George Foreman’s KO of Michael Moorer remains special 20 years later

[springboard type=”video” id=”1124333″ player=”ring003″ width=”648″ height=”511″ ]

It wasn’t supposed to happen, but when it did the world rejoiced. For George Foreman, the man who made it happen, a torturous circle had closed.

Twenty years ago today, a crisply delivered one-two drove lineal heavyweight champion Michael Moorer to the floor, ignited explosive cheers that tested the MGM Grand’s foundation and allowed Foreman to shatter records, annihilate conventional wisdom and exorcise two-decade old demons.

At 2:03 of round 10, Foreman’s pursuit of reputational redemption and earthly catharsis was completed. His nightmare began the moment Zack Clayton waved his arms over a defeated Foreman in Kinshasa, Zaire and ended the instant Joe Cortez bellowed “10” over Moorer. In recognition of his struggle, Foreman wore the same trunks for both fights. However, the men who filled them couldn’t have been more different.

*

During Foreman’s first championship reign he ruled with iron fists that struck with murderous intent and projected a menacing aura that intimidated most who dared to approach. His 220-pound physique was muscular but not muscle-bound, for he was capable of unleashing dozens of bombs per round. Few could withstand his punishment for long; coming into “The Rumble in the Jungle” Foreman’s 40-0 (37) record included 21 knockouts in two rounds or less. In his title fights against Joe Frazier, Joe Roman and Ken Norton Foreman scored 12 knockdowns in 14 minutes 26 seconds. That destructiveness led many to fear for Muhammad Ali’s life but Ali’s imaginative mind conjured the “rope-a-dope” that led to Foreman’s defeat.

To Foreman, the Ali loss not only stripped away the championship but also destroyed his sense of manhood. In his mind, the only way to regain all he had lost was to win back the title.

“There’s something within me that moves me to become heavyweight champion of the world,” he said. “And I won’t stop until I satisfy this thirst within me.”

Ali’s manager Herbert Muhammad offered a rematch on the condition Foreman re-sign with Dick Sadler, with whom he had been working without a contract since the Frazier fight. Foreman refused. He figured he’d earn another chance the old-fashioned way – by earning it.

His journey didn’t begin well. On April 26, 1975 in Toronto Foreman staged a nationally televised exhibition in which he faced five opponents in a series of three-round bouts. In 12 rounds of sometimes farcical action, Foreman stopped Alonzo Johnson, Jerry Judge and Terry Daniels while battering Charlie Polite and Boone Kirkman over the distance. Although the event was an exhibition the action was all-out. The warfare dented Foreman physically – he suffered a cracked rib – but inflicted even more damage psychologically because Ali, as ABC’s color commentator, hurled countless verbal arrows and egged on the already-hostile crowd. Ali instructed Foreman’s foes to lay on the ropes and Foreman’s bullying prompted vociferous boos more suited to pro wrestling. An event designed to restore his superman persona couldn’t have produced a worse PR result. Instead of reverence, Foreman was ridiculed.

Foreman’s first official match after the Rumble was against Ron Lyle in January 1976. In one of history’s greatest slugfests, Foreman climbed off the deck and battered Lyle into submission in round five.

[springboard type=”video” id=”1124381″ player=”ring003″ width=”648″ height=”511″ ]

Foreman consolidated that performance with knockouts over Frazier, Scott LeDoux, John Dino Denis and Pedro Agosto. Those results set up a meeting with Jimmy Young, whose spotty 20-5-2 (7) record and feather-fisted blows led many to believe Foreman was one step away from an Ali rematch.

An overconfident Foreman thought he could squash Young at will so he intended to prove a larger point – that he could fight well from first bell to 12th. Foreman nearly bagged Young in the seventh but the wily Philadelphian’s resourcefulness pulled him through. Foreman’s arm-weariness helped Young regain confidence, then control in the later rounds. A flash knockdown in the 12th turned a potential majority decision into a unanimous one for Young, who went on to meet Ken Norton for what became the WBC title two fights later. As for Foreman, a life-changing experience awaited.

In his dressing room Foreman felt a crushing void he perceived as death. As he tells it, the moment he said “I don’t care if this is death. I still believe there’s a God,” a giant hand lifted him out and breathed new life into him. Trainer Gil Clancy dismissed this episode as heat prostration but to Foreman it was transformative.

For the next decade Foreman, now an ex-fighter, circled the globe and preached the Gospel. He became an ordained minister in late 1978 and opened a youth center bearing his name. Not only was he a different man spiritually and verbally – his new-found faith unearthed previously untapped oratory skills – he also was a changed man physically. He shaved his head and added more than 100 pounds. Boxing was the furthest thing from his mind until an incident at a Georgia evangelical conference changed his thinking.

“For three days I spoke and met the people attending,” Foreman wrote in his autobiography By George. “These were just regular people, most of them poor. At the end of the conference the organizer rose and described the good work being done by the George Foreman Youth and Community Center. I smiled proudly until he turned the address into a request to dig deep for donations.

“‘We’re going to raise some money for George,’ he said. ‘He’s helping these kids, our kids.’ I thought about becoming invisible. And it got worse. ‘Come on,’ he pleaded as the cash got passed forward. ‘You can give more money than that. You help George, for our kids’ sake.’ They were looking at me, and I had to look back at them, and pretend I wasn’t ashamed.’ I vowed at that moment, sitting on a hard bench in front of those people, that as long as I lived I would never again be involved in a stunt like this. Yes, those kids needed me, and I wouldn’t desert them. I’d just have to find another way to raise funds.

“And then the thought struck me: ‘I know how to get money. I’m going to be heavyweight champ of the world. Again.'”

*

At best, Foreman’s quest seemed a fool’s errand while at worst it was a death wish. At 38 Foreman was obese, carried mountains of ring rust and felt guilty every time he hit someone. While Foreman addressed these issues in the gym and within his soul, he also needed to convince authorities he was fit to fight. Although he passed the mandatory exams the California commission initially denied Foreman a license because of his age. With the help of a lawyer from the attorney general’s office, Foreman was granted the privilege to try.

Unlike most ex-champions Foreman didn’t seek an immediate title shot, which, at the time of his application, meant meeting IBF titlist Tony Tucker, WBA kingpin James “Bonecrusher” Smith or, worst of all, WBC champion Mike Tyson. Instead, he treated himself as a prospect who needed time to develop. On March 9, 1987, two days after Tyson united two of the belts by out-pointing Bonecrusher, Foreman met journeyman Steve Zouski at Sacramento’s Arco Arena.

When Foreman announced his return, he was greeted with skepticism, concern and scornful laughter. Those sentiments were stoked when Foreman scaled an unbecoming 267 pounds. Zouski, a 33-year-old who had gone 2-9 with five KO losses in his last 11, seemed a suitable foe.

[springboard type=”video” id=”1126207″ player=”ring003″ width=”648″ height=”511″ ]

The crowd gave Foreman a standing ovation when he entered the ring but once the bell sounded Foreman’s humanity struggled with the demands of his job. He stopped Zouski in four but the end was primarily the result of attrition. The $21,000 check helped assuage some of the negativity.

Four months later Foreman stopped Charles Hostetter in three. From there Foreman halted Bobby Crabtree in Springfield, Mo. and Tim “Doc” Anderson in Orlando, Fla. to set up the comeback’s first nationally televised fight against Rocky Sekorski in Las Vegas on ESPN.

Weighing a trimmer 244, Foreman had also sharpened his messaging. When he wasn’t joking about his girth and his craving for cheeseburgers, Foreman was declaring that “40 isn’t a death sentence” and that age shouldn’t impede one’s pursuit of dreams. His entrance music was Lee Greenwood’s “God Bless the U.S.A.” and his new persona was a hit with both the live audience and the cable universe. The crowd inside Bally’s Las Vegas was so large that hundreds of extra chairs were added and fire marshals turned away hundreds more.

Foreman showed himself to be a far different fighter than the out-of-control bomber that wreaked havoc in the 1970s. This Foreman operated behind a thumping jab and exercised a level of patience that his younger self couldn’t have understood. When Foreman turned up the heat, he delivered tightly-arced, heavy-handed blows that snapped heads and swiveled necks. A series of unanswered punches prompted Richard Steele to intervene at 2:48 of round four.

With a relaxed, smiling Foreman standing at his side (and cowering in mock fright), Sekorski lent verbal credibility to his conqueror’s comeback.

“I’ve fought lots of people, all the champions in all the countries; I feel he is one of the best punchers I’ve fought,” he said. “I believe he would beat (Francesco) Damiani, (Adilson) Rodrigues, Pierre Coetzer, all those other (guys) I’ve fought. I believe he may knock them out.”

“I’ve got more skills than I’ve ever had in my life,” he told a doubtful Al Bernstein. “I’m having fun in there. There’s no edge, (I’m) playing with the stool, talking to my corner men, enjoying the fight. I didn’t really want the fight to end quickly, although it was good that the referee stepped in. The George Foreman of 10 years ago felt this (boxing) was a horror house but now I’m having lots of fun. Ten or 15 years ago my best friend was a dog. Now I’ve learned that the best invention in the world are human beings. I love being around them; I want to smile and say hello because you never know when you’re going to meet them again. So I’m enjoying being around people now. Man’s best friend is man.”

The public clamored to see more of the old man with the new attitude. In 1988 Foreman went 9-0 (9) and traveled to Florida twice, Nevada twice, New Jersey, Michigan, Alaska, California and his hometown of Marshall, Texas. The next year saw him rack up four more knockouts before Everett “Bigfoot” Martin ended Foreman’s KO streak at 18.

The turn of the decade brought demands for better opposition. Thus far the biggest names Foreman beat were a bloated Dwight Muhammad Qawi (KO 7), former light heavyweight titlist J.B. Williamson (KO 5), a less-than-formidable Bert Cooper that retired on his stool after two rounds, and Martin. As usual, Foreman replied with a joke.

“Some say I don’t fight any guys unless they’re on a respirator,” he said. “That’s a big lie. They have to be eight days off the respirator.”

Still, interest was building in a Tyson-Foreman fight for what now would be the undisputed championship. But first Foreman had to beat a credible name.

Gerry Cooney might not have been a suitable foe in terms of resume – he hadn’t fought since Michael Spinks leveled him two-and-a-half years earlier – but he was a giant in terms of size (6-foot-6, 231 pounds) and marquee value. Their showdown was derisively dubbed “The Geezers at Caesars” but Foreman’s two-round destruction was so impressive that he was regarded as a viable option for Tyson, at least as far as generating a monstrous purse.

It wasn’t to be. Twenty-seven days later in Tokyo Tyson lost to 42-to-1 underdog James “Buster” Douglas, who then lost to Evander Holyfield. Meanwhile Foreman stopped Mike Jameson and Ken Lakusta on USA’s Tuesday Night Fights, Adilson Rodriguez on HBO and Terry Anderson on Eurosport, all the while building his brand – and demand for a Holyfield fight.

[springboard type=”video” id=”1126229″ player=”ring003″ width=”648″ height=”511″ ]

By the time Foreman met “The Real Deal” in April 1991 the fight was a bona fide event fated to be, for a time, boxing’s highest grossing match. While the 42-year-old Foreman lost on points he did so with honor. He absorbed Holyfield’s best – in round seven he tasted nearly two dozen unanswered bombs – and replied with a grit that dignified his attempt. For some, this moral victory might have been a cue to bow out gracefully. For this man of God, however, moral victories weren’t enough. Only a win over the reigning champion would suffice.

The signs weren’t encouraging. Foreman’s horribly swollen face while out-pointing Alex Stewart prompted many to declare “enough is enough” and his slow-motion loss against WBO titlist Tommy Morrison amplified the calls for retirement.

Foreman thought seriously about it when he heard Holyfield reveal his two-year-plan: Beat mandatory challenger Michael Moorer, unify the titles against Lennox Lewis and conclude with a megamatch against Tyson.

“Big George’s” hopes surged when, as TVKO’s color commentator, he saw Holyfield lose his belts to Moorer. Striking while the iron was hot, promoter Bob Arum contacted Moorer’s representatives about a fight with Foreman, who, despite his defeats to Holyfield and Morrison, still carried immense name recognition. The WBA refused to sanction the fight and threatened to strip Moorer of its title, prompting Moorer to withdraw. Undeterred, Foreman sued the WBA and the judge, knowing the WBA often circumvented its regulations to suit its purposes, ruled for Foreman. That verdict resurrected the fight as well as Foreman’s opportunity to cap his quest.

“I get up in the morning, I want it,” Foreman said shortly before meeting Moorer. “I go to bed at night, I dream about it. To fight for the world heavyweight title is very important to me but it’s a private quest.”

*

Like the version of Foreman that reigned in the 1970s Moorer was a moody, brooding champion who loved nothing more than to inflict pain.

“I crave violence of any kind,” Moorer said in the May 1989 issue of KO. “I want to break someone’s jaw. I want to see it shift, see how their mouth hangs open.”

“Michael is just a vicious guy by nature,” then-trainer Emanuel Steward opined. “He has that Mike Tyson mentality. There have been times when he’s been in the gym and he just screams ‘I’m going to take somebody’s head off.'”

At light heavyweight Moorer fired compact combinations that mirrored a young Joe Louis. All 22 of his 175-pound fights ended in KO victories, including 10 WBO title defenses. Weight-making, however, eventually wrecked Moorer’s 6-foot-2 frame. Before his December 1990 fight with Danny Stonewalker Moorer dried out to the point of near-unconsciousness and though he won every round before registering an eighth-round stoppage Moorer had had enough. While Steward wanted Moorer to pursue unification fights with Virgil Hill and Prince Charles Williams, Moorer made the ambitious jump to heavyweight.

Happily for Moorer his power followed him up the scale as his KO streak grew to 26 before ending against Mike “The Giant” White. Moorer’s viciousness, however, ran hot-and-cold at the more comfortable weight. His ferocity shone brightly against Bert Cooper and during his rematch against Frankie Swindell but was subdued in out-pointing Bonecrusher Smith and Mike Evans. To address this, Teddy Atlas, who, like his mentor Cus D’Amato, stressed boxing’s mental dimensions, was hired as Moorer’s trainer. Atlas’ fiery speeches during the Holyfield fight vaulted him into prominence but at his core he was a deeply introspective strategist. He, more than most, recognized the potential of a Foreman upset – under certain circumstances. Specifically, that scenario would be a stationary Moorer allowing Foreman enough time to line up one right to the jaw.

“I’m not worried about Michael Moorer losing to George Foreman,” Atlas told The Philadelphia News’ Bernard Fernandez. “My biggest concern is that Michael Moorer does not lose to Michael Moorer.”

In Atlas’ eyes the bad signs began to pile up. Foreman scaled a ready 250, six pounds lighter than the Morrison fight, while Moorer’s 222 was eight pounds heavier than the Holyfield bout. Moreover, the sight of Foreman power-walking into the arena to Sam Cooke’s “If I Had a Hammer” jolted Atlas.

“As if that weren’t bad enough, he was wearing the same boxing trunks that he had worn against Ali in Zaire in 1974,” Atlas wrote in his autobiography. “I had to use all my discipline to push away negative thoughts when I saw that because what those trunks indicated to me was that here was a man who was facing down his past. He wasn’t running from his ghosts. He was confronting them head-on. I was scared. A guy who was able to face the truth that way was a dangerous guy.”

Atlas also had qualms about his blueprint of bringing the fight to Foreman but chose to stick with it because he felt pulling back the reins would have undone the psychological progress Moorer made against Holyfield.

Statistically Moorer held every advantage. At 26, he was 19 years younger and he was far faster. He was undefeated (35-0, 30 KOs) and he was only the second southpaw Foreman had faced as a pro (Bobby Crabtree was the other). Finally, Foreman hadn’t fought in 17 months while Moorer’s six-and-a-half month hiatus, still the longest of his career, was more manageable. The smart money was with Moorer but the odds were minimized by the legions who bet with their hearts.

The sentimentalists had one substantive argument: Some fights are won not by the one who can give it better but by the one who can take it better. While “Big George” absorbed dozens of clean punches from Holyfield without falling Moorer was dropped by Holyfield’s compact hook. The Holyfield fall was just one of four knockdowns Moorer had incurred to date; the other three occurred in back-to-back fights against common opponents Martin (round three) and Cooper (rounds one and three). If Foreman could land one full-powered punch on that chin, they thought, the world might witness history.

The first round was a jabbing contest in which both got in their licks. Within two minutes, however, Moorer’s jabs had raised a mouse under Foreman’s left eye. Foreman managed to land several rights but the round was still Moorer’s.

“The hardest part of the fight is over,” Atlas said between rounds. “It’s not make-believe anymore, he’s just a guy. Our sparring partners were better. Now listen: What he’s trying to do is set you up for one shot. He’s trying to sneak-punch you. I don’t want you standing at the same range. You gotta step out of range every once in a while; he’s got you slowly standing in his range where he can find you with the right hand. Be very alert. Change your distance and move to the side.”

Curiously moving to his right – directly into the path of Foreman’s power – Moorer was able to pop the right jab and mix in spearing lefts while Foreman patiently pursued. Foreman’s singular connects brought cheers but mostly the spectators sat in tense anticipation. The difference in speed was graphic but as Moorer piled up points the prospect of Foreman’s power continued to lurk.

In round three a double right hook forced Foreman to take a step back but the tough Texan shook it off and resumed firing rights at every opportunity. A strong combination capped off a dominant Moorer round. According to CompuBox, Moorer landed 40 of 72 (56%) to Foreman’s 20 of 57 (35%).

“The last part of the round was the first time you didn’t let him bulls**t you,” Atlas said. “You kept it at your pace and what happened? It was the way we expected, right? You started finding him and you started getting to him. If he was in camp, he couldn’t last.”

But last Foreman did. Moorer scored nearly at will in the fourth but the hulking challenger remained unmoved, both in body and in spirit. Plus, he landed just enough rights down the middle and clubbing hooks to the side of the head to keep things interesting. The pace picked up considerably in the fifth and surprisingly it was Moorer whose mouth began to hang open. Still, Moorer maintained the volume and Foreman couldn’t keep up.

In the sixth the crowd tried to lift Foreman’s spirits by chanting “George! George! George!” and the challenger responded by driving in short uppercuts that set up head-snapping crosses. It was, by far, Foreman’s best round to date Unfortunately for “Big George,” who landed 63% of his total punches, Moorer landed 73% of his.

Moorer jabbed and hooked well in the seventh while a markedly slower Foreman struggled to pull the trigger. As the round ended HBO’s Larry Merchant declared, “I think the myth of George’s power has been exposed by Michael Moorer so far. (Foreman) just doesn’t have the quickness to make the force of a knockout.”

Atlas, however, believed Moorer was the one who needed to pick it up.

“Remember what I told you in camp about an old car?” he asked. “This is an old car. (If) you’re letting him go slow he can make it down the road. You make him go faster, it’s going to start to break down. Let’s start making him go faster now.”

Foreman, however, was starting to find the key. A solid right shook Moorer 45 seconds into the eighth and he followed with a hurtful combination. Moorer continued to connect but Foreman now had reason to hope.

For the audience at least, round nine gave them reason to doubt. Moorer threw 79 punches and landed 43 while Foreman was a mere 15 of 35. As round 10 began the near-capacity throng buzzed quietly, realizing time was running out for their hero.

Forty-five seconds into the 10th, Foreman found the groove with boxing’s most basic combination – the one-two. One jolted Moorer’s head and another connected 11 seconds later. After tasting several Moorer jabs, Foreman landed yet another right to the jaw and a pair of right-lefts. A clearly tired Foreman threw himself off balance whenever he missed but he continued his chase because he appeared to sense something significant was happening.

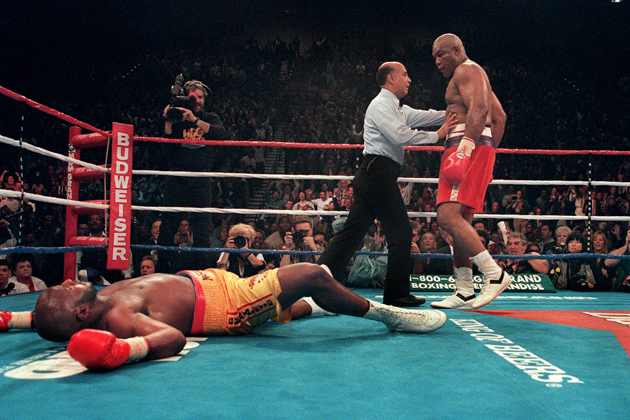

With 1:13 remaining Foreman landed a pinpoint left-right to the chin. Two seconds later, Foreman delivered the coup de grace, a sharp jab-cross to the button that fogged Moorer’s eyes, collapsed his legs and left him flat on his back.

Photo by John Gurzinski / AFP

“Down goes Moorer on a right hand!” HBO’s Jim Lampley yelled, matching the excitement reverberating throughout the MGM Grand. “An unbelievably close-in right hand shot….it happened! IT HAPPENED!”

“I can’t believe it,” Clancy said after Foreman knelt in prayer in the neutral corner. “He sure fooled me – and Michael Moorer.”

“You know, this was a 2-to-1 fight but in my mind it was a gazillion-to-one that George Foreman could ever win the heavyweight championship again,” Merchant said. “This is a really remarkable achievement and it has to stand on its own. We’re in a show-and-tell medium, and show does it all.”

The win enabled Foreman to achieve history on several fronts. First, the 20 years between championship reigns became – and remains – the longest gap in ring annals. Second, at 45 years 310 days he shattered Jersey Joe Walcott’s previous record for oldest heavyweight championship winner by more than eight years. Finally, he passed onetime adviser Archie Moore’s mark of 44 years 190 days as the oldest man ever to win a major title fight.

Most importantly, Foreman had achieved peace of mind. The embarrassment of the Ali fight was overwritten by the happiness of the Moorer knockout.

“I’ve exorcized the ghost once and forever,” Foreman said. “I’m heavyweight champion of the world and I’m happy about that.”

So was the rest of the world. For those lucky enough to experience the excitement that occurred 20 years ago today, the power of that moment will be ingrained in their memories for the rest of their days.

*

Lee Groves is a boxing writer and historian based in Friendly, W.Va. He is a full member of the BWAA, from which he has won 12 writing awards, including nine in the last four years and two first-place awards since 2011. He has been an elector for the International Boxing Hall of Fame since 2001 and is also a writer, researcher and punch-counter for CompuBox, Inc. He is the author of “Tales From the Vault: A Celebration of 100 Boxing Closet Classics. To order, please visit Amazon.com or e-mail the author at [email protected] to arrange for autographed copies.