The pride of the Fighting Matthysses – part two

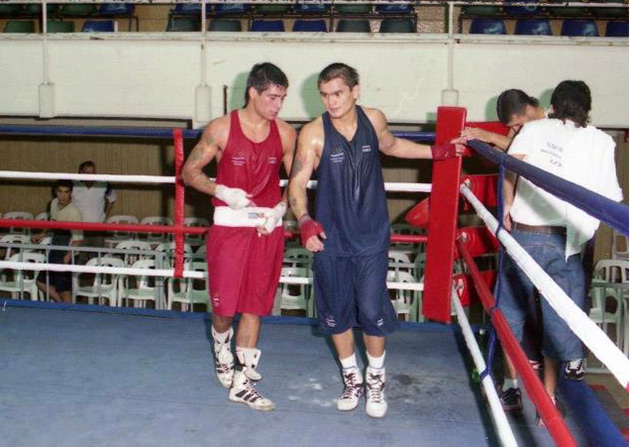

Lucas Matthysse and Marcos Maidana fought four times in the amateurs and they aim to make it five with a mega-showdown as pros. Source: Lucas Matthysse Facebook page)

Click here for part one.

The long road to Peace and Hope

Leaving home on a quest of soul-searching is a rite of passage that very few teenagers force themselves to endure. And when they do it in search for a career in a sport as difficult and dangerous as boxing, you are forced to take notice about the seriousness of their intentions.

Beset on both sides by the overprotection of his mother and the perfectionism of his father, Lucas Matthysse left his home looking for a place to hone his skills, and soon he found it in a small town near his dad’s birthplace.

Soon enough, he also found another partner in crime with his same intentions, a young kid who wanted to make it big in boxing, just like him.

His name? Marcos Maidana.

“If we both move to 147 pounds we’re going to get that offer, because we’re going to be in the same weight and they’ll offer the fight to us,” says Matthysse, about his former roommate, sparring partner, and even occasional opponent in his amateur days. “In the sport side of things, I would love to fight him, because this is a sport. But we’re going to leave the ring embraced”.

Maidana and Matthysse met while living under the same roof in the small town of Vera under the guidance of Juan Keller, a local trainer who owned a small produce distribution warehouse and who soon became his mentor. Matthysse remembers those seminal years very fondly.

“Those people gave me everything, and I was with them almost two years,” says Matthysse. “We all lived in his house. He had a truck and we would go sell groceries from town to town, and we’d carry our punching bags in the truck to hang them from trees by the road, or we would go to wherever there was a fight card to try to get a fight.”

Juan Keller’s own recollections confirm Lucas’s memories.

“I had him as an amateur, for about one and a half years. In the year 2000 I took him to the Argentine Championship, and he got the title. He was 18,” says Juan, who is not involved in boxing anymore. “Lucas had 18 fights with me. He had one draw and the rest of the fights he won.”

Despite the bleak nature of the humble surroundings, Lucas’ dedication was already in full display.

“He was very respectful, and he was addicted to the gym. Very addicted. We used to learn from him. Maybe not as (dedicated as) he is today. He was a little bit lazier, but now I see that he is well advised, well trained. We were a family. He was one more son to us,” says Juan.

In the distance, Matthysse agrees.

“Even when they had their own kids, they gave me everything, and supported me a lot. When I went to live in Buenos Aires we separated, but I always told them I would love to see them again one day, because they opened their home to me and gave me everything.”

Keller’s prognosis, however, stretches much further into the horizon.

“I believe he’ll become our biggest fighter. The way he’s training now, and the way his mindset has developed, his hunger. I see it when he goes into the ring with that hunger, with that passion. ┬┐Who could possibly handle this crazy guy, with the way he’s training now?”

The Brotherhood of the Ring

“Walter is Lucas’ biggest idol,” states trainer Cuty Barrera, matter-of-factly.

As a young, tough welterweight with movie-star looks and a hammer in each hand, Walter was the first of the Matthysses who ever gained any real notoriety when he was signed by Golden Boy and engaged in a series of high profile fights in the early 2000s. He was expected to become a top contender, with his blonde-hair, blue-eyes looks and Latino fighting style, and he was being groomed for stardom.

But something went terribly wrong when Walter took the long-awaited step-up in competition. He took his 25-0 record to California, in his first fight away from home, and put it all on the line against one of the most avoided fighters of the time in future two-division titlist Paul Williams, who handed him a tremendous beating before a 10th-round stoppage in 2005. The Williams beating took its toll on Walter, who apparently was never the same after that fight. He would end his career three years later after a 1-4 streak, with all of his losses by stoppage. The fact that three of those losses came against such fighters as former champ Kermit Cintron (in a title fight), and top contenders Sebastian Lujan and Alex Bunema did little to hide the fact that the career of the man they called “El Terrible” had fallen into a downward spiral.

“I think (Walter’s decline) strengthened Lucas,” said Barrera. “Seeing his brother like this, it made him train harder, much harder than Walter. I wasn’t with Walter and I don’t know much about his entourage, but I know Walter had some very tough fights. I know that if Walter would hit them, they’d go down. That’s when you see they have the punching power in the blood.”

That may be the case, but while Walter’s power was his trademark (having scored 25 KOs in 26 victories), Lucas became more of a reluctant KO artist, trying to honor the family name by mowing them down as soon as he could, but also trying to put money in the bank by getting his boxing together and becoming more of a complete fighter.

“I think he doesn’t want to go through what Walter went through,” says Barrera. And so far, Lucas has succeeded.

But that success has come with a price. An emotional price that Lucas is still trying to pay.

“I learned that I have to be well prepared all the time. I used to admire him a lot,” says Matthysse, starting the phrase in a firm tone that degrades into the soft moan of a painful memory, all while pretending to be removing a pesky piece of debris from his eye even though he is clearly and literally holding back a tear.

“I used to follow him everywhere, and I still do. But I did learn I have to train more. Because that’s what I saw in my brother, that he could have gone very far, but since he didn’t train as hard as he used toÔǪ,” says Matthysse, in an unfinished sentence that suddenly becomes one of his most eloquent statements.

Walter himself, now working as a security guard in the state legislature of his province, has no problem admitting that he and Lucas have passed each other in the race towards mutual idolatry.

“When I debuted as a professional, I was his idol, and now is the other way around. We are always admiring each other,” says Walter. “We were always together. First, it was me who started out, and he followed my steps. He had the good luck of being good friends with Marcos Maidana when he was starting out as an amateur. He became part of the Argentine national team, and that’s when he became my idol.”

That particular experience of having the time to work on his skills as a young man, with no other worries in the world, is what set Lucas and Walter apart.

“In the national team is where he learned the most, because he traveled to Cuba, to many different places, and the truth is that the national team has developed him into what he is now,” says Walter.

Even so, neither one of them would refuse to admit the power of their DNA when it comes to their natural skills.

“From my father, he took the boxing skills. They say my dad was an excellent boxer. Then, Lucas learned to hit the body thanks to me, because whenever we sparred I would hit him downstairs and made him feel my power, and when you spar and you feel the pain you end up imitating that same technique that hurts you.”

Walter’s best days are gone indeed, but now there may be another member of the family who could join both Lucas and Walter in this race of mutual admiration.

“He was here with me, training with the rest of the guys, and he has a lot of conditions,” says Lucas about his nephew, 17-year-old Ezequiel, currently training in the US under Robert Garcia in Oxnard, California, and the tallest one of the trio so far at 6 feet. “He is on the rise, and I hope to bring him here (to Junin) to learn more.”

“He has my punching power, and also he has Lucas’ boxing skills. He has it all. He used to train with Omar Narvaez from 8 to 10, go to school in the afternoon and at 7 pm he is back in the gym,” says Walter.

The Narvaez are also an extended part of the family. Omar (a recently dethroned junior bantamweight titlist after a long reign as a flyweight champ) and his brothers Mario (a brother-in-law to both Walter and Lucas thanks to his marriage to Soledad) and Nestor (a contender who used to train with Lucas in Vera as part of Juan Keller’s stable) live all within a few blocks from each other, and they became part of the extended brotherhood that now includes three generations if we count Mario Matthysse and his continuous presence at the Narvaez gym.

“We always hang out together. I live one block away from Omar Narvaez’s gym. My son trains in that gym. We’re constantly there,” says Walter, who now includes the Narvaez’s in the “lucky group” they put together to watch whoever else is fighting. As it is customary in Argentina, fans get together in the same group and seat in the same seats every time there’s a game or a fight.

The plan for this Saturday, then, is already on, according to Walter.

“We get together in my house. We barbecue, and then we celebrate Lucas’s victory.”

Wild bull, reloaded

The painting still hangs in the Whitney Museum in New York, and it is about to turn 90 years old.

Its official name is “Dempsey and Firpo,” but most people know it as “Dempsey through the ropes.” Its author is George Bellows, and the work is considered “the greatest American sports painting,” and it depicts Luis Angel Firpo, a towering Argentine heavyweight, as he sends then-champ Jack Dempsey flying through the ropes and onto a typewriter in press row.

The fact that Dempsey rose to get back into the ring and beat Firpo one round later to retain his belt is lost in the picture. But there is still time to paint a new masterpiece, and for that, Matthysse is betting on some of Firpo’s mojo rubbing off on him.

After years of globetrotting, torn between choosing mom or dad, Hope or Peace, Matthysse has now settled in the small town of Junin, where Firpo was born some 120 years ago to become the first notorious fighter in a history that now includes names such as Carlos Monzon, Nicolino Locche, Victor Galindez, Sergio Martinez. A list that Lucas hopes to join one day.

“I love to box, and I think I can do it well. I like to punch, slip punches, counterpunch. In these fights I go forward all the time, but I’d like to show a few more things as well,” says Lucas.

Whether he manages to send Provodnikov flying through the ropes is yet to be seen, but in his own silent way he appears to have the same confidence that carried him through the most difficult fights of his career.

“I believe each fight has been important,” said Lucas. “With (DeMarcus) Corley I had a great fight. Even though I sent him to the canvas like 8 times he was a very experienced guy who complicated Maidana in his previous fight, and winning the way I won gave me a lot of experience. (Lamont) Peterson was the best in the division. A big commitment. I was surprised to win the way I did. I am loosening up more and more in every fight, and you could see that with Peterson. I get more confident and loose in the ring with every fight. And I gain confidence in every aspect, knowing that with every opponent I feel more and more confident.”

So big is his confidence, that even through the heartbreaks of his two defeats he has learned a hard lesson in reassurance.

“I believe experience was the key word,” said Lucas about his fights with Zab Judah and Devon Alexander, two close points defeats that earned a lot of attention. “I was fighting around Argentina, and going over there to fight Judah, a three-time world champion, was not just any fight. Nevertheless it was a good fight, and I think I won. Same with Alexander. I came out with a different rhythm, but they robbed me anyway. And from there on, I came out feeling better and better for every fight.”

His trainer can only agree, but not without taking some of the credit for a serious and long-awaited pep talk.

“We spoke to him, and we told him he has to be more of a boxer than a fighter. In the U.S., if you don’t throw a lot of punches you’ll never win. We started working more with power and speed. He started adding crosses and volleys, and the results were evident. We all know he has speed, and he can punch and box. He started to feel comfortable blocking punches, but he had to work with his waist a little bit more.”

Lucas learned that lesson the hard way, and paid with bitter tears in his most painful defeat in recent times.

“I feel I did everything OK, but they stole the fight from me,” says Lucas, in regards to his defeat at the hands of Zab Judah in his first title shot, back in November of 2010. “That hurt a lot, because I couldn’t bring the title home. Losing was painful, but not getting the title was even worse.”

But against Provodnikov, Lucas is betting on a different strategy, one that could help him honor his new, unexpected nickname.

“In my fight against (Lamont) Peterson, someone (Note: ring announcer Jimmy Lennon Jr.) came up with that name. I heard it for the first time right there in the ring,” says Lucas, henceforth also known as “The Machine.”

If things go as planned, it won’t be the last. And he’ll have plenty of time to hear it in the ring and make it his own.

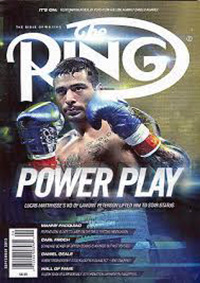

The illustrated men

In the long history of Argentine boxing, only a handful of fighters have made it all the way to the cover of THE RING magazine, and they all have reached that milestone after numerous achievements and accomplishments. The fact that Lucas Matthysse has already been featured on the cover of the venerable publication serves to illustrate not only his present achievements, but also the tremendous expectations placed on him, and the way the boxing world feels about him.

But Lucas is no stranger to seeing his feelings in print.

“I haven’t done one in a long time,” says Lucas about the many tattoos that populate his skin, most of which are self-inflicted. “I started with a little heart here in my hand, and later when I was in the national team I tattooed everyone,” says Matthysse, listing a few names such as current junior flyweight titlist Juan Carlos Reveco, Maidana, Sergio Martinez, and many more. “I put together an improvised little machine and started learning, first on myself and then with others”.

That obsession with being his own man, with leaving his own mark on the world and on himself, with being the one Matthysse to make it to the top on his own terms, is reflected in his training and in his boxing style. And that same obsession is the reason why he has so few role models in boxing. He does mention Manny Pacquiao and Juan Manuel Marquez with a special reverence, and his deep respect for every last one of his peers in the extended Brotherhood of the Ring is always evident in his words. But it is clear that he’d rather not be “the next Monzon”, or the “pocket Bonavena.” He probably doesn’t even want to be the second Matthysse to make it to Las Vegas. He wants to be the first Lucas, even though he knows he lacks the likeability factor of another one of his friends and compatriots, one of the sport’s true rock stars.

“I sparred with him through his entire training camp,” says about his relationship with middleweight champ – and fellow RING magazine cover fighter – Sergio Martinez. “It was a great experience seeing him train in the morning, seeing all his sacrifice, and following him up in his sparring sessions. We had a great time, I learned how to fight southpaws a little bit, and he would explain things that he doesn’t like. He is more popular and more talkative than me, but I think that if I win this fight it will be my moment, and people will start to know me more and more.”

Unlike Martinez, who splits his time between California, Madrid and Buenos Aires, Lucas’ life is already settled in that remote corner of the world in which he found the Peace and Hope that led his ancestors away from their land forever. But just like his mother, he is torn between his home in Junin and his daughter Priscilla who still lives in Trelew. He finds his way to that southern town in the barren Patagonia coast very often to see her, and keep an ear open for a piece of advice from that stubborn old Dutch father of his whenever he goes there.

Still, he finds the most peace in the simplest possible things.

“I want to learn to play guitar. I am already taking lessons. I have my dogs, three pit bulls. I like to hunt sometimes. And I also go to fish in the ocean”.

His fishing and hunting trips are optional, but his long journey into boxing stardom has the air of inevitability that drove his folks to cross the many rivers and oceans they crossed, and the thousands of miles they traveled to set foot in the land of Peace and Hope. A road that now takes him to the farthest northern place he’s ever been in search for a new chance to crown himself as champion.

In this trip, just like in any other trek of the Matthysses and the Steimbachs of old, Lucas will be riding on his hunger, his flag, his soul and his spirit towards the most important battle of a struggle that began many years ago, with a different trip into an unknown land.

And just like his old folks did it, Lucas will be betting on putting all of this together, along with the stubbornness of the Netherlander peasant, the undying esperanza of the German nomad, the heart of the Argentine wild bull and the pride of the Fighting Matthysses, in his bid to become junior welterweight champion and leave his most definitive mark in the world of boxing so far.

And you can count on a commemorative tattoo being already designed for that special occasion. Both for him and for his rivals, and the collective memory of the boxing world.