’s exile, Frazier occasionally loaned money to the ex-champ while also championing his cause to various boxing authorities. Ali eventually won reinstatement in 1970 and following wins over Quarry (TKO 3) and Oscar Bonavena (TKO 15) “The Fight” was finally made for March 8, 1971 at Madison Square Garden.

The atmosphere was electric and, thankfully for boxing, so was the fight. Both men more than earned their $2.5 million paychecks and the fight featured several distinct shifts of momentum. Ali dominated the early stages with his rapier jab and swift combinations while Frazier controlled the middle stages by trapping the shockingly immobile Ali on the ropes and punishing him with hammering hooks and sticky body shots. Ali briefly breathed deeply “in the zone” in round nine as he nailed Frazier with a series of clean blows but Frazier turned the tables in the 11th when a massive hook nearly floored the ex-champ. Ever resourceful, Ali instantly shifted into showman mode and his outrageously exaggerated wobble convinced Frazier to hold back just long enough for Ali to regain his bearings.

Photo credit: United Press International

Ali and Frazier continued to punish each other in the 12th, 13th and 14th but early in the 15th, destined to be named THE RING magazine’s Round of the Year, the native South Carolinian-turned-Philadelphia hero transformed himself into a fistic icon when his trademark hook struck Ali’s already swollen jaw and drove the former champion to the canvas. The flushness, leverage and pinpoint location of that particular hook would have rendered most fighters unconscious but Ali, defiant to the end, somehow scrambled to his feet at referee Arthur Mercante’s count of four. Overcome by fatigue and pain, both coasted to the final bell and, in the end, Frazier was awarded a decisive unanimous decision. This “Fight of the Century” easily exceeded its two predecessors (Jack Johnson vs. James J. Jeffries and Jack Dempsey vs. Georges Carpentier), for it was named THE RING’s Fight of the Year and earned Frazier his second consecutive Fighter of the Year award from the magazine. It would be his third – and final – such award, while Ali would go on to win his second (1972, an award he shared with Carlos Monzon), third (1974), fourth (1975) and fifth awards (1978). Only Joe Louis (four awards), Rocky Marciano (three), Evander Holyfield (three) and Manny Pacquiao (three) have won more than twice.

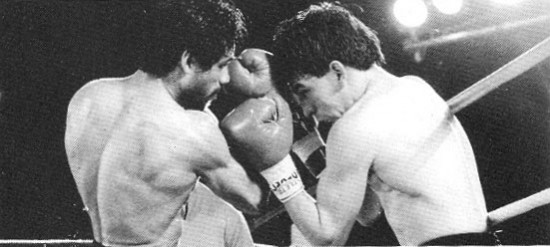

Because pay-per-view had not yet reached Friendly, I didn’t get to see Showtime’s inaugural card live but rather saw the delayed broadcast on the premium channel. Back then, I had a giant C-band dish that zipped from satellite to satellite thanks to a rotor set up by my electronically gifted uncle. And what a card it was: On March 10, 1986, Richie Sandoval was scheduled to defend his WBA bantamweight title against top contender Gaby Canizales while Thomas Hearns challenged James Shuler for his North American Boxing Federation (NABF) middleweight title. The main event had Marvelous Marvin Hagler defending his undisputed middleweight championship for the 11th time against power-punching Ugandan John Mugabi, who entered the ring with a monstrous 25-0 (25 KOs) record.

While Sandoval-Canizales was to serve as an appetizer, the real thrust of this card was to set up a potential rematch between Hagler and Hearns, which was tentatively set for Sept. 1986. Eleven months earlier, “The Marvelous One” and “The Hitman” set the sports world alight with their titanic three-round slugfest and, entering this night, the two A-side fighters were expected to clear their respective hurdles. Though the 22-0 (16 KOs) Shuler shared Hearns’ 6-foot-1 height and 78-inch reach, he lacked Hearns’ pedigree and vaporizing power, while Mugabi, despite his intimidating record and brooding monosyllabic persona, was thought to be too crude to handle Hagler’s multi-dimensional skill set.

Leading off the evening was Sandoval and Canizales. Sandoval stunningly won the title from long-reigning champion Jeff Chandler with a 15th round TKO that capped an overwhelmingly dominant performance but, in the 23 months since, he defended only twice (UD 15 Edgar Roman, TKO 8 Cardenio Ulloa). Since the Ulloa bout, nearly 16 months earlier, Sandoval had fought four 10-round, over-the-weight bouts against Frankie Duarte, Jose Gallegos, Diego Avila and Hector Cortez. Alarmingly, Sandoval scaled 127 ¾ for the Cortez fight, which took place just 31 days before the Canizales defense.

According to manager Tony Cerda, Sandoval’s weight loss was gradual and safe.

“He lost 2 ¾ pounds per week,” Cerda told the Los Angeles Times’ Richard Hoffer. “The night before the weigh-in, he shadowboxed for five rounds and jumped rope for 15 minutes and was about 119.” Though Sandoval scaled 117 ¾, his physique looked pale and bony while Canizales, despite weighing a shockingly low 116 ¾, appeared coiled and ready to strike.

Throwing little more than a jab and unable to exhibit his usual mobility, the weakened Sandoval had little choice but to engage with the more powerful challenger. Sandoval was floored in rounds one and three before three more knockdowns ended matters in the seventh. Canizales’ savagery was such that analyst Gil Clancy compared the challenger to the prime Roberto Duran. Unfortunately, the results of Canizales’ final assault plunged Sandoval into a crisis that threatened his very life.

According to the Times, Sandoval stopped breathing for 90 seconds and was unconscious for 14 minutes. During that time Doctors Donald Romero and Flip Homansky as well as neurosurgeon Dr. Kazem Fothie attended to Sandoval. Romero inserted an airway to help restore Sandoval’s breathing and after the ex-champ was stabilized, he summoned paramedics to carry Sandoval out on a stretcher and load him into an ambulance, which was parked 20 yards away. Sandoval never fought again.

But while tragedy was averted for Sandoval, such was not the case for Shuler, who Hearns knocked out with a right hand just 73 seconds after the opening bell. While the man named “Black Gold” walked out of the ring under his own power and was gracious enough to come to promoter Bob Arum’s hotel room to thank him for the opportunity, the fighter’s life ended just seven days later. According to George Azar’s story in the Philadelphia Daily News, Shuler was riding a Kawasaki Ninja motorcycle he purchased with part of the Hearns’ purse. Traveling at a high rate of speed and without the proper license, Shuler lost control and skidded approximately 50 feet into the path of a truck going the opposite direction. In that instant, 26 years of life as well as a promising future was snuffed out.

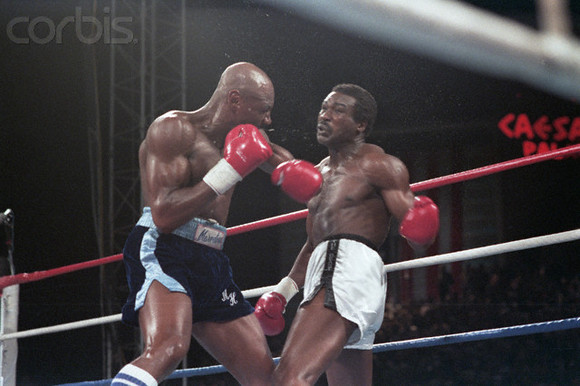

After Hearns easily fulfilled his part in creating Hagler-Hearns II, he arrived at ringside to see if the longtime undisputed champion would close escrow on his. He would – but it wasn’t easy. Thought to be a crude bomber, most believed Mugabi would be sliced and diced before being sent into oblivion but, to the shock and delight of many, the Ugandan raised his game several levels and pushed Hagler harder than most. His heavy blows regularly clanged off Hagler’s dome, from which came white vapors due to the 51-degree temperature at Caesars Palace’s outdoor arena and the sixth round produced breathtaking back-and-forth action.

Photo courtesy of Corbis

With his right eye badly swollen and the result still in the balance (Hagler led 97-94 on two cards and 96-95 on the third, despite a one-point penalty for low blows in the seventh), the champion dipped into his reservoir of greatness and produced a finishing surge. Two big rights sent a tired and somewhat discouraged Mugabi to the canvas, where he stayed for referee Mills Lane’s 10-count.

“I thought I had him KO’d in the sixth round when the referee stepped in,” Hagler said. “It’s tough to KO a guy when he’s in good condition. I had to change my strategy, work inside, wear him down, use my jab, combinations, go to the body.”

Mugabi, despite his first loss, considered himself to be an even more dangerous force than he was before the bout.

“I got experience now,” he said.

The anticipated Hagler-Hearns rematch never happened, for there was someone at ringside that night who was convinced he could change the course of history with a single phone call. That man proved to be right, for his name was Sugar Ray Leonard.

What would have happened had Leonard remained on the sidelines and Hagler-Hearns II took place as scheduled? I believe that Hearns, coming off a powerful KO win and, at 27, was still in the midst of his physical prime, would have opted to employ a far more intelligent strategy: Impale Hagler with his piston-like jabs, land just enough right hands to earn the champion’s respect and keep the fight at long range from first bell to last. Hagler, now 32 and worn down somewhat by the Mugabi match, would have been troubled by Hearns’ movement just as he was actually flummoxed by Leonard’s in April 1987. With Hearns on the move Hagler would have had no choice but to charge in, which would have played right into The Hitman’s hands because, this time, Hearns would be setting the terms. Without the element of surprise, as was the case when Hagler charged out at Hearns in fight one, Hearns would win on points.

*

Along with pondering boxing history, I spent much of the drive listening to the radio and when I couldn’t find any alternatives when the various stations faded out, I opted to let my thoughts entertain me. Despite the long drive, there were no major issues regarding congestion or driver misbehavior and I pulled into the Courtyard Marriott’s parking lot precisely at 7:30 p.m., the time I thought I would arrive once I left home. If I’m nothing else, I’m dependable and predictable when it comes to driving time.

I spent much of the evening relaxing and watching TV in the hotel room, though I bought a snack from the mini-mart by the registration desk around mid-evening. As is the case most evenings, the urge to sleep came gradually and by 1 a.m., I was ready to click off the light.

Saturday, March 5: The long drive must have worn me out because I slept for a solid six-and-a-half hours. Feeling refreshed, I spent most of the morning and several hours in the afternoon catching up on my writing responsibilities, then, shortly before 2:30, I headed out toward the Sands Resort and Casino. Meanwhile, my colleague Andy Kasprzak was making the five-hour drive from Massachusetts and, following his mid-afternoon arrival, he rested for a few hours before coming to the arena. As I waited, I chatted with Executive Producer Gordon Hall about the televised portion of the card. He was eager to discuss the particulars of each match-up and he did so with extraordinary depth and detail. He rattled off factoids about all six fighters, including who they defeated in the amateurs, the simon pure titles they won and their recent bouts with enviable fluidity. I was deeply impressed with his expertise.

Andy and I decided to count two of the untelevised undercard bouts – Ievgen Khyrov’s 10-round decision win over Kenneth McNeil and the Joey Dawejko-Ytalo Perea eight-round draw – both of which would have made an excellent ShoBox telecast as well. While the verdict favoring Khytrov was lopsided (99-91, 97-92 twice) and the statistics equally dominant (310-176 overall, 94-54 jabs, 216-122 power), the Ukrainian prospect had to compete with a severe cut around the left eye from round three onward. Instead of letting the blood bother him, Khytrov continued his pressuring tactics (he averaged 94.7 punches per round to McNeil’s 55) behind an effective jab (9.4 connects per round). He also topped the 100-punch mark four times, including 111 in the final round. Khytrov showed the mental strength to cope with adversity in a positive manner, a trait that surely will benefit him in future fights.

As for Dawejko-Perea, the first two rounds were fun to watch as Dawejko fired fast, powerful blows that caught the New York-based Ecuadorian flush while Perea, who took the blows with barely a flinch, responded with accurate jabs and precise counters. The pace slowed markedly from round three on but Dawejko compensated for his 32.1-punch-per-round pace with extraordinary accuracy (55% overall, 41% jabs, 65% power) while the more active Perea (44.4 per round) managed to force Dawejko onto the back foot at times and more than held his own in the skirmishes. The final numbers were close (Dawejko led 141-132 overall and 95-84 power while Perea prevailed 48-46 in landed jabs) and the judges concurred (78-74 Dawejko from Waleska Roldan, 77-75 Perea from Adam Friscia and 76-76 from Tom Schreck).

The final undercard bout ended 45 minutes before airtime, which gave me plenty of time to chat with several ringside reporters like Ken Hissner as well as talking history with Andy, always an enjoyable endeavor. Once 10 p.m. arrived, Andy and I were ready to roll.

*

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, West Virginia. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 13 writing awards, including 10 in the last five years and two first-place awards since 2011. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. Groves is the author of “Tales from the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics.” To order, please visit Amazon.com. To contact Groves, use the e-mail [email protected].