‘A Cuban Boxer’s Journey’: Author discusses new Guillermo Rigondeaux book

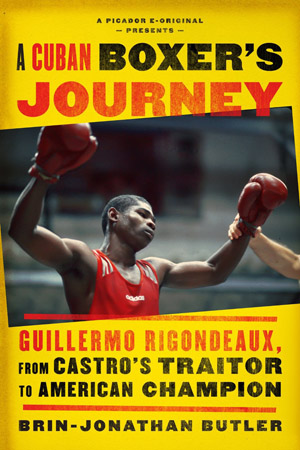

Barely out of his teens, author Brin-Jonathan Butler crossed the Florida straits in 2000 to find one of Cuba’s more obscure tourist attractions: a 103-year-old man purported to be Ernest Hemingway’s inspiration for The Old Man and the Sea. In 2007, Butler returned, this time in search of the island’s most famous outcast. The result is A Cuban Boxer’s Journey: Guillermo Rigondeaux, from Castro’s Traitor to American Champion (Picador, New York).

Barely out of his teens, author Brin-Jonathan Butler crossed the Florida straits in 2000 to find one of Cuba’s more obscure tourist attractions: a 103-year-old man purported to be Ernest Hemingway’s inspiration for The Old Man and the Sea. In 2007, Butler returned, this time in search of the island’s most famous outcast. The result is A Cuban Boxer’s Journey: Guillermo Rigondeaux, from Castro’s Traitor to American Champion (Picador, New York).

Prior to that year, Rigondeaux had been a national hero. He’d won two Olympic boxing gold medals and was expected to win two more, his extraordinary amateur career included 475 fights with only 12 losses, and he occupied a place in the Cuban pantheon alongside Teofilo Stevenson and Felix Savon. And, just like them, Rigondeaux was forbidden to leave and earn money as a pro.

He tried and failed to defect shortly before Butler’s arrival in 2007, then succeeded in 2009. In between, Rigondeaux was shunned by everyone else in his home country.

On U.S. soil with pedigree in hand, primed for worldwide stardom, Rigondeaux lived up to the hype – in a way. Just seven fights into his professional career, he won the interim WBA junior featherweight belt, and by his ninth bout the full-fledged version of the title was rattling around his skinny waist. He unified it with two others – WBO and RING – three fights later, in 2013. It was and it wasn’t a great achievement, because even though he’d befuddled pound-for-pound Pacquiao-in-waiting star Nonito Donaire for the win, his overly technical style proved to be a boo-magnet for fans, and his own promoter publicly declared him an anti-attraction. Welcome to America.

Such is the soporific power of Rigondeaux’s name, in fact, that some readers likely didn’t make it past the title of this article. For others, the fighter is a misunderstood prodigy, “a Mozart” as Butler puts it. Ample time is given to the subject of style in the book. But it is not the point.

A Cuban Boxer’s Journey is not a drawn-out fight report, nor is it an overbearing treatise on Cuba/U.S. relations, but it is an attempt to examine an isolated nation’s dilemmas through the ordeals of one isolated boxer. Butler was there to document Rigondeaux’s journey first-hand, he sat in Savon’s house to discuss what it’s like to turn down a fortune, and conducted Stevenson’s last interview for the price of $130 and a bottle of vodka. After a robbery in Ireland threatened the entire project, Butler gambled his savings on a first-round knockout at 20 to 1 odds. The dedication alone is something to behold. Throw in some some speedboats and near-riots and you’ve got a unique look at the consequences faced by human beings on both sides of boxing’s ugliest choice.

Below is a conversation with the author. The book can be found on Amazon here.

Brian Harty: Prior to 2007, what was life like for Rigondeaux in Cuba?

Brin-Jonathan Bulter: Well, he would’ve enjoyed all the acclaim and comforts of being the biggest star the boxing team had. He inherited the captaincy back in 2000 from [three-time gold medalist] Felix Savon who, in turn, had inherited his captaincy from [three-time gold medalist] Teofilo Stevenson. So Rigondeaux was the preeminent star on that team and, as such, he was given a house by Fidel, he was given a car – I heard it referred to as Cuba’s answer to a Bentley – which was a Mitsubishi Lancer, bright yellow, that more than anything he loved to just drive around Havana and everybody knew it was him.

BH: And what was his status like compared to Stevenson and Savon?

BJB: I think he was the biggest threat Cuba had to do what nobody had ever done before, which was to win four Olympic gold medals, and I think he’d done it a lot easier than Savon or Stevenson had done to win two. He was the same age as they were at the time they won their medals, so the plan was really for him to go to Beijing in 2008 and London in 2012.

BH: With that sort of life, why did he want to defect when the others had stayed?

BJB: I think it’s very simple. He felt, based on his ability and his place in Cuban society, he deserved a lot more rewards than he was given by the state. He couldn’t replace a refrigerator for his parents that he was pleading with the government to help him with. So he saw coming to America as a way to earn market rates on what his abilities determined.

BH: For the good of his family or for his own sake?

BJB: I think chiefly he felt he deserved more personally. I think he resented that in Cuba the only superstar that’s permitted, at least officially, is the system itself. I think not just for the financial rewards, but he wanted to be recognized as an individual – as an exceptional individual. It’s something that really was important to him. He said his biggest fear was ending up like the great champions who had come before him, who he said were given a few handshakes from Fidel and then ended up on a street corner telling people about their great achievements. Nobody outside of Cuba really cared, and I think he felt that was a real injustice. He saw himself as a world-class athlete, and, but for the fact of being born in Cuba, as someone who [could be] a very important athlete, and he was never going to be that if he stayed.

BH: You did track down and meet both Savon and Stevenson, as well as [two-time gold medalist] Hector Vinent, and in fact your interview with Stevenson turned out to be his last. Describe those meetings and the contrasting situations of those three men.

BJB: Castro banned professional sports on the island back in 1962, shortly after the revolution, and I think the most prominent athlete who emerged post-revolution was Teofilo Stevenson. Castro was always using his athletes as a way of symbolically defeating the United States, in the ring, and after these Cubans defeated Americans in the ring they were turning down exorbitant sums to leave the island. So, Stevenson won three Olympic gold medals, and each time the offers came he rejected them, and when I was seeking him out I was eager to see how they would treat somebody who was the most famous face on the island after Fidel. And he had been given a modest home in a relatively well-to-do neighborhood by Cuban standards, but suburban by American standards. I mean, a high-class neighborhood in Cuba is one where there’s paint that is reasonably fresh. He had a mid-1990s Toyota Tercel in his driveway that he didn’t have money to put gas in. He had a flat tire that he didn’t have money to replace. But he had the only swimming pool in the neighborhood. He came from quite a lot of poverty in his childhood so I think he was very appreciative of both the house and the neighborhood, and his standing in Cuba, which was something of a hero. These are things he was very proud of, but he was destitute. And the only reason he was willing to talk to an outsider was that, certainly, he knew there was some money that was going to change hands and he was not going to give that money to the government. He needed it. So that was difficult to see, the condition he was in, someone who could’ve been living like a king over in a mansion in Miami, but I got no sense he regretted the decision he had made. I just had a sense there was a real cost to it, and I wanted to explore that cost, and it wasn’t something he offered in the words he spoke but certainly in the way he spoke them, and just his own physical state betrayed a lot of the cost of saying no to all that money and the comforts it would have brought. He just seemed defiant about why anyone would leave. He had contempt for anyone who would accept the money.

BH: And how did that compare to Savon and Vinent when you met them?

BJB: Savon won his first medal in the ’92 Olympics, as did Hector Vinent. That year was, in most Cubans’ memories, one of the hardest times since the revolution – widespread blackouts, starvation, just shortages everywhere – so the incentive to leave then was enormous, and far more tempting than it was during Stevenson’s time in the 1970s when, because of being subsidized by Russia, Cubans lived rather well. But Savon ÔǪ I didn’t sense any regret or bitterness or any of that. There didn’t seem a big cost to the decision he made. He was like, ‘I never dreamed of having a 1975 stereo system! This is amaaaazing! And it’s amazing to have a three-bedrrom house in the middle of nowhere next to the airport! Isn’t this incredible? Aren’t you amazed to be here?’ And it’s like, well, it is kind of great. You know, I live in a 400 sq. ft. apartment, so yeah – it’s not that bad. It’s not great. It’s not Mike Tyson’s house, but I’d rather be you than Mike Tyson, sure.

BH: And yet just like Stevenson you had to pay him under the table for the interview and he cut you off when the clock ran out.

BJB: Absolutely. And last I heard is that he has an agent actually representing him for people who want to talk to him now, who gets a percentage. (laughs) So he’s very much playing the game as it’s done over here, at least on Cuban terms. Whereas Hector Vinent described, boxing internationally, that he couldn’t fight anywhere without people breaking open suitcases full of money or tossing him crumpled pieces of paper that had figures marked down just to discuss the prospect of him leaving. And then his teammate, Joel Casamayor, did defect in Atlanta and Vinent was the one who paid the consequences for fear that he would follow suit, or that he had conspired to also leave, which was untrue. Vinent said he couldn’t separate from his family no matter how much money was offered. But there certainly was an enormous amount of temptation that he confessed to having. He described the United States as like a woman who’s in love with you who you just have to spend your entire life ignoring, which I thought was a very poignant, wonderful metaphor.

Continue reading…