Matthew Saad Muhammad always brought his ‘A’ game

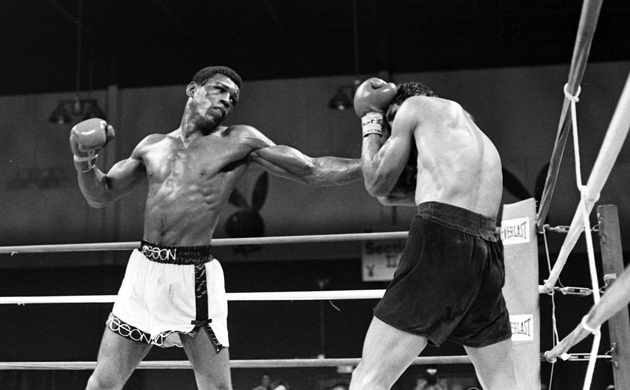

Matthew Saad Muhammad (left) lands a sweeping left against Yaqui Lopez during their 15-round battle at the Great Gorge Playboy Club on July 13, 1980 in McAfee, New Jersey. Saad Muhammad retained his WBC light heavyweight title in THE RING’s Fight of the Year. Photo by The Ring Magazine/Getty Images

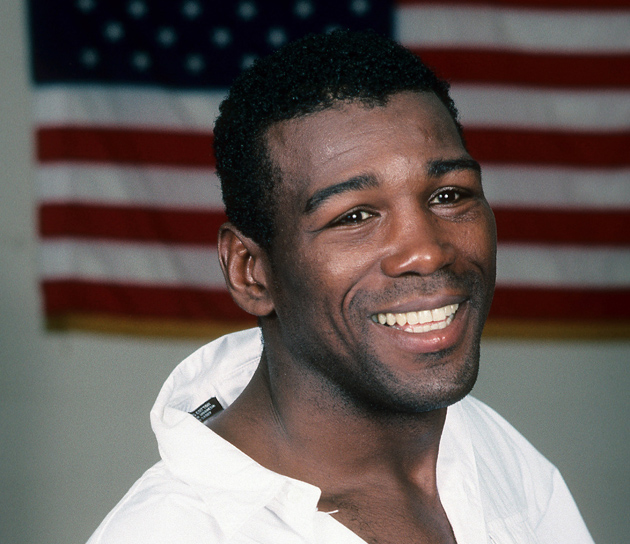

Athletes often speak about the necessity of bringing their “A” game for the big fight or the big game. Matthew Saad Muhammad, the former WBC light heavyweight champion who was 59 when he died early Sunday morning in a Philadelphia hospital of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, more commonly known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, always brought his “A” game.

The “A” stood for action. There might be boxers who generated as much heat and as frequently as did Saad Muhammad, but if there were, it doesn’t take long to call the roll. Saad’s approach to boxing was all-action, all the time. He was Jake LaMotta after Jake LaMotta, Arturo Gatti before Arturo Gatti. Then again, maybe it’s wrong to even try to compare him to anyone else. Saad was a true original, a whirling-dervish force of nature whose refusal to take a backward step regardless of the punishment he was receiving stamped his every ring appearance as must-see. It’s little wonder he was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1998, his first year of eligibility.

Most exciting prizefight of all time? A crowded field of candidates for that designation, to be sure, but certain to draw votes from anyone who saw it would have to be the first matchup of Saad and Marvin Johnson on July 26, 1977, at the Spectrum in Saad’s hometown of Philadelphia. The toe-to-toe exchanges began early in the first round and continued until the 12th and final round, when Saad finally put away the equally determined Johnson on a blood-splattered technical knockout.

“I would say from the summer of ’77 until the fall of ’81 he was probably the greatest action fighter in the history of his division, and probably one of the top 10 action fighters ever,” said longtime Philadelphia boxing promoter J Russell Peltz, who was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 2004.

“From the time he knocked out Marvin Johnson in their first fight, which is still the greatest fight I ever saw, through the Jerry Martin fight in September of ’81, he was the most entertaining fighter you could imagine. And he did that in what probably was the strongest era in the history of the light heavyweight division. In addition to Saad and Marvin Johnson, you had Michael Spinks, Eddie Mustafa Muhammad, Yaqui Lopez, (Billy) `Dynamite’ Douglas, Richie Kates, Jesse Burnett, Ronnie Bennett, Mike Rossman, Victor Galindez, James Scott, John Conteh and Jerry Martin. I mean, you could name 20 guys who could probably clean house today.”

In January of 1998, shortly after hearing of his election to the IBHOF and impending induction later in the year, Saad addressed the take-no-prisoners style that had him such a mythic figure.

“I was in a lot of wars,” he said. “People would see me get hit and not know how I could take the kind of shots that I took. Sometimes I don’t even know how I did it myself. It’s like God told me to get off that canvas and keep going.”

And his best-in-show performance? Saad also figured it was the epic slugfest with Johnson, whom he again defeated, on an eighth-round stoppage, for the WBC 175-pound title on April 22, 1979, in Johnson’s hometown of Indianapolis.

“The (first) fight with Marvin Johnson had to be the fight of the century,” Saad said. “It was like rock ’em, sock ’em robots all the way. Same thing with my fight with Yaqui Lopez and the second fight with John Conteh. It was fights like that that made me who I am.”

Saad’s final record – 49-16-3, with 35 knockouts – might not appear overly impressive at first glance, but it is deceiving. He was 8-13-1 in his last 21 ring appearances, when the wear and tear to his body had reduced him to a shell of his former greatness.

“Toward the end I started losing my power,” he conceded. “You can’t fight the way I did unless you got something to back it up. I couldn’t back it up any more.”

But when he could back it up, Saad did so in an unforgettable way. And he knew it.

“When I was at my best, I think I would have had a chance to beat any light heavyweight because of the way I fought,” he said. “I got in trouble sometimes, but I always came right back at you.”

Poor money-management skills and a profligate lifestyle during his prime had caused Saad to lose the entire $4 million he had earned as a fighter, and several years ago he was so destitute he had to swallow his pride and walk into a homeless shelter in Philadelphia. But to his friends in boxing, he always remained a onetime terror in the ring and among the nicest people in the sport outside of it.

“He became one of my best friends, like, the day after I fought him,” said former WBA light heavyweight champion Eddie Mustafa Muhammad. “You never saw Saad without a smile on his face, even when things didn’t go his way.”

[springboard type=”video” id=”936073″ player=”ring003″ width=”648″ height=”511″ ]